Lessons

Lesson 1: Solar and Anaerobic Digestion

Overview

In this lesson, we'll go over solar and anaerobic digestion in a little more detail. We will see some of this in our travels, and I want you to have a better understanding of some of the basics.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- identify different types of solar technologies;

- explain the basic process by which solar panels generate electricity;

- explain the difference between irradiance and irradiation;

- calculate energy use/generation given power and time;

- evaluate the impact of tilt and orientation on solar PV output;

- calculate the output of a solar array;

- explain how anaerobic digestion converts organic material to biogas; and

- identify some of the benefits of anaerobic digestion.

Lesson Roadmap

| To Read | Lesson 6 Online Content | You're here! |

|---|---|---|

| To Do |

|

|

Questions?

If you have any general course questions, please post them to our HAVE A QUESTION discussion forum located under the Discussions tab in Canvas. I will check that discussion forum regularly to respond as appropriate. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses and comments if you are able to help out a classmate. If you have a question but would like to remain anonymous to the other students, email me through Canvas.

If you have something related to the material that you'd like to share, feel free to post to the Coffee Shop forum, also under the Discussions tab in Canvas.

Solar Energy

As was detailed in an earlier lesson, solar energy is electromagnetic (aka radiant) energy that is generated by the (nuclear) fusion of hydrogen atoms into helium atoms in the sun. The amount of radiant energy that is released by an object is related to its temperature, and since the sun is so hot (~10,000º F!) [1], it is able to reach the ~94,000,000 miles (the distance depends on the time of year) to the earth. It is a massive amount of energy! A commonly cited statistic is that enough solar energy reaches the earth each hour to provide all of humanity's energy for an entire year. There is no shortage of solar energy.

Types of Solar Energy Technologies

Without the sun, life on earth would not be possible. It provides energy for vegetation to grow and provides sufficient heat to allow water to exist in liquid form, among other things. But there are many ways that humans can use this radiant energy more deliberately. The following is an overview of the major types of solar technologies. We could spend weeks analyzing each of these - keep in mind that this is just an overview.

- Solar photovoltaics (solar PV): Certain materials have the natural property of converting energy from the sun into electricity. When the sun hits these materials, electrons start to flow, creating a direct current (DC). This is the photovoltaic effect. This is described in more detail below.

- Solar thermal: This is a broad term for systems that use energy from the sun to heat water (or other material) for a variety of purposes. One common application is heating water for domestic hot water or swimming pools.

- Concentrated solar: There are a variety of ways to concentrate solar power for use. All of them gather solar energy over a wide area (usually by using mirrors) and concentrating it into a smaller location. This very high level of power is then often used to generate electricity. The DOE has a good explanation of some technologies here [2].

- Passive solar: Passive solar is a type of solar thermal that uses passive system design (e.g. south-facing windows, strategically-placed overhangs) to passively heat interiors of buildings. This is a great low-tech way to use solar energy! (Click here for more information about passive solar from the DOE.) [3]

Solar Photovoltaics and Availability of Solar

The rest of the solar lesson will focus on solar photovoltaics or solar PV. As noted above, photovoltaic technology (aka the photovoltaic effect) converts radiant solar energy into electricity. View the short video below from the U.S. Department of Energy for a brief explanation. Note that the narrator of the video indicates that photons provide the energy that is converted into electricity. NASA describes [4] the relationship between photons and electromagnetic energy thusly: "Electromagnetic radiation can be described in terms of a stream of mass-less particles, called photons [5], each traveling in a wave-like pattern at the speed of light [6]." So photons are generally considered to be what carries the energy that is emitted in waves.

All right, we all know that the sun's energy creates heat in light, but it can also be converted to make electricity, and lots of it. One technology is called solar photovoltaics or PV for short. You've probably seen PV panels around for years, but recent advancements have greatly improved their efficiency and electrical output. Enough energy from the sun hits the earth every hour to power the planet for an entire year. Here's how it works.

You see, sunlight is made up of tiny packets of energy called photons. These photons radiate out from the Sun and about 93 million miles later, they collide with a semiconductor on a solar panel here on earth. It all happens at the speed of light. Take a closer look and you can see the panel is made up of several individual cells, each with a positive and a negative layer, which create an electric field. It works something like a battery, so the photons strike the cell and their energy frees some electrons in the semiconductor material. The electrons create an electric current which is harnessed by wires connected to the positive and negative sides of the cell. The electricity created is multiplied by the number of cells in each panel and the number of panels in each solar array. Combined, a solar array can make a lot of electricity for your home or business. this rooftop solar array powers this home, and the array on top of this warehouse creates enough electricity for about a thousand homes.

Okay, there are some obvious advantages to solar PV technology. It produces clean energy. It has no emissions, no moving parts, it doesn't make any noise, and it doesn't need water or fossil fuels to produce power. And it can be located right where the power is needed, in the middle of nowhere, or it can be tied into the power grid. Solar PV is growing fast and it can play a big role in America's clean energy economy anywhere the sun shines.

Okay, so a solar panel converts radiant to electrical energy by using the unique properties of a semiconductor, usually, silicon combined (doped) with other elements (usually boron and phosphorous). But how much energy and power does a panel generate? As you might guess, it depends on a lot of factors. The following is an overview of some of these factors.

- First, a quick primer on power vs. energy.

- Energy is the ability to do work. It is a discrete amount of "something," and that "something" makes things happen (makes things move, generates sound, generates heat, etc.). If one thing has more energy than another thing, then it is hypothetically capable of doing more "stuff." In the U.S., energy is usually measured in Btus, or if it's electrical energy, kilowatt hours (kWh). One kWh is 1,000 Wh, which is also a unit of energy. The international unit of energy is the Joule (J). Since there are 1,000 Wh in one kWh, to convert Wh to kWh you must divide by 1,000. To convert kWh to Wh, you multiply by 1,000.

- Power is the rate at which energy is converted. Practically speaking, it indicates how quickly you are "using" energy or the rate at which energy is being provided. Power is usually measured in watts (W) or horsepower (HP). A light bulb that uses 100 W of power is converting 100 Joules of electricity into heat and light each second. A 200 W light bulb is converting energy twice as quickly. A 1,000,000 W power plant (1 MW) is providing energy twice as quickly as a 500,000 W (500 kW) power plant. (Note that the light bulbs and power plants are all just converting one form to another, but from our perspective, one is "using" energy and one is "generating" energy. It's a matter of perspective.)

- Energy = power x time. For example:

- If you use a 100 W light bulb for 1 hour, you use (100 W x 1 h = ) 100 Wh.

- If you use a 100 W light bulb for 1 hour each day for a year, you use (100 W x 1 hr/day x 365 days/yr = ) 36,500 Wh = 36.5 kWh.

- If you use 10 light bulbs, each 100 W, for 1 hour you use (10 bulbs x 100 W/bulb x 1 hr = ) 1,000 Wh or 1 kWh.

- If a 5,000 W (5 kW) solar array operates at full capacity for 1 hr, it generates (5,000 W x 1 hr = ) 5,000 Wh or 5 kWh of electricity. This is the energy that is generated by the panels, but some of that energy will be lost by the time it is used.

- If a 1,000,000,000 W (1 GW) power plant operates at full capacity for 24 hours, it would generate (1 GW x 24 hr = ) 24 GWh of electricity.

- If a furnace with a 100,000 Btu/hr output operates at full capacity for 2 hours, it would use (100,000 Btu/hr x 2 hr = ) 200,000 Btu of energy.

- Irradiance is the amount of solar power (not energy) incident on a given surface area at any given time. This is usually measured in Watts per square meter (W/m2). All else being equal, more irradiance results in more output from a panel. Irradiance levels change throughout the day, as you can see in the image below. These charts illustrate the average hourly irradiance in State College, PA in July and December. As you can see, the peak irradiance in July averages about 750 W/m2. This is the irradiance on a horizontal surface. If you could tilt the surface (say, a solar panel) so it is perpendicular to the sun, the noon irradiance would be more than 1,000 W/m2. So if you want to imagine 1,000 W/m2, think of how your skin feels on a really hot summer day at Penn State. Hopefully, this gives you a "feel" for irradiance.

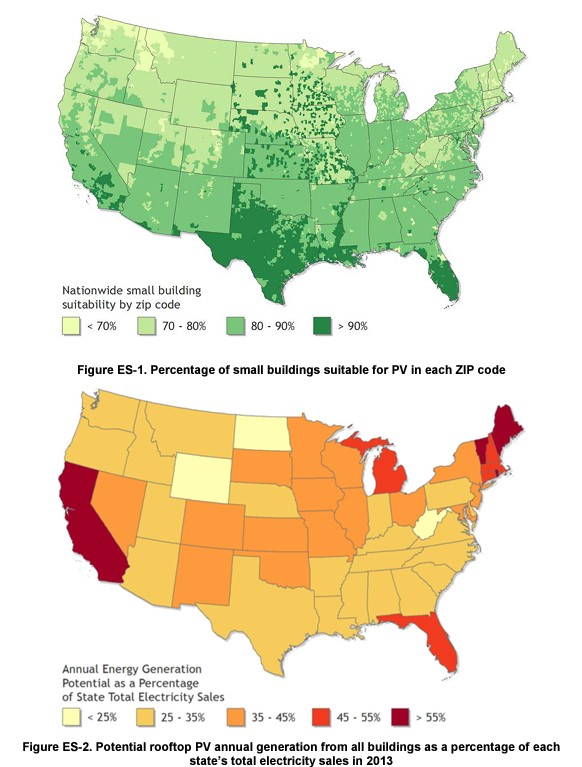

- Irradiation is the amount of solar energy that hits a surface over a given period of time. This is usually measured in kWh/day/m2 or kWh/yr/m2. See the chart below for a map of irradiation in the U.S., which illustrates the average daily irradiation levels throughout the year in the U.S. Of course the irradiation will change throughout the year (more in the summer and less in the winter), but this chart provides a clear idea of the overall amount of solar energy that is available all year. (Note that you could easily find the average annual irradiation by multiplying the daily irradiation by 365.) Keep in mind that this is the average daily irradiation on a surface that is "latitude tilt," which will be explained in more detail below. The chart provides an indication of solar potential. (Note that due to panel inefficiency and a few other factors, a solar panel will only convert a fraction of this solar energy into electricity.)

Solar PV

We will experience some solar PV installations and technology while traveling, so I provide some more details about it below.

- In order to maximize panel output, the panel should be as close to perpendicular to the sun's rays as possible, which allows it to capture the most solar energy possible at a given time. (Here is a really good interactive animation [10] of why a perpendicular panel captures the most sunlight.) Most solar panels are fixed, i.e., they don't move. This means that you need to choose your location carefully. For fixed panels, there are two factors to consider in this regard:

- Azimuth/orientation is the compass direction that the panel faces. Typically, 0º is due north, 90º is east, 180º is south, and 270º is west.

- Tilt is the angle above the horizon to which the panel is tilted.

- Shading is a very important consideration as well. All else being equal, more shading means less output.

- In the Northern Hemisphere, the rule of thumb to maximize the output of a fixed panel is that the panel should be faced due south (180º orientation) and at "latitude tilt." You may recall from a Geography class that latitude is how far north or south a location is from the equator. The equator is 0º, the tropics are at 23.5º, and the North and South Poles are at 90º north and south, respectively.

- For example, State College, PA is at just over 40º north, so the ideal array tilt is about 40º, and the ideal azimuth is 180º (south).

- Anchorage, Alaska is at about 61º north, so the ideal tilt and azimuth are about 61º and 180º (south), respectively.

A few more terms that are important to know:

- A solar cell is the smallest current-generating part of an array. They can be any size but are normally around 6 inches by 6 inches. It's difficult to see, but in the image above there are 72 cells in each panel (12 rows, each with 6 cells).

