Lesson 9 - Government Intervention

Lesson 9 Overview

In this lesson, we continue our analysis of what happens when governments intervene in market processes. We will talk about how firms seek to enrich themselves, at the expense of the general welfare of society, by participating in a form of behavior called "rent-seeking." We will discuss why it is difficult to get this practice under control.

We will then look at some of the instruments that the government uses to try to modify market outcomes, namely, the setting of artificial controls on prices, and we will examine what the actual outcomes are, and why they are often different from the desired outcomes.

What will we learn?

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- define and explain what economic rents are;

- describe what we mean by "rent-seeking" behavior;

- explain why it is difficult to eliminate rent-seeking behavior;

- explain the idea of concentrated benefits and distributed costs;

- describe what a price cap is and graph it on a supply and demand diagram;

- describe what a price floor is and graph it on a supply and demand diagram;

- explain what we mean by the "hidden costs" of price controls, and the effects of hidden costs on producer and consumer surplus.

What is due for Lesson 9?

This lesson will take us one week to complete. Please refer to Canvas for specific time frames and due dates. There are a number of required activities in this lesson. The chart below provides an overview of those activities that must be submitted for this lesson. For assignment details, refer to the lesson page noted.

| Requirements | Submitting Your Work |

|---|---|

| Reading: Pages 72-78 (The Economics of Price Controls) in the text, and any required material linked to in the lesson. | Not submitted |

| Lesson 8 and 9 Quiz and Homework | Submitted in Canvas |

Rent-Seeking and Regulatory Capture

At this point, I want to introduce another term that has a different meaning to economists and the general public.

This term is "rent." To a layperson, rent is a term that describes payment made in exchange for temporary use of something, such as an apartment, a store, a car, or a DVD (think Netflix). However, to an economist, rent has a different meaning. An economic rent is defined as a return to a factor that is greater than the return required to incentivize the use of that factor. This is another way of describing an economic profit. Remember that an economic profit is a situation where a business generates profits that are larger than the risk-free rate plus an appropriate risk premium. In the case of economic rents, it means that some factor of production earns more than it "should" in equilibrium. In a market setting, this means that more of that factor will be employed, and competition will drive down the return to some equilibrium whereby zero economic profits are being made.

Rents, like economic profits, can be thought of as "free money" - and everybody likes free money.

One of the most common uses of the term is as part of the phrase "resource rents," which refers to the generation of positive economic profits from extracting minerals from the earth. For example, if the risk-adjusted cost of bringing oil out of the ground is \$20 per barrel, and a company is able to sell that oil for \$100 per barrel, then we say that they are collecting a resource rent of \$80 per barrel. In economic theory, because there is so much "free money" in extracting oil, then there should be a rush into the oil business, more oil produced, and the price falls to \$20. In reality, this tends not to happen quite so neatly - mostly because we have a cartel that supports the price of oil at high levels by limiting supply.

Another way to think of rent, in a somewhat pejorative sense, is to think of "unearned" profits. It can be difficult, in a positive sense, to say what exactly "unearned" means - that word is a bit like "fair" or "equitable," in the sense that it has some sort of normative connotation. However, think of the idea that rent means positive economic profits - more specifically, economic profits that are in some way shielded from market forces, and therefore, not subject to the sort of competition that tends to make them vanish. Remember that economics is dynamic by nature, and the forces of innovation and entrepreneurship send people in search of economic profits, so they will always exist. However, in a theoretically free market, as soon as economic profits appear, competition follows and the profits eventually vanish. This is not a market failure, merely the nature of competition. It is only a failure if the person earning the rents is able to stop the forces of competition from driving the rents down to zero. If this happens in a market, we have a monopoly (or, more commonly, an oligopoly) and we have a market failure. However, as I have said in the past, a monopoly can only persist in one of three situations:

- Natural monopoly (infinitely downward-sloping marginal cost curve)

- Control of all of a resource (such as deBeers and the diamond market,or, for a while, China and the rare earth minerals market)

- Government protection from competitive forces

Today, we will talk about the third of these factors - using government to protect and maintain rents. This is another source of government failure, once again referring to government failure as actions by government meant to address market failures, but which generally end up leaving worse outcomes than before the intervention. That is, government trying to fix a problem, but only making things worse.

Rent-Seeking

Rent-seeking is a way of transferring previously-existing wealth to oneself by something other than voluntary trade. It typically involves a transfer of wealth, not a creation of wealth like that which occurs in a market with voluntary trade driven by utility and profit maximization. Rent-seeking is the attempt to gain wealth without creating wealth. I will list a couple of examples of rent-seeking for illustration. Stealing is perhaps the “purest” example of rent-seeking. A thief takes what others earned without earning it. You may think that a thief invested time and energy in planning and executing the crime. However, it’s important to note that theft is simply a transfer of your stuff to me (should I steal from you), and that NOTHING IS CREATED. In a market transaction, buyers and sellers exchange goods for cash, and both sides benefit, so wealth is generated. In stealing, wealth is transferred, not generated. This is a rather extreme example, but it drives home the notion that rent-seeking is about transfers of wealth from one sector of society to another that are not the result of voluntary, mutually beneficial transactions, but instead are transfers of wealth that are effected by some sort of force. A mugger might hit you over the head and take your wallet, but when government takes wealth from one sector and transfers to another, there is the implied force that comes from the government having enforcement agents (police, prosecutors) to ensure that its wishes are carried out.

