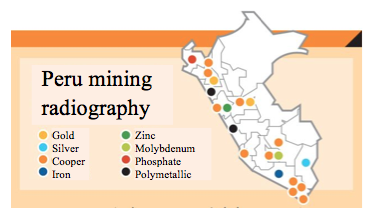

Peru has been blessed with natural resources, such as gold, silver, and copper, as the map below indicates.

For centuries, the export of minerals has brought more foreign exchange to the country; however, these have also been a source of social conflict in places where the ore is extracted.

Peru - an Example of Resource Curse and its Evolution

Many pre-Columbian gold artifacts have been found in Peru, such as Tumi, a ceremonial knife, and textiles whose tissues are threads of gold. The story goes that the Spanish conquest of Peru in the sixteenth century began when a group of soldiers took the decision to go to South America to become rich, because the rumors spoke of “El Dorado,” a region where everything was made of gold.

Today, the gold, silver, copper, iron and other minerals, as well as oil and gas, represent the abundance of natural resources for Peru. Exports of these natural resources are the main source of foreign exchange for the country.

Extractive activities are performed by state enterprises and private companies. These companies pay large amounts of taxes. These taxes become the source of resources that are distributed between the national and local governments.

Peruvian history shows that the country has been inflicted with the resource curse for decades, and this condition has delayed Peruvian economic and political development. Peru, as with other many Latin-American countries, has suffered from a lack of political institutions and military governments that try to use the resource abundance as a short-run solution to economic challenges. After many years and a large political crisis caused by the Shining Path terrorism movement in the 1980s and 1990s, a new economic and political order was established that has been the base of current economic development.

Peru Looking for a Different Path: Managing the Resource Curse

Beginning in the mid-1990s, the Peruvian government employed a set of measures that caused a structural reform of the country. In the economic sphere, the aim was to make Peru more open to trade and investment and to have stronger institutions in the field of economic management. Such institutions include the Superintendency of Banking and Insurance, Tax Authority, Superintendence of Customs Administration, The Central Bank, The Ministry of Economy and Finance, as the more representative institutions among others.

The economic discipline that has followed this change in policy has allowed the Peruvian economy to grow. In these years Peru has been able to develop productive capacities and services in areas other than those of the extraction of natural resources. This has meant that today while mineral exports represent an important source of foreign exchange, these are not as in yesteryear, the largest single source. There is now a local productive chain capable of exporting products such as textiles, food, financial services, and gastronomic services among others. (To enjoy the benefits of this new policy, we suggest you check out your local Peruvian restaurant.) All these changes have reduced the extreme dependence of Peru on natural resources.

While there has remarkable economic progress in Peru, its political institutions have not advanced as far as one might wish. For example, it appears that much of the spending of local governments benefits the elite few and not the wider population. Studies show that, in 2013, 90% of local authorities have been the subject complaints of corruption and misuse of funds.

The Stress of the Resource Curse

Mining has brought some conflict to the village where the ore is extracted. A good summary is contained in the video below (7:25).

PRESENTER: Mining is Peru's engine of industry, and it's enabled the country to make huge economic strides in the past decade. It has experienced a growth average of more than 6% a year since 2002, but it has also sparked controversy. There are growing concerns that its mining practices cause contamination and don't generate sustainable development for those who live around it. Correspondent, Dan Collins, takes a hard look at the industry to show us how this rich, natural resource is also the subject of deep debate.

DAN COLLYNS: Demonstrators in Lima calling for a new president-- the effect of a weakened world economy on Peru's mineral exports or a whole range of demands and complaints. There were just a few miners at this march in the Peruvian capital, but many argue that mining is at the heart of rising public discontent.

The job with the international commodity prices has a direct effect on the mining royalties received by millions of Peruvians across the country. If the boom in Peru is coming to an end, they're going to be seeing a lot more riot police on the streets of Lima. Every day, tens of thousands of tons of copper ore, zinc, lead, gold, and silver leave the capital's Callao port-- raw materials that fueled the Peruvian boom for more than a decade.

But in the first six months of this year, mineral shipments were down by 12%. Industry insiders say some $22 billion of mining projects aren't getting launched fast enough to keep Peru's economy ticking along at its usual velocity-- something President Ollanta Humala didn't plan for.

MIGUEL SANTILLANA: He thought that postponing decisions, postponing the beginning of projects was OK, and nothing was going to happen. Well, two years down the road, he understands that he needs the investment, because the Peruvian economy has been freezing down since March of this year. And if we grow at 4.8 by the end of this year, it will be very good.

DAN COLLYNS: It's a more than respectable growth rate. But Peru's got used to growing at an average of 6.4% during the past decade. While some say the bust is just around the corner, others say the boom is good for a few miles yet.

