Learning Objectives Self-Check

Read through the following statements/questions. You should be able to answer all of these after reading through the content on this page. I suggest writing or typing out your answers, but if nothing else, say them out loud to yourself.

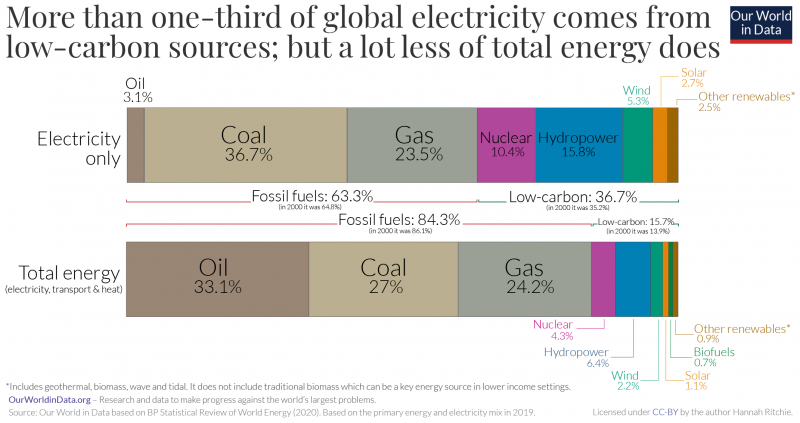

Nuclear energy has been a hot-button issue for a very long time, both domestically and internationally. It provides about 10% of the global electricity supply, as you can see in the image below.

Supply

As you (hopefully) recall from Lesson 1, nuclear energy is non-renewable. Uranium is by far the most-used nuclear fuel, though there are possible alternatives (such as thorium). As with other non-renewable fuels, all of the uranium that is on earth now is all that we will ever have, and estimates can be made of the remaining recoverable resources. As you will see in the article below, at current rates of consumption, we will not run out of uranium any time soon. But - at risk of sounding like a broken record - this highly depends on a number of variables, including keeping consumption at current levels, technology not advancing, estimates of reserves changing, and so forth. If, for example, we waved a magic wand and doubled the output of nuclear power tomorrow, the estimated reserves would last half as long.

The World Nuclear Association (WNA), an industry association, provides a very thorough explanation of possible complicating factors, but they state that at current rates of consumption, as of the fall of 2021 the world has enough reserves to last about 90 years. The Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA), like the WNA, is effectively an industry group and has a wealth of expertise at its disposal. It operates out of the OECD (remember them from Lesson 1?) in Paris. They are a pro-nuclear group but are very good at providing technical data, as well as statistics. They indicate that as of 2018, the world had about a 130 year supply of uranium.

Optional Reading

The author of the article below provides a number of reasons why nuclear energy will not play a large role in the global energy future.

- "Why nuclear power will never supply the world's energy needs." Lisa Zyga, phys.org.

Feasibility

The first nuclear power plant came online in 1954 in Russia (then the Soviet Union), and according to the World Nuclear Association, there are 436 reactors worldwide and another 59 under construction. The technology is well-known by now, and despite the extreme danger posed by nuclear meltdowns, there have been very few major incidents. You are probably familiar with the Fukushima Daichi meltdown that happened in 2011, and perhaps heard of Chernobyl in the Ukraine in 1986 (still the worst nuclear disaster to date), and maybe even Three Mile Island in the U.S. in 1978. Here is a partial list of nuclear accidents in history from the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS).

But putting aside this risk at the moment, nuclear energy has shown itself to be a viable source of electricity, and likely will continue to be used for the foreseeable future. Among other things, nuclear power plants generally have a useful lifetime of around 40-60 years, so we are "locked in" until mid-century at least. That said, increasing the use of today's nuclear technology would likely pose some problems, for a variety of reasons. The article below sums up these and a few others reasons for and against nuclear energy.