Now, putting aside the notion of simple theft, which is, in theory, opposed by governments, let us start to look at forms of rent-seeking that arise out of the seeking of favors from government. OK, so now we are talking about government power. Government has the power to pass laws, to write regulations, to collect taxes and to enforce the laws, regulations and taxes. Because members of government have lots of power, they have lots of favors to dole out, and it is the competition for these favors that forms the basis of rent-seeking. Firms are competing with each other, but instead of competing for customers by offering better products or better service at lower prices, they are competing for government favors. Instead of employing salesmen or engineers or factory workers, they are employing lawyers and lobbyists.

A lobbyist is a person who is employed by a company, or sometimes by an industry association, or by a union, or sometimes by a foreign country, who has the job of talking to politicians and bureaucrats, with the goal of having them pass laws and enact policies that are beneficial to the persons they are representing. The term "lobbyist" refers to the fact that these people used to wait "in the lobby" outside legislative bodies, waiting for the politicians to leave so that they could talk to them.

Any time or energy spent on gifts or bribes to government officials in exchange for government favors are rent-seeking. Let's say a firm is lobbying to obtain a lucrative contract, for, say, new airborne tankers - you know, the planes that refuel other warplanes in mid-flight. Once a firm has this contract, wealth is created by producing the tankers and selling them to the government. However, the resources the companies spend on acquiring the contract could have been productively used by the economy.

If you are not aware, the case of the new USAF tankers is a textbook example of rent-seeking behavior by suppliers: people have gone to jail, massive fines have been paid, a CEO lost his job, and the contract still remained unrewarded until 2010, after almost two decades of wrangling.

Recommended Reading

If you are interested, I direct you towards the Wikipedia entry on the KC-X, which presents a good summary.

Because government favors (subsidies, long-term contracts, exemptions, etc.) increase the wealth of the recipients of these favors, those eligible (or potentially eligible) will compete for the favors. We can say that rent-seeking is an equilibrium behavior - we expect firms to do it because they stand to derive meaningful benefits from it.

Firms have the incentive to waste resources on gifts for the official who will decide the winner of the contract because the firm will ultimately be better off. However, society is worse off because some resources were put to less than their best use — society’s opportunity costs have increased because a path of action that does not generate the maximum amount of utility for society was taken.

There are several ways to try to deal with the problem of rent-seeking. Out-and-out bribery is illegal (Federal employees cannot even accept free lunch at McDonalds), but making political donations, or paying for senators to take trips to Hawaii to "present a briefing" to them is not illegal. There are technocratic solutions, such as establishing objective (rather than subjective) criteria for large contracts. Also, the press will gladly expose any scandal they can uncover in light of these rules.

However, there is a basic problem that means that rent-seeking is not likely to go away anytime soon: politicians and bureaucrats have power, and as long as they have power, and exercise it, then people will compete with each other for the benefits derived from the exercise of this power. The only solution to this is to reduce the amount of power that resides in the hands of government - something that nobody in government has any incentive to do.

The Distribution of Costs and Benefits

If it is clear that rent-seeking is a practice that costs society great amounts of wealth by competing with each other for government favors, then why does the public not band together to stop it? Well, since this is an economics class, you can expect an economic answer: because stopping it is usually not beneficial for members of the public, or, to put it another way, the costs of stopping this sort of behavior is generally greater than the benefits of doing so that would accrue to any individual.

Suppose as a Penn State student (which I was, a few years ago), I am hurt by \$10/year by a new program to buy all tenured faculty members new office furniture. Furthermore, suppose it costs me \$50 (in cash and opportunities) – to organize with all affected people to fight the new program. Facing these alternatives, as a greedy individual, I am simply going to put up with the new program. It doesn't make economic sense for me to fight the program, even though fighting the program will probably be beneficial to students in aggregate.

This is the problem of concentrated benefits and distributed costs.

- You are less likely to protest a new industry tax-break if 300,000,000 people share the costs than if only 1,000 people share the costs.

- When the group of people paying are affected enough, they will organize, in the form of protests, lobbies, campaign contributions, or political activism (e.g., running for office).

Specifically, the costs of organizing have to be less than the cost of the program on the affected group. Finally, if I am rationally ignorant to the new cost (I don’t directly know about it, and don’t question a lower paycheck), I won’t even consider raising an objection. In general, we see costs being spread over broad groups, and benefits concentrated on narrow groups. As the result of all this, we see small, highly organized groups gaining benefits, while the rationally ignorant masses pay!

Examples

The sugar industry maintains high profits because of the existence of import quotas - they do not have to compete with foreign competition because of rules put in place by the government. The end result is that sugar is about twice as expensive in the US as in neighboring countries. Because of this, everybody in the US pays a few more dollars per year for their groceries, but about 800 sugar-growing businesses benefit by hundreds of millions of dollars. Because the sugar industry gets such great benefits, they spend a lot of time and effort on politicians to make sure the import quotas stay in place.

