Lesson 3 - Basic Accounting and Corporate Finance

The links below provide an outline of the material for this lesson. Be sure to carefully read through the entire lesson before returning to Canvas to submit your assignments.

Lesson 3 Overview

Lesson 3 Overview

Overview

Steve Jobs and Bill Gates started their respective companies (Apple and Microsoft) in their garages. That makes for a nice story, but how exactly did these companies go from garage-band material to global behemoths? They had to raise money or "capital" somehow - there was only so far that Steve Jobs' own bank account (or his parents' bank account) was going to take him. Eventually, both Jobs and Gates needed to seek additional capital from various sorts of investors to help their companies grow - there is, after all, an old saying that it "takes money to make money." True enough; in this lesson, we will take a bit of a closer look at the process of raising capital, from venture capital to stocks to bonds. The world of corporate finance can get very murky very fast; and, in some ways, it's more of a legal practice than a business practice. Our focus is going to be on understanding the various mechanisms that are used to finance energy projects and the implications of those funding mechanisms on overall project costs.

Where we will ultimately wind up is at this mysterious quantity called the "discount rate." Where does that come from? When we are looking at social decisions that involve common costs and benefits, the discount rate is usually more of a matter of debate than anything else. But when a business decision is involved (and that business is a for-profit entity), then there is a rhyme and reason behind the determination of the discount rate as the "opportunity cost" of its investors. There are many different types of investors in a typical firm or project, all of whom face different opportunity costs, so we will encapsulate these in a single number called the "weighted average cost of capital" (WACC). The WACC turns out to be the correct discount rate for a company or a project.

Finally, most of the material that we will develop in this lesson is targeted toward for-profit companies making investments that are expected to earn some sort of positive return over a relevant time horizon. We won't talk much about the non-profit sector except at the very end, when we discuss how the deregulation of commodity markets has changed the investment game for many for-profit firms, but not necessarily for publicly-owned or cooperative firms. If you are interested specifically in project finance concepts for non-profit firms, the Non-profit Finance Fund [1] has some good resources available.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Discuss topics related to Basic Accounting and Corporate Finance

- Explain the fundamental difference between debt and equity financing

- Identify different types of equity investors

- Calculate the cost of debt and equity financing for a single company or project

- Using the cost of debt and equity financing, calculate the weighted average cost of capital

- Determine the client, locale, and major stakeholders for your project

- Develop a preliminary Project Charter and Stakeholder Register for your project

Reading Materials

We will draw on sections from several readings. In particular, there are a number of good online tutorials on the weighted average cost of capital. If you want to get deeper into this subject, there is no substitute for a good textbook on corporate finance. The all-time classic is Principles of Corporate Finance by Brealy, Myers, and Allen (672 pp., McGraw Hill). This book has gone through a number of editions, so earlier editions are probably available online for relatively little cost.

Please watch the following video interview with Elise Zoli (43:45). If this video is slow to load here on this page, you can always access it and all course videos in the Media Gallery in Canvas.

ELISE: Sure. But first, I'm going to start by saying it's an honor and pleasure to be here. And there's no one that I'd rather talk about this stuff with than you. Thank you. My background is I'm a lawyer, I am middle aged, have worked in law exclusively in the sustainability space for more than two decades. I went back to school, that's a family thing, and I also have my MBA.

MARK: Great, actually, so, how did you end up choosing the law as a profession?

ELISE: For me, when I started practicing law, there were a number of new laws that were transformational about how we approach our economy and our collective prosperity. And I thought that these new laws were going to alter the way that we decide to move money in the world. And I really believed that if we were going to design a better economic structure worldwide, that we all had to participate and show up and figure out how to do that right... Right. So I was a big fan of these new ways of thinking of integrating sustainability, of integrating carbon and new currencies and integrating diversity and equity. And I'm a small woman, middle aged, Italian. I could see that if we were going to have a more prosperous, more fair economy, that we had to do things differently. And I was excited to be part of the team thinking about that. Right. Great. You're at Wilson Sonsini now, what are your current duties there? Yeah. Wilson Sonsini is somewhat of a unique law firm. It was created for the new economy. We help entrepreneurs, founders and innovators make the great leap forward. And it was a natural place for me to be... because we work shoulder to shoulder with people who are thinking about how to design the new world. And that's the form of service and support I like to provide.

MARK: Tell us about some of the kinds of projects you work on for WS.

ELISE: Yeah, I'm a little bit of a different critter. Like I said, I'm granola, crunchy. I've only worked in the sustainability space, but I have worked in forms of clean energy that maybe are broader than many people think of them. I've worked in Fission. I've worked in Fusion. I've worked in regenerative farming. I've worked in advanced forms of fuels. Okay. Particularly hydrogen. And I've worked in ways of thinking about how we structure waste and water more than the average bear. And so I think I view energy in the real physics sense of the term, right? Any caloric flux is really important to me. And I'm going to encourage you and your students in this conversation to think broadly about what we mean by energy. Right. And I think that's what's good for their careers.

MARK: Right. Well, it's interesting because one of the things that we show at the very beginning of, of the course is a, a graph that shows 67% of the energy being rejected. And that's something that's near and dear to both of us, really appreciate you bringing that up and how the caloric flux, that's a great way to talk about it.

ELISE: Exactly Right. And I think that I'm going to talk about, in very particular terms, what I do, which is principally to move money. But I think it's really important that we start to get people to think differently about energy and how it's used. And my daughter is 12, my son is 19, and one of the things you can see in their eyes and the way they behave and the way they think about the world is that my daughter grew up with plug-ins, hybrid vehicles and electric vehicles as the norm. And my son grew up with internal combustion engines. For my daughter, she really doesn't understand why people would want to leave their house to fuel their cars. She doesn't understand why public infrastructure is necessary. That all seems illogical to her, right, because she's used to this intrinsic convenience of why would you leave your home to go fuel your vehicle to come back home. That way of thinking she doesn't understand. And one of the things that I really encourage people to do is as they're thinking about the future, try not to see it so much with the constraints we currently have, but really see it in the way that you can help be part of that innovation team that's designing for something different. Right. That means, I think necessarily seeing the things that Bill Gates and Stephen Jobs and all of these extraordinary people who looked at the way that we shared information and said oh, we can do this better and faster. Right. We have to do that with energy. If we do that with energy, I think we're all going to be exactly where we want to be.

