Lessons

This is the course outline.

Lesson 1: Introduction to GIS-T

Learning Outcomes

What will we learn?

By the end of Lesson 1, you should be able to:

- characterize the relationship between GIS and transportation and explain why GIS-T is such an active field;

- discuss some of the challenges and opportunities for GIS-T in the 21st century;

- list some modes of transportation and discuss the meaning and significance of modal competition, modal shift, and containerization;

- state the mission and describe some of the current initiatives of the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT);

- describe some of the geographic areas the Census Bureau uses to aggregate and disseminate data.

1.1 Introduction to GIS-T

Among the many areas and disciplines to which GIS has been applied, transportation has been particularly fertile ground, and the development of specialized GIS applications has been an area which has seen a lot of activity. This important interdisciplinary field is commonly referred to as GIS-T. The significance of this field is evidenced by the fact that there are two conferences devoted to it, one annual and one biennial. Each year the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) sponsors the annual GIS for Transportation Symposium [1]. The symposium draws over 400 registrants from federal, state, and local government and the private sector. The Urban and Regional Information Systems Association (URISA) sponsors a conference called GIS in Transit [2]which is held every other year. The 10th GIS in Transit conference was held last year.

A key reason that GIS-T is so important is that transportation is a huge industry upon which many other industries depend. In 2015, the federal government spent 85 billion dollars on transportation-related initiatives. That represented 2.22% of our total federal budget for 2015. The National Priority Project (NPP) website [3] presents some interesting charts which put federal transportation spending in perspective.

Additional Learning

In their own words, the NPP “is a national non-profit, non-partisan research organization dedicated to making complex federal budget information transparent and accessible so people can prioritize and influence how their tax dollars are spent.” Their website also offers a number of very educational videos [4] if you’d like to understand our national budget, deficit, and debt.

In addition to federal dollars, there are many billions of state and local dollars spent on transportation. If you want to see how states are using transportation dollars, the Track State Dollars website [5] gives you access to data for each state.

In the U.S., federal agencies have helped to promote GIS use for transportation analysis purposes through geospatially-enabled initiatives such as the U.S. Census Bureau’s TIGER program and the Federal Highway Administration’s Highway Performance Monitoring System (HPMS). Software vendors have continually updated and improved their GIS products to include additional GIS-T functionality and tools. Today, GIS-T is an integral part of transportation operations around the world.

The natural synergy between GIS and transportation is at least in part due to the fact that transportation is inherently spatial, and while it’s true that GIS plays an important role in transportation, one can also argue that transportation plays an important role in GIS. Transportation features are frequently included on maps for context and orientation even when the fundamental purpose of the map has little or nothing to do with transportation. Take a few minutes to review this recent blog [6] from GeoSpatial World which briefly examines some important applications of GIS to transportation. In this course, we'll cover these application areas as well as many others.

1.2 Overview of the Transportation Industry

Broadly speaking, the field of transportation is concerned with the transport of people and goods. To appreciate the value that GIS brings to transportation it is necessary to develop an understanding of the various forms of transportation that exist and also the types of activities and problems which those in the field need to address.

Transportation Modes

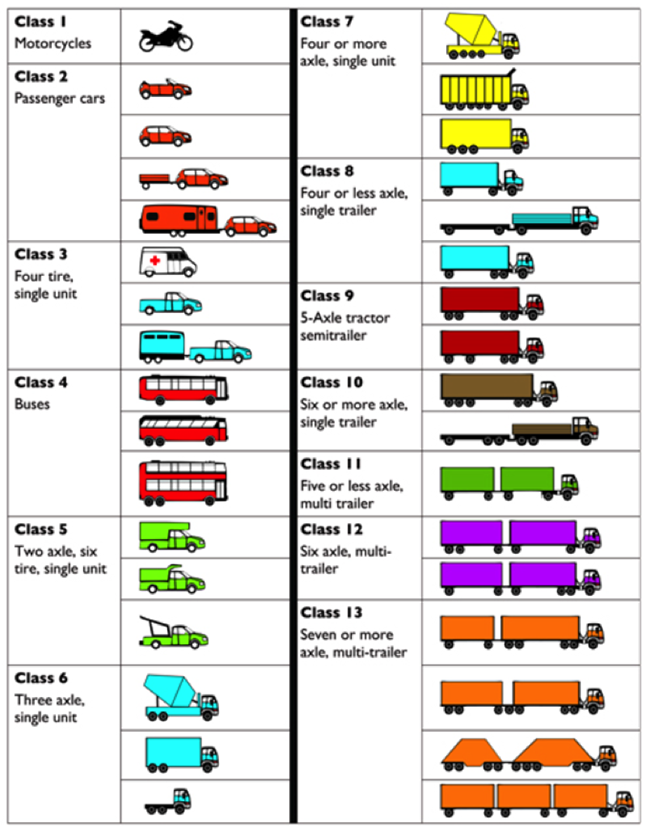

The different ways that people and freight can be transported are referred to as transportation modes. There are many different modes of transportation, and they can be differentiated and categorized in a number of ways. At a high level, we can divide transportation into the categories of air, land, sea, and space. We could further divide the land-based transportation into road, rail, pedestrian, bike, and pipeline, although one might rightfully argue that pipelines can run under the sea. Transportation modes are not always mutually exclusive and the specific modes we talk about often depend on the situation at hand. There have been many GIS applications which have been designed for a specific mode or for a group of closely related modes.

Transportation Processes and Activities

Just as we can categorize transportation according to the many modes of transportation which exist, we can think about transportation in terms of the many processes and activities which are performed in order to manage transportation infrastructure, vehicles, and operations. Some of these processes cut across modes and others are specific to a single mode or a few modes. These processes and activities include:

- infrastructure monitoring and maintenance;

- transportation planning and transit planning;

- property acquisition and management;

- vehicle tracking and logistics;

- highway safety analysis and improvement;

- traffic monitoring, modeling, and mitigation;

- screening projects for environmental impacts;

- dissemination of travel information to the public;

- reporting data to government agencies to secure funding;

- mobile data collection;

- routing and permitting of oversize overweight vehicles.

GIS-T plays an important role in enhancing the manner in which transportation organizations accomplish these processes and activities and, in some cases, allow organizations to perform functions which would simply not be possible without spatial technologies. GIS-T applications support evaluation of different scenarios, provide objective data for decision-making purposes, and promote the visualization of conditions.

