Lesson 2: EM SC 240N Lesson 2 Review

Overview

The purpose of this lesson is for you to review key concepts from Lesson 2 (Fundamental Sustainability Considerations) in EM SC 240N. I strongly encourage you to at least browse through Lesson 2 [1] of EM SC 240N, though that is not required.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- define and provide examples of negative externalities;

- analyze the implications of achieving a steady state economy, and how they relate to ecological footprint.

- identify the pros and cons of energy return on energy invested;

- describe the (in)adequacies of using GDP as a development metric;

- analyze the viability of various development metrics;

- define social and environmental justice;

- identify examples of social and environmental (in)justice.

Lesson Roadmap

| To Read | Lesson 2 Online Content | You're here! |

|---|---|---|

| To Do |

|

|

Questions?

If you have any general course questions, please post them to our HAVE A QUESTION discussion forum located under the Discussions tab in Canvas. I will check that discussion forum regularly to respond as appropriate. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses and comments if you are able to help out a classmate. If you have a question but would like to remain anonymous to the other students, email me through Canvas.

If you have something related to the material that you'd like to share, feel free to post to the Coffee Shop forum, also under the Discussions tab in Canvas.

Externalities

Externalities is one of the more nuanced concepts from EM SC 240N, so I am giving it its own page. This is mostly a summary of EM SC 240N's version.

At this point, I'm sure you are all familiar enough with basic economics to know these three fundamental principles:

- All else being equal (this is known in economics as ceteris paribus [2]), as the demand for something in a market economy increases, the price increases, and when the demand decreases the price decreases.

- All else being equal, as the price of a good increases, the demand decreases, and if the price goes down, demand increases.

- Economic actors buy and sell things based on a cost-benefit analysis. They consider the private utility (the benefit to them) and the private cost (the cost to them) and engage in the transaction if they deem the cost-benefit balance to be in their favor.

The first two are not very controversial - if very few people want something (it has low demand) then it makes sense that companies would need to drop the price to sell it, and if something is in high demand, a company can charge more. Also, as the price of something rises, it makes sense that fewer people would want (or be able to) buy it, and vice versa. (It should be noted that some goods can be "inelastic" to a certain degree, which means that a price increase does not reduce demand by much and/or a price drop does not increase demand by much. Oil [3]can be inelastic under certain conditions, for example.)

The third point makes a lot of sense, too. If I go to buy apples and I go to the grocery store and see two different brands of the same apples (probably Honeycrisp, since my kids are obsessed with them) side-by-side, but one is cheaper than the other, I'll probably buy the cheaper one. The same type of decision-making process goes into most economic decisions that you make, whether it involves clothes, cars, where to go out to eat, which detergent to buy, which cell phone to purchase, and so on. You ask yourself: "Is it worth it to buy this product or that one?" and this is based on the price combined with the perceived value of the good. This lies at the heart of modern economic models.

Thus, the price of something is an essential consideration in how much of it is used, and thereby produced. But how is the price determined? In simplified terms, all of the costs that go into getting the product to the end user should be reflected in the price. For my Honeycrisp apple, the costs of at least the following should be included: the farm (paying for seeds, workers, growing equipment, etc.), the company that shipped the apple to the store (paying for workers, fuel to drive the trucks, people to arrange logistics, etc.), and of course the grocery store (paying workers, electricity bills, paying investors, insurance, etc.). These and any other costs associated with getting the apple to you should be covered. Otherwise, the businesses lose money and won't be able to stay in business much longer. In sum, all of the costs to get the good to you should be included in the price. Seems pretty straightforward, right?

As you may remember, it is not always this simple. All of the apple-related costs included in the price that was noted above are internalized, that is, they are reflected in the price. But can you think of any externalized costs, that is, costs that are not reflected in the price? Examples may include:

- If the apple is not organic, the workers may get sick from the chemicals, which costs them medical bills and lost work.

- If the farm sprays a lot of pesticides, this could harm local bee populations, which in turn reduces other crops that rely on bees to pollinate.

- The fuel used to ship the apples emits CO2, which contributes to climate change, and other pollutants such as particulates, which cause health problems and associated costs.

- The electricity used to power the grocery store may have been generated by burning coal, which has similar impacts to the gas or diesel noted above.

There may also be some external benefits involved with the process of getting the apple to you. Possible examples include:

- The tree absorbed CO2 and some pollutants from the air, reducing the damages noted above. (It should be noted that this would likely be lower than the amount emitted by the truck and the power plant noted above.)

- The trucking job provided enough income for the worker to go to school and eventually get a higher-paying job with better benefits.

- The money paid to the grocery store helped it stay in business, which contributed to the viability of the community around it.

There are many more possible impacts that are not included in the price of the apple. All of these would be considered externalities, as long as they were not included in the cost. The OECD offers a reasonably good, concise definition of externalities:

Externalities refers to situations when the effect of production or consumption of goods and services imposes costs or benefits on others which are not reflected in the prices charged for the goods and services being provided

(Please note that some economists consider anything that happens to someone that was not directly involved in a transaction an externality whether or not that "anything" is included in the price. In this course, we will only consider it if it is not included in the price.) Before moving on, feel free to watch the video below. The most relevant parts are the first 3:20 of the video and 5:06 - 6:22.

OPTIONAL video

Externalities occur when costs or benefits accrue to a person, or persons, who are not involved in the decision-making process. Note that externalities can involve either third-party costs (this would be a negative externality) or third-party benefits (this would be a positive externality). Let's address each of these in turn.

Negative externalities occur when a decision or activity imposes costs on anyone not involved in making that decision. Think of it this way: every decision involves some cost to the decision-maker; that's the private cost of your choice. But sometimes the decision imposes costs on others as well, which would be the external cost. Social cost, then, is the total cost to all members of society, or the sum of the cost to the decision-maker (which is private cost), and to others (external cost). What this means is that if a decision imposes any kind of external cost, then the social cost will exceed the private cost.

Think about this: do you think that too many people use their cell phones while driving, or too few? Well, why do you think that is? The answer lies with this notion of externalities. Look at it this way: when you're deciding whether or not to get on your cell phone while you're driving, what are the private costs, i.e. the costs to you, the decision-maker? Perhaps the cost of buying a cell phone in the first place? Or maybe the minutes you'll be using, or the cost of sending a message? It might even occur to you that you're increasing the likelihood of you getting into an accident. Now, are there any costs to other people, people who have no control over your decision to use your phone while behind the wheel? What about the increased risks to them? Or even just the annoyance of you driving like an idiot because you're on the phone? These are the external costs or the costs you impose on others with your behavior.

In the end, this discrepancy between the cost to you and the cost to society (which is the sum of the private and the external cost) leads to overproduction, if you will, of people driving while on their cell phones. Why? Because we’re all rational decision-makers – using the cost to us and the benefits to us to make our decisions. Very rarely do you find someone who includes costs to others when weighing a private decision. Essentially, you make the decision to be on the phone while driving because you consider only part of the cost - the cost to you. With negative externalities, because the private decision is based on costs that are too low, from society’s standpoint, the behaviors, or products, are overproduced from society's view.

