Streams

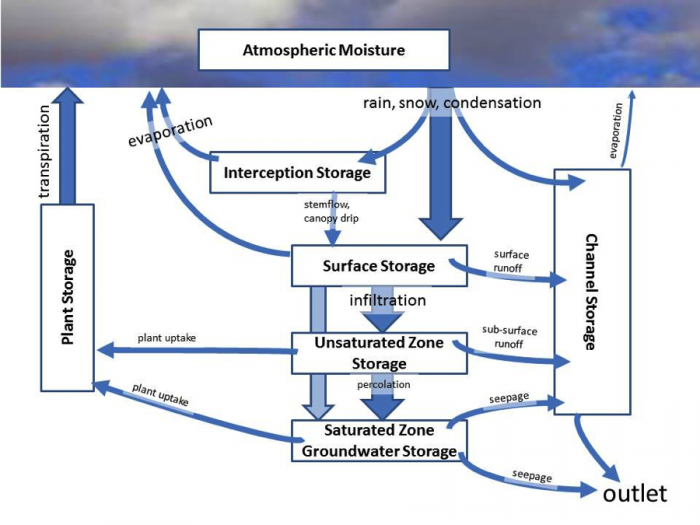

Streams are the most obvious way that water is moved through a watershed because we see them all over. But there are many other means by which water moves, as discussed in module 2. Figure 5 illustrates the various stocks (places were water is stored, even if only temporarily) and fluxes (mechanisms by which water moves) of water that may exist within any given watershed. For example, one raindrop might fall onto vegetation (called interception) and subsequently be evaporated back up into the atmosphere. Another raindrop might fall onto the soil surface and then runoff the surface into the stream channel or it might infiltrate down into the soil. Once in the soil, the water might further percolate down into the groundwater, where the soil or rock is saturated with water. Alternatively, once in the soil, the water might travel downhill within the soil and runoff into the stream or it might be taken up by vegetation and transpired back into the atmosphere. Estimating and predicting which, and to what extent, water travels through these pathways is an active field of hydrologic research and is also vitally important for environmental management and policymaking, as certain pathways may be more or less prone to filtering or polluting water along its journey to the place where you might want to use it for drinking, irrigating, fishing, swimming or the myriad other purposes for which we need water.