GIS-T Techniques and Tools

GIS-T utilizes many mainstream geospatial tools and methods but it also employs a number of techniques which were borne out of the specialized needs of the transportation industry. These include:

- Conflation

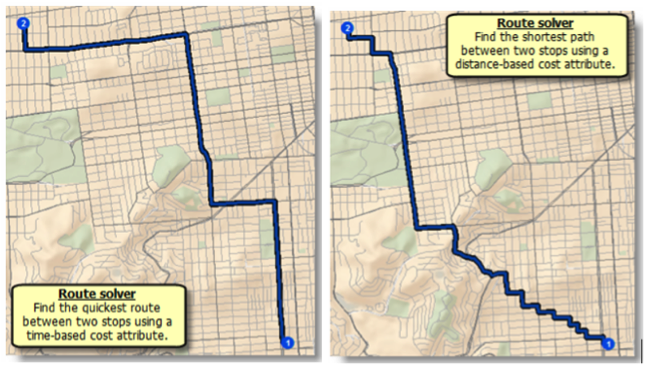

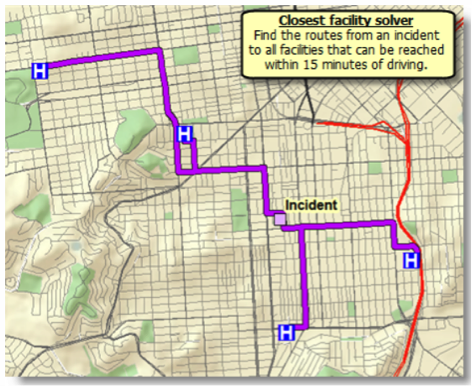

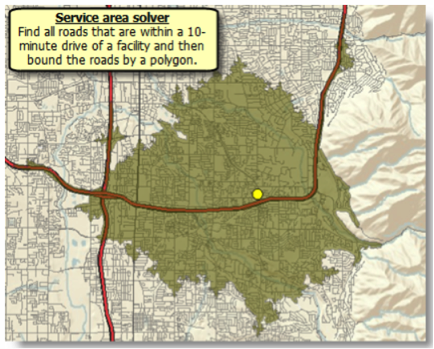

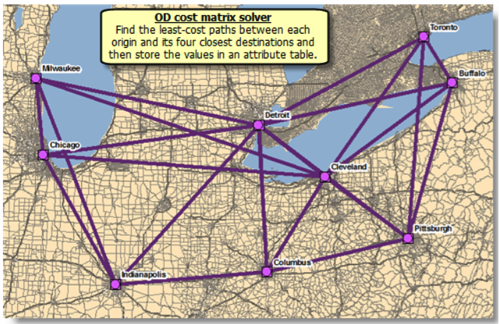

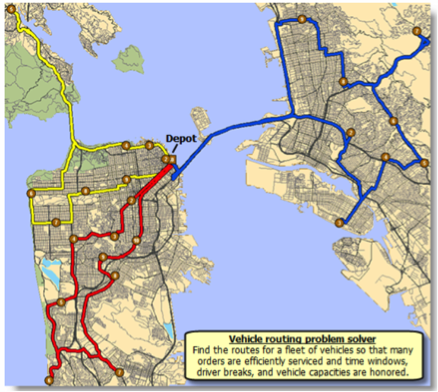

Conflation is a technique used to bring together adjacent or overlapping datasets which were collected at different times and have different levels of accuracy and precision. While the process of conflation in GIS is frequently applied to transportation networks, conflation can also be used to combine other types of features. - Network Analysis