Another interesting example is the case of Breezewood, PA. If you ever drive down to DC from State College, you will find out that you cannot simply exit from the PA Turnpike directly to I-70, but instead you have to drive through the middle of this town. There have been several attempts to build bypasses around the town, but this would hurt the merchants of Breezewood, who have been able to successfully lobby to stop any attempts by PennDOT to build a bypass. Because of traffic backups through Breezewood, everybody pays a little bit, but a few people benefit greatly.

The government has passed laws requiring that a certain percentage of the gasoline sold in this country contain ethanol. This has created an industry that would not exist without the government mandate, because ethanol is generally more expensive than gasoline. This benefits farmers in the Midwest who grow the corn to make ethanol, and it helps the agribusiness companies that manufacture ethanol. But everybody else pays because ethanol has less energy per gallon than gasoline; so our fuel economy drops when we burn ethanol-containing gasoline. However, this is something most people are unaware of.

There are many other examples of rent-seeking. One of the most common ways of using government to eliminate competition is what is referred to as "regulatory capture." This is the case where regulators end up acting in ways that benefit the industries that they regulate. Many government agencies are generally created with the high-minded notion of protecting the public from rapacious behavior of corporations. However, these corporations can use the government agencies to protect themselves from competition, most frequently by encouraging a set of regulations that makes it very difficult for newcomers to enter an industry. They use the creation of regulations as a barrier to entry. For example, building electricity power lines is a relatively simple and affordable process, and a 100-mile transmission line can be built in perhaps half a year. However, it takes at least five years of navigating the regulatory process to get permission to build a new power line. Because it is so expensive and time-consuming, we probably have fewer than the ideal (economically efficient) number of power lines, and companies that own existing power lines are able to benefit from the high costs of congestion that exist on existing power lines.

Large companies are especially good at using environmental regulations to squeeze out smaller competitors, because there are economies of scale that can be put to use. A company with 20 refineries can comply with regulatory paperwork a lot more easily than a firm with one refinery, because the big company is more likely to employ specialists who do the work for all of their refineries. The small firm has to train somebody to do the regulatory filings even if it is not their primary job, or, more likely, to hire an outside consulting firm to deal with the red tape, which can be considerably more expensive than doing it yourself. For this reason, the number of small, independent refineries has shrunk greatly since 1980, and now only a few large companies dominate the industry.

Price Controls and Their Effects

Reading Assignment

Read pages 72-78 in the textbook, "The Economics of Price Controls" for this section.

When addressing market failure, one common perception of a problem is that the equilibrium price in a non-regulated market is not fair. Now, we have spent a lot of time in this course talking about "positive" and "normative" questions, and the notion of whether something is "fair" or not is manifestly a normative question. We do not have a reasonable and consistent definition of what "fairness" in a market situation is - ask a lot of people and you will get an answer that is something like "well, I know it when I see it." If some member of the political constituency is unhappy with prices, then they will often petition government to do something about these prices. One of the main tools available to a government to change the outcome of a market is a price control.

A price control comes in two flavors: a price ceiling, where the government mandates a maximum allowable price for a good, and a price floor, in which the government sets a minimum price, below which the price is not allowed to fall.

Price controls can be thought of as "binding" or "non-binding." A non-binding price control is not really an economic issue, since it does not affect the equilibrium price. If a price ceiling is set at a level that is higher than the market equilibrium, then it will not affect the price. Think of an example: suppose the borough of State College decides that it wants to make sure that no student is denied toothpaste, and decides that it will set a price ceiling of \$10 per tube on toothpaste. Well, almost all tubes of toothpaste cost a lot less than that - most are about \$3 or \$4 per tube. So setting a maximum price that is above the market equilibrium will not really affect the market equilibrium. The same can be said for price floors that are below the equilibrium price. If the state sets a minimum price of \$1.00 per gallon on gasoline, it is not going to have any effect at current price levels.

OK, so let's not worry too much about non-binding price controls. Let's restrict our thinking to ones that change the price that consumers see in the market. We'll start by talking about price ceilings, which are sometimes called price caps. Price caps are one way to address issues of market power. In situations where it is felt that the price is artificially high because of a lack of competition, one of the actions a government can take is to set a maximum price a monopolist can charge. Let's look at a couple of examples. One of the most frequently cited example is that of price caps on rental accommodations, the most famous case in the US being that of New York City. As the United States entered World War II in 1942, a crash program of ship-building was started in addition to other munitions and arms manufacturing. One of the places where many ships were built was the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The rapid increase in the demand for labor caused a lot of people to move to New York. These migrants needed places to live and soon filled up all of the available apartments in New York. Given that apartment buildings are capital, and cannot be built overnight in response to increased demand, when they filled up, landlords would be in a position of market power and would be able to charge higher and higher prices when every apartment came on the market or when a lease ended. In order to stop this from happening, as a wartime emergency measure, the City of New York instituted rent controls, setting maximum amounts on what a landlord could charge.

It should be noted that World War II ended in 1945. This was 75 years ago, but rent control persists in New York to this day. As an aside, the Federal Income Tax was originally intended to be an "emergency measure" to help pay for the costs of World War I. That war ended a little over a century ago, but the income tax is still with us. Perhaps this is a hint that we should be careful about granting politicians the power to adopt "emergency measures," as they have a habit of sticking around long after the emergency has ended.

