Lessons

L1: Why spatial data is special

The links below provide an outline of the material for this lesson. Be sure to carefully read through the entire lesson before returning to Canvas to submit your assignments.

Lesson 1 Overview

Spatial data is special and can be problematic. However, as we will see later in this course, there are instances when this can be useful, so understanding how we deal with it is important.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- List four major problems in the statistical analysis of geographic information: autocorrelation, the modifiable areal unit problem, scale dependence, edge effects.

- Identify and discuss the implications of the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem.

Checklist

Lesson 1 is one week in length. (See the Calendar in Canvas for specific due dates.) The following items must be completed by the end of the week. You may find it useful to print this page out first so that you can follow along with the directions.

| Step | Activity | Access/Directions |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Work through Lesson 1 | You are in the Lesson 1 online content now. Be sure to carefully read through the online lesson material. |

| 2 | Reading Assignment | Before we go any further, you need to complete the reading from the course text plus an additional reading from another book by the same author:

|

| 3 | Weekly Assignment | Examine the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem while analyzing voting results |

| 4 | Term Project | Post term-long project topic idea to the project topic discussion forum in Canvas. |

| 5 | Lesson 1 Deliverables |

|

Questions?

Please use the 'Discussion Forum' to ask for clarification on any of these concepts and ideas. Hopefully, some of your classmates will be able to help with answering your questions, and I will also provide further commentary where appropriate.

The Pitfalls of Spatial Data

Required Reading:

Read the course textbook, Chapter 1: pages 1-21.

Also read: Chapter 3, The Modifiable Areal Unit Problem, pages 29-44 in Lloyd, C. D. (2014). Exploring Spatial Scale in Geography. West Sussex, UK: Wiley Blackwell. This text is available electronically through the PSU library catalog.

Spatial Autocorrelation

The source of all the problems with applying conventional statistical methods to spatial data is spatial autocorrelation [3]. This is a big word for a very obvious phenomenon: things that are near each other tend to be more related than things that are far apart. If this were not true, the world would be a very strange and rather scary place. For example, if land elevation were not spatially autocorrelated, huge cliffs would be everywhere. Turning the next corner, we would be as likely to face a 1000-meter cliff (up or down, take your pick!), as a piece of ground just a little higher or a little lower than where we are now. An uncorrelated, or random, landscape would be extremely disorienting.

The problem this creates for statistical analysis is that much of statistical theory is based on samples of independent observations that are not dependent on one another in any way. In geography, once we pick a study area, we are immediately dealing with a set of observations that are interrelated in all sorts of ways (in fact, that's what we are interested in understanding more about).

Having identified the problem, what can we do about it? Depending on how deeply you want to go into it, quite a lot. At the level of this course, we don't go much beyond acknowledging the problem and developing some methods for assessing the degree of autocorrelation (Lesson 4). Having said that, there are some methods that recognize the problem and take advantage of the presence of spatial autocorrelation to improve analysis. These include point pattern analysis (Lesson 3) as well as interpolation and some related methods (Lesson 6) that recognize the problem and even take advantage of the presence of spatial autocorrelation to improve the analysis.

The Ecological Fallacy

The ecological fallacy may seem obvious, but it is routinely ignored. It is always worth keeping in mind that statistical relations are meaningless unless you can explain them. Until you can develop a plausible explanation for a statistical relationship, it is unsafe to assume that it is anything more than a coincidence. Of course, as more and more statistical evidence accumulates, the urgency of finding an explanation increases, so statistics remain useful.

The Pitfalls of Spatial Data, II

In Lesson 1's reading we learned about some of the reasons why spatial data is special, including spatial autocorrelation, spatial dependence, spatial scale, and the ecological fallacy.

This week in our project we will look closely at another pitfall, the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP).

The Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP)

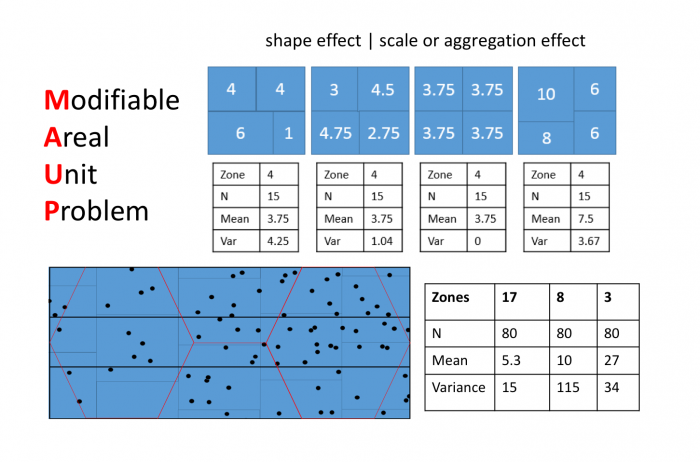

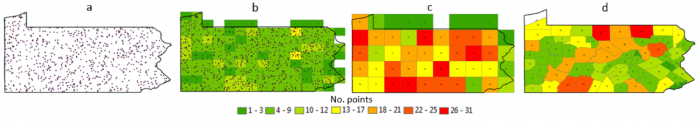

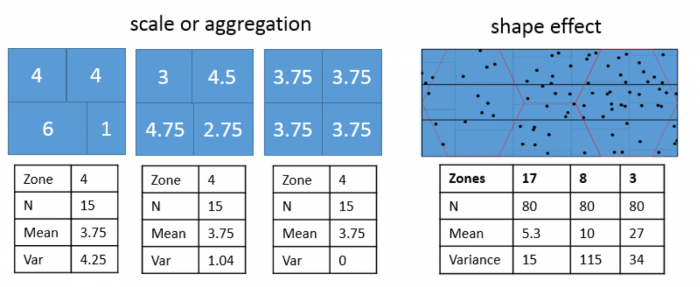

Often, MAUP is considered to consist of two separate effects:

- A shape or zonation effect

- A scale or aggregation effect

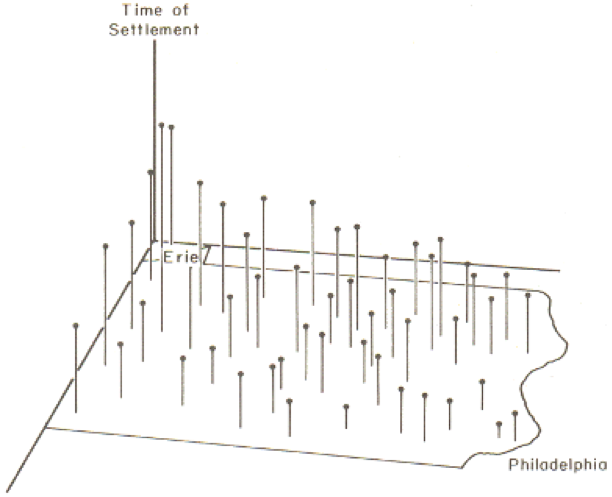

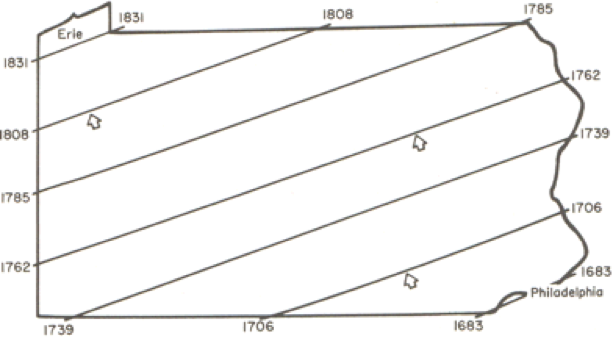

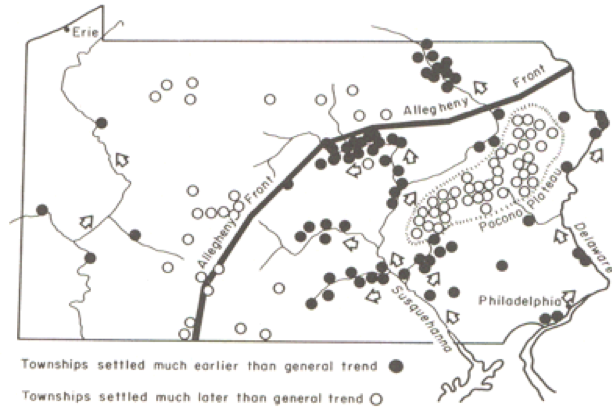

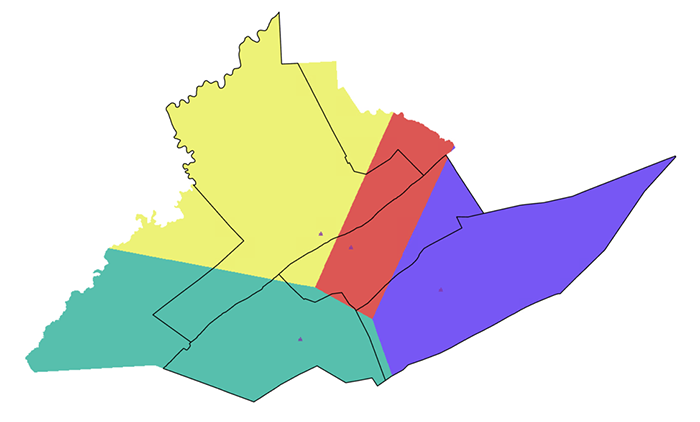

Both effects are evident in the example in Figure 1.2 and further emphasized in Figure 1.3. The shape effect refers to the difference that may be observed in a statistic as a result of different zoning schemes at the same geographic scale. This is the difference between the 'north-south' and 'east-west' schemes. The scale or aggregation effect is observable in the difference between the original data and either of the two aggregation schemes.

Aggregation:

- combines smaller units into bigger units

- affects results!

- variance (Figure 1.3, left) decreases, although the mean stays the same.

MAUP is, if anything, more problematic than spatial autocorrelation. It is worth emphasizing just how serious the MAUP effect can be: in a 1979 paper, Openshaw and Taylor demonstrated by simulation that different aggregation (i.e., zoning) schemes could lead to variation in the apparent correlation between two variables from -1 to +1, in other words, the total range of variation possible in the correlation between two variables.

In practice, very little research has been done on how to cope with MAUP, even though the problem is very real. MAUP is familiar to politicians, who often seek to redistrict areas to their spatial advantage in a practice commonly referred to as "gerrymandering." In the practical work associated with this lesson, you will take a closer look at this issue in the context of redistricting in the United States.

Project 1: Converting and Manipulating Spatial Data

Background

In this week's project, we use an example from American electoral politics to revisit the modifiable areal unit problem (introduced in the reading for Lesson 1) and also as a reintroduction to ArcGIS, in case you've gotten rusty. This lesson's project is based on a real dataset. You will begin using the Spatial Analyst extension and learn to convert data between different spatial types. The ease with which you can do this should convince you that many of the distinctions made between different spatial data types are less important than they may at first appear.

Project Resources

- You will be using ESRI's ArcGIS Pro software (or ArcGIS Desktop 10.X) and the Spatial Analyst and Geostatistical Analyst extensions in this course.

As a registered student in GEOG 586, you can get either:- a free Student-licensed edition of ArcGIS Pro.

- a free Student-licensed edition of ArcGIS Desktop.

Instructions on how to access and download either of these are available here: Downloading Esri Products from Penn State [4].

- The data you need for Project 1 are available in Canvas for download. If you have any difficulty downloading, please contact me.

Geog586_Les1_Project.zip -- A file geodatabase containing the data sets required for the project.

Once you have downloaded the file, double-click on the .zip file to launch 7-Zip or another file compression utility. Follow your software's prompts to decompress the file. You should end up with a folder called TexasRedistricting.gdb, which contains a large number of fairly small items.

Summary of the Minimum Project 1 Deliverables

As you complete certain tasks in Project 1, you will be asked to submit them to your instructor for grading.

The final page of the lesson's project instructions gives a description of the form the weekly project reports should take and content that we expect to see [5] in these reports. In this course you will not only practice conducting geographical analysis but also learn about how to communicate analytical results.

To give you an idea of the work that will be required for this project, here is a summary of the minimum items you will create for Project 1. You should also get involved in discussions on the course Discussion Forum about which approach of the three described in this lesson (polygon to point, KDE, or uniform distribution) is most appropriate, before choosing one.