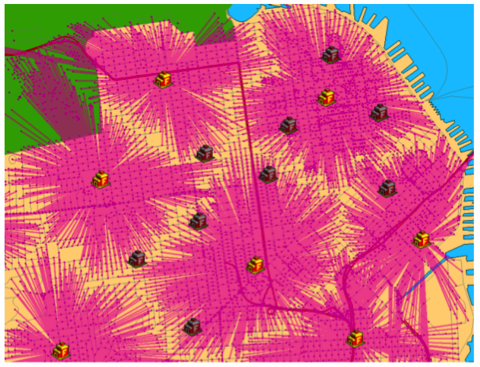

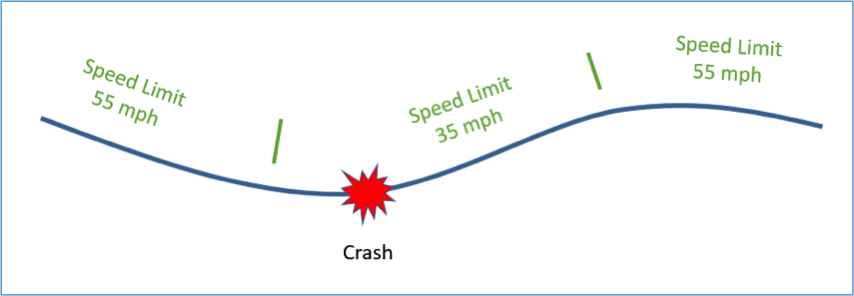

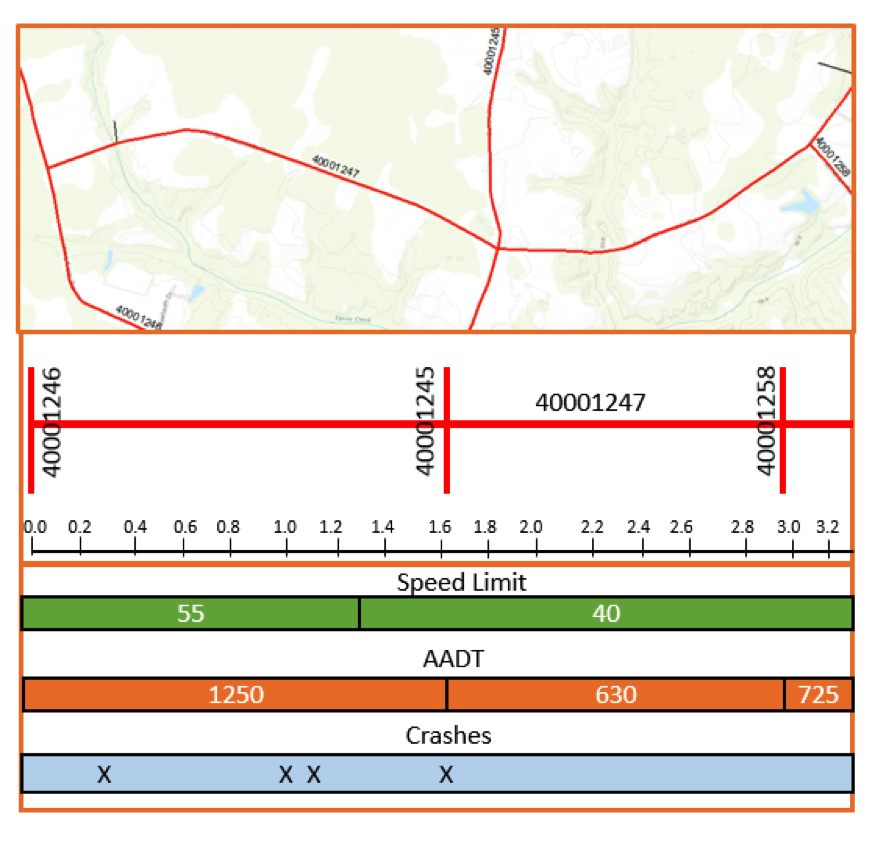

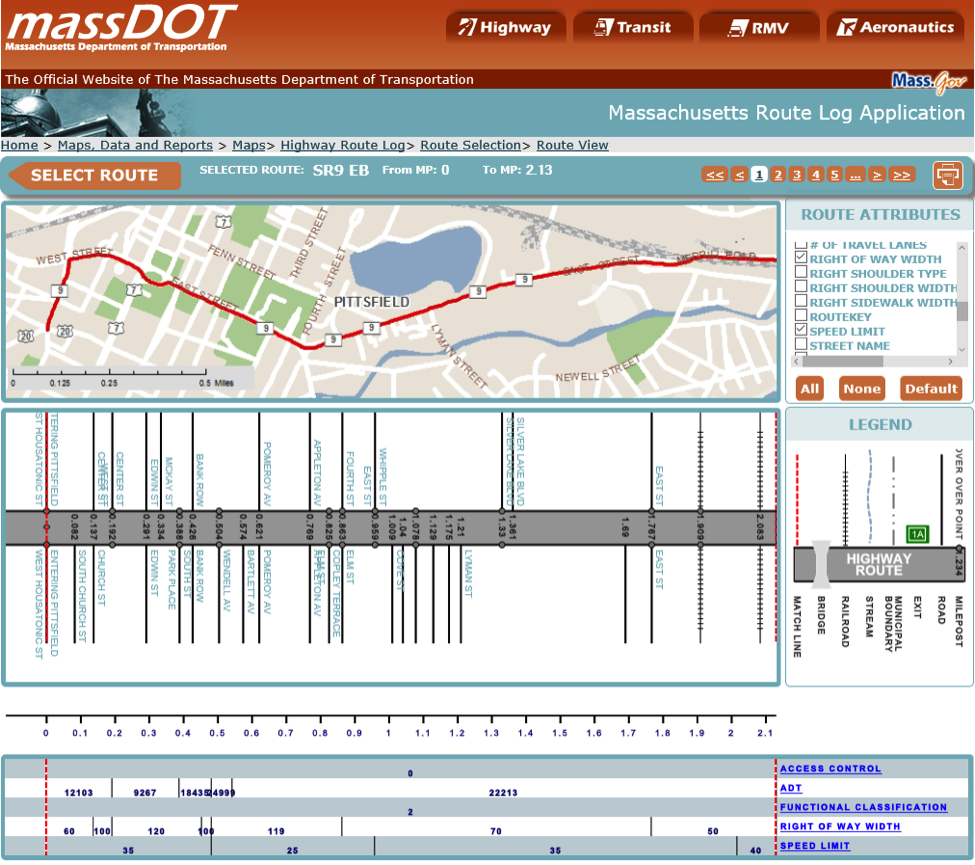

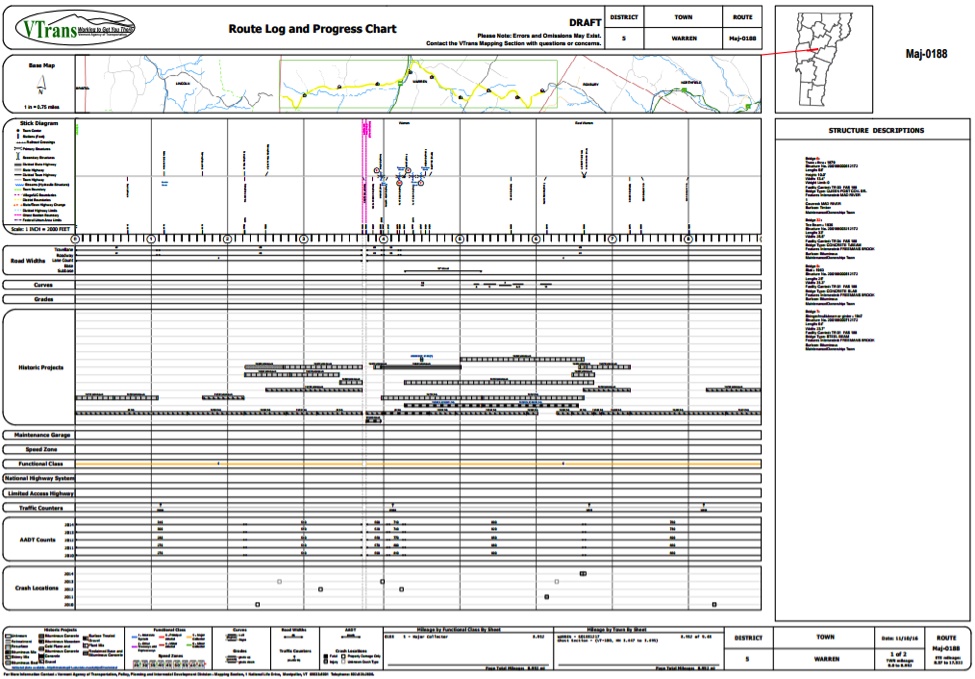

A roadway network is comprised of roads and intersections. In network terminology, the intersections are referred to as nodes, and the streets which connect the nodes are called edges. GIS-T commonly employs network analysis techniques to roadway networks to solve common transportation-related problems such as finding the best route between two points or determining the service area around a specific location (i.e., the area within which someone could reach the location of interest in a defined period of time). - Linear Referencing Systems

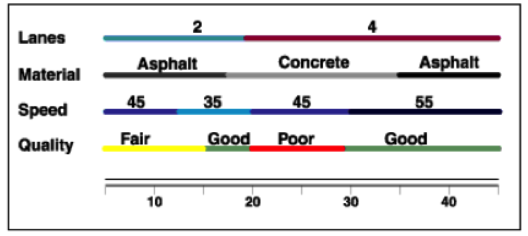

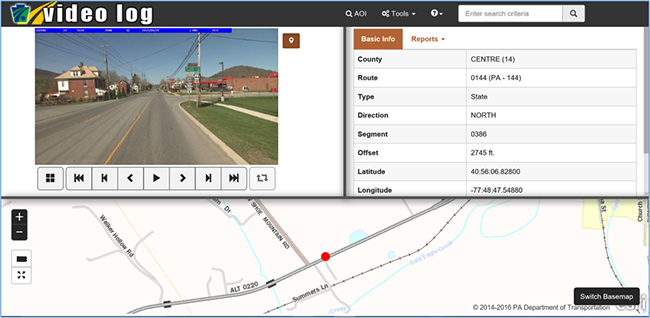

Linear referencing systems (LRS) are used to spatially reference the location of assets (e.g., bridges), occurrences (e.g., crashes), and roadway characteristics and administrative data (e.g., speed limits) by specifying the distance along a linear feature in a roadway network. Collectively, these attributes of a roadway are referred to as events. In this course we'll only consider the application of an LRS to roadway networks, they can be used in any linear network including pipelines and hydrologic networks. - Dynamic Segmentation

Dynamic segmentation is closely linked to LRS. In dynamic segmentation, we take the roadway events which are linearly referenced along roadways and transform them on the fly into spatial features. Taken together, LRS and dynamic segmentation allow us to effectively manage and utilize the myriad of attribute information associated with roadway networks. We will explore these techniques in detail in Lesson 6.

We will learn more about these techniques in upcoming lessons.

1.3 Getting to Know a Transportation Organization

This week, you’ll take some time to get to know perhaps the most significant transportation organization in the United States, the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT). The USDOT (established in 1966) is a cabinet-level department within the U.S. government which employs about 55,000 people and is responsible for maintaining and advancing the nation’s transportation systems and infrastructure.

A key function of the USDOT is to develop programs which implement transportation-related statutes. One of the most important statutes the USDOT is tasked with implementing relates to the funding of surface transportation. The latest surface transportation statute is known as the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act, which was signed into law by President Obama in December 2015.