MARK: All right. That's great stuff. Tell us a little bit about the work you do for the Stimpson Center.

ELISE: At the Stimson Center, I'm on the board of directors. I'm always going to encourage people to think about participating in the not for profit side of the world, as well as the for profit as we build this new economy. You're going to see there's a blending of those. Heat is a perfect example, Right. Under the new EPA program to allocate $27,000,000,000 to national not for profits to be able to drive the finance of the new economy, right? There's this belief structure that not for profits should be the recipient of these funds. That's not the way we thought about things a decade ago. Right. No one stood up and said, yeah, let's give our money to not for profits or NGOs or to states. But what we've learned based on great data is that allocation of federal and state capital makes a huge difference. So getting a DOE grant makes a huge difference to your future. And that non dilutive capital, that capital that doesn't have to be repaid in the same way as a traditional loan or traditional equity investment would have to be paid, is transformational of how companies and how entrepreneurs advance and succeed. The Stimson Center is a not for profit, nonpartisan think tank that focuses on advancing a safer, more peaceful, more prosperous future. I'm part of the Stimson Center and a co founder of the Alliance for a Climate Resilient Earth. Which is designed to allow some of the leading institutions on earth, the national labs, universities, and corporations, to come together and talk about strategies for advancing a sustainable supply chain, better technology and ESG thinking into their systems and structures. We do that because we believe that convening makes a difference. We believe that if you don't give people a place to talk about how they're working together, you don't spread the ideas as fast as you otherwise could. That's my reason for being at the Stimson Center. The underpinnings of that and my decision to participate at the Stimson Center came from work that's being done at Brookings. I'm going to encourage everyone if they haven't, some of my favorite science out there, If you haven't looked at the geography of prosperity, the Hamilton project at Brookings, I'm going to encourage you to go there and take a look at what, and how we build prosperous communities. That places that you'd want to live and that your students want to live and raise their children, rear their children. And I think it's really important to see what the fundamental underpinnings of prosperity are. And they're education, innovation, diversity. That's an oversimplification, but only slightly, and that's where we need to get to.

MARK: Right. Great, thank you. So take it down a little bit to the blood and guts of this. Can you give students a glimpse into how a simple structured finance transaction might work?

ELISE: Yeah, so let's talk about capital stacks, right? And just money, how does money help you advance? Ten years ago and 20 years ago, if you were a new company, you went out and got equity. And you built your first things and then you built your second things and your third things. And hopefully they worked and then maybe you went to a different bank and you got some working capital or line of credit to fund your business. And then you went out to a third bank to get project finance. And that was mostly blended equity and debt, but much larger than what you started with with your venture capital. Today, many of those lines are blurred. They just are, and particularly for clean energy, climate solutions, climate tech, and clean tech companies. It's very rare that they're building a company and then going out and having a project. Usually, the company's success depends on their having a project that works, right? And that's particularly true for fusion and fission, right? If you don't have a reactor, if you don't have a Tokamak, you don't exist. Right now what we've started to do, and some of this is as recent as a year ago, some of it's as recent as seven years ago, is we've started to redesign the capital allocation to better suit the companies, as opposed to forcing the companies to go out and do different things. Right. And now, there are absolutely great groups of investors out there. I'm going to give some examples. They are not meant to be talismenic, they're not meant to say you must look to these entities, But they are examples of enterprises that are investors that are providing the full capital stack in a different way. So today we would tend to have blended finance, where you go out and you get from the same investor some equity for your corporation and then some finance for your first project all at once. Okay. And in Boston, you know, that looks like Creo Syndicate or Spring Lane Capitol. Any number of great investors out there that are really focused on climate solutions and understand you've got to provide both. It often looks like great family offices who are really focused on both allocating the capital but also making sure that the sustainability metrics, the carbon reductions, the emissions reductions, the waste reductions, all of those alternative currencies are all being met as well, Right? Right. So today I think that the thing that if I were an entrepreneur I'd want to know most and best is that you get to design your own capital stack and you're going to fall within the traditional norms of the last 25, 50 years, but you also can cross those norms as an early stage company. Then I'm going to suggest as well that every single early stage company in our space is looking at the capital that's afforded by the federal government. In the United States, under the IRA and BIL, state governments like California, New York, and Illinois. The green banks that are out there. There are 21 green banks in 16 states and NDC. And trying to think about new forms of relationships to be able to move their company forward with aligned capital. Does that help?

MARK: Immensely. That's just great stuff for the students. When Elise says capital stack, we're talking about capital structure for your project. That's important and to the extent that you're doing your project and students are... they do a project, that's the whole course, that this is a very important piece of how it all fits together and what that capital structure looks like. So feel free to not necessarily stay in that debt / equity realm, but you can fuse them as Elise is saying and if you want to, you can even say that the ... the investment tax credit, is a form of capital, If you're so inclined to look at it that way.