- Create a map of the RepMaj attribute for districts108_2002 for your write-up, along with a brief commentary on what it shows: Are Republican districts more rural or more urban? What other patterns do you observe, if any?

- Comment on the new Districting plan adopted by the Texas Senate in October 2004. What would you expect it to do to the balance of the electoral outcome? Can you tell, just by examining this map? Put your comments in your write-up.

- Create a map of the 'predicted' electoral outcome for the new districts similar to the original map for the 2002 election and insert it into your write-up. Feel free to provide additional commentary on this topic.

Questions?

Please use the 'Week 1 lesson discussion' forum to ask for clarification on any of these concepts and ideas. Hopefully, some of your classmates will be able to help with answering your questions, and I will also provide further commentary there, where appropriate.

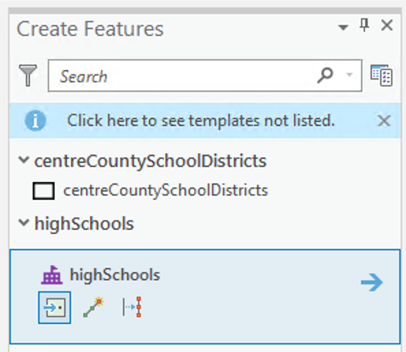

Project 1: Getting Started

- Open ArcGIS Pro and create a new project with the Map template. If you haven't used ArcGIS Pro in another course or at work, or if it has been a while since you've last used it and you need a refresher, you might consider walking through one or two of the QuickStart tutorials [6] on the Esri website to learn about how it is organized a bit differently to ArcMap. One of the nice things about ArcGIS Pro is that it will automatically save your analysis results to the project geodatabase, so you no longer have to set path names.

- Open the Catalog Pane and use it to add the feature classes in TexasRedistricting.gdb file geodatabase to your project. You will first need to add a connection to the geodatabase so that you can see the files (as you would have in ArcMap). To begin with, you only need to look at districts108_2002. This shows the 32 Congressional districts in Texas in which the Federal elections were held in November 2002. One attribute in this file is RepMaj, an integer value indicating the winning margin for the Republican candidate in each district (a negative value if the Republican candidate lost).

- Create a map of the RepMaj attribute for districts108_2002. For best results, you should use a diverging color scheme with two color hues, with pale colors showing results near 0, and deeper colors indicating a larger majority for one party or the other (red for Republicans and blue for Democrats is conventional).

- Make sure to save the project file periodically so that you don't lose work if ArcGIS crashes.

Deliverable

Put this map in your write-up, along with a brief commentary (a few sentences or short paragraph will suffice) on what it shows: Are Republican districts more rural or more urban? What other patterns do you observe, if any?

- Next, look at the tx_voting108 data. This records votes cast for the Republican and Democratic candidates in county-based subdivisions of the districts.

Note:

Note that counties and congressional districts are not a precise fit inside one another, so many of the units in tx_voting108data are parts of counties that were subdivided among two or more districts.

- Also examine the new Districting plan adopted by the Texas Senate in October 2004. This is shown in newDistricts2003. You may find it helpful to put this layer on top and set the fill to 'no color' so that the outlines of these districts are visible over the top of your previous map of the electoral outcome in the 108th Congressional Districts.

Deliverable

Comment on the redistricting plan. What would you expect it to do to the balance of the electoral outcome? Can you tell, just by examining this map? Put your comments in your write-up.

Project 1: Estimating results for the new Congressional Districts

In the next few pages, the steps required to estimate possible outcomes of the 2004 election based on the new districting plan by three different methods (Polygon to point, KDE, and uniform distribution) are described, along with an explanation of what each method will do.

After reviewing these methods, you should get involved in the discussions on the course Discussion Forum for this week's project, and then choose one of these methods and proceed to complete the project by producing a map of the estimated 2004 election result. Completion of the project also requires you to comment on your choice of method.

Before using any of the methods, you should check that the Spatial Analyst extension is enabled. You can do this in Project - Licensing. You should see that it says 'Yes' in the Licensed column in the Esri Extensions table.

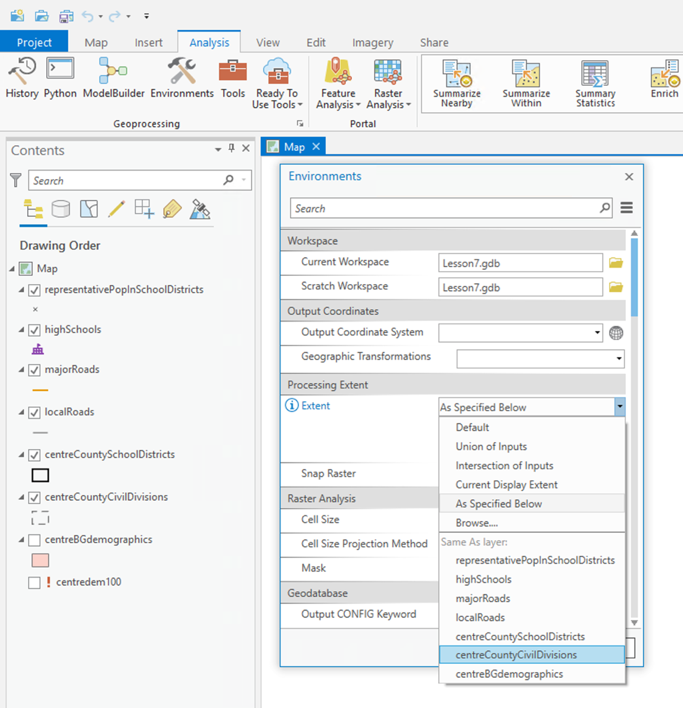

Once Spatial Analyst is enabled, you should also select the following settings from the Analysis - Environments... menu:

- Under Processing Extent, select 'Same as Layer "tx_voting108"' as the 'Extent'. This ensures that the analysis is carried out to the state boundary.

- Under Raster Analysis, select tx_voting108 as the 'Mask', and for 'Cell size', type a value of 1000 into the box. This will ensure that output raster layers have a cell resolution of 1 kilometer. You may optionally decide that this resolution is rather high and change it to something larger [using too high a resolution can be a problem if you are using the VPN to access ArcGIS Pro, so keep this in mind].

With these settings completed, you are ready to try the alternative methods for generating voter population surfaces.

Project 1: Density Surface Options

Option 1: Points at Polygon Centroids

The first option is to make a set of points, one for each polygon in our 2002 voting data, and to use these to represent the distribution of the vote that might be expected in 2004. This approach assumes that it is close enough to assign all the voters in each polygon to a single point in the middle of that polygon.

This is a two-step process, creating a point layer, and converting the point layer to a raster.

To make the point layer:

- Open the Geoprocessing pane from Analysis-Tools. Then search for the Feature to Point tool with the search bar and launch it. Select tx_voting108 as the 'Input Features' and specify a name for the point layer to be produced. You may also optionally choose to force the points to lie inside the polygons.

NOTE: this is a step that requires an Advanced level license. Your student license should be an Advanced level license.

HOWEVER... because this is Lesson 1, we have provided the results of this step (with the 'force inside' option not selected), in the layer tx_voting108_centers layer.

By whatever means you arrive at a point layer, make sure you understand what is going on here. In particular, check to see if all polygons have an associated center point. Are all the 'centers' inside their associated polygons? (If not, why not?)

Once you have the point layer, you can make raster layers (one for Republican voters, and one for Democratic voters) as follows:

- Search for and launch the Point to Raster tool.

- Select the centroids layer you just made as the Input Features and either REP or DEM as the 'Value field' (you need to make one surface for each attribute).

- Also specify a name for the new raster surface to be created (reps_point or dems_point as appropriate).

- Use 'SUM' as the 'Cell assignment type' (why?).

You will get a raster layer with No Data values in most places, and higher values at each location where there was a point in the centroids layer.

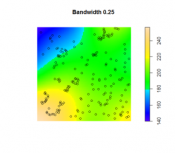

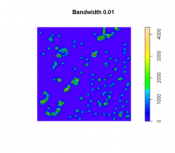

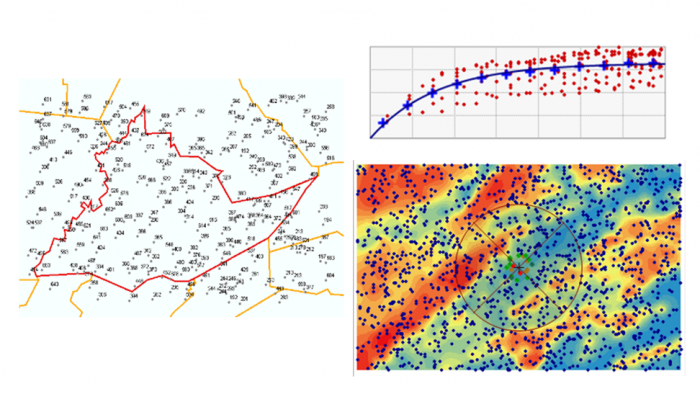

Option 2: Density Estimation from Points

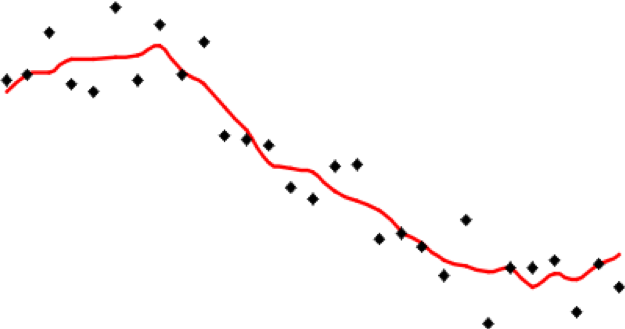

The second option is to use kernel density estimation (which we will look at in more detail in Lesson Three) to create smooth surfaces representing the voter distribution across space. This method requires you to choose a radius that specifies how much smoothing is applied to the density surface that is produced.

The steps required are as follows:

- Search for and launch the Kernel Density tool

- Set 'Input data' to the point centers layer (as made in the previous method). For the 'Population field' select REP or DEM (you will be doing both anyway). Set the 'Search radius' to 20,000 [or another value you feel is appropriate for modelling voter distribution], and 'Area units' to 'Square Kilometers'. You should also specify a name to save the output to (I suggest reps_kde, or dems_kde, as appropriate). Then run the tool.

The search radius value here specifies how far to 'spread' the point data to obtain a smoothed surface. The higher the value, the smoother the density surface that is produced.

If you encounter problems, post a message to the boards, and also check that the map projection units you are using are meters (the easiest way to check this is to look at the coordinate positions reported at the bottom of the window as you move the cursor around the map view).

When processing is done, ArcGIS Pro adds a new layer to the map, which is a field of density estimates for voters of the requested type. You should repeat steps 1 and 2 to get a second field layer for the other political party, making sure that you calculate both fields with the same parameters set in the Kernel Density tool.

NOTE: If you have changed the Analysis Environment Cell Size setting from the suggested 1000 meters, then the density values you get are correct, but when it comes to summing them (in a couple more steps' time), they will not produce correct estimates of the total number of votes cast for each party. This is because the density values are per sq. km, but there is not one density estimate for every sq. km. For example, if you set the resolution to 5000 meters, then there will be one density estimate for every 25 sq. kms. To correct for this, you need to use the raster calculator to multiply the density surface by an appropriate correction factor: in this case, you would multiply all the estimates by 25.

NOTE 2: If you are running ArcGIS Pro 2.8 or later, there has been a change to how the KDE tool works. To produce the expected result, you will need to change the processing extent in the Environments tab to either the same as the 'tx_voting108' layer or to the 'union of inputs'. Otherwise, you'll see a result that appears to include only North Texas.

Option 3: Assumed even population distributions

The third option is to assume that voters are evenly distributed across the areas in which they have been counted. We can build a surface under that assumption and base the final estimated votes in the new districts based on that. This method takes a couple of steps and creates two intermediate raster layers using the Spatial Analyst extension on the way to the final estimate.

A number of steps are required:

- Search for and launch the Polygon to Raster tool and use it to make new raster layers from the OBJECTID, REP and DEM fields of the tx_voting108 layer. You will need to run the tool three different times, to make three different layers. The default cell size should be 1000 meters. You should specify a sensible (and memorable) name for each raster layer you create (reps, dems, ids are what I used).

