Multi-Layered Defenses

Louisiana is an example of a very low-profile coastal area characterized by relatively newly deposited delta sediment (less than 10 thousand years) of the Mississippi River delta. Land loss has been ongoing at a rapid pace over the past century, peaking in the late 20th century, and is currently occurring at a rate of approximately 10 – 20 square miles per year. The communities in coastal Louisiana are all at risk of storm surge inundation, to varying degrees. We have already looked at New Orleans in detail and seen that it has a system of flood defenses recently upgraded after Hurricane Katrina. Many smaller communities that are located close to the Gulf of Mexico have no protection from federally funded flood protection. Many have levees built and maintained at a parish level. New federally-funded hurricane protection levees, such as the Morganza to the Gulf levee system are planned to protect towns such as Houma and Thibodaux. This approximately 100-mile-long levee that averages 6 meters (20 ft) in height is also described in the Times-Picayune article. But some small communities such as Cocodrie and Isle De Jean Charles will not be within the footprint of this levee. It is not feasible in terms of available funding and engineering options to protect some communities. This presents a dilemma for many communities.

Louisiana's Coastal Master Plan and Multi-layered Protection

Levees are not the only form of protection for coastal communities. Louisiana’s Coastal Master Plan incorporates the concept of a multi-layered defense system that includes maximizing the flood mitigation potential of barrier islands, marsh, and natural ridge restoration projects, (many of which involve pumping sediment from a designated location, often from the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico), as well as the use of fresh water and sediment diversions from the Mississippi River to build new land.

Recommended Reading

Learn more about this complex plan by visiting Louisiana’s 2023 Coastal Master Plan. At this site, you can read an overview of the plan, its objectives, its progress to date, and the principles upon which it is founded.

What is Multi-layered Protection?

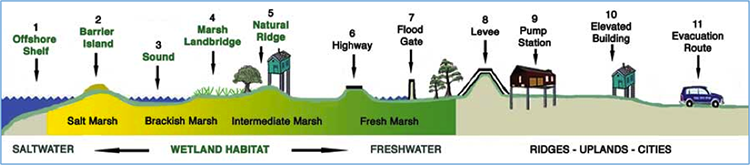

A clear explanation of the concept of Multi-layered protection is presented by the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation outlined at Multiple Lines of Defense Strategy. This conceptual approach identifies eleven “lines of defense”, which work in concert to ameliorate the effects of a storm surge by creating friction and reducing storm surge and wave height as it moves inland across the low-lying delta land. This plan was published and incorporated into Louisiana's Coastal Master Plan in the years after Hurricane Katrina. The eleven layers of protection are shown in the diagram below:

- Offshore shelf

- Barrier islands

- Sound

- Marsh land bridge

- Natural ridge

- Highway

- Flood gate

- Levee

- Pump station

- Elevated buildings

- Evacuation route

Video: FPA East Virtual Tour (16:06)

This is a virtual tour of the 17th St Canal Pump Station and the Surge Barrier in New Orleans. The first part focuses on Hurricane Katrina's destruction, while the second part showcases the flood protection system: Hurricane Storm Damage and Risk Reduction System (HSDRRS).

[DIAL TONE]

PRESENTER 1: Devastating damage expected. Hurricane Katrina, a most powerful hurricane with unprecedented strength rivaling the intensity of Hurricane Camille in 1969. Most of the area will be uninhabitable for weeks, perhaps longer. At least 1/2 of well-constructed homes will have roof and wall failure. All [INAUDIBLE] leaving those homes severely damaged or destroyed. The majority of industrial buildings will become nonfunctional.

Partial to complete wall and roof failure is expected. All wood-frame low-rising apartment buildings will be destroyed. Concrete block low-rise apartments will sustain major damage, including some wall and roof failure.

High-rise office and apartment buildings will sway dangerously, a few to the point of total collapse. All windows will blow out. Airborne debris will be widespread and may include items such as household appliances and even light vehicles.