ELISE: I absolutely agree with you. I think that LC, the California Systems for Supporting Innovative technologies and projects, the federal systems are critically important and they are forms of capital. And let's just call capital what it is. We're just talking about money here, right? And what we're really talking about is when you build your first project, who is willing to come in and give you money to be able to do it? Right. And if you think about the different spaces, in the nuclear space, that almost can't be done without the Department of Energy. Right. In the solar space, that really shouldn't be done, without, if you're doing it on farms, the USDA. If you're doing it in a traditional industrial context, Department of Energy, or the tax incentive systems. If you're doing it in California without the LCFS system, right? If you start to think about those forms of capital, of money and/ or incentives which are surrogates for capital, then all of a sudden you can start to get to a capital stack, or a money stack that is more than 50 to 70% of what you need to be able to do your first project. If you can do that with government money, which is customarily given to you without an expectation of a return on that investment, then that allows you to build a project with a lower risk of failure, a higher return to your investors seeking returns on investment. And object to, so it should go more easily, better and faster. And in fact my experiences, they do. Right, right. It's, the term we use is leverage, straight, straight, straight, straight, straight and simple. Right? And that's, that allows us to lever things up and get the returns on the equity higher. But I also would say that in this world, it is now reasonable to expect that the private capital is more reasonable in their expectations about a return on investment. So the wealth transfer from the federal government should be in part to the company and in part to their investors. I would not ordinarily want to see 100% of the non dilutive capital that the US government or states are providing, going 100% to investors, right? Because that's too much, right? Right. Agreed. Part of the reason we have project finance is because it should be a lower IRR, right? A lower return on investment, right, than for traditional equity at the venture high risk stage, right? Does that make sense? Or is that too much a level of detail? No, no, that's perfect. This is all great stuff. You mentioned project finance. Why is project finance such an important concept when it comes to funding energy projects? Yeah. Essentially it's the whole ball of wax, right? It is the center of energy projects. And it's because in order to be able to finance projects, we have to come up with both a structure, committed line of capital and a repayment system that allow people to believe that they will, that their money is not being thrown away. It's that simple. And project finance does that by providing a security or a right, a legal right with respect to some of the equipment. Right. That's being constructed. And if you think about solar, for instance, 70% of the typical cost of a solar installation is an equipment that can be repurposed. Right? Right. And so there's downside projection for the investors. Right? And that's why much of the solar agreements that you'll see talk about rights in case the project does not go forward. Right, right. And part of the complexity of project finance and part of the fun of it from our perspective. Is that a lot of what you think about is how you get the electrons out. Get the electrons paid for at the right price. And then how that allows you to return value to your investors, right, while reducing risk. That's the whole ball of wax, right? And when for all of your students that are going to structure these transactions, if you can reduce them to their most simplistic formula, then it becomes much easier to design them to get people aligned and stop. A little bit of the complexity that I think sometimes turns these agreements into something less efficient than they could be.

MARK: Right, right. Exactly. So really appreciate that. Very enlightening I think, so. Do you think there are any policy levers you'd like to see pulled to move along the transition in your mind either at the state level or federal level?

ELISE: You know. So I don't litigate very often, but I have litigated including in the United States Supreme Court in favor of a new economy, and carbon. Accurate calculation of adverse impacts is the way I'd really say it and a way of reducing impacts. Because if innovation means anything, it means doing more with less, right? Right. Not doing less with more. We have hit our ecological limits and less with more is no longer an option, right? And so the question is, how do we have a consensus discussion about what doing more with less looks like? And I'm open to many and different ways of doing that, but while we have the dollar in the United States as our fundamental currency, it seems to me that we should put a price on impacts. Right? Right. So I like all forms of carbon tax. I think they work fairly reasonably. There is something called an internal carbon price and most large corporations actually already do this internally, right? And so there are surrogates that are in place because we don't have, you know, a national mandatory carbon markets, a carbon tax, or another system for assessing, valuing projects, particularly clean energy projects that outperform their peers by having lower impacts. As a consideration. So, from my perspective, I would set up three forms of values. The first, I would have a capacity factor, installed capacity value nationwide. Are you there? Are you reliable? Can you provide power when needed? And I would put a price on that. Secondarily, I would put a price on the reduced impacts associated with your project. Third, while no one talks about this, and it's probably slightly out there, I would put a security framework around the energy resource and what it's providing, so that, to the extent that, it's likely to experience much lower supply chain disruption. To the extent that it can work, um, outside, and readily integrate its electrons within the grid, or sell its fuels into an existing system for transporting fuels. I would put a high premium on that because I think we as a globe, have begun to experience significant disruptions, both extreme weather and now, pandemics and also armed conflicts that we didn't expect. Right. And I think we have to prepare better for all of those. And that means that we have to start thinking in terms of security.

MARK: Yes. And I mean, resiliency of the supply chain is, obviously, I think that's what you're getting at there.

ELISE: Resiliency of the supply chains, ability to be deployed in isolation. Distributed power has an enormously high value, right? Redundancy, which we don't value at all, to me has an enormously high value, and so I think that what Europe has learned. And thankfully with a very warm winter, is that you can't have overdependence on a single source of fuel.

MARK: Very true.

ELISE: Or a single force of electricity. And I think it's time that we got our hands around that. In a more mathematical, I'm a mathematical being, we've got to get our hands around that in a more mathematical way.

MARK: Right. Right, exactly. To talk a little bit about that, maybe even take that conversation a step further, what about the notion of economic justice? Just transition for labor and capital and that kind of thing. I mean, do you think there's maybe maybe a place for a price tag on that as well? I'm just bringing that into the conversation because you got me thinking about that.

ELISE: I'm a huge believer in equity and of valuing equity. Some years ago, my team and I worked on and designed the first human health metric, to my knowledge, that valued clean energy production by showing the avoided morbidity, mortality, lost work days, healthcare costs associated with some forms of electricity. The idea was that if we're going to have a functional, prosperous, integrated society, you can't have disproportionate burden of certain forms of disease. And I think that increasingly that discussion is being rephrased. It's better, as equity. Right? Right. So I absolutely believe that a society that is healthier, on balance, will achieve more, right? For my, MBA, I did a significant amount of work looking at the effects of war on multigenerational effects of conflict. And in particular looked at epigenetics, which is where even though you and I fought in war wars, but our children did not, but nonetheless experience increased rates of depression and related conditions because of the effects that you and I experienced in battle. And if you start to think about epigenetic effects and you start to calculate, and this is a very early field, I don't want to suggest otherwise, and the science may prove out differently. But right now, what we believe is that conflict has a long tail. And what we mean by that is that living under extreme circumstances is... affects not only the generation that experiences it, but follow on generations, right? In material ways. So I believe we have to think about diversity as equity and inclusion, as building a better society. One that is able to participate in a meritocracy. And if you adversely affect some parts of the population disproportionately and significantly, then that has a serious cost directly, but also in a multi-generational way. Right? So I believe that it should affect whether we wage war. I feel like that should affect whether we have disproportionate negative impacts on certain portions of our population, and I believe we should do everything we can to remedy that.

MARK: Excellent, appreciate that. Are there any other markets or conditions that are affecting project finance in a manner that we might not have anticipated three to five years ago? Inflation.