- For the raster layer made from the OBJECTID field, you need to count the size of each area, in raster cells. Search for and launch the Lookup tool from the Spatial Analyst toolbox. Choose your ids raster as the 'input raster', Count as the 'lookup field', and name your output layer ids_count. This will produce a new raster that stores the number of pixels in each voting district. Because you set the cell size to 1000 meters, this is also effectively an area in square kilometers.

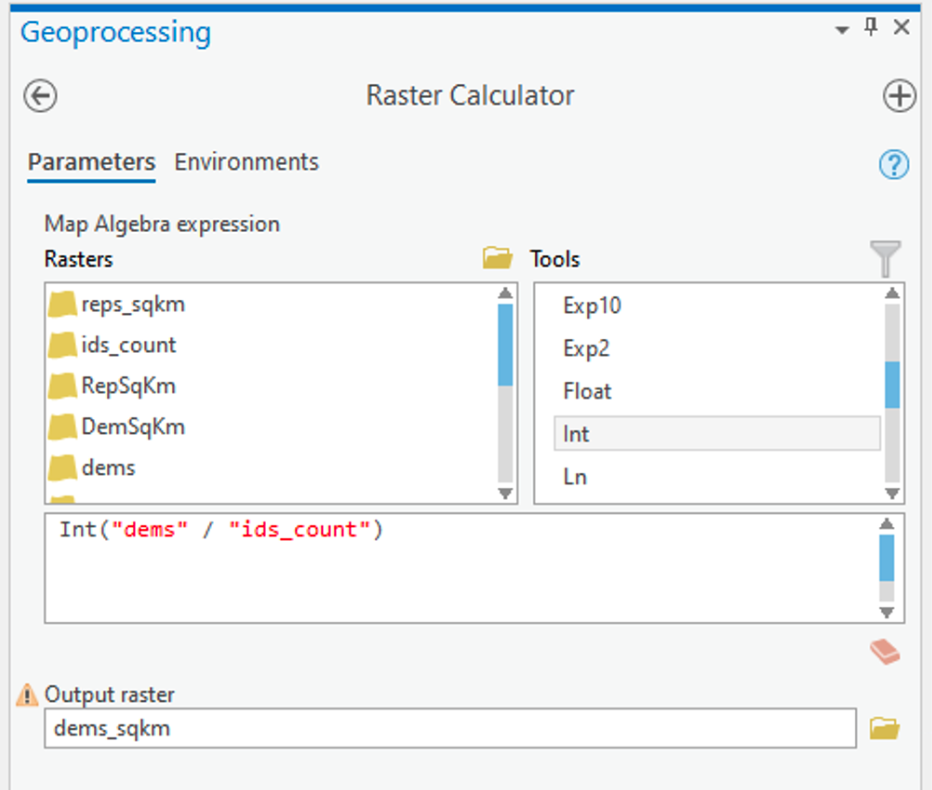

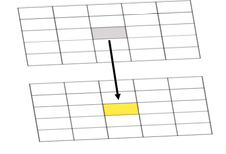

- Now, search for and launch the Raster Calculator tool. Then, for each party, use the Raster Calculator to calculate the number of Republican and Democratic Party voters per raster cell (i.e., per square kilometer) as shown in Figure 1.4. Notice that we used the int function to make sure that we have integers because votes only exist in integer quantities -- there are no partial votes! Make sure you build the expression by clicking on items rather than typing. This will make it less likely that you get a syntax error.

Figure 1.4: Raster CalculatorClick for a text description of the Raster Calculator Example image.The raster calculator expression should be the name of the democrat raster layer divided by the result of the lookup tool. Notice that we used the int function to make sure that we have integers because votes only exist in integer quantities – there are no partial votes! The output parameter should set the name of the output to something informative.Credit: Griffin

Figure 1.4: Raster CalculatorClick for a text description of the Raster Calculator Example image.The raster calculator expression should be the name of the democrat raster layer divided by the result of the lookup tool. Notice that we used the int function to make sure that we have integers because votes only exist in integer quantities – there are no partial votes! The output parameter should set the name of the output to something informative.Credit: GriffinArcGIS Pro will think about things for a while and should eventually produce a new layer (in this case called dems_sqkm). This layer contains in each cell an estimate of the number of voters of the specified party in that cell.

Project 1: Creating an Estimated Republican Majority Surface

Whichever approach you have chosen to make voter population surfaces, it is the difference between the votes for each party that will determine the estimated election results; so, at this point, it is necessary to combine the two estimated surfaces in a 'map calculation'.

- Use the Raster Calculator to specify an equation subtracting the estimated Democratic Party voter density from the estimated Republican Party voter density, and run the tool. Call your resulting layer RepMaj plus a suffix that indicates which density surface method you derived the layer from.

You should get an output surface that is positive in some areas (Republican majority) and negative in others (Democratic majority).

NOTE: If you are interested in comparing the results of the three methods, you need to calculate the difference between the votes for each party described above, and the step described on the next page for each of the methods (i.e., three times). The comparison between the three methods is optional.

Project 1: Aggregating Density Surface Data to Areas

Whichever approach you chose to make the Republican majority surface, the final step is to sum the estimated majorities that fall inside each new Congressional District in the newDistricts2003 layer to get a predicted outcome for the 2004 elections:

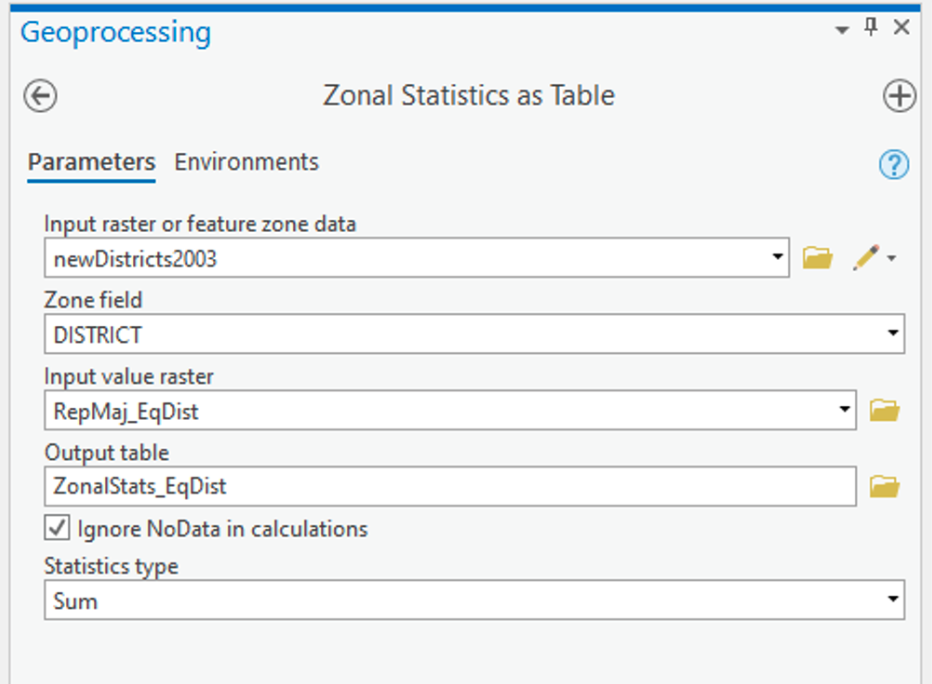

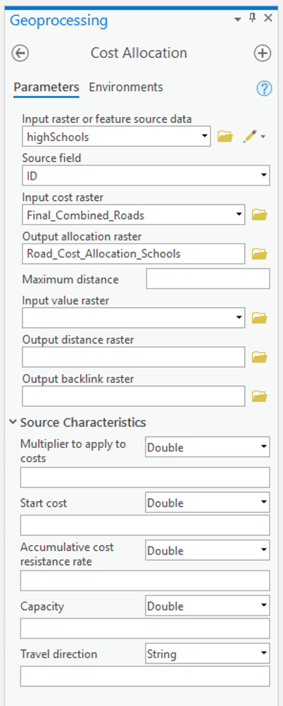

- Search for and launch the Zonal Statistics as Table tool. The settings in Figure 1.5 should work (with any necessary changes to layer names):

Figure 1.5: Zonal Statistics as TableClick for a text description of the Zonal Statistics as Table Example image.The input feature zone tool parameter should be set to newDistricts2003. For the zone field parameter, choose DISTRICT. The input value raster is the layer you created in the previous step. The output parameter should give the result of this tool a sensible name. Finally, the statistics type should be set to SUM.Credit: Griffin

Figure 1.5: Zonal Statistics as TableClick for a text description of the Zonal Statistics as Table Example image.The input feature zone tool parameter should be set to newDistricts2003. For the zone field parameter, choose DISTRICT. The input value raster is the layer you created in the previous step. The output parameter should give the result of this tool a sensible name. Finally, the statistics type should be set to SUM.Credit: GriffinThis will make a table of values, one for each new district, which is the SUM of the Republican majority surface values inside that district.

Once you've done this summation, you should be able to join the table produced to the newDistricts2003 layer via the DISTRICT field, so that there is now an estimated Republican majority for each of the new districts. Using this new attribute, you can make a map of the 'predicted' electoral outcome for the new districts similar to the original map for the 2002 election, but based on the estimated Republican majority results.

Deliverable

You should insert this new map into your write-up. Feel free to provide additional commentary on this topic. Points to consider include:

- How does the overall outcome differ from the 2002 results?

- How many congressional races did the Republicans win in 2002?

- How many might you expect them to win in 2004 with the new congressional districts, based on your analysis?

- Is there anything about the spatial characteristics of the new districts that might lead you to think they were constructed with electoral advantage in mind, rather than fairness?

- What sort of spatial characteristics might be used to spot egregious examples of gerrymandering?

- Why did you choose the method you did to make the estimates?

- What problems do you see in the method we have used to estimate the next round of elections? (This includes weaknesses in the basic assumptions, as well as more technical matters.)

Project 1: Finishing up

Here is a summary of the minimal deliverables for Project 1. Note that this summary does not supersede elements requested in the main text of this project (refer back to those for full details). Also, you should include discussions of issues important to the lesson material in your write-up, even if they are not explicitly mentioned here.

- A map of the RepMaj attribute for districts108_2002, along with a brief commentary on what it shows.

- A short commentary on the new Districting plan adopted by the Texas Senate in October 2004.

- A map of the 'predicted' electoral outcome for the new districts in the newDistricts2003 layer similar to the original map for the 2002 election and an accompanying commentary on how you made this map, problems with the method, and any other issues you wish to mention

Form and structure of weekly project reports

Your report should present a coherent narrative about your analysis. You should structure your submission as a report, rather than as a bullet list of answers to questions.

Part of the learning in this course relates to how to write up the results of a statistical analysis, and the weekly project reports are an opportunity to do this and to get feedback before you have to report on your term-long projects.

In your report, you should include:

- An introduction and conclusion section that sets the context for (i.e., describes the aims, goals and objectives) and summarizes the major takeaways of the analysis, respectively.

- Use section headers to help you organize your ideas and to assist the reader to better understand the framework of your analysis.

- Make sure that for every figure and/or table you include in your write-up, you use figure numbers and captions as well as table numbers and headers. Figure and caption numbers should be unique and sequential. Table numbers and captions go above the table, while figure numbers and captions go below the figure.

- Reference each figure and/or table individually in the text of your report (e.g., Figure 1 or Table 2). Doing so is reflective of professional writing practices.

- Make sure that all parts of each figure are legible and that the information presented in tables is well-organized.

- Cite back to the lesson material and text book for ideas that link course concepts to your analysis. This helps to present an intellectual foundation for your analysis and provides evidence that you understand how the theory of the lesson applies to the practice of spatial analysis.

- While there is a detailed rubric for each lesson (shown in the grade book), I will be particularly checking for evidence of careful examination of the dataset and any of limitations of the data you observe through your exploratory analysis.

Please put one of the following into the assignment dropbox for this lesson:

- A PDF of your write-up, -or-

- An MS-Word compatible version.

Make sure you have completed each item!

That's it for Project 1!

Term Project Overview and Weekly Deliverables

Throughout this course, a major activity is a personal GIS project that you will develop and research on your own (with some input from everyone else taking the course). To ensure that you make regular progress toward completion of the term project, I will assign project activities for you to complete each week.