- A solar panel (aka module) is a number of cells wired together in a single panel. They can be any size but are usually about 5 feet by 3.25 feet [11].

- A solar array is a number of panels wired together. The image above shows part of a solar array, which as I noted has 270 total panels.

- Capacity refers to the rated maximum output of a panel or array. Under optimal conditions, a 250 W panel will output about 250 W of electricity. Note that this is only the immediate output. By the time the electricity goes to the building or the grid, some of it is lost due to a variety of factors (usually 10% - 15%).

- The array above has 270 panels, and each panel has a capacity of 305 W. Thus, the capacity of the array is (305 W x 270 = ) 82,350 W, which is 82.35 kW.

- A solar panel outputs DC (direct current) electricity. DC means that the electricity flows in one direction. Household outlets (and the electric grid) use AC (alternating current) electricity, which rapidly alternates direction of flow (60 times per second in the U.S., in case you are interested), so electricity from an array must be converted to AC if it is to be used in a building or distributed to the grid. An inverter is a piece of equipment that converts DC to AC and is a standard part of most solar arrays.

- A grid-tied array is one that is connected to the grid. A standalone or off-grid system is not tied to the grid.

The Impact of Tilt and Orientation

Recall that the rule of thumb is that the optimal tilt is "latitude tilt," and the ideal orientation in the Northern Hemisphere is due south (180º). This begs the question: what happens if the tilt and orientation are not optimal? The answer, as you might guess, is "it depends." This impact can be quantified by something that is called tilt and orientation factor (TOF). The tilt and orientation factor is a decimal that indicates what percent of the maximum solar output you would receive throughout the year at said tilt and orientation. So if you install an array and it has a TOF of 0.85, that means that it will only be able to output about 85% of the energy it would output if it were at the ideal tilt and orientation.

Wilmington, Delaware is at about 40º north. As it turns out, the ideal tilt is closer to 35º (rules of thumb are only rules of thumb, after all!). The tables below show the TOF at different tilts and azimuths. The first table illustrates the TOFs of different tilts, all with an orientation of 180º. The second table shows the TOFs at different azimuths, all at a tilt of 35º (the ideal tilt).

| Tilt (º) | Azimuth (º) | TOF |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 180 | 0.87 |

| 5 | 180 | 0.905 |

| 10 | 180 | 0.935 |

| 15 | 180 | 0.959 |

| 20 | 180 | 0.978 |

| 25 | 180 | 0.991 |

| 30 | 180 | 0.999 |

| 35 | 180 | 1.0 |

| 40 | 180 | 0.996 |

| 45 | 180 | 0.985 |

| 50 | 180 | 0.969 |

| 55 | 180 | 0.947 |

| 60 | 180 | 0.92 |

| 65 | 180 | 0.888 |

| 70 | 180 | 0.851 |

| 75 | 180 | 0.81 |

| 80 | 180 | 0.764 |

| 85 | 180 | 0.715 |

| 90 | 180 | 0.662 |

| Tilt (º) | Azimuth (º) | TOF |

|---|---|---|

| 35 | 90 | 0.797 |

| 35 | 100 | 0.833 |

| 35 | 110 | 0.897 |

| 35 | 120 | 0.898 |

| 35 | 130 | 0.926 |

| 35 | 140 | 0.951 |

| 35 | 150 | 0.972 |

| 35 | 160 | 0.986 |

| 35 | 170 | 0.996 |

| 35 | 180 | 1.0 |

| 35 | 190 | 0.997 |

| 35 | 200 | 0.989 |

| 35 | 210 | 0.976 |

| 35 | 220 | 0.956 |

| 35 | 230 | 0.932 |

| 35 | 240 | 0.905 |

| 35 | 250 | 0.874 |

| 35 | 260 | 0.839 |

| 35 | 270 | 0.803 |

Calculating Solar Output

Okay, now we're ready to calculate the solar output. There are a number of software programs and a formula or two that can do this, but the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) provides a free one that is well-regarded in the energy industry called PVWatts [12]. In the video below, I demonstrate how to calculate the annual output of the array in the images above, which has the following specs:

- address: 400 Stanton Christiana Rd, Newark, DE

- 82.35 kW capacity

- 13º tilt

- 222º azimuth

Alright so, I'm going to demonstrate how to use the PVWatts Software from NREL. So, here is the home page. You can Google PVWatts and this will come up. And so, first thing you do is you type in the address. So this is based on the array that's detailed on the course website. So my address here is 400 Stanton Christiana Road in Newark. Ok, so you just click enter. And click go. And so, it used to be that it would come up with a map here, but they changed some things about this. So what it does, it just tells you the latitude and longitude of where you are. And so, I just happen to know that this is the right latitude and longitude, so I'm going to click to go to system info here. Ok, and here is where I can enter the specifics of the system. So, you can see the first window here is the DC system size, so this is the capacity. So mine is a 82.35 kW, you notice this is in kW, so be very careful about that. The module type, you have a couple different kinds. This is standard module. The fixed open rack is fixed meaning it's not, it doesn't move so there's no tracking. I mean you could do one to two-axis tracking here. The system losses, this shows you the overall losses from the rated capacity. So, I'm going to click on this loss calculator just to show you some of the variables here.

So this comes up, you can see that here. So right now the estimated system losses are 14%. And you can see that these are the actual, the individual factors in those losses. So soiling meaning you know, dust and stuff that gets on the panel. Shading, so it's assuming there's some shading part of the time. In this case, 3% of the time. You know, is there snow? Is there panel mismatches? Panels have small imperfections so they might have slightly different voltages. So there's wiring losses anytime you run electricity through a wire. There's heat losses. Connections to this is just sort the you know, the connections between the modules and other components. There's some degradation that occurs through panels getting warm, and it's also they just degrade a little bit over time. This name-plate rating there's slight imperfections, you know, the panels are usually guaranteed to be, have this capacity within a certain percentage. And then if they're older, you would actually, panels degrade over time. And the availability just means sometimes the system goes down for repairs or whatever, ok? And so you can actually change this. So like if I said this is in a perfect location without any shading at all I could put zero in here and you notice this drops to 11%. So we'll just go with our standard 14% and then you can click save. Ok? So that's where all the system losses come from. Now you can enter in your total. In this case, I have 13 degrees. Your azimuth, remember, is your also the same as your orientation. This one happens to be 222 degrees.

Ok, so now, you can also add some cost considerations. There's some other parameters you can feel free to mess around with those. In this case, this is actually commercial and I'm just going to, I happen to know our utility rate at our school. It's about 8 cents a kilowatt hour. Ok. Good, good, good.

Now you could also draw the system. Actually, you can't anymore. You used to be able to draw your system on a rooftop using Google Maps, but you can't do that.

Ok, so now we click to go to the results. And, here you go. So based on the system specs that I put in there, I'm going to generate about 106,000 kWh per year. Keep in mind that, you know, it says 106,365. This, you know, you should take this as a round number. You could have a really good solar year. There's a bunch of extra, you know, energy generated. You could have a bad year the system could go down a lot. There's I don't know a bunch of extra moisture and dust in the air, whatever. So this is just a really good estimate. Ok. Yeah, see it even gives you the range here. Based on this location, 101 to 110 kWh per year. So this actually gives you the month to month break down. Ok. So here's your actual output in AC. Remember panels produce DC, so this is AC output. And this is based on the cost information that I put into the specs on the previous sheet. So it's saying that, you know, I would earn about, or save about 8500 dollars a year with this system. Now what's really cool about this, is you can actually download these results. So, you can download this exact information but in spreadsheet form. And you can even download the hourly results which is really cool. I mean you get this Excel spreadsheet with 8,760 rows in it. It tells you the estimated output under normal typical meteorological conditions throughout an average year. So that's pretty cool. And then you can use, you know, make charts and so forth in Excel. Ok, so that's a basic tutorial on how to use PVWatts.

A Few More Notes

Hopefully, by now you have a relatively good grasp on some of the considerations that go into designing and calculating the output of solar PV. Solar PV really took off in the early- to mid-2000s, led by residential array installations, which generally had capacities of a few kW. The solar industry in the U.S. is now dominated by utility-scale solar, which is much cheaper per W to construct because of economies of scale. Utility-scale arrays can be thousands of watts (multiple MWs) in capacity!

There are a few ways that people can use and pay for solar PV:

- Systems can be purchased and owned by individuals. This can be done out-of-pocket or using loans. Out-of-pocket purchases usually generate the highest return.

- Power purchase agreements allow people or businesses to pay a third party to build an installation on their own roof. The individual or business then pays the third party for the electricity generated at a contractually agreed-upon rate. This is the model that SolarCity (now Tesla Energy) used to rise to prominence. This is a popular model because it requires no up-front cost (among other reasons).

- Community-owned solar or just community solar is used increasingly in the U.S. and elsewhere. Community solar allows individuals to "buy into" a solar array that is installed somewhere else, or perhaps on a shared roof or field space. This provides access to individuals and businesses that would not otherwise be able to use solar due to factors such as not having a suitable site (e.g., a heavily shaded roof) or living in rented space. (The SEIA provides a good overview of community solar here [13], and NREL provides a more robust explanation here [14].)

- Most utility-scale installations effectively act as power plants, and the electricity is sold to the grid.

Incentives

Incentives have played a very important role in the growth of the solar industry, and renewable energy in general. The following provides a description of some incentives.

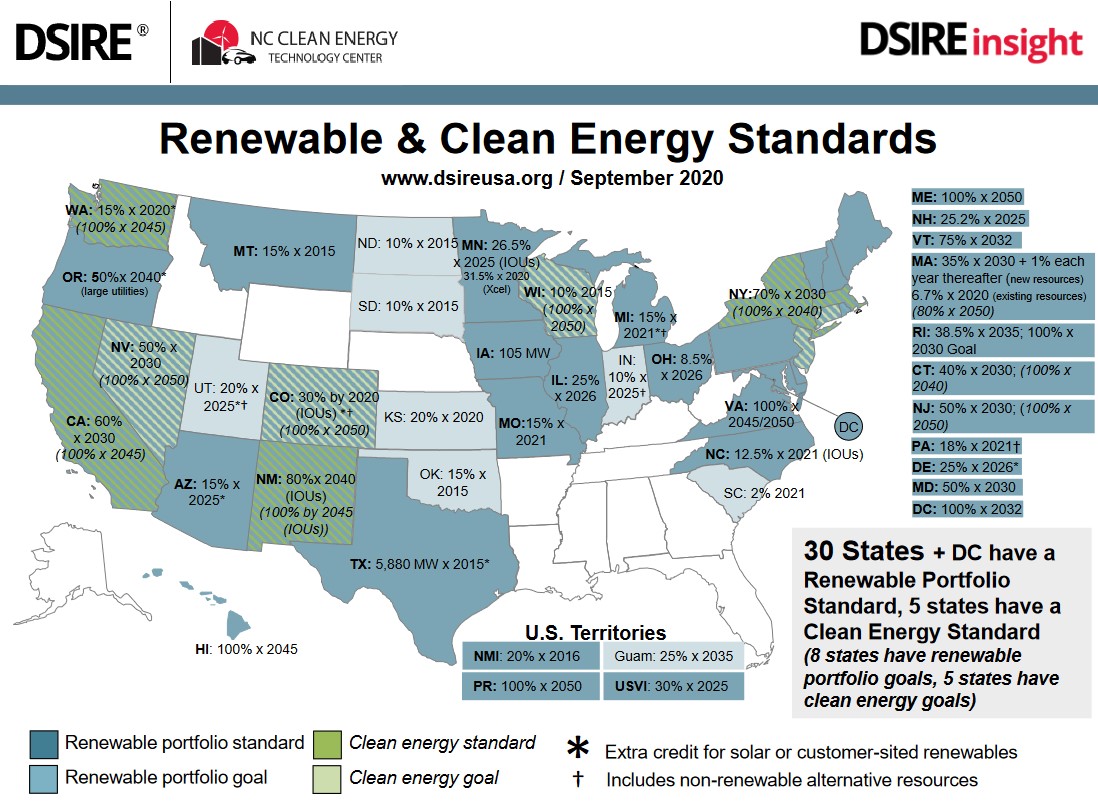

States and countries have implemented a variety of policies meant to incentivize or encourage private investment in clean, renewable energies. The most common of these policies are tax credits, grants/rebates, and performance-based incentives (PBI), including feed-in tariffs (FIT) and renewable portfolio standards (RPS).