The USDOT is comprised of a number of operating administrations and bureaus, each of which specializes in a specific area of transportation. Some of these divisions, along with the area of transportation they are responsible for, are listed below:

- Federal Highways Administration (FHWA)

Specializes in highway transportation - Federal Transit Administration (FTA)

Provides financial and technical assistance to public transit agencies - Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)

Regulates all aspects of civil and commercial aviation and operates a national system of air traffic control and navigation - Federal Railroad Administration (FRA)

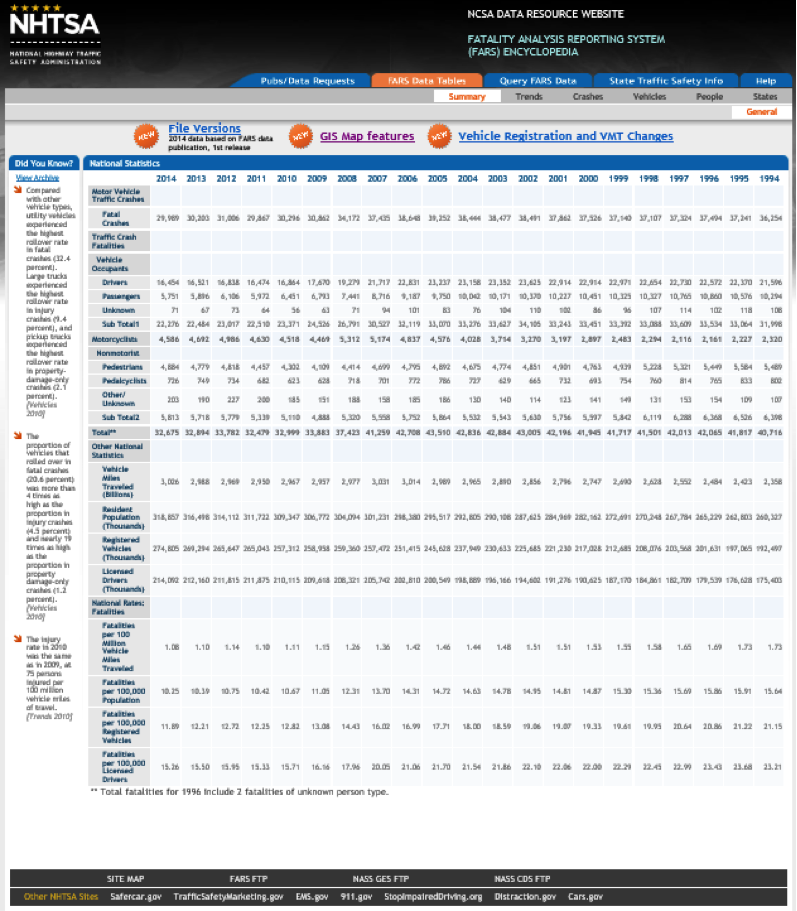

Enforces rail safety regulations and administers railroad assistance programs - National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA)

Specializes in reducing vehicle-related crashes

We’ll take a closer look at some of these USDOT divisions in later lessons.

Spend some time looking at the USDOT’s website [7] and try to learn some more about the organization and some of their current initiatives and activities. Also, spend some time learning about the Smart City Challenge which the USDOT kicked off in December 2015. This challenge was designed to promote innovative solutions to some of the biggest challenges our cities face and offered $50 million to the winning city, $40 million of which came from the USDOT and $10 million from a private partner. Here is a video where the USDOT provided information to city mayors across the county. (Note: the presentation doesn't begin until about 10 minutes into the recording and you may want to skip ahead to the 18-minute mark when former Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx begins to speak).

Video: Smart Cities Webcast (25:14)

KEVIN: Good afternoon. My name is Kevin Monroe, Deputy Assistant Secretary for governmental affairs here at the US Department of Transportation. Now, I want to welcome and thank you for joining us today for a webcast on the Smart City Challenge. Secretary Foxx will be joining us shortly, but right now I'd like to take the opportunity to introduce my colleague, Mark Dowd, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology. He will tell us more about the Smart City Challenge. Mark.

MARK: Hi, welcome. I'm going to take you through some of the details for the Smart City challenge to get you oriented as to what we're looking for. We'll be hearing from the secretary shortly. He is extremely excited about this challenge. As a former mayor, he is looking forward to hearing from his fellow mayors as to how to solve the issues that we identified in "Beyond Traffic".

Beyond Traffic, narrative identified the issues of moving people and moving goods, and so we decided that it would be good to reach out to cities and encourage them to put forward their most creative ideas on how to solve those problems using technology and innovation.

I want to take you through a little bit of the schedule. We have two phases: phase one and the most important part is the deadline coming up on February fourth. We are looking for cities to put forward their high-level, thirty-page ideas as to how to solve these issues using innovation and technology. The second phase when we down select to 5 will be we will move through the process of awarding the five finalists 100,000 dollars and selecting the finalist who will receive the 50 million dollars.

I think I'll take you through a little bit of what we're looking for. We are looking for a medium-sized city, although we accept applications from all cities. This is generally what we're looking for, from in terms of particularity. We're looking for a population between 200,000 and 850,000 using 2010 census data, a dense urban population that's typical for a medium-sized city. We're looking for leadership in the city that is committed to carrying this through for the three years of the program. There are a number of different aspects of smart cities that people talk about. We thought we'd talk a little bit about from a smart city perspective what we're looking for in the transportation sector. There are a number of technologies on the left-hand side that will feed into the solutions and then, on the right-hand side are the benefits that we're looking for. We tried to lay out our vision of what of what this would look like and we tried to do it with 12 vision elements that are identified in the notice of funding opportunity. The highest priority is the technology elements that are urban automation, connected vehicles, and sensor-based infrastructure. The second level priority is the innovative approaches to urban transportation and these include the sharing economy, Open Data, urban analytics, connected involved citizens, and smart strategic business partnerships. Lastly are the other three smart city elements that are in each architecture and standards, smart land use, and low-cost, efficient ICT.

In your thirty-page, high-level application, we're looking for certain similarities in all the applications that we lay out what we're looking for in our narrative description. The evaluation criteria which will drive a lot of the narrative that includes a lot of what we talked about earlier, which is including population size, etc.

I think is important to take us through a couple of the critical deadlines that we're looking for. The applications are due on February 4th at 3 p.m., and then once we receive the application, we'll go through a fairly rigorous procurement process to down select to the five finalists. We'll announce the finalists in March 2016. Soon thereafter, we will issue $100,000 to each of the finalists to help them get their applications in in good form to compete for the final award. The final award will be issued in June 2016 to the winning city.

I'm sure you have additional questions or concerns and we'll have various opportunities for you to interact with the department on how to solve those problems and those issues that you have. We have an in-person Smart City forum that is on December 15th here at the Department of Transportation between nine o'clock and four o'clock. We have about 350, 400 people already signed up for this in-person meeting and then following that we'll have a number of technical advisories. We'll do data, architecture, and standards on December 16th, connected vehicles and automation December 17th. We'll discuss sharing economy, user-focused mobility on December 18th, and then we'll help you navigate the smart city challenge application process we'll be out shortly with that announcement.

I'm sure you have questions. Please don't hesitate to send them to smartcitychallenge@dot.gov [8], and we will continue to update our website with additional dates and additional information at transportation.gov/smartcity.

BRYNA: Mark, thank you very much. Stay here. Hi, my name is Bryna Helfer. I'm the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Public Engagement and we just wanna, Mark, I guess I we just want to go back. We've been getting some questions about the elements, and I was wondering if you might just spend a little bit of time talking about your vision for the elements and what goes into some of these elements. If you could, that would be awesome, thanks.