The topic of the project is completely up to you, but you will have to get the topic approved by me. Pick a topic of interest, and use the different methods applied during this class to better understand the topic.

This week, the project activity is to become familiar with the weekly term project activities and to think about possible topics and post an idea you have in mind. Each week, the project activity requirements for that week will be spelled out in more detail on a page labeled 'Term Project', located in the regular course menu.

Term Project: Breakdown of Week by Week Activities

The breakdown of activities and points are as follows:

- Week 1: 1 point for posting topic ideas

- Week 2: 2 points for submission of a project proposal

- Week 4: 3 points for on-time submission of a satisfactory revised project proposal

- Week 5: 3 points for feedback to your colleagues on their project proposals

- Week 6: 6 points for the final project proposal

- Week 9: 12 points for quality of the project and the report

- Week 10: 3 points for your involvement in discussions of the final projects

Below is an outline of the weekly project activities for the term-long projects. You should refer back to this page periodically as a handy guide to the project 'milestones'.

| Week | Detailed description of weekly activity on term project |

|---|---|

| 1 | Read this overview! Identify and briefly describe a possible project topic (or topics). Post this information to the 'Term Project: Project Idea' discussion forum as a new message. This posting should include a paragraph of no more than 1 page max!, 250 words max!, single spaced, and 11pt or 12pt sized font. |

| 2 | Submit a more detailed project proposal (2 pages max!, 600 words max!, single spaced, and 11pt or 12pt sized font) to the 'Term Project: Preliminary Proposal' discussion forum. This week, you should research your topic a bit more and start to obtain the data you will need for your project. Do not underestimate the amount of time you will need to devote to formatting and manipulating your data. The proposal must identify at least two (preferably more) data sources. Inspect your data sources carefully. It's important to get started on finding and examining your data early. You do not want to find out in Week 8 that your dataset is not viable or will take you two weeks just to format your data for use in the software! Over the next few weeks, you will be further developing your proposal, which will be reviewed by other students and by me, and revised to a more complete form due in Week 6. |

| 3 | This is a busy week, so no term project activity is due. Start getting your interactive peer review meeting date and time organized with your group. |

| 4 | Refine your project proposal and post it to the 'Term Project: Revised Proposal' discussion forum for peer review in Week 5. (2 pages max!, 800 words max!, single spaced, and 11pt or 12pt sized font) |

| 5 | Interactive peer review of term project proposals. You will meet with your group and provide interactive feedback. These reviews are intended to help you further refine your project idea and plans. |

| 6 | A final project proposal is due this week. This will commit you to some targets in your project and will be used as a basis for assessment of how well you have done. The final proposal should be submitted through the 'Term Project: Final Project Proposal' dropbox. (3 pages max!, 1,000 words max!, single spaced, and 11pt or 12pt sized font) |

| 7 | You should aim to make steady progress on the project this week. |

| 8 | You should aim to make steady progress on the project this week. |

| 9 | This week, you should complete your project work and post it as a PDF attachment on the 'Term Project: Final Discussion' discussion forum and let the class know that you are finished. The report should be suitable for anyone involved with the course to read and understand. Note that there are no other course activities at all this week, to give you plenty of time to work on completion of the project. You should also submit the final term project to the 'Term Project: Final Project Submission' dropbox. (20 pages max! inclusive of all required elements, approximately 10,000 words, single spaced, and 11pt or 12pt sized font) |

| 10 | Finally, the whole class, including the instructor, will use the posted project reports as a basis for reviewing what we have all learned (hopefully!) from the course. Contributions to discussions of one another's projects will be evaluated, as well as the projects themselves. Think of this as a virtual version of an in-class presentation of your project with an opportunity for members of the class (and the instructor) to ask questions, make suggestions, share experiences, review ideas, and so on. |

Term Project (Week 1) - Identifying a Project Topic

In addition to the weekly project, it is also time to start to think about your term project.

- Review the project outline and become familiar with what is required each week. Timely submission of an appropriate topic suggestion is important at this stage since you will need to provide the entire class a project proposal that will be peer reviewed during Lesson 5.

- This week, you need to provide a minimal description of the project that is identifying a topic and its geographical scope. By minimal, I mean a single paragraph that includes no more than 250 words max!, single spaced, and 11pt or 12pt sized font.

- Timely submission of your preliminary project topic.

Deliverable: Post your topic ideas to the 'Term Project: Project Topic' Discussion Forum. One new topic for each student, please! Even at this early stage, if you have constructive suggestions to make, then by all means make them by posting comments in reply to their topic.

Questions?Please use the General Issuesdiscussion forum to ask any questions now or at any point during this project.

Term Project (Week 2) - Writing a Preliminary Project Proposal

Submit a brief project proposal (2 pages max!, 600 words max!, single spaced, and 11pt or 12pt sized font) to the 'Term Project: Preliminary Proposal' discussion forum. This week, you should start to obtain the data you will need for your project. The proposal must identify at least two (preferably more) likely data sources for the project work, since this will be critical to success in the final project. Inspect your data sources carefully. It's important to get started on this early. You do not want to find out in Week 8 that your dataset is not viable! Over the next few weeks, you will be refining your proposal. During Week 5, you will receive feedback from other students. This will help you revise your final proposal which will be due in Week 6.

This week, you must organize your thinking about the term project by developing your topic/scope from last week into a short proposal.

Your proposal should include the following section headers and content for each section:

Background:

-

some background on the topic particularly, why it is interesting or a worthwhile research pursuit;

-

research question(s). What, specifically, do you hope to find out?

Methodology:

-

Data: list and discuss the data required to answer the question(s). Be sure to clearly explain the role each dataset will play.

- Data Sources: Be sure to list where you will (or have) obtain the required data. This may be public websites or perhaps data that you have access to through work or personal contacts.

- Obtain and explore the data: attributes, resolutions, scale.

- Is the data useful or are there limitations?

- Will you need to clean and organize the data in order to use it?

- Obtain and explore the data: attributes, resolutions, scale.

- Data Sources: Be sure to list where you will (or have) obtain the required data. This may be public websites or perhaps data that you have access to through work or personal contacts.

- Analysis: what you will do with the data, in general terms

-

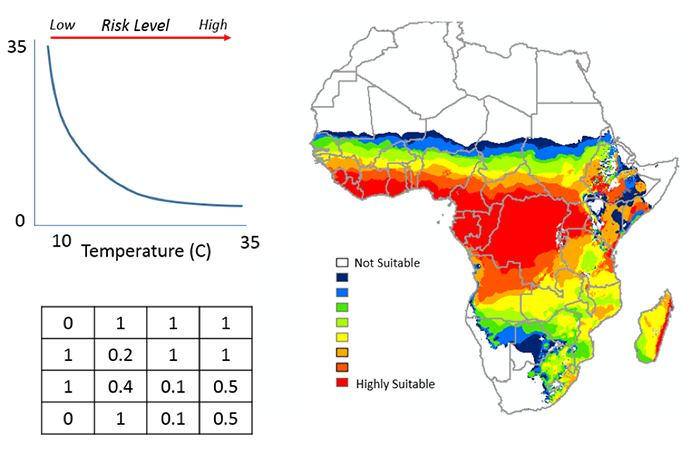

Analysis Methods: What sort of statistical analysis and spatial analysis do you intend to carry out? I realize, at this point, that you may feel that your knowledge is too limited for this. Review Figure 1.2 and skim through the lessons to identify the methods you will be using. If you don't know the technical names for the types of analysis you would like to do, then at least try to describe the types of things you would like to be able to say after finishing the analysis (e.g., one distribution is more clustered than another). This will give me and other students a firmer basis for making constructive suggestions about the options available to you. Also, look through the course topics for ideas.

-

Expected Results:

-

what sort of maps or outputs you will create

References:

-

references to papers you may have cited in the background or methods section. Include URLs to data sources here (if you didn't include the URLs in the Data section.

The proposal does not have to be detailed at this stage. Your proposal should be no longer than 2 pages max!, 600 words max!, single spaced, and 11pt or 12pt sized font. Make sure that your proposal covers all the above points, so that I (Lesson 3 & 4) and others (Lesson 5 – peer review) evaluating the proposal can make constructive suggestions about additions, changes, other sources of data, and so on.

Additional writing and formatting guidelines are provided in the document (TermProjectGuidelines.pdf) in 'Term Project Overview' in Canvas.

Term Project - (Week 3)

No set deliverable this week. Read through other proposals and make comments. Continue to refine your project proposal.

Project Proposal: I will be providing each of you with feedback this week on the Preliminary Project Proposals you submitted last week (Week 2).

Peer-review Groups: I will be assigning you groups this week so that you have plenty of time to set up a meeting time during Week 5.

Revising and finalizing your project proposal. Over the next few weeks, you will be refining and extending your term project proposal and receiving feedback from me and your peers. To make this task less daunting and more manageable, we have broken down the process into a series of steps that allows you to evaluate new methods and their applicability to your project as well as receive feedback. Below is a quick overview of the steps each week.

- Week 3 - You will be assigned a peer review group and receive feedback from the instructor on your preliminary proposal. This week, make arrangements for your group's meeting in Week 5.

- Week 4 - Post your project proposal to the discussion forum as text and also attach the Word document and/or send it to your group. You should meet with your group during Week 5 for 1 hour at a mutually agreed upon time. Once you have set a date and time, send the instructor the information with the Zoom link.

- Week 5 - Meet via Zoom for 1 hour. See the instructions below. Make a post to the peer review discussion board about what feedback you found valuable.

- Week 6 - Further refine your project proposal and submit it to the Final Proposal dropbox.

Term Project (Week 4) - Revising and Submitting a Project Proposal/h3>

Refine your project proposal and post the proposal to the 'Term Project: Peer-Review' discussion forum so that your peer review group can access the proposal.

Your revised proposal should take into account the feedback provided by the instructor in Week 3. Keep the revised proposal to be no more than 2 pages max!, 800 words max!, single spaced, and 11pt or 12pt sized font.

Deliverable: Post your project proposal to the 'Term Project: Revised Proposal' discussion forum and share it with your group.

Term Project (Week 5) - Interactive Peer-Review Process

This week, you will be meeting with your group to discuss your proposed project idea.

You should consider the following aspects:

- Are the goals reasonable and achievable? It is a common mistake to aim too high and attempt to do too much. Suggest possible amendments to the proposals' aims that might make them more achievable in the time frame.

- Are the data adequate for the task proposed? Do you foresee problems in obtaining or organizing the data? Suggest how these problems could be avoided.

- Are the proposed analysis methods appropriate? Suggest alternative methods or enhancements to the proposed methods that would also help.

- Provide any additional input that you feel is appropriate. This could include suggestions for additional outputs (e.g., maps) not specifically mentioned by the author, or suggestions as to further data sources, relevant things to read, relevant other examples to look at, and so on.

Remember... you will be receiving reviews of your own proposal from the other students in the group, so you should include the types of useful feedback that you would like to see in those commentaries. Criticism is fine, provided that it includes constructive inputs and suggestions. If something is wrong, how can it be fixed?

Week 5: Term Project - Interactive Peer Review Meeting and Discussion Post Instructions

Now, you will complete peer reviews. You will be reviewing the other group members' proposals for this assignment. Your instructor will divide the class into groups. The peer reviews will take place using Zoom. You should have arranged the time of the meeting with your group in Week 3 or 4.

- You will arrange to meet with your group for 1 hour using Zoom [7] to interactively discuss your term project. The hour that you meet should be mutually agreed upon by everyone in the group. One team member should agree to be "host."

- Once you have set a date and time, the session "host" should sign in to psu.zoom.us to schedule the meeting; see instructions in below and circulate the "invitation" details to the other group members.

- Send the instructor the meeting details (day and time). The instructor will join the meeting if schedules align. If the instructor can not join the meeting, then record the meeting, then send the instructor a link to the recording for a later viewing.

- Each student has 15 minutes to discuss their project. During this time, each student will describe their project for about 5 minutes and then receive feedback, answer questions, and provide clarifications for the remainder of their 15-minute period.

- Remember to take notes during your question and answer session so that you can incorporate the feedback you receive into your final proposal.

- Once the peer review session is finished, to make your post, click Reply in the Interactive Peer Review discussion forum.