A tax credit is just that, a credit. When an individual or business investor earns a tax credit it means that the amount of the credit will be subtracted from a future tax bill. For example, in the United States, we have a Federal Residential Renewable Energy Tax Credit [15] available to the residential (not commercial or industrial) sector which provides a tax credit covering 26% of the cost of an installation. A typical residential system costs about $3/Watt to install. If you put a 7 kW photovoltaic system on your roof, it should cost around $21,000 before incentives (7,000 W x $3/W). If so, you would earn a $5,460 tax credit. The government doesn’t mail you a check for this amount. It means you get to deduct that amount from your next tax payment. To realize this money, you will need to have paid at least $5,460 in taxes, but excess credits can "generally" be carried over to future tax years. Note that even if you were owed a refund, this tax credit can be used to increase your refund, as long as you paid at least $5,460 in federal income tax throughout the year. Other renewable energy technologies qualify for this credit. See the link above for details.

A rebate means that a government agency or other group (sometimes utility companies) will refund some of the investment. These are usually based on the size/capacity of the system. For example, Pennsylvania used to provide a solar rebate program that provided rebates to investors of $1.75/Watt. Rebates are checks mailed directly to the investor (or their designate). Many states still have such programs such this solar PV rebate program in Oregon [16](description from DSIRE of course!). Different states often have different program specifics. See DSIRE for more examples of programs. Specifics vary within states as well. The program in Oregon, for example, has different rebate levels for different utilities and for different sectors (residential, agricultural, industrial, non-profit, government). For example, if you are a residential customer of the PGE utility in Oregon, you would receive $0.25/W up to $1,750. So for a 7 kW system you would recieve a $1,750 (7,000 W x $0.25/W) rebate.

Performance-based incentives (PBIs), also known as production incentives, provide cash payments based on the actual output of the system. For wind and solar electric, this is the number of kilowatt-hours (kWh) generated. This is usually only applied to utility-scale systems.

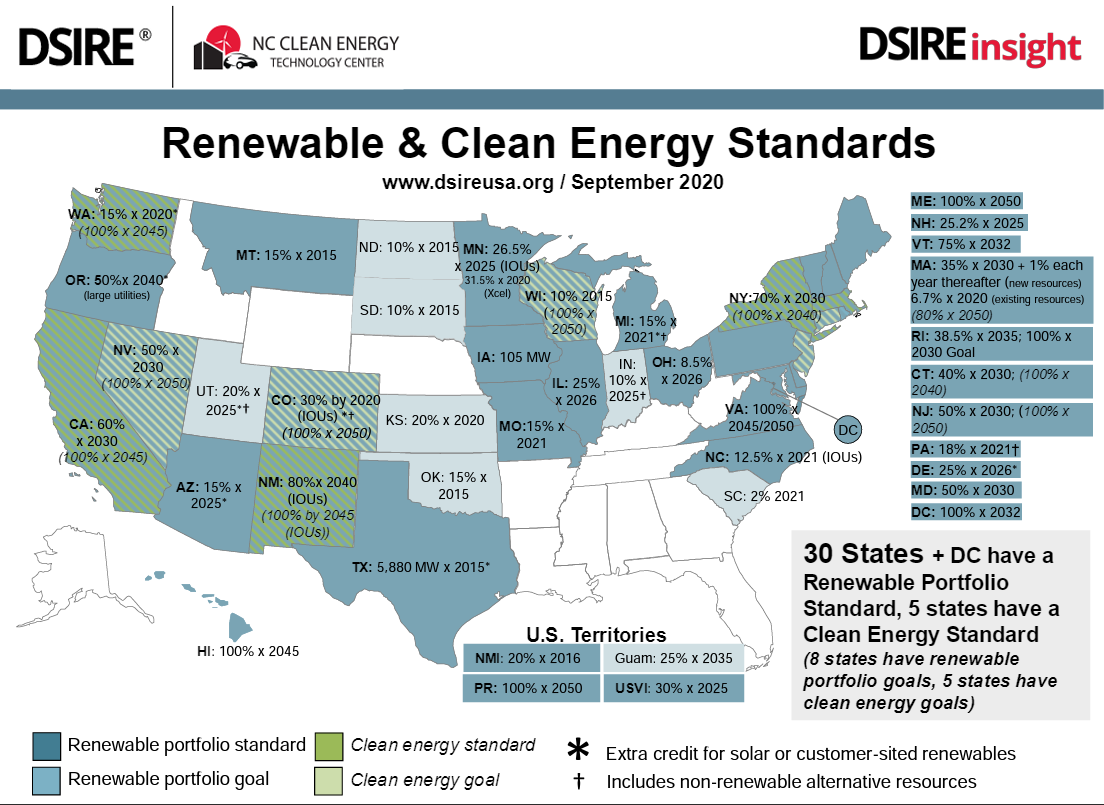

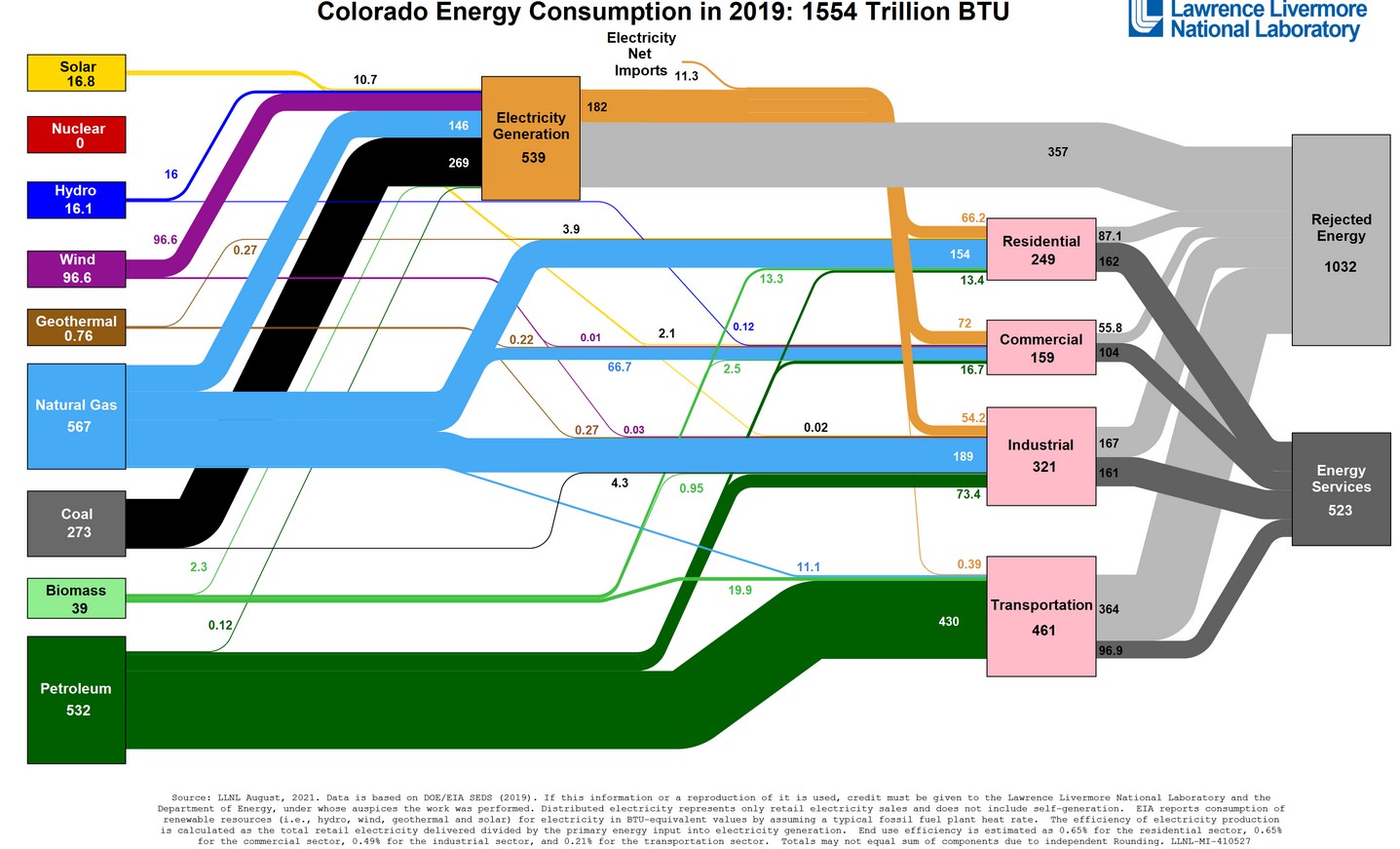

Rnewable portfolio standard (RPS) are very imnportant policies. Breifly, an RPS requires utilities to use renewable energy credits (RECs) to account for a certain percentage of their retail electricity sales. (RPSs are established by state legislatures, and not all states have an RPS policy.) A REC is earned by a qualified grid-tied facility for every 1,000 kWh (i.e., 1 MWh) of electricity that is generated using a renewable energy resource. The RECs are then bought and sold through a market. The settlement price varies depending on REC supply and demand at any point in time, though special auctions with guaranteed pricing and incentives are sometimes used. If you live in a state that has an RPS policy, you can "sell" your credits on an annual basis and receive a payment. For example, if you generate 7,000 kWh in a years and you can sell your credits for $40/MWh, you would earn $280 (7,000 kWh = 7 MWh x $40/MWh). You would receiv a check for this at the end of the year. See below for states that have RPS policies.

Another type of production-based incentive, a feed-in-tariff (FIT) pays grid-tied renewable energy generators a specified price for the electricity they generate and guarantees them this price for a specified amount of time. This type of policy is widely used in Europe, most notably in Germany, but less so in the USA. This is also usually used on utility-scale systems.

Anaerobic Digestion

You may recall from EM SC 240N that bioenergy is energy that comes from living or recently living things. Common examples include wood from trees used for heating and ethanol from corn used as a gasoline additive. Another form - and one that we will see while traveling - is called anaerobic digestion. "Anaerobic" refers to "without air" and the "digestion" part refers to the microorganisms that digest organic material. Putting it together, anaerobic digestion refers to microorganisms breaking down organic material when no oxygen is present. The following descriptions of anaerobic digestion are from the EPA's Anaerobic Digestion website. All points of emphasis (bold letters) are mine:

Anaerobic Digestion

Anaerobic digestion is the natural process in which microorganisms break down organic materials. In this instance, “organic” means coming from or made of plants or animals. Anaerobic digestion happens in closed spaces where there is no air (or oxygen). The initials “AD” may refer to the process of anaerobic digestion or the built system where anaerobic digestion takes place, also known as a digester.

The following materials are generally considered “organic.” These materials can be processed in a digester:

- Animal manures;

- Food scraps;

- Fats, oils, and greases;

- Industrial organic residuals; and

- Sewage sludge (biosolids).