ELISE: Absolutely. Absolutely. I'm going to say some of this is actually closer to home. I think that the shift to electric vehicles is having a significant multiplier effect. Not only on the way we drive and how we perceive that experience, but also how electrified our homes are, where we allocate electrons and what the future looks like. And I think that we, as a group, and I include myself in this, did not fully appreciate how quickly we would accelerate vehicle electrification for light vehicles. I think we have not fully appreciated how quickly we're going to need hydrogen for long haul trucking and heavy vehicles. And transformational... what a transformation that's going to be on the way we fuel things and how we produce fuel. Right? So if you're using electrolyzers that's not 3 mi below the ore surface, right? Right. All of a sudden now you're going to start to see fuel production around you. That's going to be a very different structure.

MARK: Right. Right.

ELISE: Then lastly, I think that we haven't begun to think hard about food production and in particular, you know, carbon capture utilization and sequestration. I think we're in what people refer to as hype cycle one, but version 1.0 you have many CCUS, that's the acronym, technologies, right? And I think that they are going to be extraordinary. Nothing short of extraordinary in the near term, in terms of how we manage for climate, for carbon and emissions, other air emissions. So it would not surprise me if three years from now we find that our ability to produce cementitious materials from CO2 two has transformed the way we think of cement production, right? And therefore, what we think about CO2. And I would not be surprised to find that we go from thinking of CO2 as a waste to be avoided or sequestered to a feedstock to be repurposed and used efficiently. That's what I'm hopeful for, right?

ELISE: Right. So what are the biggest challenges facing your business in today's energy markets?

MARK: I think, you know, we're gladiators. Mark, you know this better than anybody else, right? The difficulties of being in a new space, an emerging space is that often you have to explain yourself, you have to educate, you have to surmount the both lack of awareness, lack of understanding and fear people have about new things. And always remind myself that there must have been a moment, I know there was a moment, right, where the CEO and the Board of Smith Corona, the leading typewriter manufacturer of the '70s, were in a room, and a consultant accountant and a law firm and the boards on the CFO all got in the room and someone said, there are these two little companies. Should we buy Apple? One's called Apple or some fruit. One is called...does the stuff that's used to make apple thing work, and it's called Microsoft, and should we buy them? And the price on those guys was what? Maybe 5 million, ten million dollars, right? And the board of Smith Corona, which had a typewriter in every office and many homes decided on balance, they didn't need to. Right? And that means that somebody sat down in a room and thought about it and said we got auto-correct. Right. And I'm not criticizing in any way, shape or form. I think every single one of us makes those decisions every day. And we have to make fewer of them. And we have to be open and aware of what the possibilities for change are. I think the hardest thing is to get up every morning and think, how do we best advance something really novel and maybe a little scary? Because I work so much in nuclear and fission and fusion, I think it's easy to be more afraid than to be excited. Yeah, I feel for the Wright brothers and I feel for folks redesigning hydrogen pipelines. And the question is, how we come up with, with a nod Amos Tversky, the extraordinary Amos Tversky and Danny Khaneman... and how do we get better about behavioral economics? How do we get better at communicating probabilities to human beings? And how do we make more rational and informed decisions sooner? Right. Together.

MARK: Right. All right, great stuff. So what do you think the major roadblocks are in the transition? At this point?

ELISE: I think, I think it's easy for people to talk about the companies. I don't really see that. I really think it's us. I really do. And I think that we have to, it's so clear when we vote with our dollars and with our preferences, how quickly we can transform things. Going from Ma Bell to an iPhone is a non trivial change in human development, right? And human preferences. I think that we have to get better about working together and being less fearful about the new world. And I don't think we have 30 years to do it. That means that we have to get excited about solar on our roofs and we have to get excited about better use of water in our homes. I think if we could change one thing, I would eliminate planned obsolescence. That I think would be most transformational if we could get a government that says to hell with crap, when you buy something that you plug in, it has to work for a generation, right? It has to be, we can no longer afford white good waste, tire waste, all of those things that are readily fungible, fast fashion, all of that stuff should have a significant tax associated with it. And then, can you imagine you would start to focus on the companies that actually do more with less make better product. I think when people join my team, I make them spend an hour at least with en-Roads. If you haven't done Mit's en-Roads, if you haven't taken the time to simulate and solve climate change for yourself, what you really see when you work in en-Roads is that it is an entire economy contribution. That it's not just about electrons or just about fuels, or just about food, or just about carbon capture utilization and sequestration. And I think if you start to see that, then you start to look around yourself and say, okay, I'm not going to use plastics anymore, okay, I am going to work to reduce my footprint. Okay, I'm going to make sure that I demand better products that are more efficient. And as you start to make those decisions, I think you really start to see amplification around change.

MARK: Right. Right. So what do you think are the most important things our students should take away from this discussion?

ELISE: I think they are at this extraordinary moment, I can liken it only to the 1920s and the beginnings of the automotive and age of flight, the 1970s and late '60s and '70s. And really the publicity around space travel and the beginnings of the computing age, right? We are in this transformational age around our impacts and reducing our impacts in a way that allows us to have more equitable, more functional, longer lived prosperity. And I believe that every person's thought needs to be, to come into play -- if you have a great idea, I don't care whether it's B to B or B to C, business to business or business to consumer. I don't care whether it's in food, fuel, electrons; I don't care whether it's on the policy side, the money side or the technology side. We need every great brain thinking about how to do this better. And I believe in this economy, there is a place for everybody to be able to, on the basis of excellence, advance reasonably, and that there's an open possibility to really change the world around you. And Mark, you know, I don't know where you're from, but like again, I'm a small, middle-aged Italian woman. Right. And I was to some degree, the first in my generation of families to go to private school, to be able to be a lawyer, to go get my MBA, to work in a highly technical field. And I know there's a tendency to focus on barriers...and the best advice that I can give is to the extent that you can... recognizing that economics matter, experience matters, and role models matter. They all matter. And we agree. I'm not trivializing how high the burdens are, but I think if you can every morning, sort of ignore all of the barriers and get up with that belief that the world is your oyster, as they say, I'm vegan, I don't particularly like that metaphor. But if you could say I'm going to look at the world and ignore the barriers that I think... being a little hard-headed, being a little resilient, being a little immune to criticism and limits is the best advice that I can give anybody. And forge ahead.

MARK: Really appreciate that. Anything else you'd like to add, Elise?