MARK: Sure. So, in urban automation oftentimes when people talk about automated vehicles they talk about it in a singular, linear sense. We actually think that urban automation goes beyond just the urban, beyond the automated vehicle. The moving of goods through automation, the moving of people through automation, and how it interacts with the sharing economy, how it interacts with connected vehicles, and how it interacts with this sensor-based infrastructure that's either in the city already or is being developed by the city. So, the important part about the technology elements is that we're not looking for just another connected vehicle pilot. We're not looking for just an automation pilot. We're looking for how these different technologies work together. The innovative approaches, if you go through them, we have a very lengthy description in the notice of funding opportunity as to what they all mean. But if you look at the connected and involved citizens, it's important that we get through urban delivery and logistics, etc. Finally, the Smart City elements, the smart land use, etc., are very, are described. And those are key elements.

Wanted to introduce Secretary of Transportation now who will talk a little bit about the Smart City Challenge.

SECRETARY FOXX: Hi Everyone, thank you, Mark, and thank all of you so much for joining today's webcast. As you know, yesterday we launched our Smart City Challenge targeting mid-size cities. This is an opportunity for mayors and city leaders to define what it means to be a smart city when it comes to transportation. We're asking cities to submit proposals by February 4th, and our goal will be to narrow the proposals down to five finalists by May and announce the winner in June; the winner will then receive up to forty million dollars to implement their proposal. That's not all. As Mark has probably alluded to already, our partner in this effort, Vulcan, is offering an additional ten million dollars to the winning city. And our hope is that cities will see this as an opportunity to partner with firms like Vulcan, and other innovators that can help them re-imagine their transportation systems.

Let me just talk some about why we are doing this. First of all, we don't have a top-down transportation system in the U.S., we have a bottom-up system, and while we are grateful that Congress passed a five-year transportation bill last week, our national vision for transportation is still in some ways stuck in the 20th century when it comes to thinking about technology, innovation, and the kind of inputs that mayors and local officials think about all the time when it comes to how to integrate transportation and quality of life and, of course, protecting our environment and so many other issues. So, our department is working hard on the national level to create policies and programs and practices that help make it easier for local and state decision-makers to do these things. We're trying to reposition government so we can help you solve problems at the local level. We also want to increase our ability to rapidly absorb technology in the transportation space so we can do things that previous generations could only imagine. So, we're imagining things like connected and autonomous vehicles that practically eliminate crashes. And we're imagining this technology interacting with wired infrastructure to eliminate traffic jams as well, but we're not only imagining it happening, we're making it happen. We're moving quickly to require all new cars to be equipped with vehicle-to-vehicle technology. And, as part of this effort, we also launched a pilot program to demonstrate connected vehicles in three US cities, including New York. We're updating our policy position on autonomous vehicles and we're working to integrate unmanned aircraft into the National Airspace. We even have hired our first data chief data officer. So, we've pushed as hard as we can and will keep pushing at the national level, and now we're hoping to incentivize you at the local level to work just as hard. And, ultimately, we know that the best laboratory we have for emerging innovation and technology is where it is most needed, which is in our cities.

Another forward-looking thing we did was to look at our transportation system over the next 30 years, and this bears directly on all of you on the call. Our report "Beyond Traffic" tells us that we're gonna add seventy million more people to our population over the next thirty years, and it's also telling us that our cities will absorb most of this growth. This is part of the reason it's been said that the 20th century will not be dominated by countries, but it will, in fact, be dominated by the rise of cities and the rise of urbanization in regionalism. Along these lines, the entire world is now having a conversation about smart cities which is really a conversation about what our cities should look like in the future, and now our cities will need to show us. In this challenge, all of you will help define what a smart city is. So, rather than be prescriptive, we want you to be bold. We're asking you to develop your own unique vision, your own unique partnerships, your own unique blueprints, for building the city of the future, and we're putting the ball in your court in giving you the opportunity to demonstrate to the world what a fully integrated, forward-looking transportation network looks like. I want to say this because I know that many of you have been working on your community's vision statements and plans and land use strategies and all sorts of things. This challenge is an opportunity to bring all that together and to make progress. So to everyone joining us for this, I want to assure you that this is not only the beginning of our outreach process; we will continue making outreach happen over the next several weeks. In fact, tomorrow we'll host a smart city forum. Actually, I'm sorry, December fifteenth we will host a smart city forum, and we encourage folks to join us in person, but will also have a virtual option available as well. As I say, we'll have more webinars in the coming weeks. So, I'm looking forward to seeing the proposals that come forth. I'm also looking forward to working with you, all of you to push the boundaries of what is possible. And, with that, I'll turn it back to my team to give you more details and answer any questions you have and with that, thank you very much. It's been great to be with you.

KEVIN: Thank you Secretary Foxx and thank you, Mark Dowd. As the secretary just mentioned, I want to remind you that you can sign up online for the December 15th in-person Smart City forum here at USDOT. He did mention that there will be an online option also. Please go to www.transportation.gov/smartcity [9] that's www.transportation.gov/smartcity [9]. Ladies and gentlemen, thank you very much again for joining us today.

Video: #SmartCityPitch: Columbus (2:35)

ON SCREEN TEXT: In Columbus, we've built an unprecedented culture of collaboration. We've knocked down silos, and built up partnerships to become the Midwest's fastest-growing city. #1 in job growth #1 in population growth. Our culture of collaboration is the Columbus way. It is how $50 million becomes $140 million. We will set the pace for smart city transformation. We will connect hard-working people to jobs. We will lift a low-income community out of poverty. Give students of all ages unprecedented access to education. Give more expectant mothers access to prenatal care, and get more children to Pre-K. Through collaboration, we get things done. By sharing data, and leveraging advanced analytics, we will clear congestion and improve safety like never before. We will demonstrate how a city can leap ahead. You see, we know how to lead (fastest growing city for startup activity in 2015), to collaborate (#1 metro for job growth in the Midwest), to set a bold vision (lead the country in smart mobility), and best of all we know how to deliver results. So, let's transform Columbus. Let's build a connected, cutting edge, sustainable, smart city. Smart Columbus will move America forward. We're ready. All of us. #smartcolumbus

The winner, announced in June 2016, was Columbus, Ohio. I think you’ll agree that their winning pitch (see above) exhibited an impressive use of multimedia.

Take a look at these links to see what's happened since the award was made in June 2016:

- The USDOT published a report [11] summarizing the lessons learned thus far.

- The city of Columbus is maintaining a list of the Smart City projects [12] which are planned or underway.

- Learn how Columbus turned the $50 million award into $500 million [13] by leveraging private investment (also check out the video at the top of the page to see some of their innovative ideas).

1.4 Getting to Know Each Other

One of my goals for this course is to promote meaningful interactions between all of us as we cover topics in GIS-T over the next 10 weeks and to lay the framework for building relationships which will extend beyond the end of the course. Throughout the course, you will have the opportunity to get to know your classmates and me a little better. As a first step, you will create a video autobiography so we can begin to get to know you. In later lessons, you will spend time in one-on-one video chats with your classmates getting to know each other better.