All anaerobic digestion systems adhere to the same basic principles whether the feedstock is food waste, animal manures or wastewater sludge. The systems may have some differences in design but the process is basically the same

Byproducts of Anaerobic Digestion

Biogas is generated during anaerobic digestion when microorganisms break down (eat) organic materials in the absence of air (or oxygen). Biogas is mostly methane (CH4) and carbon dioxide (CO2), with very small amounts of water vapor and other gases. The carbon dioxide and other gases can be removed, leaving only the methane. Methane is the primary component of natural gas.

The material that is left after anaerobic digestion happens is called “digestate.” Digestate is a wet mixture that is usually separated into a solid and a liquid. Digestate is rich in nutrients and can be used as fertilizer for crops

Uses of Anaerobic Digestion Byproducts

Biogas is produced throughout the anaerobic digestion process. Biogas is a renewable energy source that can be used in a variety of ways. Communities and businesses across the country use biogas to:

- Power engines, produce mechanical power, heat and/or electricity (including combined heat and power systems);

- Fuel boilers and furnaces, heating digesters and other spaces;

- Run alternative-fuel vehicles; and

- Supply homes and business through the natural gas pipeline

How biogas is used and how efficiently it’s used depends on its quality. Biogas is often cleaned to remove carbon dioxide, water vapor and other trace contaminants. Removing these compounds from biogas increases the energy value of the biogas...Biogas treated to meet pipeline quality standards can be distributed through the natural gas pipeline and used in homes and businesses. Biogas can also be cleaned and upgraded to produce compressed natural gas (CNG) or liquefied natural gas (LNG). CNG and LNG can be used to fuel cars and trucks.

Digestate is the material that is left over following the anaerobic digestion process. Digestate can be made into products like:

- Bedding for livestock;

- Flower pots;

- Soil amendments; and

- Fertilizers.

When properly processed, dewatered digestate can be used as livestock bedding or to produce products like flower pots.

Digestate can be directly land applied and incorporated into soils to improve soil characteristics and facilitate plant growth. Digestate can also be further processed into products that are bagged and sold in stores. Some emerging technologies can be employed post-digestion to recover the nitrogen and phosphorus in digestate and create concentrated nutrient products, such as struvite (magnesium-ammonium-phosphate) and ammonium sulfate fertilizers.

The video below from Michigan State University does a great job of explaining how they use anaerobic digestion to convert organic cafeteria and farm waste into useful energy and fertilizer. To view the transcript (and the video on YouTube, click this link [19].)

The South Campus anaerobic digester at Michigan State University aims to reduce odor and emissions from manure, food waste and biosolids, create a closed cycle for recycling organic material, and generate renewable energy. The digester will use a mix of dairy manure, dining hall food waste, biosolids (which are nutrient-rich organic materials), and other organic material from campus in the greater Lansing area. Once delivered, the food waste and biosolids will be treated (heated and pasteurized) at 160 degrees Fahrenheit for one hour to eliminate any potential pathogens. The material will then be mixed with manure from the MSU Dairy Teaching and Research Center and pumped into the digester.

The anaerobic digester is a sealed, airtight tank, which can hold 300,000 gallons. Organic material will be heated to 100 degrees Fahrenheit and will remain in the digester for 20 to 30 days. Inside the tank, mixers in the digester evenly distribute microorganisms. These microorganisms break down the mixture, producing biogas and nutrient-rich digestate. Biogas, which is roughly 60% methane, is a form of renewable energy which will be used to generate electricity. The system will generate enough electricity to offset the MSU DTRC, around 300 kilowatts per hour, with enough left over to help power MSU. The capturing and use of biogas will generate energy, shrink the carbon footprint of campus, and improve sustainability. What's left in the process is digestate, the nutrient-rich mixture that will be held in the final, storage tank until it can be utilized. Mixers in the storage tank will minimize settling for the potential 2.7 million gallons of digestate. Any unused biogas can also be stored in the sealed headspace. The nutrient-rich digestate will be used to fertilize croplands or other biological treatment processes to fuel research opportunities.

By utilizing anaerobic digestion technology, the organic materials from MSU will become resources. Renewable energy is created, while odors are reduced and emissions are eliminated. This project is one example of how Michigan State University is actively working to improve sustainability.

Thermodynamically speaking, the energy conversion process is:

- Sunlight is converted to biomass by plants.

- Plants are either used in the digester and converted to methane and CO2 or...

- Biomass is eaten by animals and converted to another form of biomass.

- Organic waste from animals is used in the digester and converted to methane and CO2.

- The methane can then be used for electricity and/or heat.

It is extremely important to keep in mind that this is a natural process, and thus will occur any time organic material is subjected to low- or no-oxygen conditions. One important implication of this is that organic material that ends up buried in a landfill will convert partially to methane because there is very little oxygen underneath all of that "junk." As I'm sure you recall, methane is about 30 times more potent than CO2 in terms of its global warming impact. If you took the same organic material and let it biodegrade in the open air (i.e., with access to oxygen) it would release mostly CO2. The sad irony of this is that well-meaning people and companies can actually make the (climate change) problem worse if their biodegradable containers end up in the landfill. This methane can be captured, and in many places in the U.S. and throughout the world is. This is also why impoundment hydroelectric facilities (big dams) can cause methane emissions - organic material collects upstream of the dam, and low-oxygen conditions often occur near the bottom of the reservoirs, causing methane to be released. Systems thinking, everyone!

Anaerobic Digestion Examples

Digesters can be pretty much any size. I've seen one as small as a car inner tube that was used to power a gas grill and heat a small greenhouse. Some of them can be larger, as you'll see below.

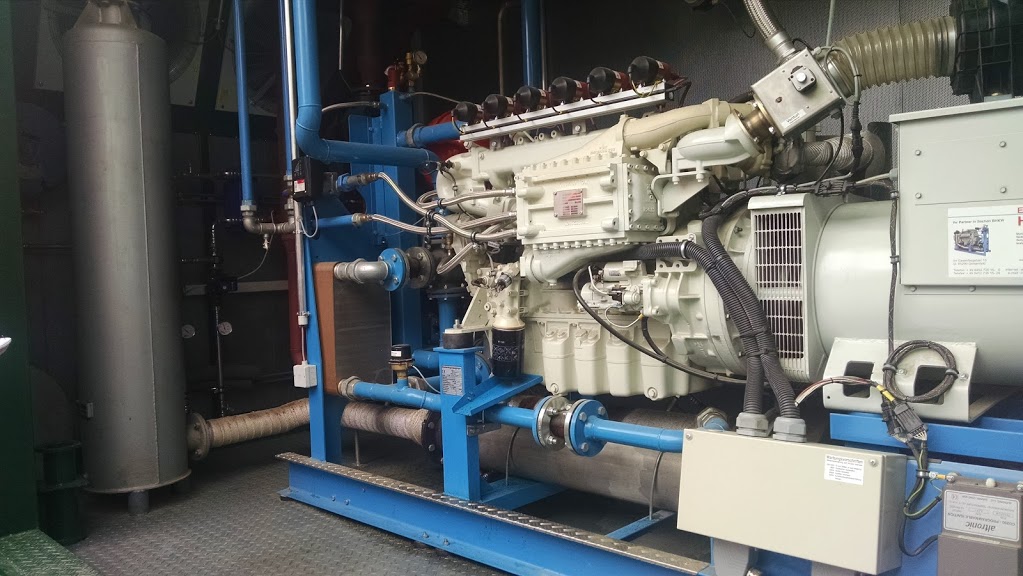

The pictures below are from a cooperatively-owned anaerobic digester in Lemvig, Denmark. I'm particularly fond of this because the entire setup is owned equally by about 25 farmers, and is a non-profit operation. All of the organic waste from the farms is transported to the digester, including leftover vegetation and various types of manure. The biogas is used to generate electricity in a turbine which is either sold to the grid or used in the digester, and the "waste" heat is used to run the anaerobic digester. The remaining heat is used for district heating for the town - it heats up water, which is then run through underground pipes to be used to heat homes. This type of generator is considered cogeneration, which means it is used to generate electricity and useful heat. Recall that most power plants are about 35% efficient because so much energy is wasted as heat. Believe it or not, this cogeneration system is over 90% efficient when you include all of the "waste" heat that is captured and used! All digestate is then returned to the local farms and used as organic fertilizers. It is truly a closed-loop system!

The images below show details of a smaller installation in Kussnacht, Switzerland. This installation is run by a single farmer (Seppi), who collects organic waste from his farm, other local farms, and area restaurants. Like the one above, Seppi collects the biogas and uses it in a cogeneration system that is about 90% efficient (50% heat, 40% electricity, and 10% is wasted). He runs a 100 kW generator and uses the electricity on his farm and sells the leftover to the grid. The heat is used to run the digester, and to provide space and water heating to his farm. He uses some digestate on his farm and gives the rest back to local farmers for free.

It just so happened that at the time of our visit (I brought students there for a study abroad experience), his previous digester had burnt down due to a generator fire. The upshot of this is that we were able to see inside the digester he was building, which you will see below.

Summary and Final Tasks

Summary

By now you should be able to:

- identify different types of solar technologies;

- explain the basic process by which solar panels generate electricity;

- explain the difference between irradiance and irradiation;

- calculate energy use/generation given power and time;

- evaluate the impact of tilt and orientation on solar PV output;

- calculate the output of a solar array;

- explain how anaerobic digestion converts organic material to biogas; and

- identify some of the benefits of anaerobic digestion.

Reminder - Complete all of the Lesson 1 tasks!

You have reached the end of the lesson! Double-check the to-do list on the Lesson Overview page [20] to make sure you have completed all of the activities listed there before you begin the next lesson..

Lesson 2: Wind and Microhydro

Overview

In this lesson, we'll go over some of the basics of wind and microhydroelectric energy, including how to do some basic output calculations.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- analyze wind energy maps;

- identify components of wind turbines;

- describe how solar energy is converted to wind and hydropower;

- calculate the output of a wind turbine;

- identify components of microhydro systems; and

- calculate the output of a microhydro system.

Lesson Roadmap

| To Read | Lesson 2 Online Content | You're here! |

|---|---|---|

| To Do |

|

|

Questions?

If you have any general course questions, please post them to our HAVE A QUESTION discussion forum located under the Discussions tab in Canvas. I will check that discussion forum regularly to respond as appropriate. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses and comments if you are able to help out a classmate. If you have a question but would like to remain anonymous to the other students, email me through Canvas.

If you have something related to the material that you'd like to share, feel free to post to the Coffee Shop forum, also under the Discussions tab in Canvas.

Wind Energy

As you may recall, the wind is caused by differential solar heating across the surface of the earth (as well as the shape of the earth), which causes large- and small-scale high and low-pressure systems to form. Air moves from areas of higher pressure to areas of lower pressure, which is what causes wind to occur. (If you are interested, this National Geographic site [21] explains some of the finer points of this process, including a lot of pictures.)

Wind, then, is just air that is moving. Simply put, this air has kinetic energy because wind has mass and is moving. (Anything in motion with mass has kinetic energy.) Because of the First Law of Thermodynamics, the energy in the wind must come from somewhere else. This "somewhere else," is solar energy. This energy (and power) can be quantified. See later in this lesson for an explanation of how to calculate this.

Wind Resources in the U.S.

