Detecting Tsunamis: The US Tsunami Warning Center

Video: NOAA Tsunami Forecasting (2:33)

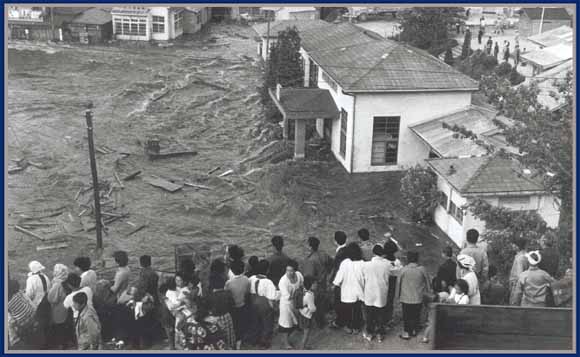

Today, in partnership with the USGS and NOAA, the US Tsunami Warning Center operates from Hawaii. The warning center was first created after WWII as a result of the 1946 Aleutian Island tsunami that originated between Alaska and Siberia. The tsunami produced incredibly destructive waves that traveled hundreds of miles to the south and resulted in the severe inundation of Hilo Bay, Hawaii and led to numerous deaths. Formerly initiated in 1949, the center expanded in the aftermath of the 1960 Chilean earthquake that not only destroyed many communities along the coast of Chile but also led to more destruction in Hawaii and even in Japan on the opposite side of the Pacific Ocean. With such severe long-distance impacts, it was clear that individual nations needed to collaborate in order to effectively save lives. As a result, efforts were initiated to coordinate monitoring around the Pacific, but even in 2004, the effectiveness of the center was limited as demonstrated by the 2004 Sumatran Tsunami that impacted much of the Indian Ocean. Although the earthquake and tsunami were detected from the Pacific, little could be done to monitor its progression in the Indian Ocean, and efforts were more or less futile in terms of issuing effective warnings to residents living around the Indian Ocean basin. As a result of that event, the center now coordinates with other tsunami warning centers in the U.S.and with the United Nations and similar agencies in several other countries including Japan, Australia, and others. These centers not only detect earthquake activity but also track the development and movement of tsunami waves as they travel across the world’s oceans. The main missions of these centers are to monitor and issue warnings, advisories, and watches to help reduce the loss of life associated with these events around the world.

The US Tsunami Warning Center is a great resource that provides details about specific events around the globe that are being monitored for tsunami generation. Australia and a few other countries maintain similar websites. It is worth spending a little bit of time exploring the types of tools and data that these agencies are collecting and monitoring to help keep the public as safe as possible from these types of catastrophes. It is, however, up to individuals and communities to be educated about tsunami risks and hazards and to act on the information provided in order to save lives. Individual communities are ultimately responsible for developing evacuation plans and limiting shoreline development, in especially susceptible areas. These topics will be explored in greater detail in later modules.

It’s clear that tsunamis pose an incredible threat to coastlines and societies around the world; but exactly what are tsunamis, how are they formed, and how do they interact with coastlines around the world? In order to answer these questions, we will explore two case studies. The first is the Sumatran Tsunami that occurred in December 2004, and the second is the 2011 Japanese Tsunami that devastated the island of Honshu, one of Japan’s main islands.