MARK: No, I always say the same thing, which is where you and I are always happy to talk with anybody who wants to make their way forward in this space. They can reach out to you, they can Google and find me. Our mission and obligation is to be able to enable the next generation. And that's when I say obligation, I really mean obligation. Folks should treat us as ready, willing, and able to spend the time to talk. We welcome that.

MARK: Yes, exactly. Thank you for that, Elise, and really, really appreciate your time today. Thank you.

ELISE: It's an honor and a pleasure. Be well. Thank you.

- M.G. Morgan, et al., "The U.S. Electric Power Sector and Climate Change Mitigation," Section II (pp. 20-26) [3]

- Business Week, "Debt and Equity Financing" [4] (This is an article that is geared more towards small businesses but has good concise definitions of "debt" and "equity.")

- G. Krellenstien, "Transmission Financing" [5] (This presentation presents a clear and frank look at the world of financing energy projects.)

- A primer on "Project Finance" [6] written by HSBC.

- In Canvas, registered students can access the following: Groobey, C, et al. (2010). Project Finance Primer for Renewable Energy and Clean Tech Projects. Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati Professional Corp.

What is due for Lesson 3?

This lesson will take us one week to complete. Please refer to the Course Calendar for specific due dates. Specific directions for the assignment below can be found within this lesson.

- Complete all assigned readings and viewings for Lesson 3

- Project work: Preliminary Project Charter

- Project work: Preliminary Stakeholder Register

Questions?

If you have any questions, please post them to our Questions? discussion forum (not email). I will not be reviewing these. I encourage you to work as a cohort in that space. If you do require assistance, please reach out to me directly after you have worked with your cohort --- I am always happy to get on a one-on-one call, or even better, with a group of you.

Financing Investment Projects: An Introduction

Financing Investment Projects: An Introduction

A lot of what we will be studying in this lesson falls under the umbrella of "corporate finance," even though our focus is actually individual energy projects, not necessarily the companies that undertake those projects. Still, there are a number of parallels and many concepts of how companies should finance their various activities are immediately relevant to the analysis of individual projects. After all, like companies as a whole, individual projects have capital, staffing, and other costs that need to be met somehow. And a company can sometimes be viewed as simply a portfolio of project activities. Similarly, an individual project can be viewed as being equivalent to a company with one single activity. (Following deregulation in the 1990s, a number of major energy projects, such as power plants, were actually set up as individual corporate entities under a larger "holding company.") A lot of the emphasis in the corporate finance field is how companies should finance their various activities. (For example, in the readings and external references, you will see a lot of mention of "target" financial structures.) That isn't really our focus - we are more concerned with understanding the various options that might be available to finance project activities. The "right" financing portfolio is ultimately up to the individuals or companies making those project investment decisions.

Project financing options are numerous and sometimes labyrinthine. You may not be surprised that lawyers play an active and necessary role (sometimes the most active role) in structuring financial portfolios for a project or even an entire company. While individual finance instruments span the range of complexities, the basics are not that difficult. For an overview, let's go back to the fundamental accounting identity:

The balance sheet for any company or individual project must obey this simple equation. So, if an individual or company wants to undertake an investment project (i.e., to increase the assets in its portfolio), then it needs some way to pay for these assets. Remembering the fundamental accounting identity, if Assets increase, then some combination of Liabilities and Owner Equity must increase by the same dollar amount. Herein lies the fundamental tenet of all corporate and project finance: financing activities that increase the magnitude of Assets must be undertaken through the encumbrance of more debt (which increases total Liabilities) or through the engagement of project partners with an ownership stake (which increases total Owner Equity).

Hence, all projects must be financed through some combination of "debt" (basically long-term loans by parties with no direct stake in the project other than the desire to be paid back) and "equity" (infusions of capital in exchange for an ownership stake or share in the project's revenues).

The following video introduces debt and equity in a little more detail. The article from Business Week [4], while it goes more into the specifics for small businesses than our purposes require, also has a nice overview of debt and equity concepts.

Video: Debt and Equity Financing (4:51)

MATT ALANIS: Welcome to Alanis Business Academy. I'm Matt Alanis. And this is an introduction to debt and equity financing.

Finance is the function responsible for identifying the firm's best sources of funding, as well as how to best use those funds. These funds allow firms to meet payroll obligations, repay long-term loans, pay taxes, and purchase equipment, among other things. Although many different methods of financing exist, we classify them under two categories, debt financing and equity financing.

To address why firms have two main sources of funding, we have to take a look at the accounting equation. The accounting equation states that assets equal liabilities plus owner's equity. This equation remains constant, because firms look to debt, also known as liabilities, or investor money, also known as owner's equity, to run operation.

Now let's discuss some of the characteristics of debt financing. Debt financing is long-term borrowing provided by non-owners, meaning individuals or other firms that do not have an ownership stake in the company. Debt financing commonly takes the form of taking out loans and selling corporate bonds. For more information on bonds, select the link above to access the video "How Bonds Work." Using debt financing provides several benefits to firms. First, interest payments are tax deductible. Just like the interest on a mortgage loan is tax-deductible for homeowners, firms can reduce their taxable income if they pay interest on loans. Although the deduction doesn't entirely offset the interest payments, it at least lessens the financial impact of raising money through debt financing. Another benefit to debt financing is that firms utilizing this form of financing are not required to publicly disclose of their plans as a condition of funding. This allows firms to maintain some degree of secrecy so that competitors are not made aware of their future plans. The last benefit of debt financing that we'll discuss is that it avoids what is referred to as the dilution of ownership. We'll talk more about the dilution of ownership when we discuss equity financing.

Although debt financing certainly has its advantages, like all things, there are some negative sides to raising money through debt financing. The first disadvantage is that a firm that uses debt financing is committing to make fixed payments, which include interest. This decreases a firm's cash flow. Firms that rely heavily on debt financing can run into cash flow problems that can jeopardize their financial stability. The next disadvantage to debt financing is that loans may come with certain restrictions. These restrictions can include things like collateral, which require a firm to pledge an asset against the loan. If the firm defaults on payments, then the issuer can seize the asset and sell it to recover their investment. Another restriction is what's known as a covenant. Covenants are stipulations, or terms, placed on the loan that the firm must adhere to as a condition of the loan. Covenants can include restrictions on additional funding, as well as restrictions on paying dividends.