Sport utility vehicles and light trucks will be moved. The blown debris will create additional destruction. Persons, pets, and livestock exposed to the winds will face certain death if struck. Power outages will last for weeks as most power down and transformers destroyed.

Water shortages will make human suffering incredible by modern standards. The vast majority of native trees will be snapped or uprooted. Only the heartiest will remain standing but be totally de-foliated.

Few crops will remain. Livestock left exposed to the winds will be carried. A [INAUDIBLE] hurricane wind warning is issued when sustained winds near hurricane force [INAUDIBLE] hurricane force are certain within the next 12 to 24 hours. Once tropical storm and hurricane-force [INAUDIBLE], do not venture outside.

[ALARM SOUNDING]

PRESENTER 2: On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina made landfall in Louisiana, forever reshaping the landscape and the lives of those in its path. In addition to a path of destruction, the storm left people of New Orleans with uncertainty. Could New Orleans rebuild? And if so, how would the Crescent City survive if another storm similar to Katrina's strength was to strike?

With that question in mind, the federal government and the US Army Corps of Engineers went to work planning, designing and building one of the most ambitious flood protection systems in the world. The result is what you see today. The levees, barriers, and pumps that make up the Hurricane Storm Damage Risk Reduction System, known as HSDRRS.

Today, this system is operated and maintained by the team at the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority East.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Welcome to the pump station at the 17th Street Canal. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, the US Army Corps of Engineers constructed interim closures with temporary pumps at the mouths of the 17th Street, Orleans Avenue, and London Avenue outfall canals. The goal here was to prevent storm surge from Lake Pontchartrain from entering the canals during a tropical event, thereby reducing the risk of a failure along the canals.

The Corps' intent was to follow this temporary measure with the construction of a permanent, highly-automated, more sustainable solution. Soon we'll take an in-depth look at the more permanent solution. Let's begin our tour.

To your right, you will see the hydraulic gates that, when closed, cut off the lake from the canal. These gates are a critical part of the system. The brick building in front of you houses the pumps. We will head in there shortly. But first, let's head around to the back of the building.

You might be wondering what is significant about this side of the building. Well, for starters that is the 17th Street Canal in front of you. During a tropical event, any time the city pumps drainage water into the canal, we, in turn, pump the canal water into the lake. The goal is to prevent levee failure by reducing the stress on the canal walls.

The other thing you will notice is the metal structures coming up from the canal and towering over you. That is part of the mechanical screen and, when turned on, it will filter out debris from the water entering the pump station. Large screens catch the debris and then travel up the large metal tracks you see before you.

As they round the top, the debris falls onto the concrete pad that you're standing on. All right, it's hot out here. Let's head inside and get out of the sun. The building that we are now in houses the pumps at the end of the 17th Street Canal.

The giant machines that surround you are the pumps that help keep New Orleans safe, thus ensuring when the sewage and water board pumps are running the flow of water is one-directional, moving from the canal into the lake. Our two smallest pumps, which are all the way down on your left, can move 900 cubic feet of water a second, while our more numerous larger pumps can move double that-- 1,800 cubic feet of water in a single second.

To fully grasp how large these pumps are, notice how small Maintenance Mike looks when standing next to one. Let's move closer so you can take a look around some more. In order to protect New Orleans from flooding during a Hurricane, the pumps themselves need to be protected. This building has been designed to withstand sustained winds of 155 miles per hour and gusts up to 200 miles per hour.

From up here, you can get a better understanding of just how large these pumps truly are. Hang here for a bit and spend some time taking in the sights and sounds. It's OK to feel a little overwhelmed. It's quite impressive.

Now let's head down to the basement. Welcome to the basement of the pump station. Feel free to look around. And we'll start the tour back up in a moment.

Down here, we are standing 25 feet below the canalside water level. If you know anything about New Orleans, you know that basements are, well, rare. Each of these pipes is over 9 feet in diameter.

You'll notice Maintenance Mike taking his time inspecting the nuts and bolts holding these intake pipes in place. Each nut is striped with a yellow line so that we can easily tell over the course of time if they have come loose. When the yellow stripe on the nut lines up with the stripe on the bolt, we know they are tight and safe.