You can imagine what these rent caps did. In a market, high prices serve as a signal to producers that demand has increased, and every businessman lives to find an unsatisfied demand. This is where the lure of positive economic profits lies. High prices act as a magnet to bring more supply to a market, and that extra supply competes with the existing supply to help drive prices down to an equilibrium. High rent prices are a signal, telling prospective builders where their product is most needed. This is what Adam Smith was talking about when he coined the metaphor "the invisible hand," guiding the behavior of consumers and producers.

Rent control removes the economic signal that buildings are in demand in New York. For this reason, providers of apartment houses have no incentive to build new apartments. So, we still have lots of workers flocking to the city, all the apartments are full, and nobody has an incentive to build new ones because the prices are controlled. This does nothing to alleviate the shortage of apartments. It just means that instead of apartments being rationed by price, they are rationed by some other method - maybe "first-come, first-served," but more likely some other method. These other methods are what we know as the "underground economy," which is otherwise referred to as a "black market".

In New York, rent control gave rise to a variety of practices, all of which were against the official rules. One was the practice of sub-letting. Say that you are lucky enough to have a rent-controlled (that is, cheap) apartment in Manhattan. You get married and start a family, and you decide you want to move out to the suburbs. Normally, a person in this situation would give up his apartment and buy a house in the burbs. However, it is profitable to officially keep your name on the lease, and instead allow somebody else to live in the apartment. Since apartments are scarce, people are willing to pay more than the market price. So maybe you can keep the lease, charge somebody \$2,000 to let them live in the building, and pay the landlord the rent-controlled rate, which might be \$600 per month. You have a big incentive to keep your name on the lease. Another practice is "key money," in which case landlords take "under-the-table" payments upfront to allow a person to move into a rent-controlled apartment. There are some other side-effects as well: because landlords can raise the price (by a small amount) when somebody vacates the apartment, they have an incentive to have people move in and out as often as possible, and they have no incentive to spend a lot of money on maintenance, as they are not interested in keeping tenants happy - a rather dysfunctional outcome that should never exist in an uncontrolled market.

Another side effect is that we still have a shortage of housing, and whenever there is a shortage, government gets called on to fix the problem. In this case, the City of New York built a lot of apartment buildings, which were commonly known as "housing projects" and quickly developed a reputation as being very unpleasant places to live. So, one government policy designed to alleviate market power led to lots of illegal and inefficient practices, lots of unhappy tenants, and the entry of the government into the housing market in a big way. It is fair to say that this is a case where a government trying to fix a problem has ended up making things a lot worse. Rent control is almost gone in New York, but has proved to be very difficult to phase out.

Anti-gouging rules are another example. In cases like this, sellers are barred from raising prices above some level that is thought to be "reasonable" in unusual circumstances that would normally allow them to raise prices. This topic often arises in the aftermath of natural disasters. Let's say, for example, that bridges to the Outer Banks of North Carolina get wiped out by a hurricane, and it is temporarily impossible to truck supplies to the islands. At the same time, power is out, so water cannot be pumped to homes. In this situation, there would be a large outward movement of the demand curve for water. At the same time, the replacement cost of the water (that is, the marginal cost of the replacement unit) would be very high, moving the supply curve up. Both of these effects should cause the price to increase significantly. When this happens, it is often decried as "greed" in the face of tragedy. In reality, raising the price of bottled water is the signal that tells other firms to do whatever they can to get water to the islands. If the price of a bottle goes up to \$10 or \$20, then some other supplier would hire helicopters or boats to make sure that they could sell water on the island. If the price is capped at, say \$3 per bottle due to anti-gouging rules, then no other company has an incentive to move water to the islands and the shortage persists longer than it otherwise would. Another example: in North Carolina, anti-gouging laws cap the price rises of gasoline when the governor activates the laws. After Hurricane Ike hit the refining belt in Southern Texas in 2008, there was an acute shortage of gasoline in the south. Several gas stations were fined for raising their prices too quickly, from \$2.50 to over \$4. Oddly enough, one station near the Orlando International Airport that always priced its gas at over \$4 per gallon, due to proximity to car rental lots, was not fined, even though their price was as high as the "gouger" stations.