This market failure provides a role for the government to correct the market, i.e., bring the production back to the socially optimal level. In the case of cell phones, this is most often done by putting laws in place that ban such behavior while driving and have hefty fines attached if you're caught. This effectively raises the cost of engaging in such behavior and thus decreases the amount of the behavior that occurs. The same idea would apply to, say, a steel factory. There's a certain private cost of producing steel (I’ll assume that on the benefit or demand-side, private and social are the same for now), but the production of steel also results in pollution, a cost to others in society. This means that the marginal social cost is greater than the marginal private cost. Left to its own devices, the steel market will be based on private costs and private benefits, yielding the price and quantity associated with equilibrium E1. What would society rather see? The socially optimal outcome would be based on social cost and social benefits, or equilibrium E2. Notice, this means society would like to see less production, meaning less pollution, and would be willing to pay a higher price to do so.

This is where the government comes in.

What is the government solution to a negative externality? Simple! Get the decision-maker to internalize the external effect. Since the problem arises from the decision-maker using costs that are too low, you need to somehow impose some additional cost, so the decision becomes based on level of social cost. This could be done by way of taxes, fines, regulation or cleanup fees. Or, in the case of pollution, there’s now a market for credits that allow you to pollute. If you're a clean producer, you’ll have unused credits you can sell which is an incentive for cleaner production. If you create a lot of pollution, you’ll need to acquire extra credits to continue producing, which is also an incentive to cut back on pollution production.

What about positive externalities? Just as you can make choices that impose costs on others, you can also make choices that result in benefits to others. If this is the case, then social benefits equal the private benefits, or benefits to the decision-maker, plus external benefits, or benefits to others. In the case of a positive externality, social benefits exceed the private benefits. Take education, for example. YOU decided to continue your education; why is that? What are the benefits to you of making this decision? It might just be the love of learning, or because you know that education means a better, higher-paying job in the future. But what about society? Society as a whole benefits from having a better-educated populace; highly educated, highly-skilled workers tend to be innovators, which helps keep our economy moving forward. All of this is good except for the fact that, in a free market, education will be underproduced -- this is true of any positive externality.

Why? Because the private decision-maker doesn't see the full benefit of education that society sees, so not as much education is produced. For the consumer of education, there's a certain private benefit (I’ll assume private cost and social cost are going to be the same). Decision-making based solely on private costs and benefits results in equilibrium at E1. Society as a whole sees a greater benefit; if the equilibrium were based on social costs and social benefits, equilibrium would occur at E2. Society desires a greater level of education, and is willing to pay more to achieve it. From a social standpoint, in a free-market, education will be underproduced. What's the government solution to a positive externality? Well, get the decision-maker to internalize the external effect. Sounds familiar, doesn't it? Except that with the negative externality, we had to try to get the decision-maker to see higher costs; with a positive externality, the government needs to somehow make the decision more beneficial to the private decision-maker. In the case of education, the government may provide grant money, low-interest loans, or tax credits in order to provide added incentive to get more education.

As noted in the video, there are usually external costs and/or external benefits to transactions. External costs and benefits are borne by people or other entities that had no input on the transaction and were not fully included in the price. A negative externality occurs when an external cost occurs, and a positive externality occurs when an external benefit occurs.

Sustainability Implication

There are a few important sustainability implications of externalities:

- Negative externalities are very common, and often impact sustainability. Pollution is a prime example of this. It is rare that all of the costs of pollution are included in the price of something, whether it is mercury, sulfur dioxide, or particulates emitted from a power plant, CO2 emitted from a car's tailpipe or fertilizers that run off of farms and cause dead zones. These can all have major negative sustainability impacts.

- Negative externalities are overproduced because they make the price lower than it should be. If the negative impacts of climate change were included in the cost of coal-fired electricity, for example, the cost of coal-based electricity would be higher and the demand for it would diminish.

- Positive externalities are underproduced because they make the cost lower than it should be. If all of the benefits of say, education were included in its price, the price would be lower and thus in higher demand.

- In a broader context, economics plays such an important role in modern society that externalities have become a major problem.

In sum, externalities are by definition not included in the cost of goods. Positive externalities, which are usually good for sustainability, do not occur as often as they should because the benefit is not included in the price. Negative externalities (which are more common, by the way) happen more often than they should because their cost is not included in the price.

The Social Cost of Carbon

Without getting into the specifics about the probable causes of climate change (that will be covered in the next lesson), let's take a look at climate change as an externality. As you will see in the next lesson, if the climate continues to change, the impacts will be overwhelmingly negative. Quantifying these costs is an active area of research, but many countries - including the U.S. - have placed an "official" cost on the emission of carbon dioxide (this is used to calculate the cost of new legislation). Under the Obama administration, the U.S. federal government used a social cost of carbon (SCC) of $39 per tonne [4]of carbon dioxide. (Not surprisingly, the Trump administration has proposed to lower this significantly.) A 2015 study out of Stanford University [5] found that the U.S. grossly underestimated the SCC and that it should be closer to 220 dollars/tonne. In 2013, major corporations integrate the cost of carbon emissions into their projects [6] (between 6 dollars and 60 dollars/tonne), though they use some different considerations than SCC, and by late 2016 hundreds of companies [7] worldwide had integrated SCC internally.

Summary

There is a lot of material to these points and it is very important, so here is a summary of the key points:

- An externality is a cost or benefit of the production or consumption of a good or service that is not included in the private cost/benefit of that good or service.

- An external cost (e.g. pollution) not included in the price is a negative externality. An external benefit (e.g. education) that is not included in the price is a positive externality.

- If all external costs and/or benefits are included in the price, then most economists believe that no externality has taken place.

- Goods and services with negative externalities tend to be overproduced, meaning that more is produced than is socially optimal. This is because the private cost of the good/service is less than the total (social) cost, i.e., it is cheaper than it should be.

- Goods/services with positive externalities tend to be underproduced because the total (social) benefit is higher than the private cost, i.e., it is more expensive than it should be.

- The direct short-term external costs of energy generation can be significant, due to health problems and other issues. In other words, if external costs were included in the price of fossil fuels, they would be more expensive. However, in some emerging economies, these external costs may be overcome by the positive benefits of having more energy.

- Climate change is considered a negative externality because the impacts of emissions are felt by people that did not cause the emissions. Most of these costs are in the future.

- The social cost of carbon (SCC) is an attempt to quantify the external cost of emitting CO2. This is very difficult to do but has been quantified in terms of dollars per tonne of emissions. By using dollar per tonne, the cost of a kWh of electricity, a gallon of gasoline, ccf of natural gas, etc. can be calculated.

- The intent of using SCC is to integrate the external cost of carbon emissions into the price of things that cause these emissions. This would make them more expensive, but could more accurately reflect the true cost.