- Click Attach, and select the original term project outline that you uploaded last week (i.e., your revised proposal) and attach it to your discussion post.

- Post 1 sentence to the discussion for each "peer" in your group that indicates the most useful question, comment, or suggestions you received from each of your Peer Review group members (thus 2 or 3 sentences depending on Peer Review group size) and a second sentence that describes how you are thinking about responding to that feedback.

Zoom: As a PSU student, you should have access to Zoom [7]. Once you have been assigned a group, work with your group to set up a mutually agreed upon date and time to meet via Zoom. One team member should agree to be "host". If you have not used Zoom yet, then use the following instructions to set up a meeting [8].

Deliverable: Post a summary of the comments and feedback you received from others about your term-long project in your group to the 'Term Project: Peer Review' discussion forum. Your peer review comments are due by the end of week 5.

Term Project (Week 6) - Finalizing Your Project Proposal

Based on the feedback that you received from other students and from the instructor, revise your project proposal and submit a final version this week. Note that you may lose points if your proposal suggests that you haven't been developing your thinking about your project.

In your final proposal, you should respond to as many of the comments made by your reviewers as possible. However, it is OK to stick to your guns! You don't have to adjust every aspect of the proposal to accommodate reviewer concerns, but you should consider every point seriously, not just ignore them.

Your final proposal should be between 600 and 800 words in length (3 pages max!, 1,000 words max!, single spaced, and 11pt or 12pt sized font). The maximum number of words you can use is 800. You will lose points if your word count exceeds 800. Make sure to include the same items as before:

- Topic and scope

- Aims

- Dataset(s)

- Data sources

- Intended analysis and outputs -- This is a little different from before. It should list some specific outputs (ideally several specific items) that can be used to judge how well you have done in attaining your stated aims. Note that failing to produce one of the stated outputs will not result in an automatic loss of points, but you will be expected to comment on why you were unable to achieve everything you set out to do (even if that means simply admitting that some other aspect took longer than anticipated, so you didn't get to it).

Additional writing and formatting guidelines are provided in the document (TermProjectGuidelines.pdf) in 'Term Project Overview' in Canvas.

Deliverable: Post your final project proposal to the Term Project: Final Proposal dropbox.

Term Project (Week 7) - Continue Working on Your Final Project Report

There is no specific deliverable required this week, but you really should be aiming to make some progress on your project this week!

Term Project (Week 8) - Continue Working on Your Final Project Report

There is no specific deliverable required this week, but you really should be aiming to make some progress on your project this week!

Term Project (Week 9) - Submitting Your Final Project Report

Project Overview

Your report should describe your progress on the project with respect to the objectives you set for yourself in the final version of your proposal. The final paper should be no more than 20 pages max! inclusive of all required elements specified in the list below, approximately 10,000 words, single spaced, and 11pt or 12pt sized font. As a reminder, the overall sequence and organization of the report should adhere to the following section headers and their content:

-

Paper Title, Name, and Abstract -

-

This information can be placed on a separate page and does not count toward the 20 page maximum.

-

Make sure your title is descriptive of your research, including reference to the general data being used, geographic location, and time interval.

-

Don’t forget to include your name!

-

The abstract should be the revised version of your proposal (and any last-minute additions or corrections based on the results of your analysis). The abstract should be no longer than 300 words.

-

-

Introduction - one or two paragraphs introducing the overall topic and scope, with some discussion of why the issues you are researching are worth exploring.

-

Previous Research - provide some context on others who have looked at this same problem and report on their conclusions that helped you intellectually frame your research.

-

Methodology

-

Data - describe the data sources, any data preparation/formatting that you performed, and any issues/limitations with the data that you encountered.

-

Methods - discuss in detail the statistical methods you used, and the steps performed to carry out any statistical test. Make sure to specify what data was used for each test.

-

-

Results - individually discuss the results with respect to each research objective. Be sure to reflect back on your intended research objectives, linking the results of your analysis to whether or not those objectives were met. This discussion should include any maps, table, charts, and relevant interpretations of the evidence presented by each.

-

Reflection - reflect on how things went. What went well? What didn't work out as you had hoped? How would you do things differently if you were doing it again? What extensions of this work would be useful, time and space permitting?

-

References - include a listing of all sources cited in your paper (this page does not count toward the 20 page maximum).

Other Formatting Issues

- Use a serif type face (like Times New Roman), 1.5 line spacing, with 11pt or 12pt sized font.

- Include any graphics and maps that provide supporting evidence that contributes to your discussion. The graphics and maps should be well designed and individually numbered.

- Tables that provide summaries of relevant data should also be included that are individually numbered (e.g., Table 1) and logically arranged.

- For each graphic, map, or image make sure to appropriately reference them from your discussion (e.g., Figure 1) so that the reader can make a connection between your discussion points and each included figure.

Deliverables

- Post a message announcing that your project is 'open for viewing' to the Term Project: Final Discussion discussion forum. You can upload your project report directly to the discussion forum or provide a URL to a website (e.g., Google Docs) where the project report can be found by others in the class!

- At the same time, put a copy of the completed project in the Term Project: Final Project Writeup dropbox.

-

Next week, the whole class will be involved in a peer-review where you will discuss each other's work. You will be reviewing the members of your group from the initial peer-review session in week 5. It is important that you meet this deadline to give everyone a clear opportunity to look at what you have achieved.

Term Project (Week 10) - Submitting Your Final Project Report

Think of this as a virtual version of an in-class presentation of your project with an opportunity for members of the class (and the instructor) to reflect on each other's work.

In order to earn points for this deliverable, you should read through the term papers of those who were in your peer-review zoom session during week 5. Then, post your comments on the papers written by the members of your peer review session in the discussion forum. Here are a few things to consider as you review your group member's write-ups.

- think about the organization of the paper (does the paper flow from an introduction, spatial analysis, and conclusion?)

- what is the research question(s) and it is clearly stated?

- what does the literature review say about the research question?

- what evidence does the analysis provide (is there a spatial component to the evidence)?

- do the results answer the research question(s)?

- is there a conclusion and did you learn anything from the analysis?

These comments can include, but are not limited to, feedback on interpreting the results, make suggestions regarding the methodology, share experiences on the writing process, mention other ideas on the research topic, and so on.

Contributions to discussions of one another's projects will be evaluated, as well as the projects themselves.

Term Project (Week 1): Topic Idea

In addition to the weekly project, it is also time to start to think about your term project.

- Review the project outline and become familiar with what is required each week (Term Project Overview and Weekly Deliverables [9]). Timely submission of an appropriate topic suggestion (or suggestions) is important at this stage, since you will need to provide the entire class a project proposal that will be peer-reviewed during Lesson 5.

- Post a single paragraph that discusses the following three (3) things about your term project for this class. At this stage of the term project, keep the paragraph to less than 300 words.

- What is your term project's main "topic" of focus? Think broadly here (both geographically and conceptually).

- Why is your topic important, relevant, timely, etc.?

- Describe one (1) data set that you think you will need to collect for your term project. While you are at it, you should verify that you can access the data. Having access to the geographic scale, geographic extent, and temporal dimension of your data is a major hurdle that researchers encounter. Don't put off looking into acquiring your data until later in the course. Later may be too late for the term project.

Again, we are looking for a "big picture" description of your term project for this deliverable.

Deliverable

Post your topic idea to the 'Term Project: Topic Idea' Discussion Forum. One new topic for each student, please!

Even at this early stage, if you have constructive suggestions to make for other students, then by all means make them by posting comments in reply to the topic.

Questions?

Please use the Discussion - General Questions and Technical Help discussion forum to ask any questions now or at any point during this project.

Final Tasks

Lesson 1 Deliverables

- Complete the Lesson 1 quiz.

- Complete the Project 1 activities. This includes inserting maps and graphs into your write-up along with accompanying commentary. Submit your assignment to the 'Assignment: Week 1 Project' dropbox provided in Lesson 1 in Canvas.

- Post your project topic idea to the project topic discussion forum in Canvas.

NOTE: When you have completed this week's project, please submit it to the Canvas drop box for this lesson.

Reminder - Complete all of the Lesson 1 tasks!

You have reached the end of Lesson 1! Double-check the to-do list on the Lesson 1 Overview page [10] to make sure you have completed all of the activities listed there before you begin Lesson 2.

Additional Resources

For those of you who work with environmental data, this article might be of interest:

Dark, S. J. & D. Bram. (2007). The modifiable areal unit problem (MAUP) in physical geography. Progress in Physical Geography, 31(5): 471-479.

L2: Spatial Data Analysis: Dealing with data

The links below provide an outline of the material for this lesson. Be sure to carefully read through the entire lesson before returning to Canvas to submit your assignments.

Lesson 2 Overview

Geographic Information Analysis (GIA) is an iterative process that involves integrating data and applying a variety of spatial, statistical, and visualization methods to better understand patterns and processes governing a system.

Learning Outcomes

At the successful completion of Lesson 2, you should be able to:

- deal with various types of data;

- develop a data frame and structure necessary to perform analyses;

- apply various statistical methods;

- identify various spatial methods;

- develop a research framework and integrate both statistical and spatial methods; and

- document and communicate your analysis and findings in an efficient manner.

Checklist

Lesson 2 is one week in length. (See the Calendar in Canvas for specific due dates.) The following items must be completed by the end of the week. You may find it useful to print this page out first so that you can follow along with the directions.

| Step | Activity | Access/Directions |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Work through Lesson 2 | You are in Lesson 2 online content now. Be sure to read through the online lesson material carefully. |

| 2 | Reading Assignment | Before we go any further, you need to complete all of the readings for this lesson.

|

| 3 | Weekly Assignment | Project 2: Exploratory Data Analysis and Descriptive Statistics in R |

| 4 | Term Project | Submit a more detailed project proposal (1 page) to the 'Term Project: Preliminary Proposal' discussion forum. |

| 5 | Lesson 2 Deliverables |

|

Questions?

Please use the 'Discussion - Lesson 2' forum to ask for clarification on any of these concepts and ideas. Hopefully, some of your classmates will be able to help with answering your questions, and I will also provide further commentary where appropriate.

Spatial Data Analysis

Required Reading:

Read Chapter 1: "Introduction to Statistical Analysis in Geography," from Rogerson, P.A. (2001). Statistical Methods for Geography. London: SAGE Publications. This text is available as an eBook from the PSU library [11] (make sure you are logged in to your PSU account) and you can download and save a pdf of this chapter (or others) to your computer. You can skip over the section about analysis in SPSS.

Spatial analysis:

Refers to the "general ability to manipulate spatial data into different forms and extract additional meaning as a result" (Bailey 1994, p. 15) using a body of techniques "requiring access to both the locations and the attributes of objects" (Goodchild 1992, p. 409). This means spatial analysis must draw on a range of quantitative methods and requires the integration and use of many types of data and methods (Cromley and McLafferty 2012).

Where and how to start?

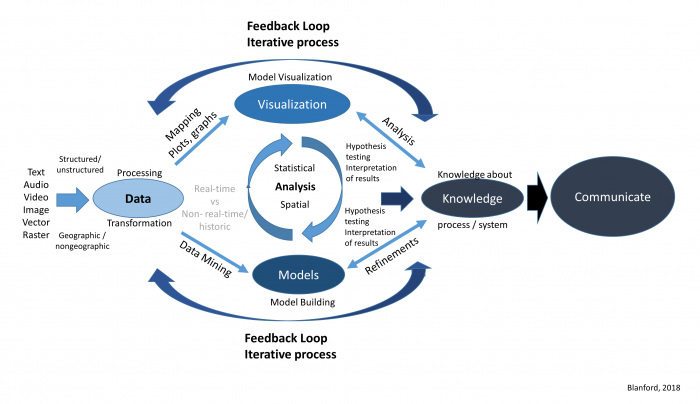

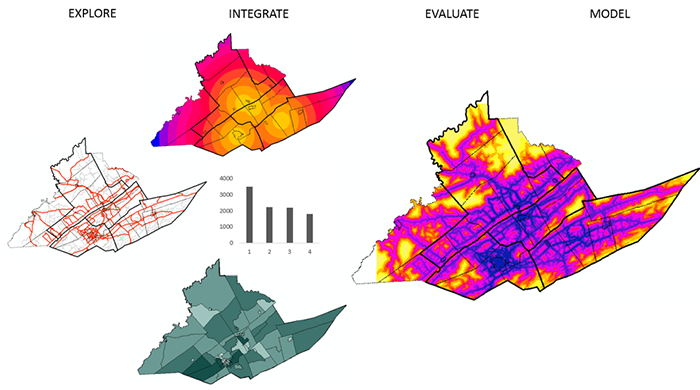

In Figure 2.0, we provided an overview of the process involved, now we will provide some of the details to get you familiar with the research process and the types of methods you may be using to perform your analysis.