Now that we've reviewed the different characteristics of debt financing, let's discuss equity financing. Equity financing involves acquiring funds from owners, who are also known as shareholders. Equity financing commonly involves the issuance of common stock in public and secondary offerings or the use of retained earnings. For information on common stock, select the link above to access the video "Common and Preferred Stock." A benefit of using equity financing is the flexibility that it provides over debt finance. Equity financing does not come with the same collateral and covenants that can be imposed with debt financing. Another benefit to equity financing is that it does not increase a firm's risk of default like debt financing does. A firm that utilizes equity financing does not pay interest. And although many firms pay dividends to their investors, they are under no obligation to do so.

The downside to equity financing is that it produces no tax benefits and dilutes the ownership of existing shareholders. Dilution of ownership means that existing shareholders' percentage of ownership decreases as the firm decides to issue additional shares. For example, let's say that you own 50 shares of ABC Company. And there are 200 shares outstanding. This means that you hold a 25% stake in ABC Company. With such a large percentage of ownership, you certainly have the power to affect decision making. In order to raise additional funding, ABC Company decides to issue 200 additional shares. You still hold the same 50 shares in the company. But now there are 400 shares outstanding, which means you now hold a 12 and 1/2% stake in the company. Thus, your ownership has been diluted due to the issuance of additional shares. A prime example of the dilution of ownership occurred in the mid-2000s when Facebook co-founder Eduardo Saverin had his ownership stake reduced by the issuance of additional shares.

This has been an introduction to debt and equity financing. For access to additional videos on finance, be sure to subscribe to Alanis Business Academy. And also remember to Like and Share this video with your friends. Thanks for watching.

Debt and equity each have costs. The cost of debt is pretty explicit - lenders typically charge interest. The cost of equity is a little more complex since it represents an "opportunity cost." If an equity investor (like a potential holder of stock) buys into Acme PowerGen Amalgamated, that investor is foregoing the returns that it could have earned from some other investment vehicle. The attitude of most investors, in the immortal words of Frank Zappa, is "we're only in it for the money." Those foregone returns represent the opportunity cost of investing in Acme PowerGen Amalgamated. If we weight these costs by the proportion of some project that is financed through debt and equity means, we have a number that is known as the "weighted average cost of capital" or WACC. The general equation for WACC is:

Here, the "costs" are generally in terms of interest rates or rates of return. So, a company facing a 5% annual interest rate would have a "cost of debt" equal to 5% or 0.05. We'll get into these pieces in more depth, and will explain the strange tax term in the WACC equation after we gain more of an understanding of debt and equity, and how the costs of debt and equity might be determined.

Equity Financing

Equity Financing

The term "equity" in corporate or project finance jargon indicates some share of ownership in a company or project - i.e., some level of entitlement to some slice of the revenues brought in by the company or project. There are different priority levels of this entitlement - typically operating costs must be paid (including, in some cases borrowing costs) before equity investors can get their slice of the net revenues. There are also multiple priority levels of equity investors, which determines who gets paid first if profits are scarce.

The simplest, and one of the most common, forms of equity ownership is through the ownership of company stock. A share of stock is simply an ownership right to a portion of the company's profits. When public stock is initially issued by a company (called an "initial public offering"), the price paid for that stock is effectively a capital infusion for the company.

When you think about shares of stock, you may have in your mind things that are traded on the New York Stock Exchange. Not all stock is traded or issued this way, at least not initially. Often, company founders or owners will decide to sell limited amounts of stock in a company without that stock being available for the general public to purchase or being traded on an exchange like the New York Stock Exchange. A company that issues stock in this way is often referred to as being a "private" company, which means that its stock is held and traded (if it's ever traded) in the hands of individuals or institutions selected by the company. Often times, stock in a private company comes with some sort of voting right or other representation into how the company runs its operations.

A company that issues shares of stock to the general public is called a "publicly-traded" or "public" (for short) company. The term "public" in this case should not be confused with ownership by any government or the mission of the company - the term simply refers to the availability of the company's stock. The decision to "go public" is complicated and has costs as well as benefits. The obvious benefit is that issuing public stock is a relatively straightforward way to raise large amounts of capital. Owners of private stock that allow their stock to be sold in the public offering can also make substantial amounts of money if the demand for the stock among the public is high. There are, however, a couple of big down sides. First, issuing more shares of stock effectively dilutes the value of existing shares. If a company has $1 million in profits over a time period and increases the number of shares of stock from 1 million to 2 million, then the earnings per share of the company drops from $1 per share to $0.50 per share over that time period. People are sometimes willing to pay large sums for company stock if they believe that profits will increase in the future. Second, the more equity investors there are (public or private), the larger the loss of control by the company's initial shareholders.

Raising equity capital can happen through a number of different channels. Brief descriptions of a few of the major channels follow:

- Angel investors

are generally individuals who take equity shares in a company when the company is very young. Often times, friends or family are the original "angel" investors. Angels often take very large stakes in projects or companies, which also gives angels substantial control (in many cases) in how those projects or companies are run. - Venture capital firms are partnerships that make investments in start-up companies. The big difference between venture capitalists and angel investors is that venture capital firms typically invest in a large number of different start-up companies or projects, and so are more diversified.

- Institutional investors

represent groups (not individuals) that can invest money in companies or projects. Examples include pension companies, endowments and even universities (interestingly, during the financial crisis in 2008/09, many universities lost billions of dollars when their investments went sour). Sometimes, institutional investors make direct investments on their own, and sometimes they do so as part of venture capital firms. Institutional investors are generally more restrictive in the riskiness of the projects that they can take on than individual venture capitalists or angel investors might be. - Corporate investors

represent companies that buy equity interests in other companies. It is very common for large companies to purchase direct stakes in smaller companies or individual projects. - Tax equity investors

are especially important to renewable energy projects. These investors provide funds to renewable energy companies or projects in exchange for a share of the tax benefits that those companies enjoy through subsidies and incentives (more on these in Lesson 12). This concept may seem a bit odd - if a company is installing solar PV panels and can claim tax credits for those panels, then why not just claim the credits themselves? The answer is that if the solar PV company is small, then either it does not have a large tax liability in the first place and would not benefit as much from the credits; or it may not be sophisticated enough to wind its way through the maze of tax forms necessary to claim the credits. This is where the tax equity investor comes in. Typically, a tax equity investor will purchase an equity stake in a company (a so-called "joint venture") that is about equal to the value of the tax incentives for that particular investor. Only certain types of entities may act as tax equity investors, and these activities are regulated in the U.S. by the Internal Revenue Service (so-called "passive activity" companies [7]).