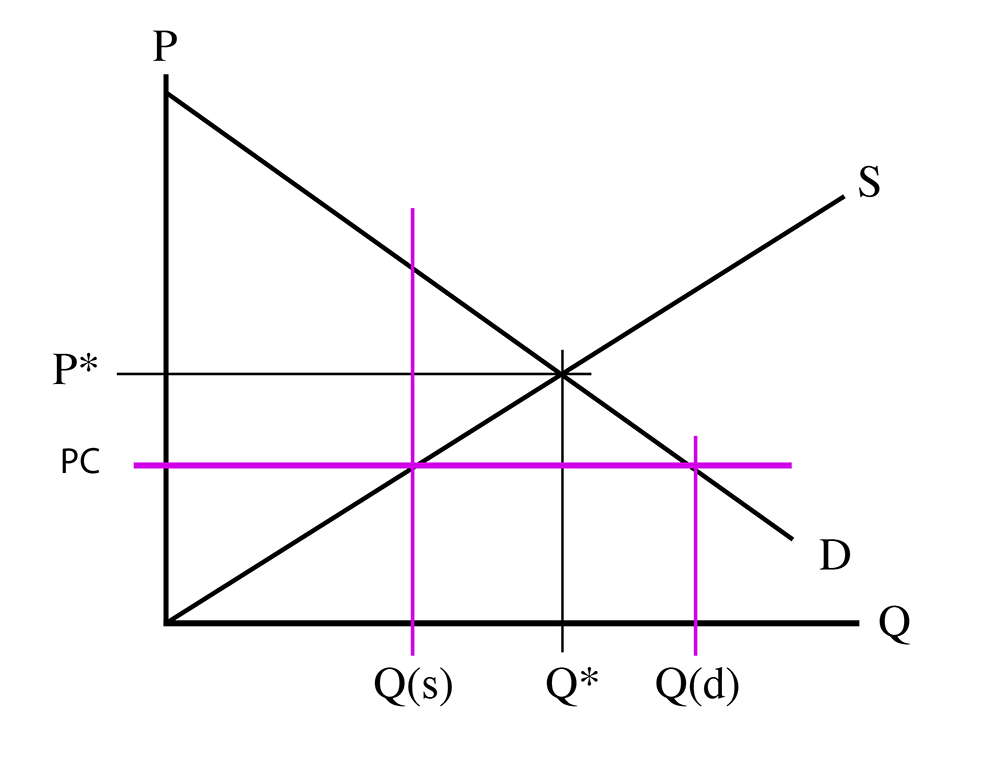

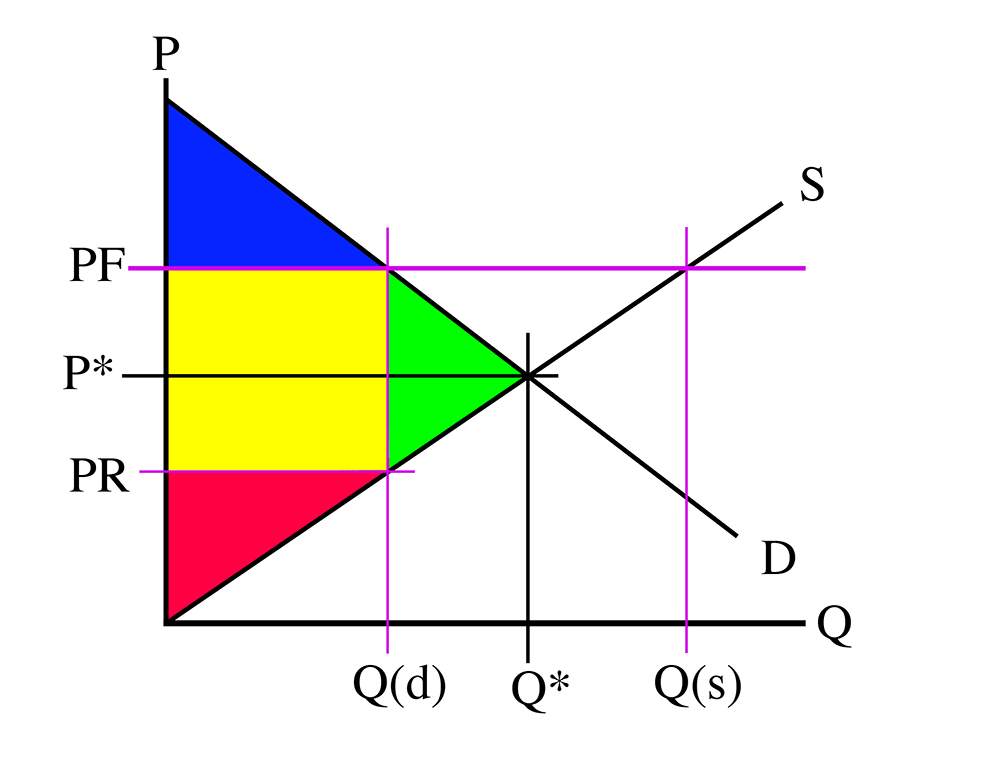

Let’s look at a supply/demand diagram with a price cap.

In this diagram, we have a price cap, PC, which is a horizontal line below the equilibrium price, P*. The quantity demanded, Q(d), is the amount at which the price cap and the demand curve intersect. The quantity supplied, Q(s), is where the price cap and the supply curve intersect. From the diagram, you can see that Q(d) is greater than Q(s). That is, we have more people who want to buy than we have people who are willing to sell. This should be obvious – if the price is lowered, more people will want to buy.

So, in this market, the supply is unable to meet the demand. So there is a “Shortage” of the good in question. Only some of the demanders get to buy, but they do get to pay a lower price. We have a new equilibrium, which is defined by (PC, Q(s)), which is at a lower price and quantity than the free-market equilibrium, (P*, Q*)