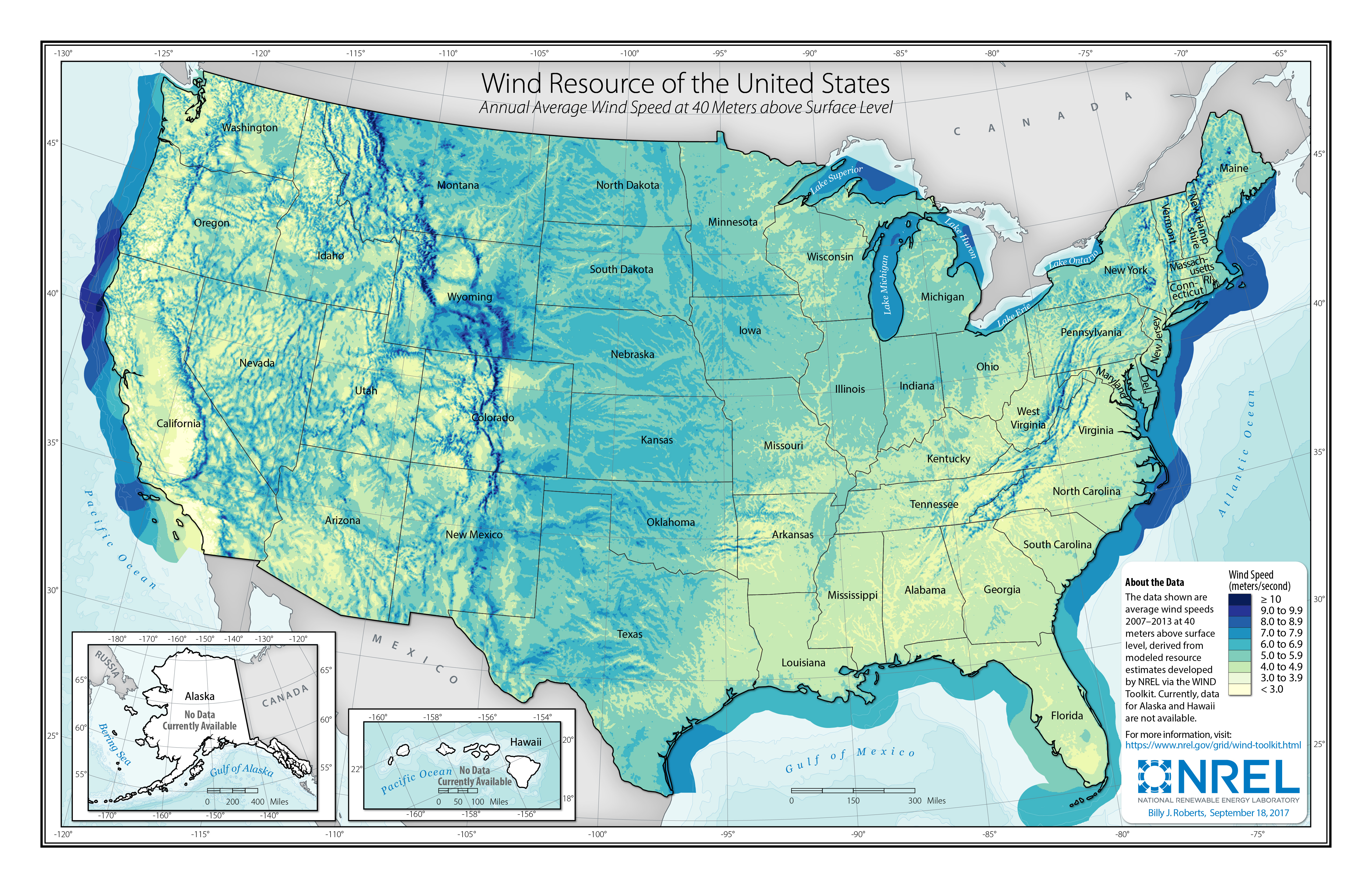

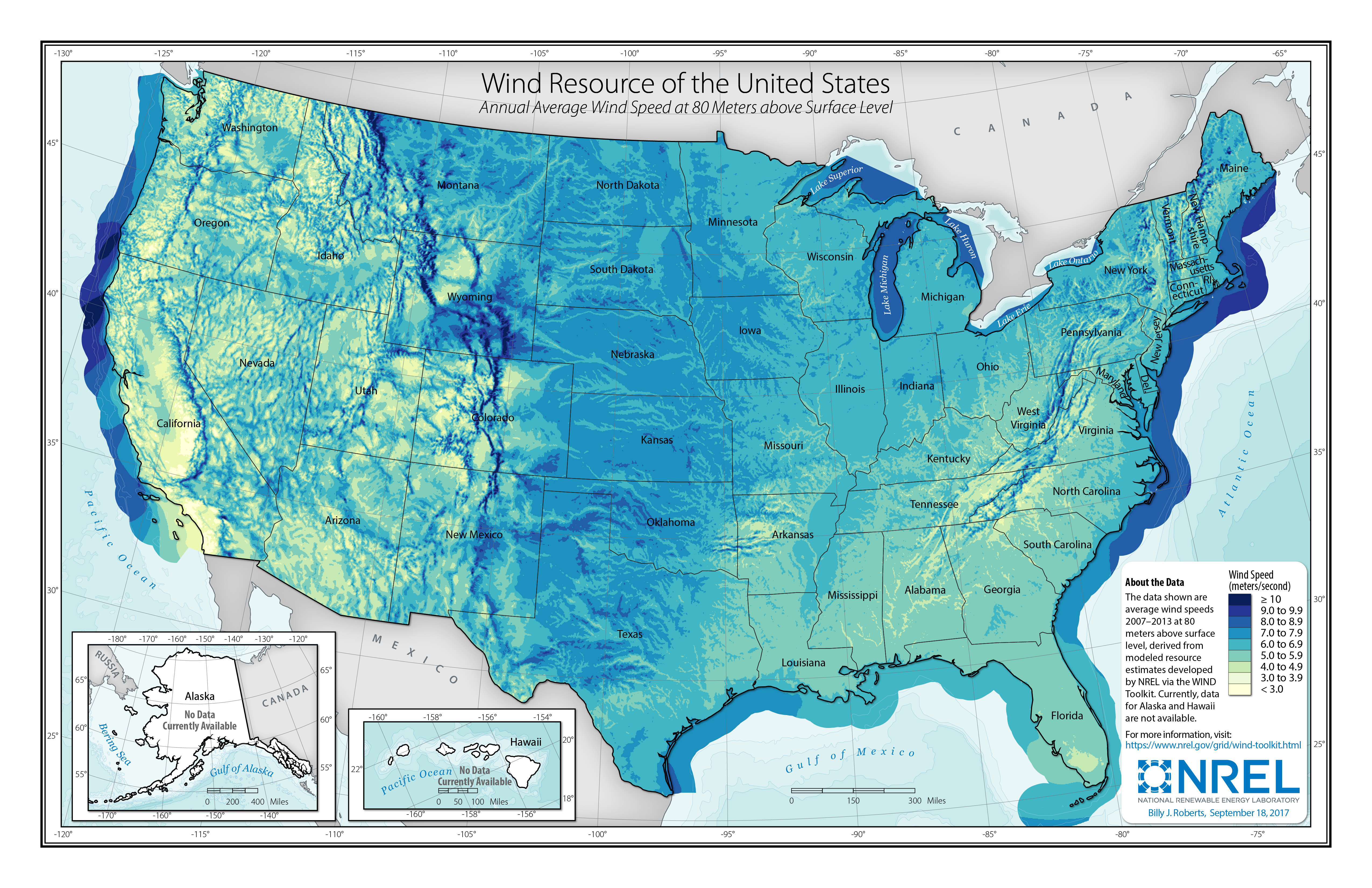

Average wind speeds vary widely by geographical location. Take a few minutes to inspect the wind speed charts from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory below. Note the location of the greatest and smallest wind speeds, and think about the physical characteristics of those areas (e.g., flat, mountainous, on-shore, off-shore, etc.). Click here for a larger version of the 40 m wind speed image [22] and click here for the 80 m image. [23] Note that the average wind speed is higher at 80 m at the same location. Wind speed generally increases with height due to the decreasing influence of friction from the earth's surface and things on it. Modern turbines are generally tall enough to take advantage of 80 m wind speeds.

In addition to variability being a barrier to wind deployment, the location of wind resources is as well. In general - and certainly, in the U.S. - the best onshore wind resources are not located near major population centers. Approximately 50% [24] of the U.S. population lives within 50 miles of the coast, but as you can see in the maps below, this is generally not where the greatest onshore wind is located. This is a problem because transporting electricity over power lines results in energy loss (as heat) due to electrical resistance in wires. The longer the electricity has to travel, the more energy is lost. To minimize this loss, large (and very expensive) power lines must be built. As you can imagine, this type of infrastructure is lacking in areas of the country that do not have large populations.

However, it is clear from the second map that significant offshore wind resources are available very near the coast. Unfortunately, offshore wind is still expensive (remember from a previous lesson [25] that the LCOE is the highest of those listed). That, combined with resistance from local inhabitants had kept the offshore wind at bay until 2016 when the first offshore wind farm (albeit a very small one) in the U.S. was opened in Rhode Island [26]. There are over two dozen in the planning stages [27] as we speak. This is likely an area of growth in the near future.

Wind Turbines

To Read and View Now

- Read through the "Types of Wind Turbines" section of How a Wind Turbine Works [29], and click through the animation from U.S. DOE.

Now for some terminology and other considerations:

- Wind turbines convert wind to electricity. This is different than a windmill, which converts wind energy into mechanical energy that is used for another purpose (e.g., pumping water or in the "old days," grinding grain).

- A wind farm is a number of turbines that are installed in the same area, usually by the same company.

- Like solar panels, turbines have a capacity, which refers to the maximum electrical output of the turbine. A 2 MW turbine will output 2 MW of power at its peak. The amount of power is dictated by the velocity of the wind.

- Remember that energy = power x time, so if a turbine is operating at 2 MW for 1 hr, it will output (2 MW x 1 hr = ) 2 MWh of electricity. 2 MW is now considered a moderately large utility-scale turbine.

- A residential-scale turbine is much smaller, usually being a few hundred watts to a few kilowatts in size. For an example, see the image of the 2.4 kW residential turbine below. If this turbine is generating 2.4 kW for 10 hr, it would generate (2.4 kW x 10 hr = ) 24 kWh of electricity.

- Similar to solar, energy generation by a turbine is maximized by pointing the turbine so it is perpendicular to the wind. Large turbines have a mechanism that rotates the turbine so it faces the wind. This movement is called yaw.

See below for a diagram of key components of wind turbines:

There is a lot to digest here. The components I'd like you to know are as follows. All quoted text is from the U.S. Department of Energy [30]:

- Blades: "Lifts and rotates when wind is blown over them, causing the rotor to spin." The blades convert wind energy into motion energy (the rotating rotor).

- The hub (which is not indicated in the image) is the "nub" in front of the blades. Turbine heights are usually expressed using "hub height," which indicates how far above the ground the center of the hub is.

- The "blades and hub together form the rotor."

- The rotor spins the low-speed shaft, which is then (usually) converted to a higher rotation speed through a gear box.

- The high-speed shaft is attached to the other side of the gear box, which spins the generator. The generator converts this motion energy into electrical energy. Unlike solar panels, wind turbines generate AC electricity.

- The nacelle "sits atop the tower and contains the gear box, low- and high-speed shafts, generator, controller, and brake. Some nacelles are large enough for a helicopter to land on."

- The tower "supports the structure of the turbine." Modern turbines use cylindrical towers made of steel.

- Not pictured, but some modern turbines skip the gear box and use direct drive technology, spinning the generator at the same rpm as the low-speed shaft.

The basic energy conversion process is as follows:

- Solar energy is converted to wind energy.

- Wind energy is converted to motion energy by the blades, which rotates the shaft.

- The rotational velocity of the shaft is increased through the gear box. This does not increase the energy, and in fact, loses some due to frictional heat loss in the gear box.