The "cost of equity" for a project or company represents the return that an equity investor would need in order to judge that project or company a worthwhile investment. Remember that the cost of equity is really an opportunity cost. Individual investors may have their own criteria for judging opportunity cost, and we can't get into their heads all of the time. So, how do we estimate opportunity cost for a particular project or company? The most common framework is to use a framework called the "Capital Asset Pricing Model" (CAPM). Investopedia has a nice introduction to this framework [8]that includes both the intuition and the equations. Here, we will stick mostly to the intuition.

- First, investments in individual projects or companies are risky, and an investor can always put her money into a safe asset. A bank deposit is typically a safe asset. U.S. treasury bonds are also considered to be pretty safe assets, at least historically. So, the return on equity investment needs to be higher than the return on a safe asset.

- But by how much? One approach that investors sometimes take is to look at similar investments (similar projects or companies) to see how these returns have performed relative to the safe asset. This number is called the "risk premium."

- Finally, there is always some correlation between an individual asset and the market as a whole. This correlation is known as the "beta" and is obtained through statistical analysis of individual project or company returns relative to a market index or average. If a company has a high correlation with the overall market, then returns on that company will be subject to all of the volatility of the market as a whole. In this case, the "beta" for that company would be high, and the cost of equity would also be high.

Using the CAPM to determine the cost of equity, the equation is:

For project evaluation, it is common to use the beta and risk premium relevant to the industry in which the project is going to operate (e.g., utilities for a power plant or gasoline for a refinery). This web page has a nice table estimating the cost of equity for different industries [9].

Debt Financing

Debt Financing

Debt financing refers to capital infusions by entities that do not take any ownership or equity stake in the company or project. Debt financing is like a loan - in fact, bank loans are among the most common forms of debt financing for projects and companies. Most debt is "private," in that it is held in the hands of a single entity (like a bank) or group of entities, and transferring that debt to another party is time-consuming. Just as with stocks, there is "public" debt that is traded openly. Many corporations issue various types of bonds that can be traded no differently than stocks.

The big difference between debt and equity financing has to do with repayment. Equity financing is essentially a loan that is "repaid" through entitlements to a stream of future company or project profits. Debt financing involves various terms of repayment. In many cases, holders of debt have priority on repayment before holders of equity interests in a company.

The cost of debt is determined primarily by how likely or unlikely the lender is to be paid back. If a project goes into bankruptcy, for example, holders of debt may not earn back their entire investments. (One of the advantages of being a lender is that in the case of bankruptcy, lenders often have a higher priority for repayment than equity shareholders.) Rating agencies such as Moody's, S&P, and Fitch use ratings as a general indication of the riskiness of debt.

Wikipedia has nice overview tables and charts [10]of what the various ratings mean. For our purposes, the long-term column is more important than the short-term column. The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis [11] is a nice resource for finding returns or "yields" on corporate bonds of various grades. Often times, for each step away from the top rating (AAA, for example), investors demand a roughly 0.25% to 0.5% increase in yield in exchange for that increased risk of default, but this is not always the case. (You may see examples when you click on different links for corporate bond return data.) The list of available corporate bond rates from the St. Louis Fed can be dizzying. If you search on the website for the bond grade that you're looking for (like "AAA" or "BB") then you can find information more easily. You can also try using a web search engine by typing in "FRED AAA Corporate bond yield" if you were looking for the AAA bond. A couple of specific examples that you can look at to compare yields are:

- AA Corporate Bond Yield [12]

- BBB Corporate Bond Yield [13]

- CCC Corporate Bond Yield [14] (remember, this means "high yield" but also "high risk"!)

Weighted Average Cost of Capital

Weighted Average Cost of Capital

Now that we've covered the basics of equity and debt financing, we can return to the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC). Recall the WACC equation from the beginning of the lesson:

Evaluating the WACC for a company is different than evaluating the WACC for an individual energy project. When the WACC for a company is evaluated, we are often trying to determine (under imperfect information) what a company's costs of capital are. In this case, we would utilize as much financial data as possible in order to estimate the various terms in the WACC equation.

For an individual energy project, the various terms in the WACC equation are determined in large part by the type of investment being made, the type of market (regulated versus deregulated) in which the investment is occurring and the individual company or group of companies making the investments.

The tax rate term in the WACC equation may seem odd. Why discount the tax rate from the cost of debt financing? The reason is that from the perspective of a company, the interest on debt (i.e., the cost of debt) is tax-deductible, so interest payments are offset by tax savings.

Let's go through a hypothetical example to see how this works. Suppose that Mark Linguine PetroServices Amalgamated wanted to invest in a new oil refinery. What is the discount rate that Mark Linguine PetroServices should use in evaluating the NPV of the refinery project? The answer is that the discount rate is equal to the firm's Weighted Average Cost of Capital! So we need to calculate the WACC to determine the discount rate that Mark Linguine PetroServices should use.

Let's assume that 15% of Mark Linguine PetroServices' refinery activity would be financed by debt (just to use a single number). Oil company bonds have historically had very high ratings, so we'll assume that Mark Linguine PetroServices has a long-term bond rating of AAA. Looking online at corporate bond yields [15], we see that a 20-year AAA corporate bond would have a yield of 2.5% (as of the time of this writing - keep in mind that these rates can and do change frequently).

If Mark Linguine PetroServices faced a 35% marginal tax rate, then its cost of debt financing would be 0.025 × (1-0.35) = 0.02, or 2% (I'm rounding up here - the answer to more significant digits is 1.6%).

Turning now to the cost of equity financing, we need the return on the safe asset; the market risk premium; and the beta for the petroleum industry. The yield on the 30-year treasury bond [16] was 2.34% at the time of this writing. We will assume a risk premium of 5%, and from the "Cost of Capital by Sector [9]" web page we see that the beta for the petroleum industry is between 1.30 and 1.45 (the beta is in the second column of the table; we'll use 1.45 for this example). Thus, the cost of equity for Mark Linguine PetroServices would be 0.0234 + (1.45 × 0.05) = 0.1, or 10% (Again, I'm rounding here - the answer to more significant digits is 9.59%).