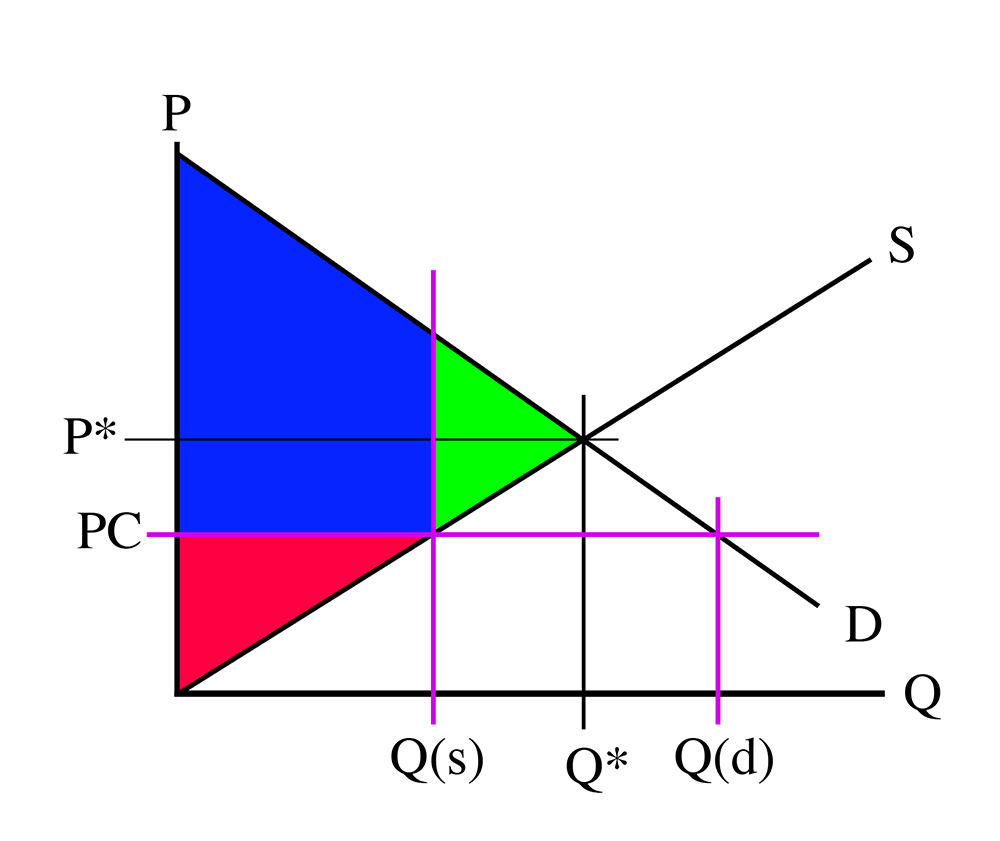

What about the consumer and producer surpluses?

We know that the producer surplus is the area between the equilibrium price and the supply curve. In the above diagram, this is the red area. Obviously, this will be smaller than in the free market. The consumer surplus is the area between the demand curve and the equilibrium price, which is the blue area in the above diagram. We do not know, without numbers, if this is larger than the free-market consumer surplus. But we do see that some wealth has been transferred from the producers to the consumers (or so it seems – more on this later.)

The green area represents the buyers and sellers who would be able to trade in a free market but are unable to in the controlled market. Because they cannot trade, they gain zero wealth from this market instead of some wealth. So, the green area is wealth from trade that is lost to society. This area is called the Deadweight Loss. It is a loss in wealth caused by a price control.

Now, think about the “shortage”. We have more buyers than sellers. Usually, the buyers will compete with each other by offering more money. But they are not allowed to do that here. But they will compete in other ways. They will wait in line longer. They will get out of bed earlier and show up at the shop earlier. They will buy from people on the black market. The people who want the goods the most will compete until they have the goods.