Research framework

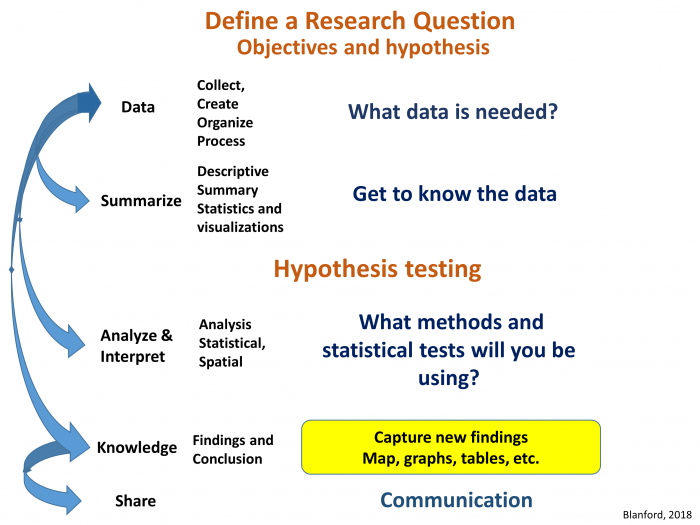

Where and how do we start to analyze our data? Analyzing data whether it is spatial or not is an iterative process that involves many different components (Figure 2.1). Depending on what questions we have in mind, we will need some data. Next, we will need to get to know our data so that we can understand its limitations, identify transformations required to produce a valid analysis, and better grasp the types of methods we will be able to use. Next, we will want to refine our hypothesis and then perform our analysis, interpret our results, and share our findings.

Statistical and Spatial Analysis

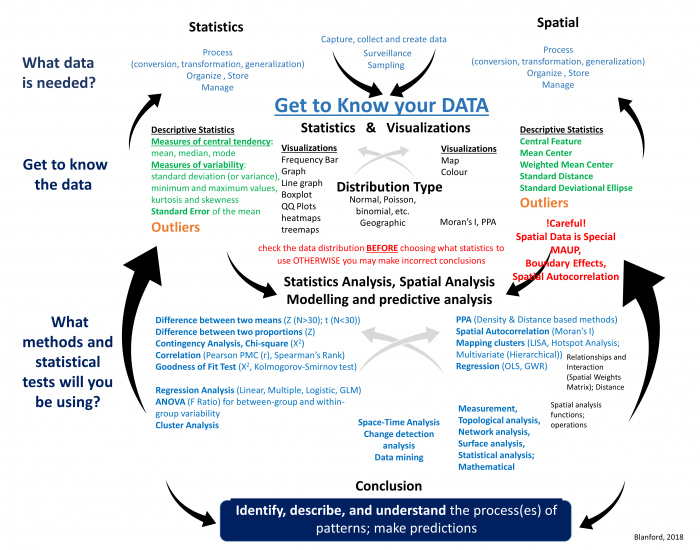

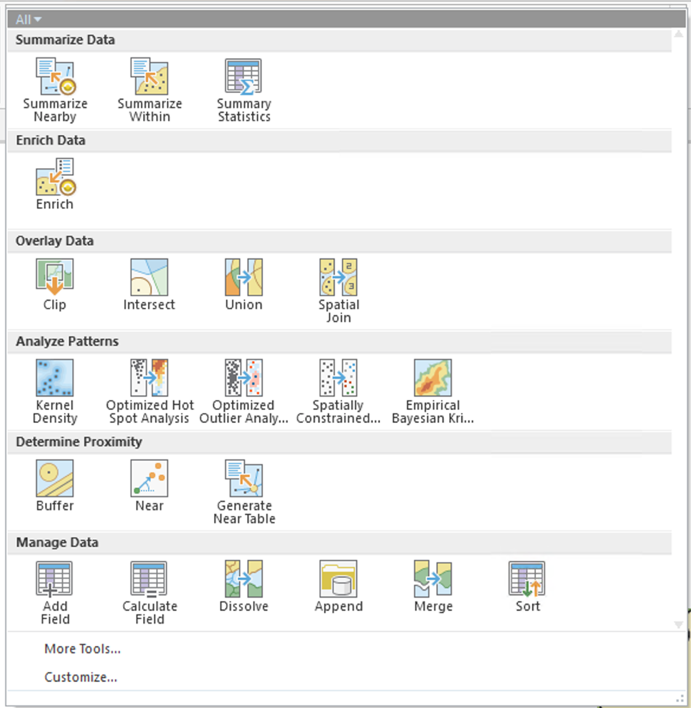

Now that you have an understanding of the research process, let’s start to familiarize ourselves with the different types of statistical and spatial analysis methods that we may need to use at each stage of the process (Figure 2.2). As you can see from Figure 2.2, statistical and spatial analysis methods are intertwined and often integrated. I know this looks complex, and for many of you the methods are new, but by the end of this course, you will have a better understanding of many of these methods and how to integrate them as you require spatial and/or statistical methods.

- Data: Determine what data is needed. This may require collecting data or obtaining third-party data. Once you have the data, it may need to be cleaned, processed (transformed, aggregated, converted, etc.), organized, and stored so that it is easy to manage, update, and retrieve for later analyses.

- Data: Get to know the data. This is an important step that many people ignore. All data has issues of one form or another. These issues are based on how the dataset was collected, formatted, and stored. Before you moving forward with your analysis, it is vital to understand

- What are a dataset's limitations? For example, you may be interested in learning about the severity of a disease across a region. The dataset you obtained contains count data (total number of cases). This count data will not give you an overall picture of the disease's impact and severity since one should adjust the case count according to the underlying population distribution (create a percent of total or incidence rate).

- Determine the usefulness of a dataset. Look at the data and determine if that data will fit your needs. For example, you may have obtained point data, but your analysis needs to operate on area-based data. Is the conversion between point to area-based data an appropriate way to answer your research question?

- Learn how the data are structured. Spreadsheets are convenient ways to store and share data. But how is that data arranged inside the spreadsheet? The data that you need may be there but the formatting is not advantageous (e.g., rows and columns need to be switched, dates need to be sequentially ordered, attributes need to be combined, etc.).

- identify any outliers. To better understand and explore the data, you can use descriptive spatial and non-spatial statistical methods as well as visualize the data either in graphs or plots as well as in the form of a map. Outliers may be signs of data entry errors or data that are atypical and depending on the intended statistical test may need to be removed from the data listing.

- Spatial Analysis and Statistical Methods. As you work through the analysis, you will use a variety of methods that are statistical, spatial, or both, as you can see from Figure 2.2. In the upcoming weeks, we will be using many of these methods starting with Point Pattern Analysis (PPA) in Lesson 3, spatial autocorrelation analysis (Lesson 4), regression analysis (Lesson 5), and the use of different spatial functions for performing spatial analysis (Lessons 6-Lesson 8). Remember, this is an iterative process that will likely require the use of one or more of the methods summarized in the diagram that are either traditional statistical methods (on the left) or a variety of spatial methods (on the right). In many cases, we will likely move back and forth between the different components (up and down) as well as between the left and right sides.

- Communication. Lastly, an important part of any research process is communicating your findings effectively. There are a variety of ways that we can do this, using web-based tools and integration of different visualizations.

Now that you have been introduced to the research framework and have an idea of some of the methods you will be learning about, let’s cover the basics so that we are all on the same page. We will start with data, then spatial analysis, and end with a refresher on statistics.

Data

Required Reading:

Read Chapter 2.2, pages 23-37 from the course text.

Data comes in many forms, structured and unstructured, and is obtained through a variety of sources. No matter its source or form, before the data can be used for any type of analysis, it must be assessed and transformed into a framework that can then be analyzed efficiently.

Some Special Considerations with Spatial Data [Rogerson Text, 1.6]

There shouldn't be anything new to anyone in this class in these pages. Since analysis is almost always based on data that suffer from some or all of these limitations, these issues have a big effect on how much we can learn from spatial data, no matter how clever the analysis methods we adopt become.

The separation of entities from their representation as objects is important, and the scale-dependence issue that we read about in Lesson 1 is particularly important to keep in mind. The scale dependence of all geographic analysis is an issue that we return to frequently.

GIS Analysis, Spatial Data Manipulation, and Spatial Analysis

From Figure 2.2, it is clear that spatial analysis requires a wide variety of analytical methods (statistical and spatial).

Spatial analysis functions fall into five classes that include: measurement, topological analysis, network analysis, surface analysis and statistical analysis (Cromley and McLafferty 2012, p. 29-32) (Table 2.0).

| Function Class | Function | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Measurement | Distance, length, perimeter, area, centroid, buffering, volume, shape, measurement scale conversion | Allows users to calculate straight-line distances between points, distances along paths, arcs, or areas. Distance as a measure of separation in space is a key variable used in many kinds of spatial analysis and is often an important factor in interactions between people and places. |

| Topological analysis | Adjacency, polygon overlay, point-in-polygon, line-in-polygon, dissolve, merge, clip, erase, intersect, union, identity, spatial join, and selection | Used to describe and analyze the spatial relationships among units of observation. Includes spatial database overlay and assessment of spatial relationships across databases, including map comparison analysis. Topological analysis functions can identify features in the landscape that are adjacent or next to each other (contiguous). Topology is important in modeling connectivity in networks and interactions. |

| Network and location analysis | Connectivity, shortest path analysis, routing, service areas, location-allocation modeling, accessibility modeling | Investigates flows through a network. Network is modeled as a set of nodes and the links that connect the nodes. |

| Surface analysis | Slope, aspect, filtering, line-of-sight, viewsheds, contours, watersheds; surface overlays or multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) | Often used to analyze terrain and other data that represent a continuous surface. Filtering techniques include smoothing (remove noise from data to reveal broader trends) and edge enhancement (accentuate contrast and aids in the identification of features). Or to perform raster-based modeling where it is necessary to perform complex mathematical operations that combine and integrate data layers (e.g., fuzzy logic, overlay, and weighted overlay methods; dasymetric mapping). |

| Statistical analysis | Spatial sampling, spatial weights, exploratory data analysis, nearest neighbor analysis, global and local spatial autocorrelation, spatial interpolation, geostatistics, trend surface analysis. | Spatial data analysis is closely tied to spatial statistics and is influenced by spatial statistics and exploratory data analysis methods. These methods analyze information about the relationships being modeled based on attributes as well as their spatial relationships. |

Although maps are used to present research results (when they present known results and are represented using public, low-interaction devices), many more maps are impermanent, exploratory devices, and with the increased use of interactive web-based data graphs and maps, often driven by dynamically changing data, this is even more so the case.

With this, there is an ever-increasing need for spatial analysis, particularly since much of the data collected today contains some form of geographic attribute and every map tells a story… or does it? It is easy to feel that a pattern is present in a map. Spatial analysis allows us to explore the data, develop a hypothesis, and test that visual insight in a systematic, more reliable way.

The important point at this stage is to get used to thinking of space and spatial relations in the terms presented here — distance [12], adjacency [13], interaction [14], and neighborhood [15]. The interaction weight idea is particularly commonly used. You can think of interaction as an inverse distance measure: near things interact more than distant things. Thus, it effectively captures the basic idea of spatial autocorrelation [16].

Summarizing Relationships in Matrices [Lloyd text, section 2.2]

This week's readings discuss some of the ways matrices are used in spatial analysis. You'll notice that distances and adjacencies appear in Table 2.0. At this stage, you only need to get the basic idea that distances, adjacencies (or contiguities), or interactions can all be recorded in a matrix [17] form. This makes for very convenient mathematical manipulation of a large number of relationships among geographic objects. We will see later how this concept is useful in point pattern analysis (Lesson 3), clustering and spatial autocorrelation (Lesson 4), and interpolation (Lesson 6).