Ecological Footprint

I'd like you to consider these two basic truths:

- When a resource has a limited capacity to be replenished, if it is harvested faster than it is replenished, it will diminish.

- When pollution is emitted faster than it can be absorbed, it will accumulate in the environment.

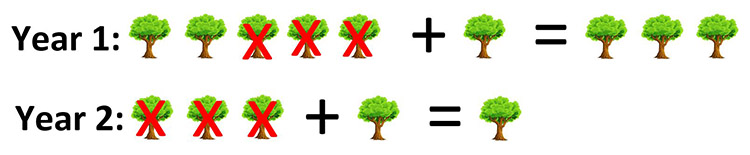

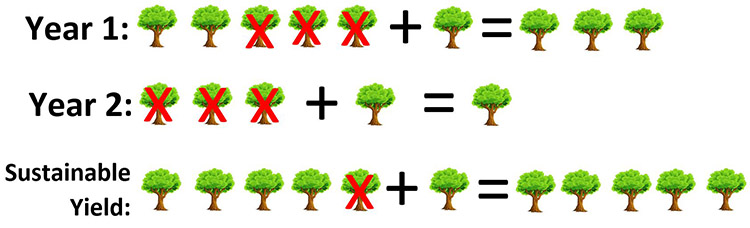

Just as a business that loses more money than it makes runs a deficit, when humans overuse the capacity of the earth to replenish resources, it could be said that these places are running an ecological deficit. In this scenario (see the image below for an example), our stock of natural resources will diminish.

It is relatively easy to determine the number of trees (or other plants) that a farm can grow in a year. The earth, of course, provides a lot of other natural resources that are useful and/or important for humans (absorbing CO2, providing oxygen, providing food, replenishing the soil, etc.). Combined, the amount of these resources sustainably provided in one year can be considered one "earth's worth" of resources. If we could figure out this "one earth" and compare it to how many of these resources we use, we could determine if we are losing or gaining ecological capacity. This is where the concept of ecological footprint comes in.

Optional Video

Feel free to watch this short video from Mathis Wackernagel, who originated the concept of ecological footprint. He is currently Executive Director of the Global Footprint Network [9], which specializes in calculating ecological footprints.

The Ecological Footprint: Accounting for a Small Planet

We have been the most successful species on this planet. Two hundred years ago, nobody could have imagined that kind of lives we are living today: the cities we have been able to construct, the technologies we have been able to create. And so we are asking ourselves, how will we be able to maintain the success in the future? Since the end of World War Two, we have more than doubled population, and we are consuming far more per capita. In the last century alone, we are now consuming tenfold the energy what we did hundred years ago, and we are recognizing that the planet is getting awfully small.

If we just compare, you know, how successful we have become as a species. We as a species together with our cows and pigs, we are about 97 percent of the biomass of all vertebrate species. But only about three percent are wild species, so we have been able to dominate the whole ecosystem of the planet. Now that may be a success but its success also had its cost: that the planet is getting awfully small. That’s why we have developed the ecological footprint to start to measure how big are we compared to the biosphere, how can we actually use our ecological assets more effectively to live well on this planet. Now the ecological footprint is a very simple tool. It's a tool like a bank statement that tells us on the one hand how many resources do we have that renew itself, thanks to the biosphere that is powered by the sun. And how many do we use, and then you can see to what extent we are actually dipping into the overall capital or to what extent we're really living within that interest that nature provides us.

If you want a real simple and effective model of how do the economy operates, just take the cow. Because everything that enters the cow as food will leave again. Very similar to an economy, a cow also produces a value-added, the milk. The milk, too, whether you consume it or not, becomes waste.

So a farmer knows how much area, how much pasture, how much cropland, how big of a farm is necessary to maintain his or her cow herd. Now the same way we can see how much area is necessary to support me or to support our cities, to support our economies, to support the world as a whole, all humanity - to maintain all the resources we consume and to absorb the waste - that's what the ecological footprint measures for you.

This all points to the importance of ecological footprint. Ecological footprint can be defined as follows:

"Ecological Footprints estimate the productive ecosystem area required, on a continuous basis, by any specified population to produce the renewable resources it consumes and to assimilate its (mostly carbon) wastes."

~Jennie Moore and William Rees, "Getting to One-Planet Living", p. 40

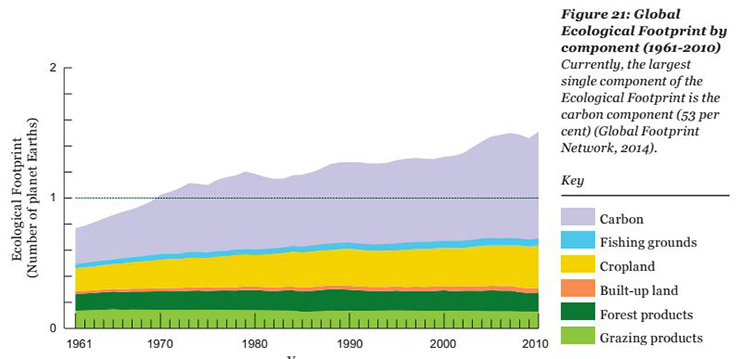

The beauty of ecological footprint is that it provides a specific area of land and water that must be used to sustainably provide the resources necessary to support a person or population. (It is impossible to know the exact area needed, but we can derive a good scientific estimate.) From a sustainability perspective, it follows that if a person or population is using more land/water area than they have available to them, they are living unsustainably. On a global scale, if humans are using more resources than the earth can sustainably provide (one earth), then they are living unsustainably, and the earth's capacity to provide resources will diminish. This is where we are right now, as you can see in the image below.

Click here for a text description.

The key points related to ecological footprint are as follows:

- We depend on the earth's natural resources for survival. If we diminish the ability of the earth to replenish natural resources through time, we are compromising our ability to survive.

- We only have one earth, and this one earth can only regenerate so many resources in a given year (produce food, filter water, pull carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, etc.). If we compare the number of resources that are provided each year be the earth (one "earth") to the amount we use (our global ecological footprint), we can determine whether or not we are living within our ecological budget.

- If our global ecological footprint is one earth or less, we are living sustainably from the perspective of ecological footprint (note that this says nothing about the quality of life of people on the planet or the survival of specific species).

- If the ecological footprint is greater than one earth, then the stock of biocapacity will diminish over time. If biocapacity diminishes, eventually ecosystem collapse will occur, and ultimately societal collapse as well.