Interestingly enough, the water is not just pumped through the facility. But it is actually pumped from the bottom of the canal, up these pipes, and out through the lake side of the building. While the water is discharged below the surface, it has enough force to create a noticeably large wave.

So what does it take to move this much water? A whole lot of power. Welcome to the generator bay. Here you will find 15 2.6 megawatt generators. Take a look around for a bit.

When it comes to protecting the city of New Orleans from flooding, redundancy is everything. Each pump has two of these generators dedicated to it. In addition to that, this facility has generators and an on-site fuel storage facility allowing for full operation and off-grid protection.

The first thing many people think of when it comes to flood protection are the giant pumps that we just saw. However, those pumps only remove water from the city. What prevents water from entering New Orleans? Hold on tight.

Welcome to the IHNC Lake Borgne Surge Barrier. Consisting of over 3,000 piles, including 1,271 concrete cylinder piles that measure 66 inches in diameter and are driven to a depth of 130 feet into the ground, this is one serious barrier. So how does this all work?

Woo, back on solid ground. Directly in front of you is the main sector gate. When closed, you can walk across the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway, which is a major artery of marine commerce from Florida to Texas. Millions of dollars of shipments travel through this waterway on a daily basis.

Later on, we will take a look at the gate closing process. But for now, let's continue our tour. Further along is the Bayou Bienvenu Vertical Lift Gate and Bridge that help connect this nearly two-mile-long structure.

In fact, authorized vehicles are able to drive across for inspection and maintenance. Although it can be hard to see from here, the barge gate is exactly what it sounds like. It's a large barge that can be swung on in front of the barrier opening and then sunk to seal the opening off.

To your right and somewhat behind you is the primary control room. This is where the gate can be monitored and where the controls to open and close the gate are located. Take a minute to look around.

All right, ready to move on? Let's explore. Out here you can get a better view of the gate as well as see beyond the gate. Additionally, you will notice the building across the way. If you think this looks similar to the control room you saw earlier, you'd be right. That building is actually a secondary control room, allowing for the gate to be managed from both sides of the waterway.

Before we dive deeper into the gates, let's take a look at the surge barrier itself. As you look around, you'll notice on your right the levee portion of the flood protection system. While the pumps remove water from the city and the barrier closes off the flow of water, the levee helps protect against the storm surge typically associated with a major weather event. Let's move in a little closer to the levee.

Maintenance Mike is going to help us out now with a little demonstration. If you look slightly to your left, you'll see Mike standing next to the old levees which were part of the original flood protection system. These levees originally protected New Orleans against storm surges measuring up to 16 feet in elevation.

When standing next to the top of one, Mike is able to clearly see over it. These levees did the best they could. But to give you an idea of how challenging it was to prevent, the storm surge created by Hurricane Katrina was over 9 feet higher than these levees, topping out around an unprecedented 25 feet high. Now, Mike has moved across to the levees that are part of the new flood protection system.

As you can see, these are significantly higher than the old ones. In fact, at the highest point, the new levees are double the height of the old ones, topping out at 32 feet tall. Ready to move on?

Let's head back up to the gate and see if they are ready to start the closing process. Here we are in the control room, where our crew is about to get things started. Let's say a quick thanks to Patrick Brown for operating the gate for us today.

Now, let's head back outside to check out the action. Wow. Look at those gates close.

If you think they aren't moving, that's certainly understandable, as they do take over 15 minutes to move into place. But don't worry. You won't have to stand here in the heat for 15 minutes. Let's speed things up a bit.

Much better. All right, we're coming to the end of our tour. Before we leave, take a moment or two and look around some more.

We're back at the pump station and out of the sun. Thank you for joining us on the tour today. If you have any questions about something you saw, please do not hesitate to reach out to the New Orleans Flood Protection Authority East. Have a good one.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Learning Check Point

Please take a few moments to think about what you just learned then answer the following questions to test your knowledge.