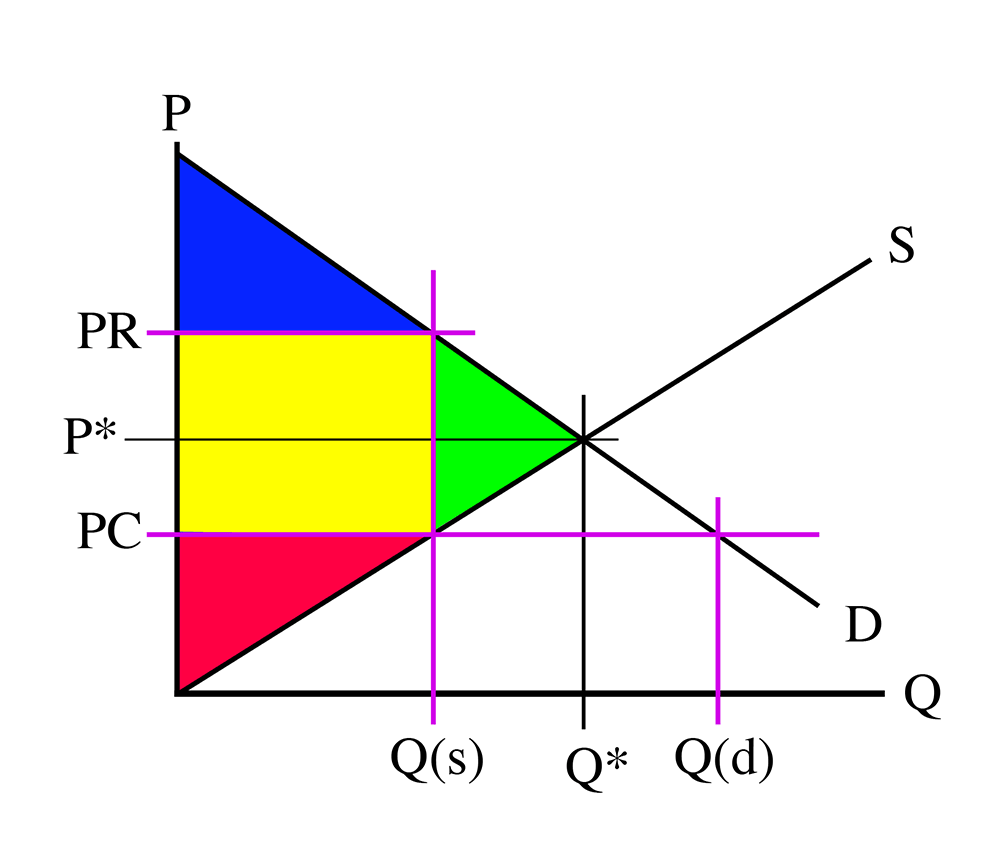

They will use up resources (time, energy, money) in this competition, but those resources will not go to the seller. Instead, they are lost to society. If we look at the following diagram, we will see that the buyers will compete until the price has been driven up to the level called “PR”, the “Real Price.” Only people willing to pay more than PC will end up with the goods. The most they are allowed to pay in cash is PC, but they spend PR. The area between PC and PR is called the “hidden costs” – hidden because they are not observed in the official transaction. They are the costs of competing for the goods and are lost to society.

So the “hidden cost” is the yellow part of this diagram. The green is the deadweight loss, and the consumer and producer surpluses are shown in blue and red. As we can see, the “real” wealth, the producer and consumer surpluses, are much smaller than they would be in a free market.

You will also notice that the “Real Price,” PR, is higher than the equilibrium price, P*. The original goal was to lower the price, but we have ended up raising the price. Trying to help consumers by lowering the price has actually raised the price.

Example

Suppose supply and demand functions in a market are given as:

Find the completive market equilibrium price, quantity, consumer surplus, producer surplus, and total wealth.

Determine the impact of the price ceiling

is extracted from supply function by setting the price as :

And can be found from demand function by setting the price as :

As we can see supply quantity, , is less than the competitive market equilibrium, while the demand quantity, is higher.

And Real Price, PR, can be found by plugging the into the demand function:

In order to find the consumer surplus, we need to calculate the area of the blue trapezoid. Please note that is the top right corner of the trapezoid.

Producer surplus will be:

And finally, Deadweight Loss can be found in two ways:

Calculating the area of the green triangle:

Or deducting the TW with price ceiling from the completive market TW:

Hidden costs can also be calculated as:

Price Floors

Sometimes, a government wants to help producers by setting a minimum price below which people are not allowed to buy or sell. This is like the price cap in reverse. For example, in Pennsylvania, there are minimum prices on milk, which is designed to help milk producers get a "fair" price for their product. In Maryland, there are minimum prices on gasoline, which are designed to stop "big" sellers from dropping a price so low that competitors would be driven out of the market leaving a monopoly (as you will remember, this is called predatory pricing, and most economists believe that it is basically impossible to make work successfully). In the 1970s and earlier, airlines had minimum price controls, as did brokerages for buying and selling stocks.

Much like price caps, this form of price control often serves to hurt the people it is seeking to help.

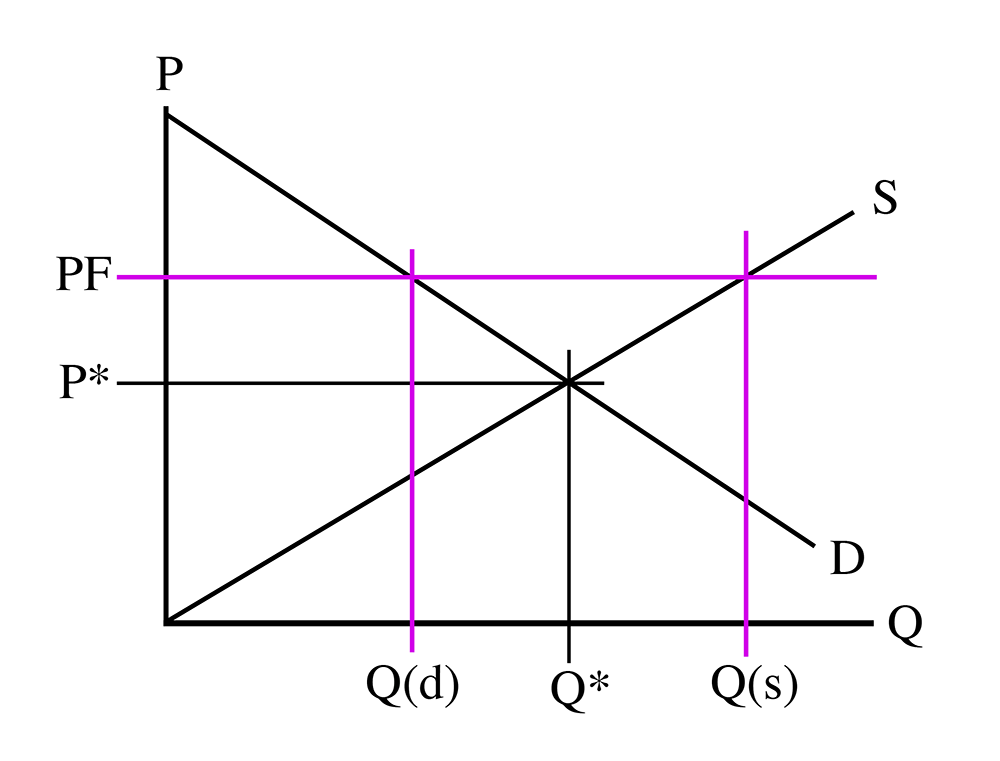

Let's look at a supply-demand diagram. In this case, the government sets a minimum price that is ABOVE the free-market equilibrium price.