- The gear box spins another shaft, which spins the generator.

- The generator generates an electrical current.

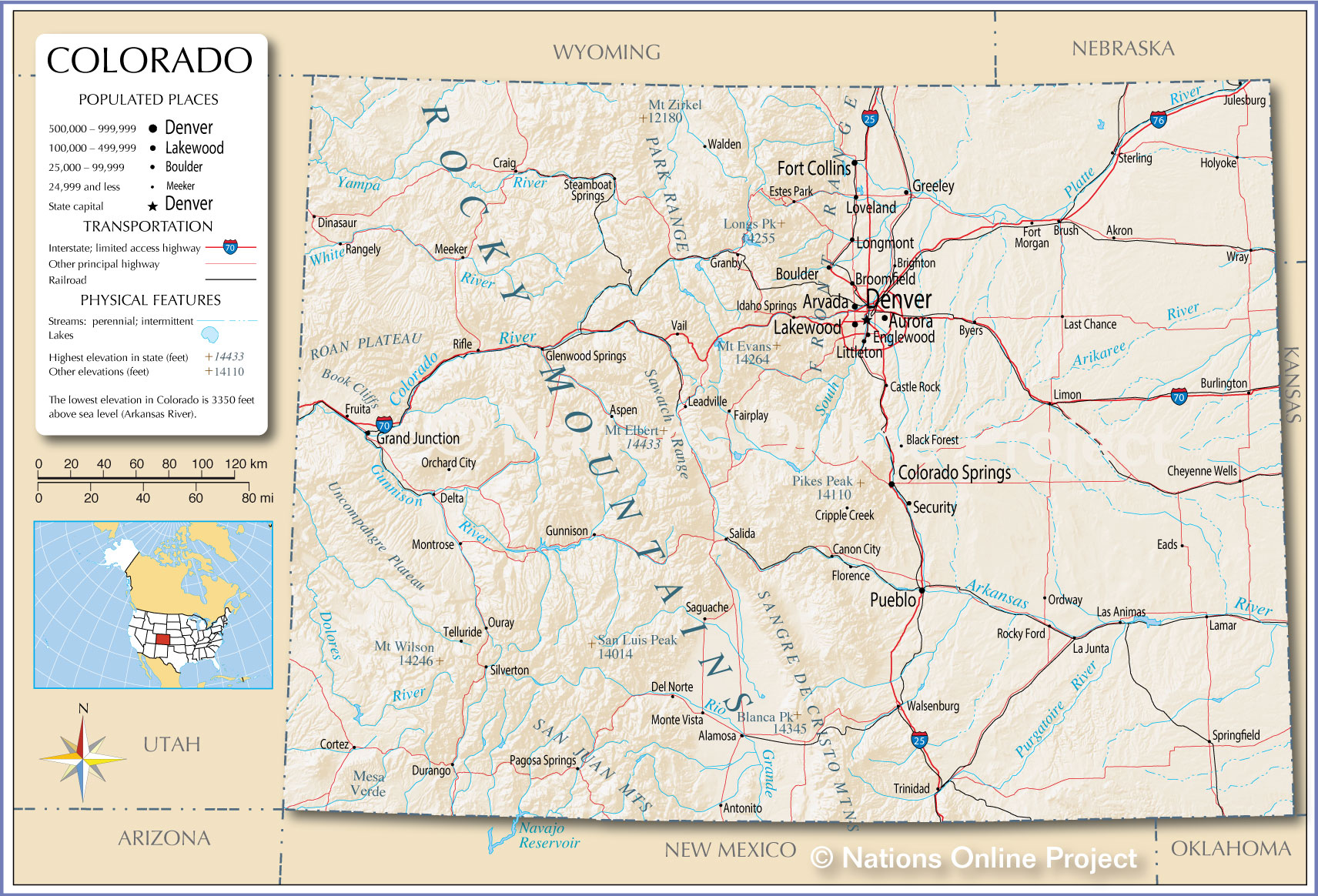

Turbines come in a very wide variety of sizes and capacities. The images below show some of this. (We will see the second turbine in Golden, CO!)

Wind Energy and Power Calculations

The power in the wind is given by the following equation:

Power (W) = 1/2 x ρ x A x v3

- Power = Watts

- ρ (rho, a Greek letter) = density of the air in kg/m3

- A = cross-sectional area of the wind in m2

- v = velocity of the wind in m/s

Thus, the power available to a wind turbine is based on the density of the air (usually about 1.2 kg/m3), the swept area of the turbine blades (picture a big circle being made by the spinning blades), and the velocity of the wind. Of these, clearly, the most variable input is wind speed. However, wind speed is also the most impactful variable because it is cubed, whereas the other inputs are not.

The following are calculations for power available in the wind at three different velocities for the Northwind 100C turbine. This is the newer version of the Northwind 100A on the previous page. The calculations will show what happens when you double, then triple the velocity. Take a moment to think about how much available power will increase if you double and triple the velocity:

- The standard [34] density of air is 1.225 kg/m3

- The turbine has a 24 m diameter, which means the radius is 12 m. Thus, the swept area of the turbine is: (pi)r2 = 3.14159(122) = 452.4 m2

- We'll start with a 6 m/s wind.

- The power in the wind at 6 m/s is: 1/2 x ρ x A x v3 = 0.5 x 1.225 kg/m3 x 452.4 m2 x (6 m/s)3 = 59,851 W = 59.85 kW

- At 12 m/s: 1/2 x ρ x A x v3 = 0.5 x 1.225 kg/m3 x 452.4 m2 x (12 m/s)3 = 478,808 W = 478.8 kW (8 times as large)

- At 18 m/s: 1/2 x ρ x A x v3 = 0.5 x 1.225 kg/m3 x 452.4 m2 x (18 m/s)3 = 1,615,979 W = 1,616 kW = 1.616 MW (27 times as large)

As you can see, when the velocity doubles, the power increased by a factor of 8 and when the velocity triples, it increases by a factor of 27. This is because the velocity is cubed: 23 = 8 and 33 = 27.

Calculating Wind Turbine Output

The output of a wind turbine is dependent upon the velocity of the wind that is hitting it. But as you will see, the power is not proportional to the wind velocity. Every turbine is different. In order to determine the output of a specific turbine at a given wind velocity, you need its power curve. The power curve and corresponding data for the Northwind 100C can be seen below:

| wind speed (m/s) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| power output (kW) | -0.5 | -0.5 | 1.2 | 7.2 | 14.5 | 24.7 | 37.9 | 58.7 | 74.8 | 85.1 | 90.2 | 94.7 |

| wind speed (m/s) | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| power output (kW) | 95.3 | 95.1 | 94.2 | 92.9 | 91.2 | 88.9 | 87.1 | 84.1 | 81.3 | 78.6 | 75.1 | 74.3 | 71.7 |

As you can see, even though this is a 95 kW turbine, it only provides (approximately) that much power at a very limited number of wind speeds - about 12 m/s through about 15 m/s. Counterintuitively, the power output decreases if the wind speeds up past that point. For safety reasons, the turbine will stop spinning if the wind speed is higher than 25 m/s.

Assuming the turbine is operating properly, the output calculation is pretty straightforward. You just multiply the output at a given velocity by the number of hours the wind is blowing at that velocity. For example, let's assume that the wind hitting a Northwind 100C in a given day has the following velocities. (Note that in reality, the wind would likely change much more frequently than this. I just wanted to make the math relatively easy.):

| velocity (m/s) | number of hours at that velocity |

|---|---|

| 6 | 4 |

| 8 | 8 |

| 12 | 5 |

| 15 | 4 |

| 16 | 3 |

| 16 | 3 |

The total output at 6 m/s would be: 24.7 kW (the output at 6 m/s from the power curve table) x 4 hrs = 98.8 kWh.

Based on the power curve table above, the total output for this day would be:

| velocity (m/s) | number of hours at that velocity | total output (kWh) |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 4 | 98.8 |

| 8 | 8 | 469.6 |

| 12 | 5 | 473.5 |

| 15 | 4 | 376.8 |

| 16 | 3 | 278.7 |

| 16 | 3 | 278.7 |

| Total | 24 | 1,697.4 |

Capacity Factor

One last consideration to make for wind turbines (or any energy source) is something called capacity factor. Capacity factor indicates how much energy is generated by a source relative to the maximum amount of energy it could provide. This is expressed as a percentage, and is usually determined over the course of a single year. This provides insight into how well-sited the turbine is, but in general indicates how available an energy source is throughout the year. The closer to 100%, the more the energy source is available throughout the year.

The formula is capacity factor = actual output/maximum possible output.

For a wind turbine, the maximum possible output would be the capacity x 8760 hr (there are 8760 hrs in a year). So for the Northwind 100C, the maximum output is: 95 kW x 8760 hr/yr = 832,200 kWh/yr (or 832.2 MWh). If the actual output over the course of a year was 250,000 kWh, the capacity factor would be:

- capacity factor = actual/maximum output = 250,000 kWh/832,200 kWh = 30%

The average capacity factor of the U.S. wind fleet hovers around 32% - 34% [36], but new turbine designs have been tested in the 60%+ range, like the 12 MW behemoth [37] by GE. It's not unusual to see 40% and up capacity factors for well-sited wind farms.

Microhydro

Hydropower

Like moving air, moving water has kinetic energy (it has mass and it is moving). But water is much denser than air - this is obvious to anyone who has waded across a deep stream or played in ocean waves. If you recall, air has an average density of 1.225 kg/m3. One cubic meter of water, on the other hand, has a mass of 1,000 kg, or one metric ton (aka one tonne). It may be hard to believe, but a cube of water that is about 3.3 feet on each side weighs over 2,000 pounds!

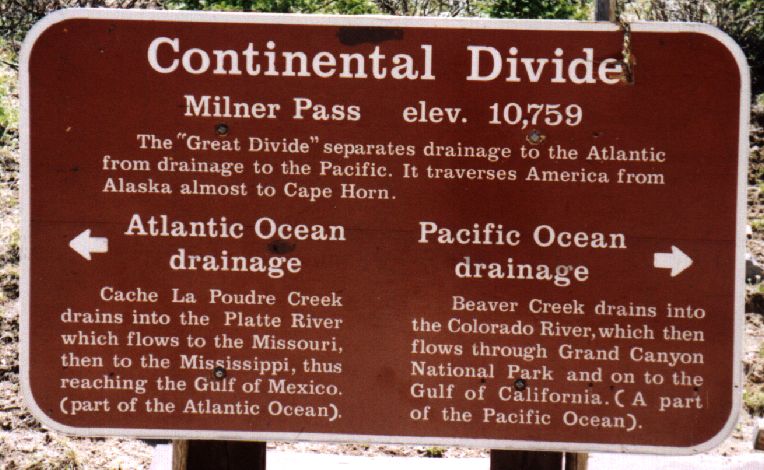

Where does this kinetic energy come from? Take a second to think about it...Water only flows downhill, so if you see moving water it came from a higher elevation. This kinetic energy is thus converted from gravitational potential energy. How did it get this gravitational potential energy? Well, something had to take the water up to the higher elevation. The only natural way this happens is through evaporation, which is almost always caused by the sun, in a number of different ways: Water that is heated by the sun may evaporate. Wind also evaporates water, but remember that wind gets its energy from the sun. Plants evapotranspirate water, but again, they get their energy from the sun. Even the minor amount exhaled by humans is solar energy since all of our energy comes from the sun. The only major exception is that some evaporative heat is provided by geothermal energy from the earth, e.g., in volcanoes. At any rate, almost all hydropower/energy comes from the sun

How a Hydropower Plant Works

Humans have been using hydropower for thousands of years [38]. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, the Greeks used water to spin wheels to grind grain over 2,000 years ago. Modern humans figured out how to convert hydropower to electricity by using a turbine and generator (see below), which is called hydroelectricity, for obvious reasons. The first known use of hydroelectricity [39] was in 1878 to power a single lamp in Northumberland, England. Larger plants were installed in 1881 in the U.S., and the first commercial-scale plant was built in the U.S. in 1893 in Redlands, California.