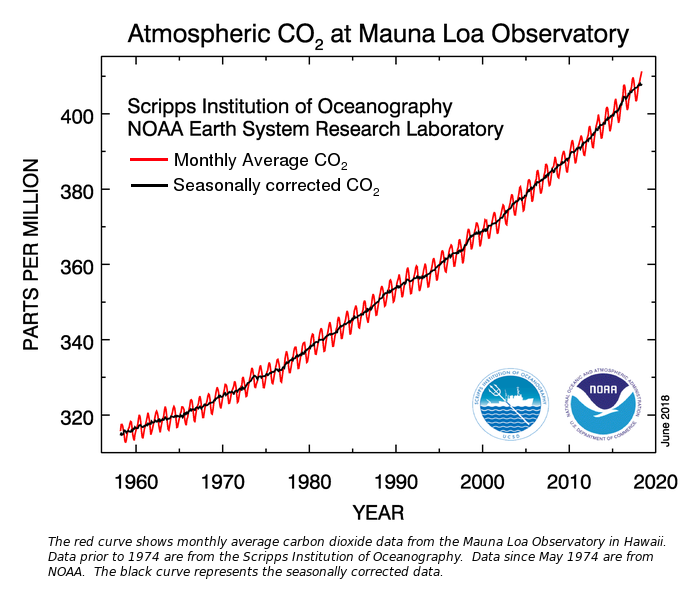

Overshoot and Collapse

Finally, I'd like to remind you of the concept of overshoot and collapse. Overshoot and collapse refers to a situation in which a critical threshold has been surpassed, but the full negative impacts of crossing that threshold have not yet become apparent. By the time those impacts have become apparent, it is too late to remedy the situation. (Feel free to read the description of what happened on St. Matthew Island [11] cited in EM SC 240N.) Humans are by-and-large good at responding to feedback, so when a situation occurs that does not provide immediate feedback, we tend to have difficulty addressing it. Climate change is unfortunately a prominent example of this because by the time the worst impacts have become reality, it will be too late to do anything about it unless we can rapidly remove the greenhouse gases from the air.

Figure 2.4: The concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has been directly measured since 1958, increasing from just above 315 parts per million (ppm) in 1958 to over 400 ppm currently. At a fundamental level, this increase is due to more carbon being emitted into the atmosphere than pulled from it.

A chart showing the global carbon dioxide increase since 1958. The line gradually increases from 315 parts per million (ppm) in 1958 to over 410 ppm in August of 2018. Seasonal fluctuations occur, but only a few ppm each year. The graph shows a steadily increasing rate from 1958 to 2018.

EROI and Sustainable Growth

Energy Return on Energy Invested

Energy return on energy invested (EROI) is a fairly straightforward concept. The following summaries key concepts and terms regarding EROI:

- Almost all end-use energy used by humans requires some energy to gather. Drilling rigs must use energy to drill for oil and natural gas, all of the components of the rigs require energy to manufacture, oil refineries use energy to turn oil into gas and other products, energy is required to transport oil and gas through pipelines, and so on. Renewable energy is no different: The silicon for solar cells must be mined and processed onto wafers, the plants that manufacture solar panels require energy to run, solar installers transport panels using vehicles, and so on. All of the energy used in providing end-use energy is considered embodied energy.

- Net energy is the difference between embodied energy and end-use energy (end use energy - embodied energy = net energy).

- By dividing end-use energy by embodied energy, you get EROI. Thus, EROI is the ratio of how much energy you get out of a process to the amount of energy required to obtain that energy. So an EROI of 4 indicates that you were provided 4 times as much energy as you used. An EROI of 100 means that you have 100 times the amount of energy that was used. And so on.

Here is the equation. (Note that "quantity of energy supplied" is the same as end-use energy and "quantity of energy used in supply process " is the same as embodied energy.):

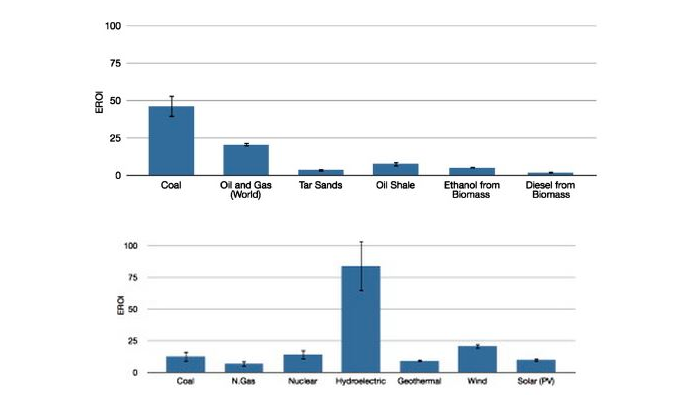

The images below provide a snapshot of sample EROIs of various fuels provided in a peer-reviewed article by Hall, Lambert, and Balogh called "EROI for different fuels and the implications for society [14]."

- Above 75 EROI: Hydroelectric

- Near 50 EROI: Coal

- Near 25 EROI: Oil and Gas (World), Wind

- Approximately 10-12 EROI: Oil Shale, Coal, Nuclear, Geothermal, Solar (PV)

- Near 0 EROI: Tar Sands, Ethanol from Biomass, Diesel from Biomass, Natural Gas

Why is EROI important? One of the main reasons is that EROI is more indicative of the true net energy benefit of various fuels than the end use. It takes about the energy from 1 barrel of oil to extract 20 actual barrels of "traditional" oil (it has an EROI of about 20:1), but the same amount of energy, when used to extract tar sands oil, results in only about 4 actual barrels. In other words, EROI indicates that you get about 5 times the amount of energy from traditional oil than from tar sand oil given the same amount of input. A very interesting finding in the Hall, Lambert, and Balogh article is that oil discovery in the U.S. has decreased from 1000:1 in 1919 to only 5:1 in the 2010s, meaning we get 100 times less energy now than 90 years ago! (Essentially, we have extracted most of the "easy to get" oil and do things like deep sea drilling now.) Getting ethanol from corn (recall from Lesson 1 that this is the U.S.'s primary source of biofuel) can require almost as much energy in as energy you get out, depending on how it is grown and processed.

EROI can help policymakers and others decide which energy source is a more efficient use of energy resources. In the context of this course, it is a particularly important consideration for non-renewable resources, because it indicates the net energy benefit of the sources.

One extremely important final thing to note: EROI only describes energy use. It says nothing about the other important impacts and factors. For example:

- Total energy available is an important consideration - if we can get something really efficiently (high EROI), but there is not a lot of it, then that may not help very much.

- Coal has a relatively high EROI but is the most polluting energy source we use.

- Hydroelectricity has a very high EROI, but if done the wrong way can have negative impacts as well.

- Tar sands, on the other hand, have both a low EROI and a very negative impact on the environment.

- Coal (like oil, natural gas, and nuclear) is non-renewable, and thus limited. (Though we are unlikely to run out any time soon for most of these, as you'll see in a future lesson.)

- All resources are available in limited locations and can be difficult to transport efficiently. Local/native resources may be more logical to use, even if they have a relatively low EROI.

In short, EROI is only one consideration to be made.

Sustainable Growth?