Statistics, a refresher

Statistical methods, as will become apparent during this course, play an important role in spatial analysis and are behind many of the methods that we regularly use. So to get everyone up to speed, particularly if you haven’t used stats recently, we will review some basic ideas that will be important through the rest of the course. I know the mention of statistics makes you want to close your eyes and run the other direction .... but some basic statistical ideas are necessary for understanding many methods in spatial analysis. An in-depth understanding is not necessary, however, so don't get worried if your abiding memory of statistics in school is utter confusion. Hopefully, this week, we can clear up some of that confusion and establish a firm foundation for the much more interesting spatial methods we will learn about in the weeks ahead. We will also get you to do some stats this week!

You have already been introduced to some stats earlier on in this lesson (see Figures 2.0-2.3). Now, we will focus your attention on the elements that are particularly important for the remainder of the course. "Appendix A: The elements of Statistics," linked in the additional readings list for this lesson in Canvas, will serve as a good overview (refresher) for the basic elements of statistics. The section headings below correspond to the section headings in the reading.

Required Reading:

Read the Appendix A reading provided in Canvas (see Geographic Information Analysis [18]), especially if this is your first course in statistics or it has been a long time since you took a statistics class. This reading will provide a refresher on some basic statistical concepts.

A.1. Statistical Notation

One of the scariest things about statistics, particularly for the 'math-phobic,' is the often intimidating appearance of the notation used to write down equations. Because some of the calculations in spatial analysis and statistics are quite complex, it is worth persevering with the notation so that complex concepts can be presented in an unambiguous way. Really, understanding the notation is not indispensable, but I do hope that this is a skill you will pick up along the way as you pursue this course. The two most important concepts are the summation symbol capital sigma (Σ), and the use of subscripts (the i in xi).

I suggest that you re-read this section as often as you feel the need, if, later in the course, 'how an equation works' is not clear to you. For the time being, there is a question in the quiz to check how well you're getting it.

A.2. Describing Data

The most fundamental application of statistics is simply describing large and complex sets of data. From a statistician's perspective, the key questions are:

- What is a typical value in this dataset?

- How widely do values in the dataset vary?

... and following directly from these two questions:

- What qualifies as an unusually high or low value in this dataset?

Together, these three questions provide a rough description of any numeric dataset, no matter how complex it is in detail. Let's consider each in turn.

Measures of central tendency such as the mean and the median provide an answer to the 'typical value' question. Together, these two measures provide more information than just one value, because the relationship between the two is revealing. The important difference between them is that, the mean is strongly affected by extreme values while the median is not.

Measures of spread are the statistician's answer to the question of how widely the values in a dataset vary. Any of the range, the standard deviation, or the interquartile range of a dataset allows you to say something about how much the values in a dataset vary. Comparisons between the different approaches are again helpful. For example, the standard deviation says nothing about any asymmetry in a data distribution, whereas the interquartile range—more specifically the values of Q25 and Q75—allows you to say something about whether values are more extreme above or below the median.

Combining measures of central tendency and of spread enables us to identify which are the unusually high or low values in a dataset. Z scores standardize values in a dataset to a range such that the mean of the dataset corresponds to z = 0; higher values have positive z scores, and lower values have negative z scores. Furthermore, values whose z scores lie outside the range ±2 are relatively unusual, while those outside the range ±3 can be considered outliers. Box plots provide a mechanism for detecting outliers, as discussed in relation to Figure A.2.

A.3. Probability Theory

Probability is an important topic in modern statistics.

The reason for this is simple. A statistician's reaction to any observation is often along the lines of, "Well, your results are very interesting, BUT, if you had used a different sample, how different would the answer be?" The answer to such questions lies in understanding the relationship between estimates derived from a sample and the corresponding population parameter, and that understanding, in turn, depends on probability theory.

The material in this section focuses on the details of how probabilities are calculated. Most important for this course are two points:

- the definition of probability in terms of the relative frequency of events (eqns A.18 and A.19), and

- that probabilities of simple events can be combined using a few relatively simple mathematical rules (eqns A.20 to A.26) to enable calculation of the probability of more complex events.

A.4. Processes and Random Variables

We have already seen in the first lesson that the concept of a process is central to geographic information analysis (look back at the definition on page 3).

Here, a process is defined in terms of the distribution of expected outcomes, which may be summarized as a random variable. This is very similar to the idea of a spatial process, which we will examine in more detail in the next lesson, and which is central to spatial analysis.

A.5. Sampling Distributions and Hypothesis Testing

The most important result in all of statistics is the central limit theorem. How this is arrived at is unimportant, but the basic message is simple. When we use a sample to estimate the mean of a population:

- The sample mean is the best estimate for the population mean, and

- If we were to take many different samples, each would produce a different estimate of the population mean, and these estimates would be normally distributed, and

- The larger the sample size, the less variation there is likely to be between different samples.

Item 1 is readily apparent: What else would you use to estimate the population mean than the sample mean?!

Item 2 is less obvious, but comes down to the fact that sample means that differ substantially from the population mean are less likely to occur than sample means that are close to the population mean. This follows more or less directly from Item 1; otherwise, there would be no reason to choose the sample mean in making our estimate in the first place.

Finally, Item 3 is a direct outcome of the way that probability works. If we take a small sample, then it is prone to wide variation due to the presence of some very low or very high values (like the people in the bar example). On the other hand, a very large sample will also vary with the inclusion of extreme values, but overall is much more likely to include both high and low values.

Try This! (Optional)

Take a look at this animated illustration of the workings of the central limit theorem [19] from Rice University.

The central limit theorem provides the basis for calculation of confidence intervals, also known as margins of error, and also for hypothesis testing.

Hypothesis testing may just be the most confusing thing in all of statistics... but, it really is very simple. The idea is that no statistical result can be taken at face value. Instead, the likelihood of that result given some prior expectation should be reported, as a way of inferring how much faith we can place in that expectation. Thus, we formulate a null hypothesis, collect data, and calculate a test statistic. Based on knowledge of the distributional properties of the statistic (often from the central limit theorem), we can then say how likely the observed result is if the null hypothesis were true. This likelihood is reported as a p-value or probability. A low probability indicates that the null hypothesis is unlikely to be correct and should be rejected, while a high value (usually taken to mean greater than 0.05) means we cannot reject the null hypothesis.

Confusingly, the null hypothesis is set up to be the opposite of the theory that we are really interested in. This means that a low p-value is a desirable result, since it leads to rejection of the null, and therefore provides supporting evidence for our own alternative hypothesis.