1.5 Webinar for Next Week

Speaker

Our next webinar will be with Mr. Michael Ratcliffe. Michael is Assistant Division Chief for Geographic Standards, Criteria, Research, and Quality in the Census Bureau’s Geography Division, where he is responsible for geographic area concepts and criteria, address and geospatial data quality, and research activities. During his tenure at the Census Bureau, he has worked in both the Geography and Population Divisions, on a variety of geographic area programs, including urban and rural areas, metropolitan and micropolitan statistical areas, and other statistical geographic areas, and has led staff engaged in product development and dissemination. In addition to his work at the Census Bureau, he is an adjunct professor at George Washington University, where he teaches Population Geography. Prior to that appointment, he was an adjunct instructor at the University of Maryland-Baltimore County. Mr. Ratcliffe holds degrees in geography from the University of Oxford and the University of Maryland.

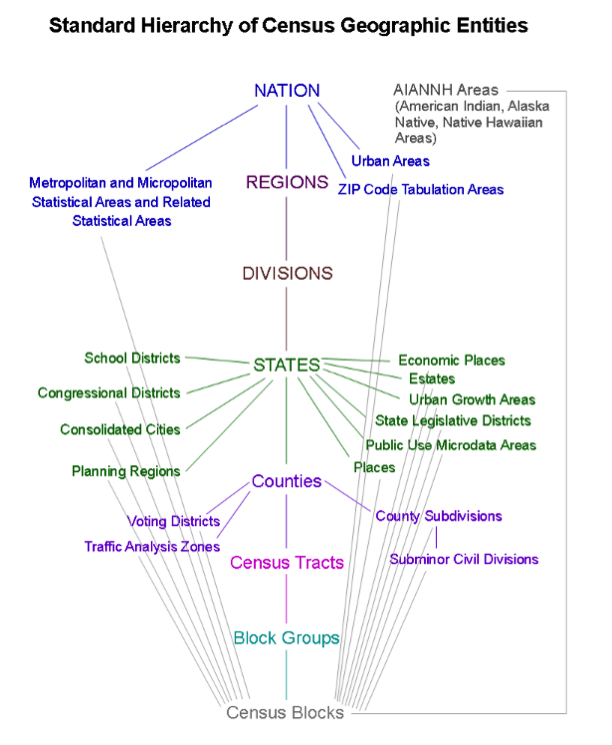

Geographic Areas Used by the Census Bureau

The Census Bureau defines many different geographic areas which can be used to organize and aggregate data. The areas the Census Bureau uses can be divided into those which are legally defined and those which are not. The Census Bureau refers to non-legally defined areas as statistical areas.

Nation

Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas and Related Statistical Areas

Urban Areas

ZIP Code Tabulation Areas

Regions

Divisions

States

School Districts

Congressional Districts

Consolidated Cities

Planning Regions

Economic Places

Estates

Urban Growth Areas

State Legislative Districts

Public Use Microdata Areas

Places

Counties

Voting Districts

Traffic Analysis Zones

County Subdivisions

Subminor Civil Divisions

Census Tracts

Block Groups

Census Blocks

AIANNH Areas (American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian Areas)

Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas and Related Statistical Areas

Urban Areas

ZIP Code Tabulation Areas

School Districts

Congressional Districts

Consolidated Cities

Planning Regions

Economic Places

Estates

Urban Growth Areas

State Legislative Districts

Public Use Microdata Areas

Places

Voting Districts

Traffic Analysis Zones

County Subdivisions

Subminor Civil Divisions

1.5 Summary of Lesson 1

In this lesson you:

- briefly examined the important role GIS plays in the field of transportation and learned about the manner in which GIS-T is evolving in the 21st century. \

- learned something about transportation modes and the concepts of mode competition, mode shift, and containerization.

- spent some time learning about the role of the USDOT in the transportation industry. .

- aquainted yourself with the speaker and general topics for next week's webinar.

- took the first step in getting to know each other by creating a video autobiography which will serve to introduce you to the rest of the class.

Questions and Comments

If there is anything in the Lesson 1 materials about which you would like to ask a question or provide a comment, submit a posting to the Lesson 1 Questions and Comments discussion. Also, review others' postings to this discussion and respond if you have something to offer or if you are able to help.

Lesson 2: Roadway Centerline Data

Learning Outcomes

What will we learn?

By the end of Lesson 2, you should be able to:

- compare and contrast different sources of roadway data which are available;

- compare the ways Google and OSM enlist the help of volunteers to improve their roadway data;

- describe the characteristics of the TIGER/Line shapefiles and OSM data;

- discuss the use of Census data for transportation planning;

- explain the purpose of Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) and describe how it impacts transportation projects;

- list some details about your classmates based on your review of their video autobiographies.

2.1 Roadway Data Sources Used in GIS-T

Roadway data are fundamental to GIS-T and many of the most important transportation modes (e.g. highway, transit, bike). Many GIS functions and analyses rely on it including geocoding and network analysis, both of which we’ll take a close look at in the next few lessons. Roadway data also play an important role in mapping and visualization for many GIS applications.

There are a number of commercial and public sources of street data and services which are available. Some are public and freely available, and others are commercial. In this lesson, we’ll take a look at some of the most widely used sources of street data.

Public Sources

TIGER Data

TIGER is a data source produced and published by the U.S. Census Bureau. These data include street data which can be used to perform geocoding or to produce a street network. TIGER data were used as a “seed” for many of the other roadway data sources, both public and commercial. We will take a closer look at TIGER data later in this section.

OpenStreetMap (OSM)

OSM is a rapidly growing Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) project which got its start in 2004 and is sponsored by the OpenStreetMap Foundation. For U.S. roads, OSM initially used TIGER Line files but many updates have since been made based on input from its volunteer community which is now over a million strong. In some parts of the world, OSM data are as good, or nearly as good, as its commercial counterparts.

Agency-Generated

State-level transportation agencies have long maintained road centerline networks as well as additional networks for other modes. They have been improved greatly in accuracy and precision, and agencies are increasingly adding local and private roads and associated data. Much of this latter impetus is due to increased federal requirements for data collection and reporting. In most cases, these networks are the most complete and accurate product for network features and associated attributes for any given state.

Transportation for the Nation (TFTN)

TFTN is an evolving governmental initiative from the National States Geographic Information Council (NSGIC) and USDOT that originated in 2008. TFTN will initially be a road centerline dataset that may replace overlapping federal efforts and products. A set of centerline datasets has been created as part of state DOT submittal requirements for FHWA’s Highway Performance Monitoring System (HPMS). The next step is to try and join these across state lines.

Commercial Sources

TomTom / Tele Atlas

Tele Atlas was founded in 1984 and was acquired by TomTom in 2008. Tele Atlas data was primarily collected from its own mapping vans. The company’s road products are decreasing in importance and usage.

Nokia / NAVTEQ / HERE

Founded in 1985 and acquired by Nokia in 1991, NAVTEQ (now renamed HERE) operates independently and partners with third-party agencies and companies to provide its networks and services for portable GPS devices made by Garmin and others, and Web-based applications including Yahoo! Maps, Bing Maps, Nokia Maps, and MapQuest.

ESRI StreetMap and StreetMap Premium

ESRI does not produce road data directly but instead acquires it from HERE, TomTom, and others and repackages it. ESRI StreetMap covers North America and is part of Data and Maps which is included with ArcGIS. StreetMap premium has more current data than StreetMap and also has coverage for Europe.