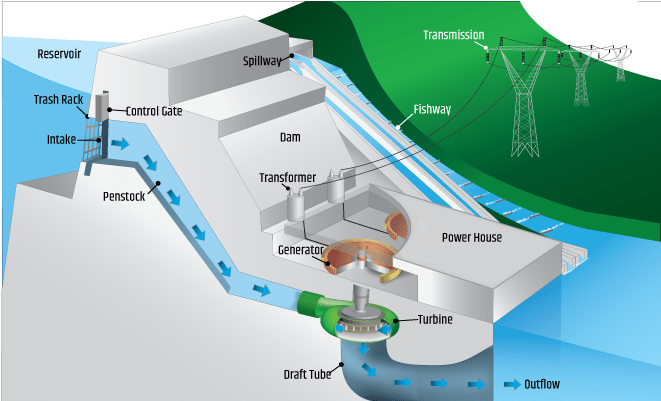

All hydroelectric power plants operate on the same principle. Moving water spins a turbine, which spins an electric generator. See below for an illustration of an impoundment facility, which uses a dam to create a reservoir of water.

[40]

[40]

Explaining all components in this image goes beyond the scope of this lesson. The important terms for this lesson are:

- The penstock is a conduit through which the water flows from a higher to a lower elevation.

- The turbine spins due to the force of the water flowing out of the penstock.

- The turbine spins the generator, which generates electricity.

This basic process - flowing water spins a turbine, which spins a generator - is common to all types of hydroelectricity installations. There can be any number of other components, and the size/scale may be different, but this core process is the same.

Microhydroelectricity

Like all other electricity sources, hydroelectric power plants have a rated capacity. Large impoundment facilities can have capacities on the order of GWs (billions of watts). The largest facility in the world - the Three Gorges Dam in China - has a capacity of 18 GW. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, a microhydro system has a capacity of up to 100 kW [41]. Most systems are much smaller. A residential-scale microhydro system is more likely to be a few kWs in size.

A typical microhydro system is illustrated in the image above. Systems can vary significantly in style and size, but according to the U.S. DOE, the following components are commonly seen in most systems [44]:

- The water is often diverted from a stream. If so, it is usually transported to a forebay, which is akin to a small impoundment facility that creates a small reservoir.

- There is some kind of conveyance that provides the water to the turbine. In the illustration above, this is done by a penstock, which is often made of PVC pipe. This could also be done by a channel.

- The water spins a turbine, which spins a generator, which provides electricity. This is all contained in the powerhouse in the image above. There are a number of different types of turbines, most of which require a jet of water that is sprayed through a nozzle at the end of the penstock. If you are interested, see details in this reading from the U.S. DOE [44].

Energy and Power in Water

As described above, the kinetic energy in flowing water starts out as gravitational potential energy. The gravitational potential energy of a given amount of water at any elevation can be calculated using the following equation:

- Pe = m x g x h

- Pe = potential energy in Joules

- m = the mass of the water in kg

- g = the acceleration due to gravity (m/s2)

- h = the height of the water in m (usually called the "head")

The force of gravity is essentially a constant (it gets a little bit smaller with height). Thus, all else being equal, as height and mass increase, the potential energy increases. Keep in mind that this equation only illustrates the maximum kinetic energy available to a hydropower system. In reality, there are always losses by the time the kinetic energy is converted to electricity.

The power available in water at height is given by a similar equation:

- P = Q x g x h

- P = power in watts

- Q = discharge of water in kg/s (this is also mass per unit time)

- g = acceleration due to gravity (m/s2)

- h = head (m)

Again, this is only the hypothetical maximum - it is impossible to capture all of this power in a turbine. This equation is almost the same as the potential energy equation - you just substitute discharge for mass. Since the discharge is kg/s, or mass divided by time, if you compare the two equations, the power equation is the energy equation divided by seconds. This makes sense if you think about it: the potential energy is given in Joules, and the power equation is given in watts. Recall that 1 J/s = 1 W. Makes sense, right?

Calculating Microhydro Output

It turns out that calculating the approximate power output of a microhydro system is not terribly difficult. According to the U.S. DOE, a typical system has an efficiency of about 53%. This includes losses from the nozzle, the wiring, the generator, and a few other things. The power of a microhydro system with this efficiency is approximately:

- power = net head x flow /10

- power = electric power in W

- net head = the gross head in ft including the head loss in the penstock

- flow = flow of water in gal/min

- 10 = conversion factor (this can range from 8 - 12, with 10 being about average)

To determine the gross head, you measure how many feet above the generator the penstock starts. Note that this is not the same as the length of the penstock. The penstock is sloped, and thus will be longer than the head. The head loss is based on a few factors, including the diameter of the penstock, the pressure inside the penstock, and the number of turns and fittings there are in the penstock. According to Homepower Magazine, 30% is a typical amount of head loss, which means you would calculate the gross head time 0.7 to determine the net head. The flow of a stream through a penstock can vary wildly, from a few gallons per minute to a few hundred (or more). To provide some context a garden hose usually has a flow of about 20 gallons per minute, though this can also vary significantly depending on a number of factors.

Let's say I have a property in which I can create a diversion channel and forebay 100 ft above a power house, and I measure my flow at 50 gpm. Assuming a good system design which includes a head loss of 30%, my output would be:

- power = net head x flow / 10

- power = 100 ft x 0.7 x 50 / 10 = 350 W

- If I could get this to operate all day, I would get (350 W x 24 h/day = ) 8400 Wh or 8.4 kWh/day

Further Reading/Viewing

This lesson only scratches the surface of microhydro systems. There are many designs and factors to consider. Each site is different. For a more detailed explanation, see this website from the U.S. DOE [45], and for a good case study, see this example from Homepower Magazine ( [46]starting on p. 32). There are dozens of videos on YouTube that detail specific systems, many of which are worth checking out if you are interested.

If you are interested in learning more about the power and energy available in water for hydroelectric, see this video presentation I put together [47]for another course.

Site Visits

Starting this week and moving forward — each week, I will provide links to some of the locations/organizations we will visit. This is not required reading. I suggest browsing through them if/when you have time. This may help inspire your final project proposals!

- Solar Energy International [48] (SEI), Paonia

- GRID Alternatives [49], Denver

- Rocky Mountain Institute [50], Boulder

- Blue Terra Waste Solutions [51], Denver and Longmont

Summary and Final Tasks

Summary

By now, you should be able to do the following:

- analyze wind energy maps;

- identify components of wind turbines;

- describe how solar energy is converted to wind and hydropower;

- calculate the output of a wind turbine;

- identify components of microhydro systems; and

- calculate the output of a microhydro system

Reminder - Complete all of the Lesson 7 tasks!

You have reached the end of Lesson 7! Double-check the to-do list on the Lesson 7 Overview page [52] to make sure you have completed all of the activities listed there before you begin Lesson 8.

Lesson 3: Waste Management

Overview

The focus of this lesson is on ways to sustainably manage natural resources.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- define natural resources;

- describe why the term "natural resources" is anthropocentric;

- analyze the difference between linear and circular resource flows;

- describe the differences between reduction, reuse, and recycling; and

- identify components of the circular economy and cradle to cradle certification.

Lesson Roadmap

| To Read | Lesson 8 Online Content | You're here! |

|---|---|---|

| To Do |

|

|

Questions?

If you have any general course questions, please post them to our HAVE A QUESTION discussion forum located under the Discussions tab in Canvas. I will check that discussion forum regularly to respond as appropriate. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses and comments if you are able to help out a classmate. If you have a question but would like to remain anonymous to the other students, email me through Canvas.

If you have something related to the material that you'd like to share, feel free to post to the Coffee Shop forum, also under the Discussions tab in Canvas.

Natural Resource Use

I'm sure you've heard the term "natural resources" used many times, e.g., when someone talks about "preserving natural resources" or when you hear about "natural resource management." It's a pretty innocuous term, and seemingly straightforward. If you asked someone what natural resources are, they would probably say something about "resources provided by nature, such as trees, minerals, and food" or something to that effect. (This is actually a pretty good definition, by the way!) When thinking about the definition, it's easy to focus on the "nature" component and look past the "resources" part. Specifically, it is important to note that "natural resources" is an anthropocentric (human-centered or focused) term. It is a concept that only exists because of humans because it refers to things that impact humans. To demonstrate this, let's look at a few definitions of natural resources:

things such as minerals, forests, coal, etc. that exist in a place and can be used by people

~Cambridge Dictionary [53]

industrial materials and capacities (such as mineral deposits and waterpoer) supplied by nature

~Merriam-Webster [54]

a naturally occurring source of wealth, as land or water; the natural wealth of a country, consisting of land, forests, mineral deposits, water, etc.

~dictionary.com [55]

Any way you slice it, without humans natural resources don't exist, they would just "be" or just be "nature." This is important to keep in mind as we go over this lesson: by definition, natural resources only exist as a concept because they can be used by humans.

Hidden Resource Use

Personal consumption expenditures (household spending on goods and services) constitutes nearly 70% of U.S. GDP [56]. Much of this is on services, but Americans now spend over 5.5 trillion dollars on "goods," which includes everything from food, to energy, to cars, houses, clothing, and other goods. See the charts below from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis [57] for these consumption trends over the past 60+ years. They are an excellent, reliable resource for economic data. (For a good explanation of goods and services, see this explanation [58]from thebalance.com.)

The moral of the story: Americans buy a lot of stuff! This has many implications, but one is particularly important with respect to this lesson. Namely, almost all of this spending requires the use of natural resources. Obviously, things like cars and clothes require raw natural resources to produce, though you may be surprised at how many. Take a look at the infographic below from Allianz to get some idea of how many different natural resources from all over the world are needed to make a car.

All goods require some mixture of raw natural resource extraction, manufacturing, processing, shipping, packaging, use, and disposal. All of this requires energy and resources. Most of this use, as indicated in the infographic above, is hidden.

I will give you one more quick example: I used to assist with industrial energy audits on a part-time basis while in college. One of the places we audited was a "feed mill," which is essentially a factory that produces chicken feed. (Related note: Delaware is considered the poultry capital of the U.S.) The facility looked a lot like the one in the image below.

I was dumbfounded at how much energy and resources went into just producing feed for chickens! While I was there, there was a constant arrival of tractor trailers hauling raw ingredients - corn, soybean, nutrient mixes, and other things - and the machinery was massive and energy-intensive. According to Delmarva Poultry Industry, Inc. [65] (Delmarva includes parts of Delaware and the eastern shores of Virginia and Maryland), the Delmarva chicken industry had the following specifics in 2020:

- 5.7 million chickens (4.2 billion pounds) produced

- They purchased "90 million bushels of corn, 36 million bushels of soybeans, 403.000 bushels of wheat," all for chicken feed. Imagine all of the water, fertilizer, and energy that went into the production of these crops.

- They "purchased $270 million in packaging and processing supplies."