Sustainability Issues

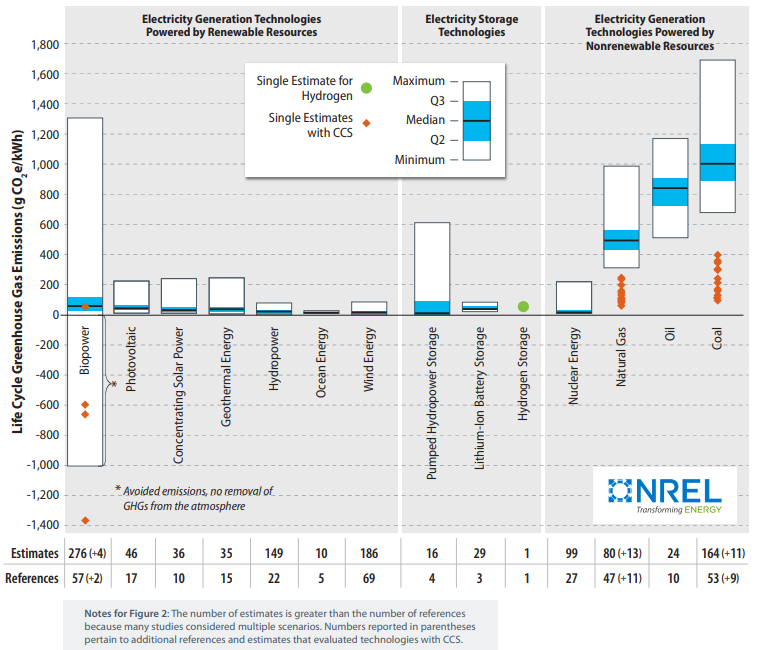

Okay, now for the fun part. Nuclear energy is a mixed bag in terms of the question of sustainability. The biggest dilemma for those concerned about anthropogenic climate change but skeptical of nuclear is that nuclear energy is considered a carbon-free source, and since it is responsible for a significant portion of non-fossil fuel based electricity production worldwide and is a proven and reliable source, it is seen by many as a good option. Note that despite being considered "carbon free," nuclear energy results in some lifecycle emissions because of the materials used in mining, building the power plant, and so forth. (Lifecycle emissions are all the emissions generated by all processes required to make an energy source, including things like mining of materials, manufacturing of equipment, and operating equipment.) But according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), a U.S. National Lab, it has approximately the same lifecycle emissions as renewable energy sources.

Nuclear energy is a very reliable source of electricity, and power plants can operate at near full capacity consistently. Once a plant is built, electricity is relatively inexpensive to generate. But nuclear energy is very expensive in terms of lifetime costs (as you'll see in the article below), and the waste from nuclear reactors can remain dangerous for thousands of years, which can result in large externalities. Since they are so expensive, there is an incentive to keep a plant online for as long as possible to recoup costs, thus people are effectively "locked in" once a plant is built. There is, of course, the risk of another disaster, which however rare the possibility, could be catastrophic. There are also some issues with the equity impacts of uranium, particularly in terms of mining. There is not an easy answer here, as there are reasonable and strong pros and cons.

To Read Now

The first article below is a good example of why it pays to pay attention to citations and be well-informed on a topic, in regards to finding good information sources. The article is on a website that I've never heard of before, so at first, I was suspicious of the content. However, they provide legitimate sources for the information presented, and I have enough prior knowledge to know that the arguments they put forth are legitimate. Overall, it's a good summary of some of the pros and cons of nuclear energy, though I have a few minor issues with the content, as I'll describe below. (See if you can figure out what I take issue with.)

- "Pros and Cons of Nuclear Energy." UnderstandSolar.com

- (Optional) "Unable to Compete on Price, Nuclear Power on the Decline in the U.S." Brian Mann, PRI.

- (Optional) "Nuclear, Carbon Free but Not of Unease." Henry Fountain, New York Times.

- (Optional) "Nuclear Power Prevents More Deaths Than It Causes." Mark Schrope, Chemical, and Engineering News.

Did you guess the issues I have with the first article? First, the author calls nuclear a very "efficient" energy source. If you recall from previous lessons, the efficiency of a nuclear power plant hovers around 35%. It is, however, energy dense (a lot of energy by volume), which is what he describes as "efficient." (Though he also mentions energy density as well, confusingly.) The second - and more subtle - problem I have is with the assertion that nuclear is an "inexpensive" energy source. This was clearly indicated in the second article (if you read it) but is also asserted by the EIA. Nuclear plants are inexpensive to run once they are built, but they are extremely expensive to build. The author glosses over that part, but it is a really important consideration. Finally, he says that nuclear is "sustainable" but as you know by now, any energy source that is non-renewable is not sustainable.

Regarding the cost of nuclear: The high up-front cost makes nuclear power one of the most expensive types of electricity available. For a technical discussion of this, feel free to read through this description of levelized cost of electricity from the EIA, which indicates that over the lifetime of the energy source, nuclear is more expensive than geothermal, onshore wind, solar, hydroelectric, and most types of natural gas plants.

Summary

Nuclear is a mixed bag. To summarize:

- Nuclear is reliable and almost carbon-free, but is non-renewable.

- Nuclear is relatively inexpensive to operate after established, but the high up-front cost makes it one of the most expensive electicity sources.

- Because power plants are so expensive to build, once they are built they are generally used for as long as possible, as long as they can be operated profitably. (Gotta get that investment back!) We are effectively "locked in" once they are built.

- When accidents happen, they can be catastrophic, but they are extremely rare.

- The waste product from nuclear power plants is dangerous for thousands of years, and right now we have no way of safely disposing of it - it is kept in storage, usually at the power plants themselves. This has not shown to be a major problem yet, but society will be dealing with the wastes for thousands of years.

Nuclear is a very controversial source of energy. It is embraced by many as a key to the a carbon-free future, while many think we should move away from it because of its inherent danger and/or expense and/or general sustainability problems. There are arguments to be made on each side. Hopefully, you have a better handle on some of them after reading through this.

Check Your Understanding

Why are we "locked in" to the use of nuclear energy once a plant is built?

Optional (But Strongly Suggested)

Now that you have completed the content, I suggest going through the Learning Objectives Self-Check list at the top of the page.