Note: if the price floor is below P*, it will not make any difference to the market. It will be “non-binding.” A price floor must be higher than P* in order for it to have any effect.

Now, in this case, the quantity demanded, Q(d), is lower than the quantity supplied, Q(s). We have more people who want to sell than we do people who want to buy. The new equilibrium is given by (PF, Q(d)). This is the opposite of the price cap: that gave us unsatisfied demand, which we called a shortage. In this case, we have an unsold supply, which is called a "glut."

In this case, instead of consumers competing to buy, the producers will compete to sell. In a competitive market, producers compete with each other for customers by lowering their price. But, in this case, they are forbidden from lowering their cash price below the official floor price. So, instead, they have to find other ways to compete with each other. The most common method is to compete on service. I mentioned the case of airlines being regulated up until the end of the 1970s. After President Carter deregulated the airlines, they were free to compete on price, meaning that they no longer had to try to offer better service than each other. So now we have the common complaint that flying is "no fun" anymore - planes are crowded, seats are crammed together, you get charged extra to check bags, there are no more meals on flights, no more free drinks, no more pillows, and blankets. However, the prices are certainly very much lower. I can fly from New York to Los Angeles for about $300, which is less in nominal dollars than I would have paid in 1978, when a similar flight was about $550. And that was in 1978 dollars, which would probably be worth about $1500 today - and fuel and labor costs were a lot lower in 1978 than they are today. The reason for this dramatic price drop? Competition following deregulation (removal of the price floor).

There are many tactics for competing in non-price ways. This might mean giving better service, as illustrated above; offering free delivery; giving away stuff for free; or selling “under the table” at prices below the “official” price, that is, entering a "black market" situation. Sellers will compete using these non-price tactics until only those sellers to the left of Q(d) will sell. If we fill in the areas on this diagram, it looks a lot like the one for the price cap:

Once again, the yellow area is the “hidden” costs, the difference between the amount of cash the sellers receive, and the wealth they gain after competing. Once again, the real price is actually below the free-market price that the government thought was too low.

Price controls are usually used because of good intentions on the part of the government, but it is clear that they usually end up hurting the people they are designed to help.

Example

Following the previous example, determine the impact of the price floor

We learned that the completive market equilibrium:

If price floor of imposed to the market, then:

can be found by plugging the price floor into the demand curve:

And can be found from supply function by setting the price as :

Price floor causes supply quantity, , to be higher and demand quantity, , to be lower than the competitive market equilibrium. In this case we will have excess supply to the market

In case of price floor policy, Real Price is determined by the supply function and can be found by plugging the into the supply function:

Consumer surplus is the area of the blue triangle:

Producer surplus is the area of trapezoid (red triangle + yellow rectangle):

Deadweight Loss can be found in two ways:

Calculating the area of the green triangle:

Or deducting the TW with price ceiling from the completive market TW:

In case of price floor, consumer surplus decreases and producer surplus increase. But, TW is decreased. Note that we have excess supply in the market. However, price is so high that some consumers can’t buy the product and it creates the Deadweight Loss.

Hidden costs can also be calculated as:

Summary and Final Tasks

In this lesson, we studied the behavior of firms with respect to obtaining favors from government agencies. Such favors can be in the form of contracts, regulations, price controls and import restrictions. The act of competing with other firms for these favors is called rent-seeking, as it is an attempt to obtain "unearned" economic profits. This behavior persists because of the idea of concentrated benefits and distributed costs - such behaviors can reap huge profits for the firms that are successful, and the costs are spread out over large swaths of the public who do not often have a rational basis for combating them because the cost of fighting is greater than the benefits obtained by an individual.

We then examined two types of government intervention: the setting of price floors and price ceilings. We showed that these attempts to modify the price that would be observed in a competitive market actually end up hurting the people they are intended to help: price caps cause shortages, and to obtain the goods in question, consumers have to compete with each other in non-price ways, such that the "real" cost ends up being higher than it would be in an uncontrolled market. The same is true of price floors, which lead to gluts, and force suppliers to compete with each other in non-price ways, often costing them more than the extra cash they are earning.

In the next lesson, we will start looking at some topical issues in energy and mineral economics, such as resource scarcity, climate change and energy security.

If you login to Canvas, you will find the task to be completed for this lesson: an online multiple choice quiz.

Have you completed everything?

You have reached the end of Lesson 9! Double check the list of requirements on the first page of this lesson to make sure you have completed all of the activities listed there.

Tell us about it!

If you have anything you'd like to comment on or add to the lesson materials, feel free to post your thoughts in the discussion forum in Canvas. For example, if there was a point that you had trouble understanding, ask about it.