Assuming that 15% of the refinery was financed through debt and 85% through equity, the WACC for the Mark Linguine PetroServices refinery project would be:

The WACC represents the discount rate that a company should use in conducting a discounted cash flow analysis of a given energy project. The reason is that the discount rate represents the opportunity cost of getting something in the future relative to getting something today. Since the WACC represents the average return for an energy project (remembering that that average is weighted across both debt and equity investors), it represents a kind of average opportunity cost for investment in a project.

Market Deregulation and the Cost of Capital

Market Deregulation and the Cost of Capital

Please read Section II (Problems in Managing the Restructured Industry) from Morgan, et al. [17] and have a look at the presentation from Gary Krellenstein [5]. Krellenstein's presentation in particular, while focused mostly on transmission investment, raises a number of really important issues regarding how changes in market institutions - such as decontrols on wellhead prices for natural gas, or electricity deregulation - have changed the investment environment for large energy projects. These impacts have perhaps been most evident in electricity, but are not confined to just the electricity sector.

The main idea from both readings is that deregulation has done two things simultaneously. First, it has removed the guarantee of cost recovery from major energy projects such as power plants. (Krellenstein's presentation is focused on transmission because, at the time that it was written, the U.S. federal government was considering proposals to deregulate transmission the same way that it had deregulated generation. In the end, it did not, and most transmission lines continue to enjoy cost recovery ensured by the state or federal government.) This means that energy projects need to earn sufficient revenues to cover costs, plus meet the rate of return demanded by investors. Second, commodity prices in deregulated energy markets are volatile - we have seen this in previous lessons with oil, petroleum products, natural gas, and electricity. Since the revenue stream for energy projects became more volatile, the projects themselves are viewed as being increasingly risky.

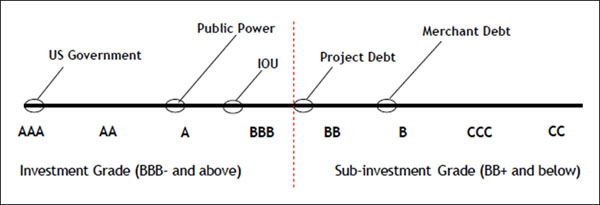

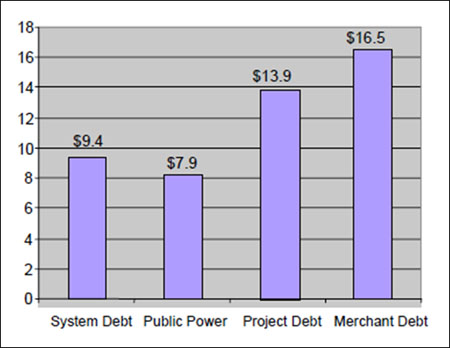

The point that Krellenstein makes on slide 13 of his presentation about "system" versus "project" financing sums it up nicely. From an investor's point of view, regulated energy markets are safe because the risks of cost recovery are effectively shifted from the project's owners to the people who pay energy bills. This may not be economically efficient, but from capital's point of view it is safe. Deregulation has shifted some of this risk back to the project's owners (i.e., the company building/operating the plant and its equity shareholders). This is why Krellenstein points out that the majority of "project financed" energy investments are heavily weighted towards debt financing. Since this debt financing is not highly rated (see Figure 3.1, from Krellenstein's presentation), it carries higher yields. The equity component of that financing also becomes more expensive since investors demand returns over a shorter time horizon, as shown in Figure 3.2 (also from Krellenstein).

Project Finance

Project Finance

Project Finance is the funding of a specific project or group of projects (like a PV Solar electricity generation project) on a non-recourse basis through a special purpose entity. What does that exactly mean?

- The lenders to the project do not have access to the assets of the corporation, but only the assets of the project if the project defaults (non-recourse).

- There is a special purpose entity (SPE) set up to construct, operate and maintain the project(s). This SPE is responsible to also distribute the funds from operations such as expenses, taxes, debt service and returns to equity through the life of the project.

Why do we use project finance?

- Lower financing costs.

Because debt is cheaper than equity and a project financed structure can use more debt the overall cost of capital is lower. This makes the project have a higher return. To convince yourself of the benefits of leverage go to this simplified model. Play around with the debt percentages in cells d2 and g2. This shows how higher debt levels can increase returns to equity shareholders. Also please note that above a certain level of debt, the model does not compute a return. This is because, at a certain level of debt, lenders become less willing to capitalize projects if developers do not have some “skin in the game” (bear some risk). You will also see that the interest rate increases on the debt as the leverage goes up. Why do you think the interest on the debt would increase as the leverage increases? - Enforces discipline on how the project is developed and managed.

Because the debt is tied to a specific project, the project developers are required to spend the capital and manage the project subject to covenants agreed to by the lender and developer. - Allows greater investment in worthy projects.

By providing for the financing off the balance sheet and therefore not breaching its corporate debt covenants or other constraints, the developer can raise most of the funds to capitalize the project based on the projected cash flows of the project.

Lesson 3 Summary and Final Tasks

Summary and Final Task

In this lesson, we took closer look at the process of raising capital, from venture capital to stocks to bonds. The world of corporate finance can get very murky very fast; and, in some ways, it's more of a legal practice than a business practice. Our focus was on understanding the various mechanisms that are used to finance energy projects and the implications of those funding mechanisms on overall project costs.

When we are looking at social decisions that involve common costs and benefits, the discount rate is usually more of a matter of debate than anything else. But when a business decision is involved (and that business is a for-profit entity), then there is a rhyme and reason behind the determination of the discount rate as the "opportunity cost" of its investors. There are many different types of investors in a typical firm or project, all of whom face different opportunity costs, so we will encapsulate these in a single number called the "weighted average cost of capital" (WACC). The WACC turns out to be the correct discount rate for a company or a project.

Reminder - Complete all of the Lesson 3 tasks!

You have reached the end of Lesson 3! Double-check the What is Due for Lesson 3? list on the first page of this lesson to make sure you have completed all of the activities listed there before you begin Lesson 4.