The point here is not to go in-depth into the poultry or automobile industries, but to indicate that nearly everything you purchase is the product of a tremendous use of resources, much of which is hidden. But services such as healthcare and education also require the use of resources. Medical facilities need chairs, tables, x-ray machines, paper, and so forth, use a lot of energy, and create an immense amount of waste. Even an online class requires physical resources, in particular, electricity (e.g. cloud-based storage uses [66]about 70,000 - 140,000 times the energy of storing data on your computer), and all of the lifecycle resources used to generate that energy (mines, power plants, power lines, equipment to manage it all, etc.), but also the device you are viewing this on is the result of a global supply chain of goods, and there are natural resource impacts at every step of this supply chain. This type of lifecycle resource use and our consumption-driven economy are major contributors to the fact that we would need nearly 5 planet earths to satisfy humanity's needs if everyone lived like the average American.

Resource Flows

Linear Resource Flow

The problems associated with the massive amount of resources used to produce everyday goods and services is compounded by the fact that this system is based mostly on linear resource use. This is often referred to as "take, make, waste." An illustration of the basic resource flow is shown below.

This linear model typically goes something like the following:

- Natural resources are extracted through mining, growing, gathering, etc. They are often shipped all over the world, e.g., as indicated in the automobile infographic above.

- These raw resources are then manufactured into final goods, both perishable and non-perishable. This almost always occurs on an industrial scale (think of the massive factory farms, manufacturing plants, and even the feed mill illustrated above).

- These goods are then distributed, usually globally. Take a look at the label on your clothes (Bangladesh and Vietnam are common), electronics (China, most often), and food (could be anywhere - Chile, Mexico, New Zealand, etc.).

- They are then used by the end user.

- Most of the time, they are then disposed of in a landfill.

- Note that all along the way there are waste and emissions being generated, most of which are emitted or landfilled.

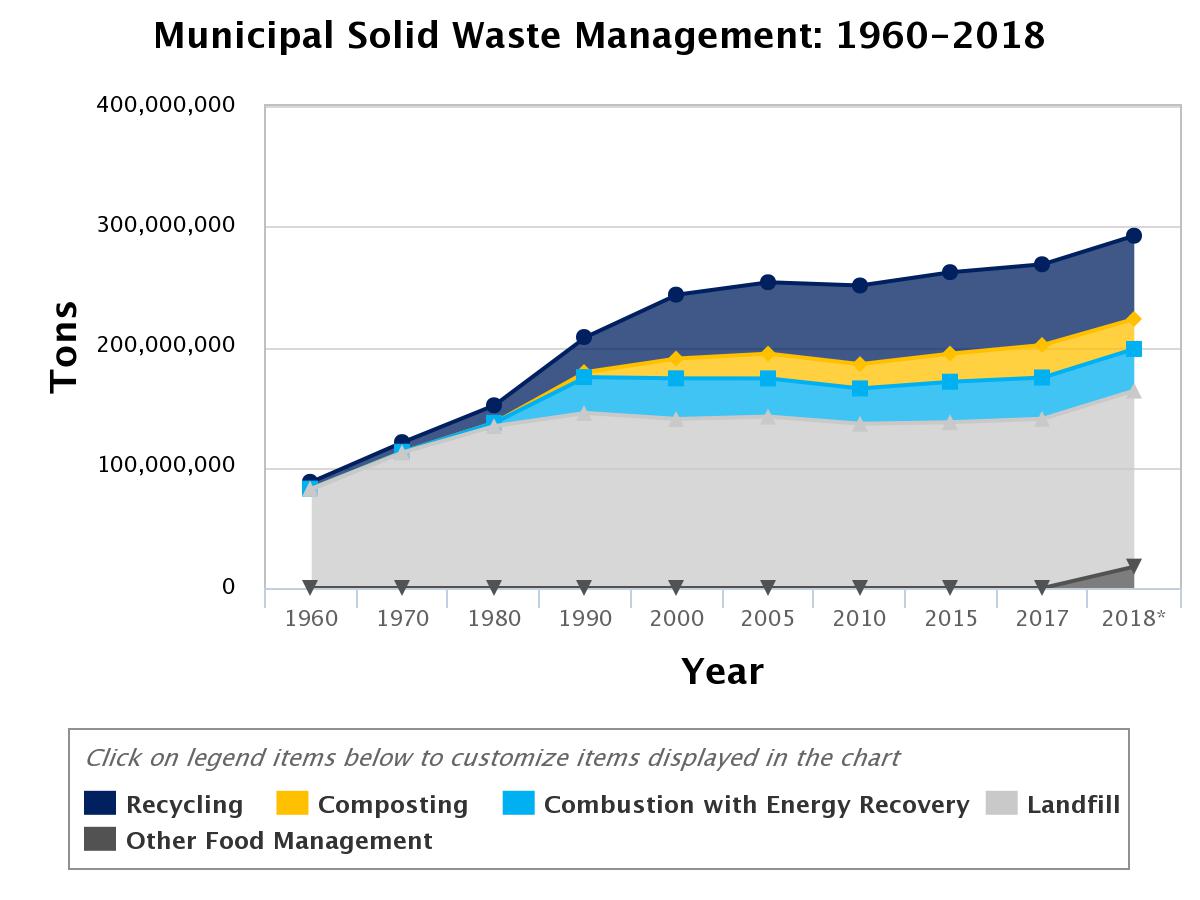

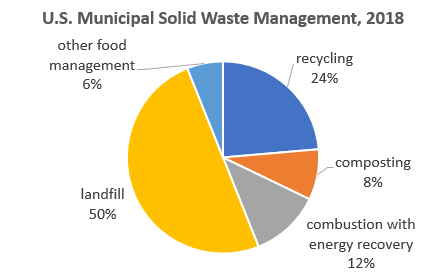

This model requires the constant input of raw natural resources because of the waste and emissions along the way, and because most of the "waste" is dumped in a landfill (and possibly incinerated), and all of this is done primarily with the use of non-renewable energy. This is a major reason why our ecological footprint is so large and we are using natural resources at such a high rate. Globally, only about 12.5% [68] of the primary energy used is renewable (source: BP 2021 Statistical Review of World Energ [69]y). In the U.S., over half of municipal solid waste (MSW) ends up in a landfill. Keep in mind that municipal solid waste is basically household garbage, and does not include construction, industrial, or farming waste, which make up a large portion of the waste stream. All of this adds up to 292.2 million short tons of MSW generated (about 4.9 pounds per person per day, which is up from 4.5 pound per person per day a few years ago), of which about 146 million tons ends up in a landfill, according to the U.S. EPA [70].

Circular Resource Flow

Contrast this with a circular resource flow model, in which there is almost no waste. Any resources that are unused in each step are reintegrated back into the system. Manufacturing "waste" is reused or recycled, as are final products used by the end user. If this could all be run using renewable resources, then much of the pollution would be eliminated as well. In fact, in an ideal circular resource system, the idea of "waste" does not exist. This is the philosophy behind "zero waste" initiatives. Note that because of thermodynamics, there will be some inefficiency, and thus some loss. This is why there will still be some natural resource input required.

It is worth noting that nature utilizes circular resource flow. Recall that it was stated above that the concept of natural resources is anthropocentric. There is no waste in nature - everything is a resource for some other process. Resources move around in continuous flows, and all "waste" is reintegrated back into the system, with the exception of some heat loss that is radiated back to space. All of this is of course driven by renewable energy, and any energy lost to space is offset by energy coming in from the sun. This is why many zero waste (and other sustainability) advocates say that the more we can design human systems to mimic natural systems, the more sustainable those systems will be. As you will see in a future lesson, this is the fundamental philosophy of permaculture.

The Zero Waste Alliance provides an excellent visualization of what such a system could look like. The images below show natural resource flows. The thickness of the flows indicates the relative amount of resources flowing through that part of the system. As you can see, by recovering most of the "waste" throughout, the raw materials flow (at the far left of each diagram) is greatly reduced. Note that the second image shows an idealized flow - there will be some loss due to thermodynamics. Even without thermodynamic loss, some natural resource extraction is required because some resources cannot be directly reused in the manufacturing process.

Waste Management Strategies

The Three Rs

No doubt you have seen some variation of the image below. Most recyclable packaging has a triangle design, which indicates that it is recyclable. You are probably familiar with the phrase "reduce, reuse, recycle," which is hammered home to (most) kids at a very early age in the U.S. The image clearly gives a nod to circular resource use (follow the arrows!). Each term refers to a slightly different way to manage waste. I provide an example of each in parentheses as it relates to a plastic water bottle:

- "Reduce" refers to not creating the item/material in the first place. (Don't buy or use the plastic bottle in the first place.)

- "Reuse" refers to reusing the item (or at least part of the item) for another purpose. (Examples include refilling it with water and using it again, using the plastic bottle to start a seedling or make a small bird feeder. If you make a new, useful product out of it - such as the bird feeder - it is sometimes considered "upcycling.")

- "Recycle" refers to breaking the item down into smaller components and using these materials as a replacement for materials in newly manufactured goods. (A plastic bottle can be recycled and made into a different plastic product.)

However, what most people do not know is that "reduce, reuse, recycle" is actually a priority list. In other words, the best way to minimize the impact of waste is to not use it in the first place (reduce), the second best way is to reuse it, and the third best way is to recycle it. Recycling requires a lot of inputs: inefficient trucks to pick it up and transport it, massive machinery to sort it and break it down, more machinery to produce the new good (often after shipping the raw resource far away), then more energy and resources to distribute the good. This entire process uses energy and generates waste. Reuse is less impactful because it cuts out all of the downstream impacts of recycling, but it does not eliminate all of the upstream impacts that resulted from producing the good in the first place.

While all of this is true, recycling is still much more beneficial than landfilling! The following are some statistics from the EPA [73]. All information was taken from WARM, the Waste Reduction Model. (Click here to download the Excel file [74] and do your own analysis, or just explore the data.) Note that MMBTU is one million BTUs of energy, and MTCO2e refers to one megaton of carbon dioxide equivalent:

| material | reduction energy savings (MMBTU/ton) | recycling energy savings (MMBTU/ton) | combustion energy savings (MMBTU/ton) | reduction emissions savings (MTCO2e/ton) | recycling emissions savings (MTCO2e/ton) | combustion emissions savings (MTCO2e/ton) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aluminum cans | 89.69 | 152.76 | -0.60 | 4.91 | 9.11 | -0.04 |

| glass | 6.9 | 2.13 | -0.50 | 0.53 | 0.28 | -0.03 |

| PET plastic | 50.26 | 31.87 | 10.13 | 2.20 | 1.12 | -1.21 |

| corrugated cardboard | 33.23 | 0.69 | 6.64 | 5.60 | 3.12 | 0.51 |

| newspaper | 36.46 | 16.49 | 7.53 | 4.77 | 2.75 | 0.58 |

Notice that with the exception of aluminum cans, the energy and emissions reductions are always greater when you reduce than when you recycle. Based on what I could see in the WARM spreadsheet, aluminum cans are the only material for which recycling is more impactful. Also note that some materials require more energy to burn than they do to landfill (see the negative numbers), and for ALL materials listed, combustion is worse for emissions than recycling or reducing.

The Circular Economy

The circular economy, as you will see below, utilizes circular resource use.

Living systems have been around for a few billion years and will be around for many more. In the living world there's no landfill; instead, materials flow. One species' waste is another's food. Energy is provided by the sun. Things grow, then die, and nutrients return to the soil safely. And it works. Yet as humans we've adopted a linear approach. We take, we make, and we dispose. A new phone comes out, so we ditch the old one. Our washing machine packs up, so we buy another. Each time we do this, we're eating into a finite supply of resources and often producing toxic waste. It simply can't work long-term. So what can? If we accept that the living world's cyclical model works, can we change our way of thinking so that we too operate a circular economy?

Let's start with the biological cycle: How can our waste build capital rather than reduce it? By rethinking and redesigning products and components and the packaging they come in, we can create safe and compostable materials that help grow more stuff. As they say in the movies, no resources have been lost in the making of this material.