If you listen to the news, pay attention to politics, or read about business activity (no matter where you live in the world), you know that it is taken as almost a given that economic growth is good, and should be pursued ad infinitum. But you may recall from EM SC 240N that not only is growth not always good, but permanent economic growth is impossible on a finite planet unless it can be done in such a way that the total amount of natural resources on Earth remains the same year after year. In other words, as stated by Herman Daly:

"An economy in sustainable development...stops at a scale at which the remaining ecosystem...can continue to function and renew itself year after year" (Herman Daly, "Sustainable Growth, an Impossibility Theorem," p. 45)

This is one of the main points of Herman Daly's seminal article "Sustainable Growth, an Impossibility Theorem." Feel free to read through this reading, which is posted in Canvas. The following are some other important points from the article:

- Daly is careful to point out the difference between growth (getting "bigger") and development (getting "different"). The economy and society can develop forever, but cannot grow forever. A developing economy is not stagnant, even if it is not growing. An economy cannot grow forever, however, because it is a subset of the Earth, and is subject to the physical limitations that the Earth's biocapacity provides.

- He states from the outset that "sustainable growth is impossible" (p. 45). Simply put, as long as the economy is based on the unsustainable use of natural resources, economic growth cannot be sustained indefinitely.

- Sustainable development is possible only if it exists within a system that is "maintained in a steady state by a throughput of matter-energy that is within the regenerative and assimilative capacities of the ecosystem" (p. 45), i.e., we can only use resources at a rate no faster than they can be replenished, and cannot emit wastes any faster than they can be safely absorbed into/assimilated by the natural environment.

- He notes that growth has "almost religious connotations of ultimate goodness" (p. 45). This was addressed above.

- On p. 46, he is clear that one of the primary goals of the economy should be to alleviate poverty, but that simply growing GDP (or GNP) will not make that happen without some guidance and/or policies.

- He offers a few relatively straightforward policy solutions on pp. 46 - 47:

- Tax resource extraction and using the money to reduce income tax, particularly at lower income levels. (Side note: This is referred to as a revenue-neutral tax because all of the revenue is given back to the people, not the government. A revenue-neutral carbon tax has been proposed by more than one bipartisan group. See this link to the Citizens' Climate Lobby [16], and this one to the Climate Leadership Council [17], if you are interested in learning more.)

- "Renewable resources should be exploited in a manner such that: (1) harvesting rates do not exceed regeneration rates, and (2) waste emissions do not exceed the renewable assimilative capacity of the local environment" (p. 47). Sorry to sound like a broken record, but these should sound familiar.

- Finally, he proposes that: "Non-renewable resources should be depleted at a rate equal to the rate of creation of renewable substitutes" (p. 47). For example, for every 1,000,000 BTUs of fossil fuel used, we should find a renewable source of 1,000,000 BTUs. He suggests supporting this by taxing non-renewables and using the funding to develop renewable substitutes.

All of the above summarizes the concept of the steady state economy.

Optional Video

Feel free to watch a video (5:07) featuring Herman Daly, himself, discussing the steady state economy:

If we start with the total system, the Earth, then it's fairly clear that the Earth is more or less a steady state - in the sense that is not increasing in aggregate mass; it is not increasing in surface area. The rate of inflow of solar energy is more or less constant. The rate of outflow of radiant heat energy is more or less constant. – at the same amount, same amount of energy.

If that weren't the case, then temperatures will be going up. The import from outer space of materials and the export to outer space of materials are roughly equal - I mean both negligible, and usually involuntary in any case. So, the Earth as a whole, in its behavior mode is a steady state. So as the economy becomes a larger and larger subsystem of the Earth, then more and more it has to conform to the behavior mode of the whole of which it is an ever-larger part.

So in the limit, I mean the economy takes over the whole Earth, well then it’s got to be a steady state because that's the way the Earth is. And then I think it needs to approximate a steady state long before it hits that limit. And so I think that's kinda the long run idea of steady state.

Now the idea, I think there are limits, you know, long before the macroeconomy hits that physical scale limit. Long before that happens, we experience the cost of growth rising faster than the benefit. Because we're sacrificing natural services that are more important than the production benefits that we gain.

I mean, you would expect this to be a normal consequence of classical economics - the law of diminishing marginal utility: you satisfy your most pressing wants first. So, you are going to run out of important things that you need. And the Law of increasing marginal cost: you do the easiest thing, you have access to the easiest resources first, so the cost will go up there.

So, you know, what we need is to be good economists, in the sense that we measure costs and benefits and are sensitive enough to recognize the economic limit to growth, to stop when growth becomes un-economic and not be so dumb or so insensitive that we have to crash headlong into biophysical limits and really get smashed.

As John Stuart Mill said, who was the classical economist who gave the fullest exposition and the most favorable exposition of the idea of a steady state, which they referred to as a stationary state, but it meant basically the same thing… He says it by no means implies any stationary state of human welfare. There will be as much room for moral and ethical and technical improvement as there was in a growth economy. And much more likelihood of it happening, in a way, because when you close off physical growth then the path to progress has to be moral and technological and intellectual and informational. You’ve switched the path to progress from this physical more and more stuff to a qualitative improvement of the same amount of stuff.

And, how far we can go in that direction? Uh, you know, who knows, but regardless of how far, why not, so we're gonna have to go in that direction.

So, let’s do it, and if we're lucky it won't be all that costly. It will be a great deal of moral improvement because I rather expect that we will…it will go well in that way because the material, the attempt to satisfy our wants by material growth was a little bit like scratching in the wrong place. You know, you’ve got a real itch, but you are just clawing somewhere and it doesn't help.

So at least I think this will help us to scratch in the right place if we devote our attention to moral and technical progress.

Free Market Environmentalism

It should not be difficult to recognize that humans are subject to the physical constraints of planet Earth. But how we make sure that we do not exceed our limit to the point of collapse (e.g., overshoot and collapse mentioned previously) is something that is debated, even by people with seemingly the same end goals. There is a branch of environmental (well, it's primarily economic) thought that is based on the power of free markets to most efficiently manage resources. This is often called free market environmentalism (FME). Those who advocate for FME believe that free markets (economic systems that are free from government regulation) are the best way to solve environmental problems. And, just as important, they believe that the government is much worse at managing resources than the market. This article from the Library of Economics and Liberty [18] (a free market think tank) summarizes the school of thought pretty well.

As outlined in this article, this school of thought rests on three assumptions in order for markets to work for any environmental good (e.g., a forest, clean water, clean air, etc.): "Rights to each important resource must be clearly defined, easily defended against invasion, and divestible (transferable) by owners on terms agreeable to buyer and seller" (source: Library of Economics and Liberty [18]). In other words, if a piece of property has:

- clear ownership, and

- those ownership rights are defensible in court (or elsewhere), and

- it can be bought and sold freely, it will be preserved.

I would add that (4) the author (and this is typical of FME) also assumes that the owner of the property is motivated to protect the property in anticipation of future profits.

For example, if I own a lake and someone pollutes it, if the courts are just, the polluter will end up paying me because (s)he compromised my ability to enjoy my property. If these conditions are known, then the polluter, in theory, will decide not to pollute in order to avoid the extra cost. As you can see, all of this relies on using money as the motivating factor.