Google has become a major provider of mapping services. Google doesn’t make its street data available directly but instead uses it to provide services. These services are provided through products such as Google Maps, Google Earth, and various APIs. In 2008, Google released a tool called Google Map Maker to encourage individuals to submit or correct feature information. This is similar in concept to the manner in which OSM derives much of its data. Google retired Map Maker in 2017 in favor of its "Local Guides [15]" program. As a "Local Guide," you can contribute reviews of businesses or places, upload photos and suggest a new place. Recently, they also began to add capabilities to allow users to report issues with roadway geometry and missing roads. Local Guide contributions are all made directly in the Google Maps interface. Take a look at these comparisons between OSM and Google in regards to the services [16] they provide and their user contributions [17] programs. One should note these comparisons are published on the OSM Wiki site so they may be a bit biased.

Also, check out this map comparison tool [18] made available by Geofabrik, an organization who promotes OSM and provides a portal for downloading OSM data extracts. Select an area you are familiar with, and compare the OSM map, the Google map, and the HERE map.

2.2 Exploring TIGER and OSM Data

In this section, we'll take a closer look at two of the most extensive sources of publicly available roadway data: TIGER and OSM.

The TIGER database was first created in preparation for the 1990 decennial census. In creating TIGER, not only did the Census Bureau produce the first nationwide map of roadways, it also incorporated topographical context which defined the relationship between road features as indicated in its name: Topologically Integrated Geographic Encoding and Referencing database.

In addition to the TIGER spatial database, the Census Bureau also created a Master Address File (MAF) which is a database of all known living quarters in the U.S. The MAF contains about 300,000 addresses which are identified as location addresses, mailing addresses or both. In addition, the MAF contains a record for each living unit which can correspond to a separate structure or a residence within a shared structure. There are about 200,000 living units in the MAF some of which have multiple associated addresses. Following the 2000 decennial census, the Census Bureau decided to merge the two databases into a single database known as the MAF/TIGER Database (MTdb).

The Census Bureau is planning a 3-part informational series on TIGER to commemorate its 25th anniversary. Part 1 will examine the history of TIGER, Part 2 will address efforts to improve its accuracy, and Part 3 will address the tools which provide access to the data. To date, only Part 1 of the series [19] has been made available. Spend a few minutes looking through the document to learn a little about TIGER’s history.

The TIGER data is available in a number of formats [20] including Shapefiles, geodatabases, and KML files. The Census Bureau also provides a tool called TIGERweb [21] which allow online viewing and the ability to incorporate TIGER data directly in GIS applications via web services including an OGC standard Web Mapping Service (WMS). For the exercises in this and the upcoming lesson, we will be working with the TIGER/Line shapefiles [22].

The Tiger/Line shapefiles are available for multiple years. Each year, the Census Bureau provides an updated set of Tiger/Line shapefiles in addition to associated technical documentation. The technical documentation for the 2017 Tiger/Line shapefiles can be found here [23]. It is over 120 pages long and serves as an excellent reference for the Tiger/Line Shapefiles.

With more than 3 million registered users, the OSM project has a huge community behind it. Consequently, there is plenty of documentation available for learning about the project and becoming a member of the community. A few good resources for learning about OSM are the Open Street Map Wiki [24]and the guides on LearnOSM.org [25].

OSM data is natively available in a unique file format (i.e., .osm files). However, many of the sites which provide access to OSM data serve it up in commonly used formats like shapefiles. For example, take a look at Geofabrik’s OSM data download page [26]. Also, take a look at the first few sections of the OSM Data Guide [27] which describe the .osm file format and some options for acquiring OSM data.

We often talk about spatial data in terms of points, lines, polygons, and attributes. OSM, however, uses the terms nodes, ways, relations and tags. In order to develop some understanding of these terms, take a look the descriptions of OSM data’s elements [28]on the OSM Wiki site.

2.3 Getting to Know a Transportation Organization

In preparation for this week's webinar, you learned about the geographic areas the Census Bureau uses to tabulate and disseminate data. This week, you’ll explore the Census Bureau in greater detail. The Census Bureau is part of the U.S. Department of Commerce. The mission of the Census Bureau is to “serve as the leading source of quality data about the nation's people and economy.” To fulfill its data gathering objectives, the Bureau conducts both decennial censuses and a continuous survey known as the American Community Survey (ACS). The ACS was born in 2005 out of a need for more up-to-date information than the decennial census provided. Data from both the decennial census and the ACS are made available in a variety of ways, one of the most popular of which is the via the American FactFinder site [29].

Take a look through the American Community Survey Information Guide [30] which the Census Bureau updated in December 2017.

Data collected by the Census Bureau serve some critical functions. These data are used to:

- determine the number of seats each state has in the house of representatives;

- distribute over 400 billion dollars in federal funding annually;

- make planning decisions about community services.

Geography and GIS are very important to the Census Bureau.

Watch this brief presentation on the Maps of the US Census Bureau [31] (5 minutes) by Atri Kalluri, Assistant Division Chief of the US Census Bureau.

Census data have long been applied to transportation planning and research. Today, there are a number of emerging sources of data which serve to compete with or complement the role of the census data in these fields. Read this 2017 paper [32] by Gregory D. Erhardt (University of Kentucky) and Adam Dennett (Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis, University College, London) which examines this topic.

Census Transportation Planning Products Program

The Census Transportation Planning Products Program (CTPP) [33] is an initiative led by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO). AASHTO is an organization we’ll take a closer look at in an upcoming lesson. The CTPP provides special tabulations of Census data which are of particular interest to transportation planners. These datasets provide insight into how people commute and which modes of transportation they use. They are often used to validate travel demand models which themselves are used to make decisions on what types of transportation projects are needed to support regional needs, including those related to economic growth, public health, transit needs, and highway safety issues (for a quick overview of the Four Step Model (FSM) which commonly used in travel demand modeling, see this 2007 article by Michael McNally at the University of California, Irvine [34]).

To facilitate the use of the CTPP data, AASHTO created a web-based application [35]to examine travel flows. The CTPP even has a YouTube channel devoted to teaching people how to use the software (although the quality of the videos is less than stellar). Take a look at the YouTube video below (5 minutes) which shows how to generate some basic county to county commuter flow data. The CTPP data analysis tool also has the ability to display results in a variety of formats including thematic maps.

Video: CTPP Software - select geography by list and map (5:29)

Click for a transcript of CTPP Software.

Hi, this is Penelope Weinberger. I'm the Census Transportation Planning Products Program Manager at ASHTO, recording some brief tutorials on the CTPP data access software. The tutorial you're about to watch is on selecting geography. There are two parts to the CTPP, residence and workplace, and there are two ways to select geography, by list and by map. We're going to look at both of those.

The CTPP data access software is a powerful tool to access the nearly 350 gigs of data provided by the Census Bureau. The dataset consists of almost 200 residence-based tables, 115 workplace-based tables, and 39 flow tables from (inaudible), 325,000 geographies. The data is derived from the American Community Survey Microdata record based on the 2006-2010 ACS. Looking at here is the home screen for the CTPP data access software. I'm not going to select a table. I'm going to go straight to selecting geography. As you can see, I have Residence geography by the red box and Workplace geography by the blue box. The default geography for all CTPP tables is States. We're going to change that right now. I'm going to click on Residence, and the software is going to open up and show me. On the left-hand side of the screen, I'm looking at my select level. State is what's highlighted, and States are what are selected. I have 52 states selected, that includes DC and Puerto Rico. Like all good GISs, I'm going to have to clear my selection if I don't want it in the table. So, the first thing I do is hit clear full selection. Then, I have to decide what level of geography I'm interested in. I'm interested in counties. There are 3,221 counties in the US, and I have none of them selected. So, first, I pick my level, and then it's gonna give me a list starting in Alabama. Well, I don't want to scroll all the way down from Alabama to Maryland, so I'm gonna search for Maryland, instead. I put my cursor in the search box, and I type Maryland, and then click on the search tool and also hit enter.