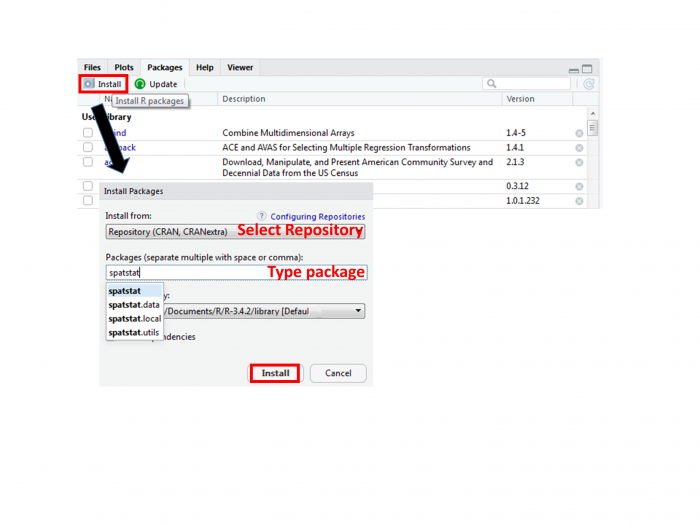

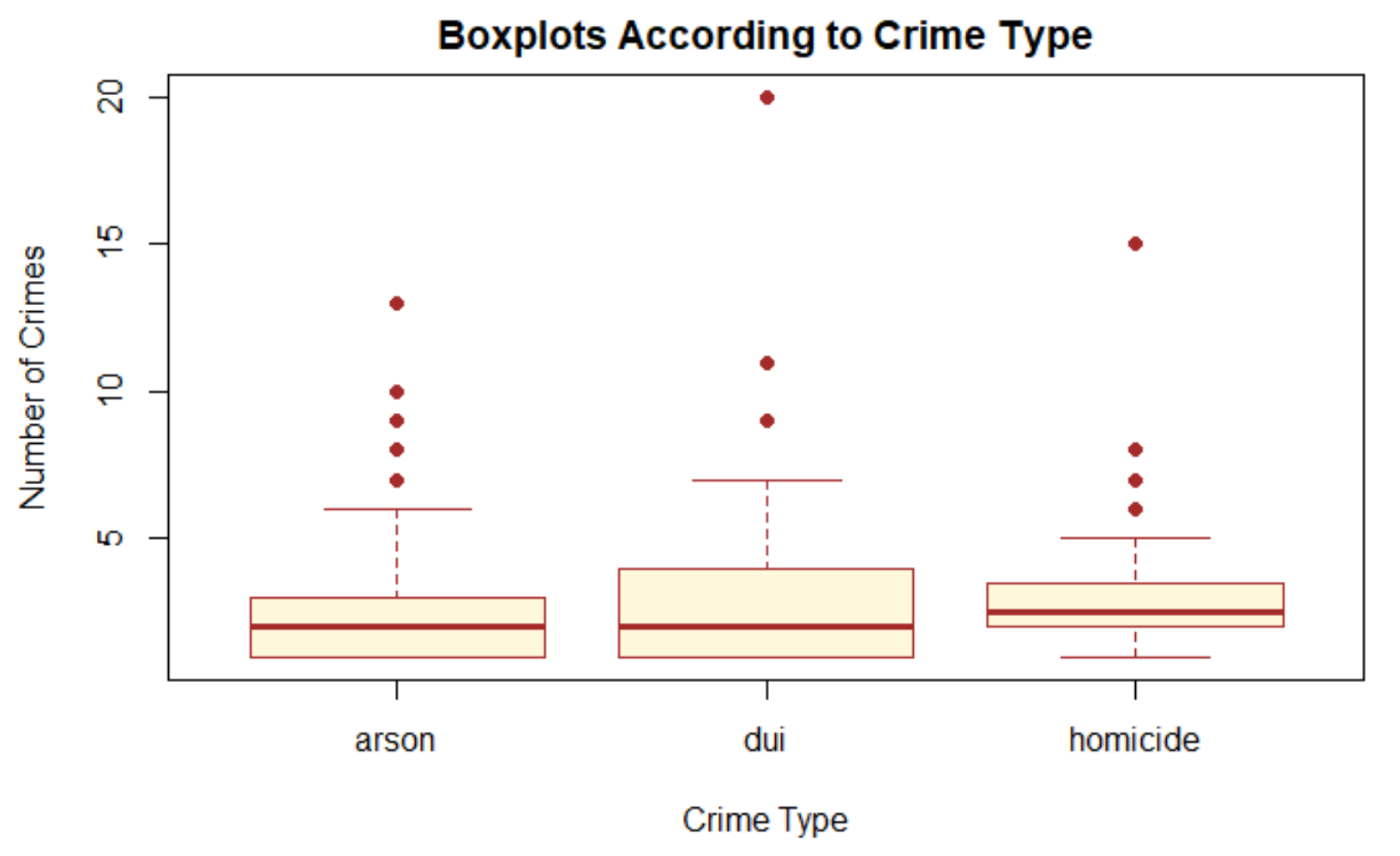

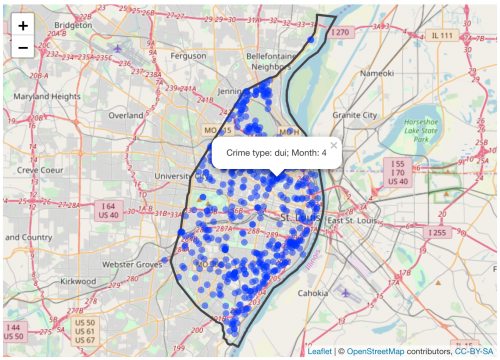

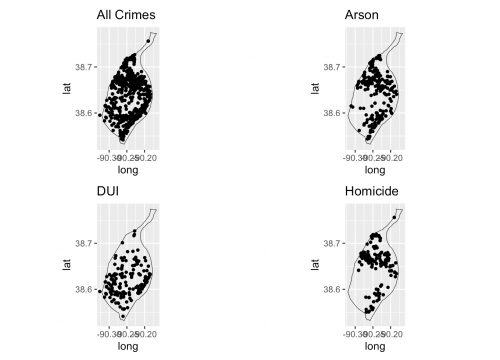

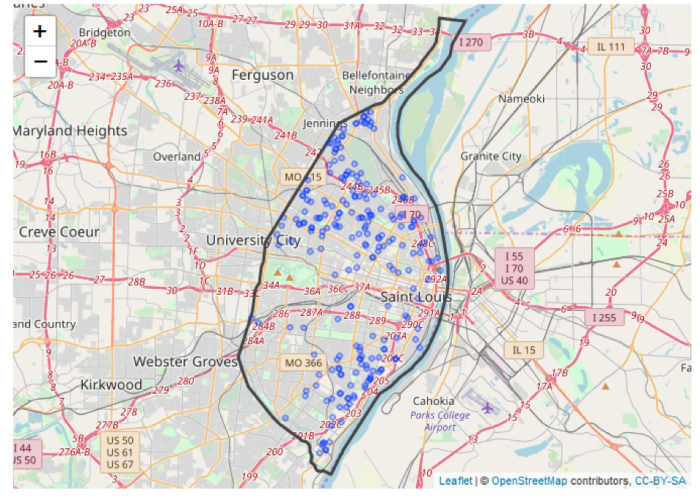

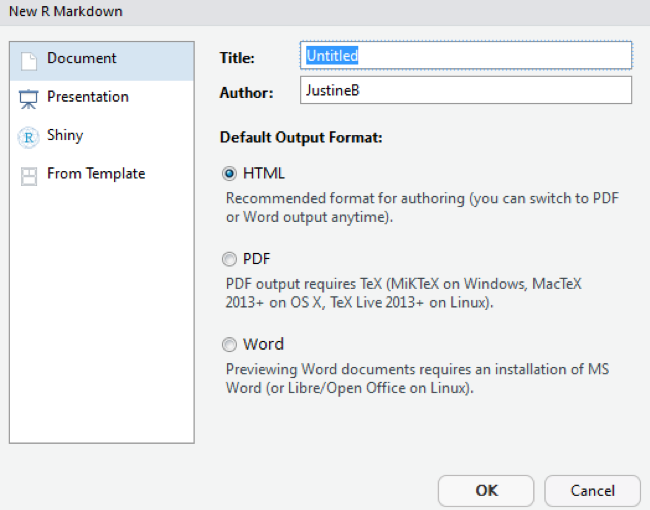

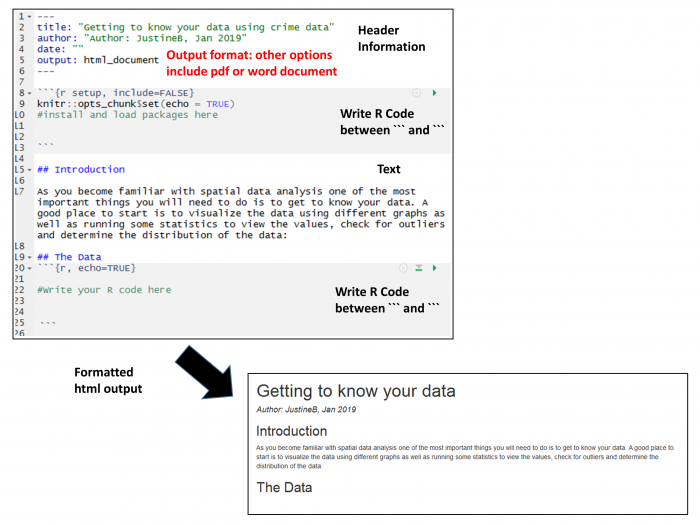

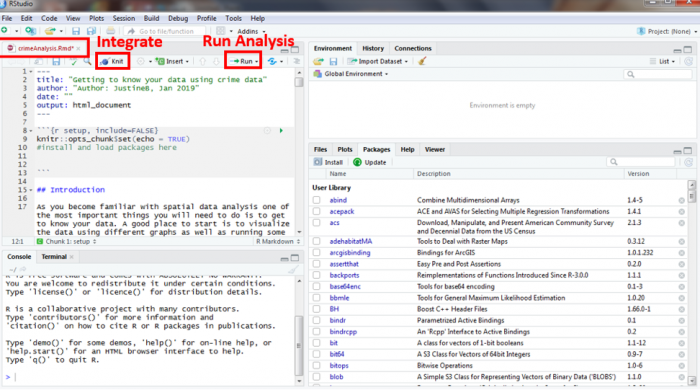

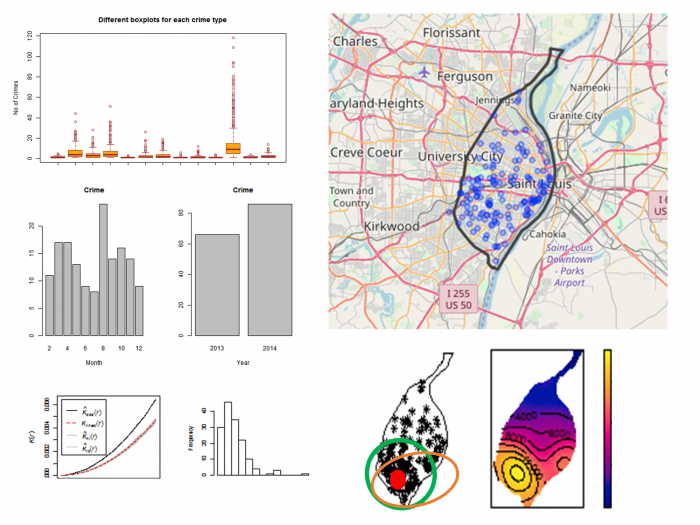

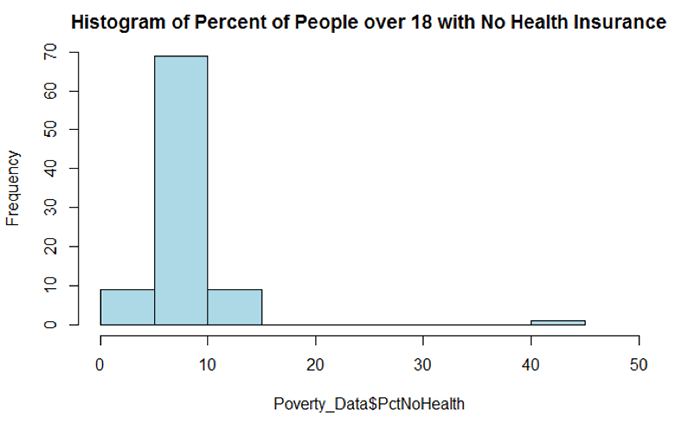

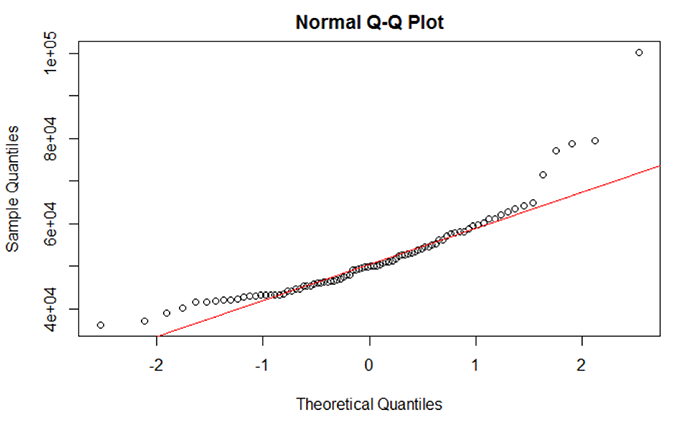

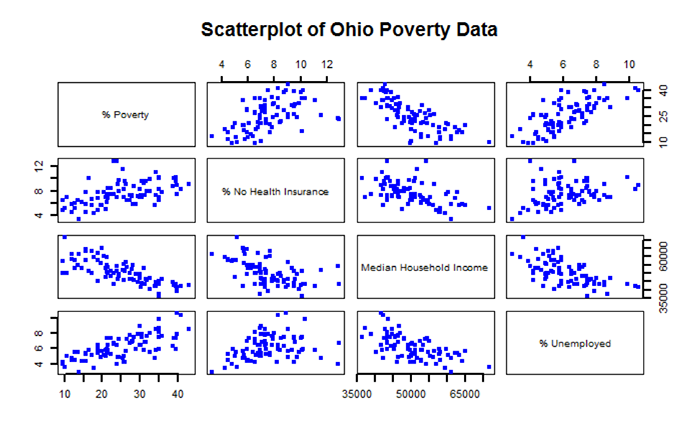

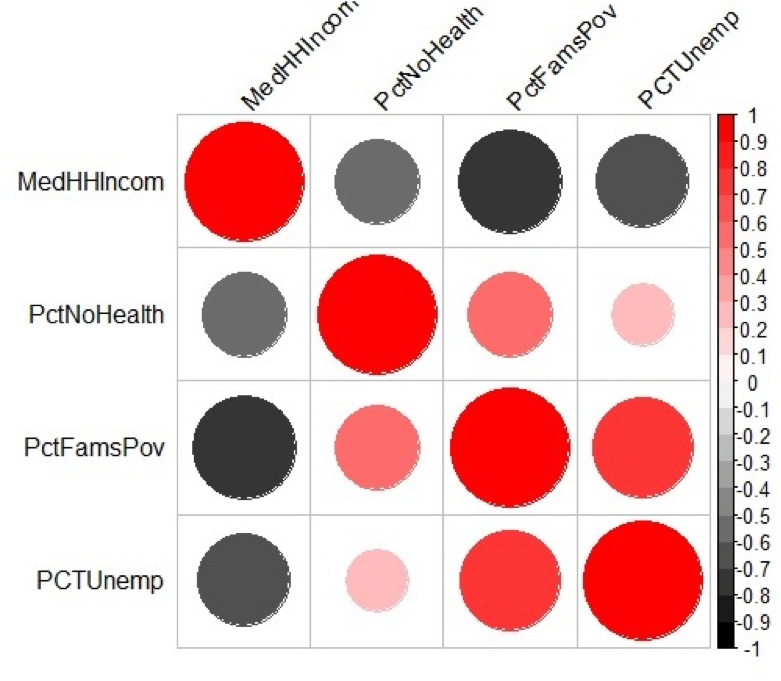

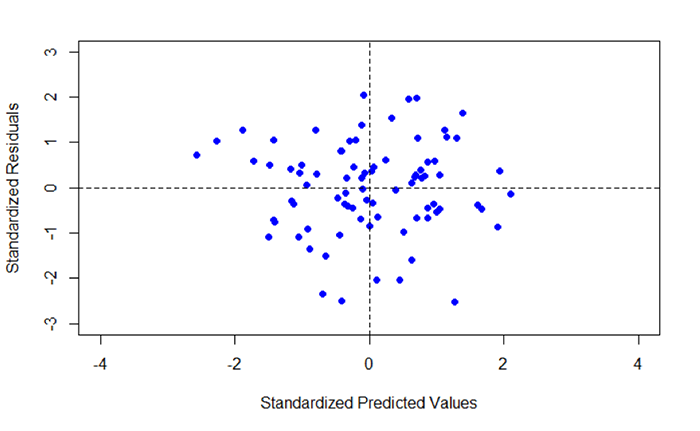

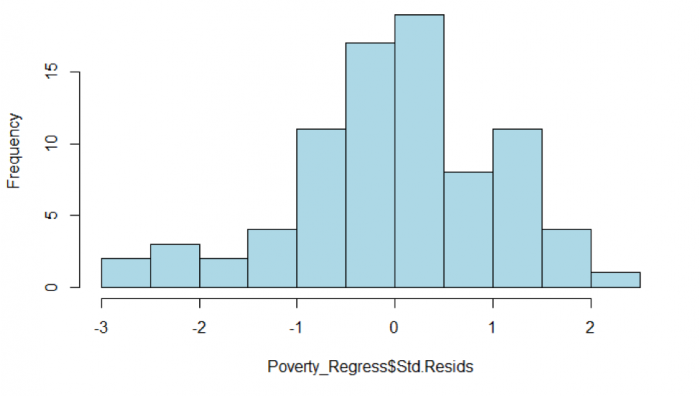

Visualizing the Data