This is a very sound argument as long as those conditions are met, at least in terms of environmental protection. This situation, and variations of it have been proven effective in a wide array of applications. It worked for water conservation in the Western U.S. [19] And here are a number of case studies [20] demonstrating that these principles can work.

But what if those four conditions are not met? With climate change, a fundamental question is: "Who owns the atmosphere?" (The answer: no one does.) If there is no clear ownership, the system may not work. Let's go back to my lake that got polluted, and think about a few plausible scenarios.

- What if it was impossible to prove where the pollution came from? If it was airborne pollution that is impossible to trace, I am out of luck. I have no one to sue. This is, unfortunately, the case for a lot of types of pollution.

- What if I can make more money destroying my lake than preserving it? I could fill it in and build an apartment on it. Or sell it to a chemical company to use as a dumping ground. If I place a certain economic value on my lake, then it stands to reason that I would be willing to destroy it if I could make more money by doing so. I could use the money to move on and buy more property. The case studies noted above hinge on a party or parties agreeing that conservation is necessary.

- This type of system is based on the perceived value being the real value, which can also cause problems. Biodiversity (which we will go over in the coming lessons) is something that very few people place value on but is essential for human survival. Also, there are certain goods that are nearly impossible to accurately price, even using Willingness to Pay analysis. Negative impacts on future generations is one that is particularly sticky in this regard. (Remember intergenerational equity?)

- Finally, by basing everything on money, those without money will have less access to the resource. If you recall from Lesson 1, this fits squarely with one of the fundamental sustainability principles (social equity). If I charge people a lot of money to fish in my lake, that may help preserve the lake, but at the expense of equity.

This article from the Property and Environment Research Center [21] - also an advocate for free-market environmentalism - goes over a few of these and other examples where the system breaks down.

Food for Thought

It should be apparent at this point that humans cannot continue to live beyond the planet's ecological means and expect to survive. We have one "Earth's worth" of replenishable resources, and as we diminish that stock of resources by using them faster than they can be replenished and/or emit wastes faster than they can be absorbed, we reduce our ability to survive. Many different ways to achieve such a steady state economy (or something close to it) have been posed. Some people, such as Herman Daly, propose using taxes, incentives, and other policy-based solutions. Others advocate unleashing the power of economic markets to solve the problem, mostly through privatization. Please note that even the most ardent advocates [22] of regulation recognize that markets are extremely effective and efficient at allocating resources, but that they do not work well under a number of circumstances, e.g. when negative externalities artificially lower prices, and when impacts are not immediately felt (e.g. with climate change). Because of the massive externalities - particularly with regards to intergenerational equity, i.e. the impacts of today's actions will be felt by future generations - even free-market proponents recognize that it is not a problem that can easily be solved by markets.

Hopefully, by reading through and thinking about these issues, you will not simply take for granted that "growth is good," regardless of the circumstances or consequences. Daly himself concedes that growth can be good as long as it helps alleviate poverty, but ultimately we must reach a steady state economy if we are to establish a sustainable society.

Development, Quality of Life, Social/Environmental Justice

The Inadequacy of GDP

GDP is the most oft-used metric to indicate how a country "is doing," economically speaking. But it is also widely used as a general indicator of how a country's people are doing. There is some usefulness to this, as you will see below. But GDP obscures a lot of possible problems (economic, social, environmental, etc.), and does not indicate all of the good things about society. In short, there are some things that are good for GDP that are bad for people, and there are some things that are good for people that are not necessarily good for GDP. This problem was eloquently described by Robert F. Kennedy in 1968. It is as relevant today as it was 50 years ago. Hopefully, this will give you some pause when you hear the latest GDP numbers as an indicator of how well a country is doing.

Too much, and for too long, we seem to have surrendered personal excellence and community values in the mere accumulation of material things. Our gross national product now is over 800 million dollars a year. But that gross national product - if we judge the United States of America by that - that gross national product counts:

- air pollution and

- cigarette advertising

- and ambulances to clear our highways of carnage.

It counts special locks for our doors and the jails for the people who break them. It counts the destruction of the redwoods and the loss of our natural wonder in chaotic sprawl. It counts napalm and it counts nuclear warheads and armored cars for the police to fight the riots in our cities. It counts Whitman's rifle and Speck's knife, and the television programs which glorify violence in order to sell toys to our children.

Yet the gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education or the joy of their play.

It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debates or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wits nor our courage. Neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country. It measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile, and it can tell us everything about America except why we are proud that we are Americans.

Quality of Life

Quality of life is another one of those terms that is thrown around liberally but has no specific definition. We all want a high quality of life, but what does that mean exactly? I am not here to settle the debate, but I do like the definition from this website [23]: Quality of life is "the extent to which people's 'happiness requirements' are met." I'd add the term "satisfaction" in there as well, as in "are people's 'satisfaction' requirements met?" Nothing is universally regarded as necessary for happiness or life satisfaction. For example, I have friends who LOVE to hunt for deer and will sit for hours in a tree stand in the freezing cold, silently waiting for one to walk by. I can think of a lot of things that I'd rather do than that. But to them, that is an important part of their quality of life. Nothing wrong at all with that, by the way - it's just not for me.

Hunting is something that is obviously not universally required for a high quality of life. But I'm sure there are thousands, if not millions, of people who count it as important. But if you think about it, there is nothing that everybody loves to do, so it wouldn't matter which activity I used as an example. So, if we want to measure the quality of life, how do we do it?

Development

Before we move on to the discussion of how to measure the quality of life, it is important to consider the concept of development. Development refers to how well the people in a country are doing, as in "How developed is country X?" or these are the "underdeveloped countries." Please note that many people (myself included) take issue with categorizing an entire country full of people using a single western-centric, judgmental term, which is why I use terms such as "(less) industrialized" or "high/low income" countries. These terms are objective descriptors, not judgments. Regardless, GDP and/or GDP/capita play primary roles in defining the level of development of a country, as do things such as having modern economic and political systems. There is some validity to this, but as RFK and others point out, GDP is not everything! A few more aspects of development worth pointing out (some of which are described in this reading from the World Bank [24]) are as follows:

- GDP/capita indicates nothing about the distribution of wealth. It is possible (e.g., in Equatorial Guinea) to have a high GDP/cap but to still have a large portion of the population having very little access to resources.

- Having a relatively high GDP does provide the potential for development - it is difficult to thrive in the modern world without some money, after all - but does not mean that all people have access to health care, education, and other things that contribute to a high quality of life. Generally speaking, having a higher GDP indicates that the people in a country are doing relatively well, but this is not always the case.

- Related to the previous point, GDP should not be misconstrued as the goal of development. High quality of life should be the "end," and economic development is only one means to that end.

- It is important to keep in mind that unless the economy is structured in an environmentally sustainable manner, the ability to provide a high quality of life will diminish over time.