CYNTHIA SANBORN: We're still in a cycle of relatively good prices. This drop is temporary and brief. We still have a window of opportunity which not only are prices going to remain healthy, but also production is coming online.

It's not just an issue of prices. It's also an issue of new production. So we say there's another 10 to 15 years of healthy growth of the mining sector. And therefore, public revenue is generated by such.

[CONVERSING IN SPANISH]

DAN COLLYNS: But many in Peru question whether mining, for all the big capital it attracts, benefits the communities around it. Pollution and competition for water have generated hundreds of conflicts and derailed dozens of mining projects. Even the biggest potential investment in the country's history, the $2.2 billion Congo gold mine, couldn't get off the ground due to local opposition.

But some mining executives are taking the unpopular path of shaking up the status quo. Diego Benavidez, president of Minera IRL, is the first to make the community around a mining concession shareholders in its profits.

DIEGO BENAVIDEZ: What I earned was a lot of enemies. It was not easy to impose a formula like this where at you have a lot of private mining going in Peru. But we had very clear that if you want to develop mining in Peru, you have to have a partnership. In this case, this 5% is a 5% shareholding. And they have the same rights as any shareholder in the goods and in the bad moments.

DAN COLLYNS: Minera IRL's existing Corihuarmi mine also leads the pack in good community relations as evidenced by local resident, Melesio Quispe.

MELESIO QUISPE: The company is helping by training the women to improve their textiles. It's planting trees and plants. And the latest help they've given us is to build a hotel in our village. We, the men, take it in turns to work here at the mine.

DAN COLLYNS: Quispe earns more than $400 a month to turn this mining tailing back into pasture. It's a small fortune in his village. Meanwhile, some 5 kilometers above sea level, miners use nonpolluting technology to get gold out of the ground.

It's not Peru's biggest, nor its most profitable mine. But it runs 24/7, showing that there's a cost benefit to keeping the locals on-site. The business of getting minerals out of the ground runs as deep in Peru's history as the seams of metal in its mountains.

But Peru's relationship with mining is full of paradoxes. The industry, which provides 60% of Peru's exports, provides employment for just 1% of its workforce. It's a subject of much debate.

VERONIKA MENDOZA: An excessive dependence on mining is not healthy for our economy, when the state should be worrying about diversifying the economy, and thus, avoiding all the anxiety caused by the recent drop in commodity prices which caused a big commotion here, a cut in mining royalties and social programs.

DAN COLLYNS: Peru's history is full of booms and busts. Providing the raw materials that the world needs right now is never going to provide long term stability.

For projects which are under development with approved budgets, like Toromocho, like Las Bambas, and Cerro Verde, there's no reason why there should be any delay. We are predicting that we will more than double our copper output from 1.8 million tons to 2.8 million tons.

DAN COLLYNS: How that revenue is invested-- building infrastructure, tackling poverty, improving education-- will be key.

CYNTHIA SANBORN: Peru has one of the worst public education systems in all of Latin America. We know what needs to be done. There's a significant amount of investment and political will that has to go into improving education.

And if that isn't done now, thinking about the long term, the labor force and the alternative economic activities that we would like to see are not going to take place. We're going have a population that's not capable of different kinds of entrepreneurial activity.

DAN COLLYNS: For now, no other sector is as productive or can generate as much income as mining. Used the right way, the industry could provide Peru with a panacea for its ills and serve as its salvation for the future.

From 2004 to 2014, the Peruvian economy grew at a very strong rate of six percent per year. Much of this growth, however, was driven by unusually high resource prices. As the video linked discusses, commentators in Peru became concerned as resource price soften in 2014. Their concern was that the society had become accustomed to economic growth. If the price of resources fell, economic growth would be reduced or eliminated, leading to social unrest.

There are other sources of social unrest. The people who live near mining projects are often concerned about the environmental effects of such projects. There are often political demonstrations opposing mining projects. This has led to a delay or sometimes a denial of permission to being mining from the government.

The source of opposition to mining projects appears to come from several sources. First, local residents often do not benefit greatly from mining projects. This may occur because they are poor negotiators, or because their local leaders do not always have their interests at heart. In addition, local residents often have limited access to judicial systems. Thus, if a mining company violates a regulation or an agreement it has with a community, the local people may have difficulty forcing the mining company to comply with regulations or live up to its promises. Another way of looking at this is that mining companies who do desire to support their local communities may have a difficult time showing that they are committed to such a policy. They, therefore, may have trouble gaining the support of nearby residents, even when the mining company will act to improve the quality of life in the region.