Quality of Life Metrics

There are many possible factors that contribute to the quality of life, or lack thereof. So how do we measure quality of life? For that, we need a quality of life metric. These are often referred to as development indices. Recall from Lesson 1 that it is important to be able to measure aspects of sustainability. Development indices are one aspect of this.

There are two approaches to this:

- On the one hand, we could try to directly measure the quality of life itself.

- Conversely, we could try to quantify the conditions that lead to a high quality of life.

There have been many attempts to do the latter and a few that have tried to do the former. It would be impossible to research all of these, but some of the most used and/or most useful ones are listed below. The first two (HDI and Inequality-Adjusted HDI) measure things that lead to a high quality of life, the third one (Happiness Index) attempts to measure it directly, and the last one (Happy Planet Index) is a mixture of the two plus ecological footprint. Please note that even the best metric cannot create a full picture of development, however it is measured. Even the most "developed" country will have people who are living in poor conditions. Also, keep in mind that this is not a comprehensive list of development indices.

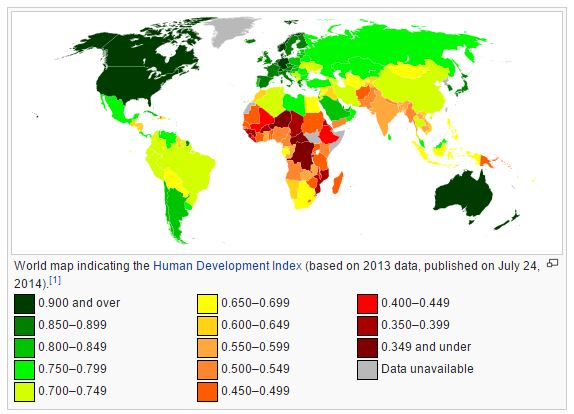

Human Development Index (HDI)

The Human Development Index is the most well-known quality of life metric. It was created by the United Nations (UN), who assesses it every year. It measures three things to determine quality of life, as you will see below: living a "long and healthy life, being knowledgeable, and hav(ing) a decent standard of living." The HDI scale goes from 0 (the worst possible) to 1 (the best possible). Feel free to read the description from the UN here [25], and browse through the ratings here [26].

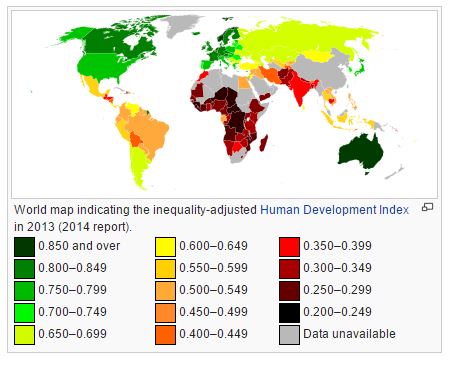

Inequality-Adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI)

The UN also publishes Inequality-Adjusted HDI (IHDI), which takes HDI and discounts it according to how equally the individual development metrics are spread across the population. If the Inequality-Adjusted HDI is lower than a country's HDI, then there is some inequality. As noted by the UN, the IHDI represents "the loss to human development due to inequality." The more inequality, the more the HDI score drops when adjusted for inequality. Note that the pattern in the map below is similar to the HDI map above, but the raw values are a little bit lower. Feel free to read more about IHDI here [29].

World Happiness Index/Report

The World Happiness Report asks people to indicate on a scale of 0 - 10 their quality of life now and their expected quality of life in the future (see World Happiness Report details here [32], if you'd like). The basic premise behind this is that if you would like to determine how happy or satisfied someone is with their life, just ask them. This is a type of self-reported quality of life and results in a score of 0 - 10. This is sometimes referred to as the Happiness Index.

Pretty simple, right? Though it does beg some important questions. For example, if someone lives a short life with little education, but they are happy, does it matter? What about someone that has very little freedom, but is happy? What if they have almost no money, but are happy? What if others in their country lead much "better" lives, but they do not know it? I do not have the answers, but they are important questions to think about.

Happy Planet Index

Last but not least, we have the Happy Planet Index. This index takes into account both well-being (they use the same metric as the Happiness Index), life expectancy (like the HDI), and inequality of outcomes. The higher your well-being and life expectancy, the higher your score. Inequality is expressed as a percentage, with a higher percentage meaning more equal outcomes. But what is unique about the Happy Planet Index is that it divides by the ecological footprint, so a higher ecological footprint will result in a lower score, and vice-versa. Nic Marks created this index. He describes it in the short (1:54) video below if you are so interested. Also, you can read more about HPI here [33].

Optional Viewing

Everybody wants to live a good life, and I presume we want people in the future to live good lives. We created that the happy planet index really to highlight the tension between creating good lives now and good lives in the future.

Because we think people should be happy and the planet should be happy, why don't we create a measure of progress that shows that? And what we do is we say that the ultimate outcome of a nation is how successful is it at creating happy and healthy lives for its citizens? Economic activity tends to be taken as a sign of the sort of strength and power of a nation, and yet all it is, is just economic turnover.

What the happy planet index does is, it takes two things really: it's looking at the well-being of citizens in countries and then is looking at how many resources they use.

It creates what we'll call an efficiency measure: it says how much well-being do you get for your resources? It's like a miles per gallon, bang per buck indicator.

Running horizontally on the graph, ecological footprint is how much pressure we put on the planet. More is bad. Running vertically upwards is a measure called happy life years. It’s like a happiness adjusted life expectancy, and the yellow dot there you see is the global average.

The challenge really is to pull the global average up here. That's what we need to do. And if we're going to do that, we need to pull countries from the bottom, and we need to pull countries from the right of the graph, and then we're starting to create a Happy Planet.

You can download the report, you can check out your own personal HPI score. That’s the first global index of sustainable well-being.

Social Justice

There is no single definition for social justice, but take a moment to think about the definition of social justice from the National Association of Social Workers [34], who provide a good, concise definition:

Social justice is the view that everyone deserves equal economic, political and social rights and opportunities.

Ultimately then, social justice is about equal rights and opportunities, which is a near-universal ideal of democratic and moral societies. Not so bad, right? But let's unpack that definition a little before we move on.

First, it is important to point out that they use the word, everyone. This seemingly innocuous word actually lies at the core of social justice! I'm sure you can think of many historical and contemporary examples of unequal rights being granted to groups of people. Examples abound of discrimination against people of certain ethnicities, races, religious beliefs, sexual orientations, income levels, genders, and more. Social justice requires such characteristics and qualities have no bearing on rights and opportunities. Let's take a look at each of the "types" of opportunities indicated in the definition above.

- Having equal political rights and opportunities refers to everyone having equal ability to participate in all political processes. The most basic aspect of this is the right to vote, but also entails equal opportunity to vote (e.g., by not being subject to voter suppression or intimidation), equal ability to run for office, equal ability to influence political decisions (e.g., by money not being very influential in politics), and more.

- Equal economic rights and opportunities essentially refers to everyone having reasonable access to rights and opportunities that can result in economic security and stability. This includes things such as access to jobs with livable wages, access to good education and training, and fair lending practices.

- Equal social rights and opportunities overlap significantly with economic rights and opportunities. Social rights include things like education, safe neighborhoods, health care, legal protection, access to transportation, access to healthy food, freedom to practice religion, and more.

Please keep in mind that social justice requires equal access to these rights and opportunities. If someone has access to a good education but does not take advantage of it, that is on them. But if they do not have access to it in the first place (e.g., by college being too expensive or public schools in low-income areas being underfunded), that would be considered social injustice. Conceptually, this is straightforward, but practically speaking it can be difficult to determine where injustices occur because the lines between having opportunities and taking advantage of the opportunities is not always clear.

Environmental Justice

Environmental justice is very closely related to social justice. It is the notion that everyone should have equal rights and opportunities to access a reasonably clean environment. Things like clean air, a safe water supply, and natural areas to enjoy are not available to all. In short, environmental "goods" and "bads" are unevenly distributed. The short video below does a great job of illustrating this phenomenon.

Optional Viewing

Where we live in society plays a huge role in the environmental benefits and risks that we're exposed to. And, I'm gonna actually draw in different parts of society by using this line which represents a spectrum of society. On the right hand side, I'm gonna draw part of society that experiences higher poverty and also incorporates the often disadvantaged racial and minority groups. On the left hand side, I'm gonna draw a much wealthier part of society. One of the things that we know is that living areas that experience high poverty and have a lot of racial minorities often have few environmental benefits compared to the wealthier part of society. What do I mean by environmental benefits? I mean green spaces, parks, recreational areas. What does that look like? Well, let me draw it for you, using this triangle. This is supposed to represent environmental benefits. And one of the things we can see is that the wealthier part of society has much higher benefits than the high poverty and racial minority part of society. And as I mentioned, those benefits include things like parks, bike paths, and other green spaces. So one part of society seems to be getting a lot of benefit while another part of society seems to not be getting as much benefit. But what the high poverty and racial minority part of society does get, it does get something, and what it does get, it gets a lot of environmental burden.

So what does that look like? This line is actually supposed to represent increasing burden. So compared to the high income part of society the high poverty and racial minorities get increasing burden. And this includes things like waste facilities, manufacturing and factories, energy production, and transportation facilities such as airports. And one of the things we have to consider is that these are disadvantaged populations, they are really at risk because they're disadvantaged in many ways. They often have few alternatives in terms of where they work and where they live. They may have little awareness of the risks they may face being exposed to various environmental risks or pollutants or chemicals. They may also have other pressing issues, meaning that environmental issues are low on their agenda and let us contrast that to the wealthier population. The wealthier population may very well be more politically powerful, they can also be economically powerful, literally being able to demand that the environmental beneficial facilities are placed close to them, and the burdensome facilities are placed far away. And being able to control things like laws and regulations to benefit them more so than the other communities. And they can also be better represented in environmental groups or lobbying groups. Now this is all of significance when we consider that the high poverty groups and racial minorities may have health problems such as asthma or obesity, because we know conditions like asthma have got strong correlations to environmental issues such as pollutants, particles and ozones, and these are part of the environmental burdens that these populations face. And also when we consider obesity, obesity can be thought of as a lack of access to safe recreational facilities where people can exercise. So a lack of access to environmental benefits, and lack of access to affordable grocery and shopping facilities. The big concept here, that I want to write down is the concept of environmental justice. And what this concept really looks at is that there is a fair distribution of the benefits and burdens, of the environmental benefits and burdens within society, across all groups. And as we can see here, that is clearly not happening at the moment, and much action still needs to be taken.

You may have caught the narrator's definition of environmental justice:

A fair distribution of environmental benefits and burdens across all groups.

This sums it up quite well, though it does leave the door open for some wiggle room in what it specifically means. Take another look at the definition. Do you see anything that might be open to interpretation? How about the word "fair"? This is most definitely open to interpretation, but perhaps that is done on purpose. Similar to the economic aspect of social justice, it is not reasonable to think that everyone will have equal access to all environmental goods and equal exposure to all environmental bads. But what we can strive for is to try to provide equal opportunities to access for as many people as possible.

Final Note on Social and Environmental Justice

You would think that establishing societies that provide equal rights and opportunities to all would not be controversial. The thing about it - this is is widely considered one of the (if not the primary) core values of American society. Yet, social and environmental justice are often some of the most controversial aspects of sustainability. Though there are, unfortunately, many that do not believe that everyone should have equal rights, more often the controversy arises as a result of the application of solutions to social and environmental injustice. There are many reasons for this, but some important ones are as follows:

- By their very nature, fixing social justice issues requires altering the power structure of a given area or society. When women and black Americans were given the right and opportunity to vote in the U.S., it reduced the power of white males. If lobbying activity is restricted, the companies they work for would have less influence, and so on. Those with power tend to try to hold onto it, and because they are already powerful, it can be difficult to stop them.

- There is often a strong ideological resistance to new regulations. Regulation is often posed as solutions to address social and environmental injustice, e.g., by taxing companies and wealthy individuals to subsidize those of lower incomes, taxing companies that pollute or otherwise damage local environments, and so forth.

- The root cause of many of these problems cannot easily be fixed, even with the best-intended policies. For example, urban and rural poverty - both in the U.S. and abroad - is a complex, deep-seated problem that does not have an easy solution. There is no "magic bullet" to fix them. It's difficult to blame businesses for wanting to locate in wealthier areas where people have more money to spend, for example.

- Finally, it is very important to note that providing equal opportunity sometimes requires what some would consider "unequal" treatment. For example, many social and environmental justice organizations provide more resources to low income individuals than those with higher incomes. This can seem unfair to those not eligible for benefits. ("Why won't the government subsidize my housing and childcare?" "Why do I pay more taxes, just because I've made more money through my hard work?")

The goal of those concerned with social/environmental justice is to provide equal opportunity for all people, and there is wide recognition that many people are born at a disadvantage through no fault of their own. In general, social justice advocates err on the side of providing extra assistance and/or helping empower all who might need help, regardless of how they got into their circumstance. We live in a VERY unequal world, and those concerned with social justice want to change that.

Summary and Final Tasks

Summary

By now you should be able to:

- define and provide examples of negative externalities;

- analyze the implications of achieving a steady state economy, and how they relate to ecological footprint;

- identify the pros and cons of energy return on energy invested;

- describe the (in)adequacies of using GDP as a development metric;

- analyze the viability of various development metrics;

- define social and environmental justice;

- identify examples of social and environmental (in)justice.

Reminder - Complete all of the Lesson 2 tasks!

You have reached the end of Lesson 2! Double-check the to-do list on the Lesson 2 Overview page [35] to make sure you have completed all of the activities listed there before you begin Lesson 3.