In the CTPP, you can have mixed levels of geography. This tutorial is just going to look at counties. Now, I have my 24 counties in Maryland. I'm gonna choose to select all of them, and I click the Select All button on the right-hand side, check marks by each one. Pretty Nifty! Now, I want to pick my workplace geography. I'm actually gonna pick the same geography. I do want you to take note that where it said all states before, now it says new set. If I want to save this set of just Maryland counties or any geography I create, we'll have to sign in, but I'm not going to do that today. Now, I'm just gonna click on workplace, and instead of picking by list, I'm gonna pick by map. So, instead of using the selection list tab, I'm going to use the selection map tab. Click on that, and it shows me a cool map of the United States. Of course, I have all my states selected since that's my default. So, I'm going to clear the selection. On the map, you do that over on the right-hand side with the little garbage can. (...they go!) Now, I pick my level. I want counties again. I want place over counties.

Now, I could do this a number of ways. I could zoom in with my tool just to where I happen to know Maryland is, and I could pick the counties one by one. That could be a little bit tedious. So, instead, I'm going to use this cool Zoom To and Select tool. Place overstate is what I want cause that is the parent. Down here, it says automatically highlight any place over County. I click that on, I type in Maryland. Hit Enter. It's loading up my Maryland counties. Now, look, 24 places over counties. It's good those two numbers match. Do I want to add all highlighted counties to my selection? I do. So, I click that, and there they all are.

Now, let's see if I can look at a table with my county residences and my county workplaces. Show CTPP tables. Of course, I want a flow table since I've got two geographies selected. Workers, let's just look at total workers. Now, one thing that's a little odd about this table, is that the residence and the workplace are both on the [INAUDIBLE], so I'm going to move one of those so that I have a matrix. I like my data as is. I'm going to grab my Residence by the textured box to the left of the word, and I'm going to drag it up till it is over output with that up-pointing arrow. I'm going to drop it. Now my output is going to nest on the Residences. It's a great-looking matrix. I have 25,000 workers that live in Allegheny and that work in Allegheny County. 153,000 live in Anne Arundel and work in Anne Arundel. It should go right down that way, the biggest numbers now in the matrix. Sure looks like it does.

Another interesting use of the commuter flow data can be seen in an application created by Mark Evans. Mark used the Google Maps API to create a GIS application called Commuter Flows [37] which facilitates the visualization of census tract level commuter flows derived from the ACS data.

2.4 Getting to Know Each Other

This week, you will get to know a little about each other by reviewing the video autobiographies posted by your classmates in Lesson 1. You’ll also have a one-on-one chat with one of your classmates as per the schedule you were provided at the end of Week 1. The discussion should be at least 30 minutes in length. If it’s the first time you’ve chatted with each other, spend the majority of time getting to know each other. Otherwise, focus on discussing the lesson content.

2.5 Webinar for Next Week

Speaker

Our speaker will be Dr. Ira Beckerman. Ira has been the Cultural Resources Section Chief for the Bureau of Design at PennDOT since 1998. Trained as an archaeologist (Ph.D. Anthropology, Penn State, 1986), he has worked as a field archaeologist in Mexico, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania. His 22 years of transportation experience is split between PennDOT and (previously) the Maryland State Highway Administration. Dr. Beckerman’s research interests include archaeological predictive modeling, pre-contact Eastern North America, and GIS. He is a member of the Society for American Archaeology, Register of Professional Archaeologists, and the Transportation Research Board’s Archaeology and Historic Preservation Committee, and has served on panels for TRB and the American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO). Dr. Beckerman was a 2001 recipient of the PennDOT Star of Excellence. His group also recently led an effort to develop a predictive model for archaeological sites which serves as a valuable tool for screening projects early in the planning process.

Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA)

The National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) was passed into law in 1966. The purpose of the law is to protect historic and archaeological sites of significance. One outcome of the NHPA was the creation of the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP), which is a list of districts, sites, and structures deemed worthy of protection. There are more than 1 million properties currently on the list and about 30,000 additional properties are added annually. Section 106 of the NHPA specifically requires historical and archaeological sites to be assessed for impact as part of any federally funded project.

To gain a better understanding of the Section 106 process, take a look at A Citizen’s Guide to Section 106 Review [38], a brief overview put together by the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation. Also, watch the following video which describes the process which agencies need to follow to comply with Section 106 of NHPA.

Video: Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (7:52)

There are several areas of environmental law that local public agencies, or LPAs, might encounter on a Federal-aid project. These areas address a project's effects on: the natural environment; things like air and water quality, wetlands, wildlife or endangered species, the social environment; things that affect our quality of life, like the displacement of homes or businesses or community cohesion impacts, particularly as they relate to minority and low-income populations, historic sites, and parks and recreation areas. The National Environmental Policy Act, known as NEPA, provides a framework for environmental analyses, reviews, and series of discussions known as consultations. NEPA's process "umbrella" covers a project's compliance with all pertinent Federal environmental laws. While NEPA provides a coordinated environmental review process, the related environmental law specifies what an agency must do to comply with its particular requirements, which can vary widely. One such law, Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, requires Federal agencies to consider the effects of their projects on historic properties. A historic property is any prehistoric or historic district, site, building, structure, or object that is included in or eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places. The Advisory Council on Historic Preservation and the State Historic Preservation Officers, or SHPOs, administer the federal or state historic preservation program. The National Historic Preservation Act does not mandate preservation of historic properties; however, if your project receives Federal-aid funding, your agency must participate in a consultation process that considers the effects of your project on those properties. Depending on the project, consulting parties may include: the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, your SHPO, the Tribal Historic Preservation officer, Federally recognized Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian Organizations, local governments, and the public. Let's take a look at the consultation process and the responsibilities of agencies in complying with the National Historic Preservation Act. While the consultation process is somewhat iterative, there are four basic steps: initiate consultation, identify and evaluate historic properties, assess effects, and resolve effects To initiate consultation, a local agency typically sends a letter of correspondence to either the SHPO or the State’s department of transportation, or State DOT, identifying the project, the project location, and who is involved. And if known, an agency will also identify any historic properties in the project area. In order to properly identify and evaluate any potential archeological and historic sites, an agency needs to utilize a qualified employee or hire a consultant. The evaluator will begin by performing file and literature searches to determine if the property is on or potentially eligible for the National Registry of Historic Places. The resulting report summarizes the site's setting and historical context, project information, including maps, and any cultural resources that were identified. If there are no historic properties in the project area or no adverse effects are likely to occur to ones that are present, an agency will issue a letter with its findings, which completes the consultation process. On the other hand, if adverse effects are likely to occur, an assessment must be made. An adverse effect occurs when an element of a historic property is altered in a manner that diminishes the integrity of the property’s location, design, setting, materials, workmanship or association. For example, noise or visual blight can be considered an adverse effect. The public and the consulting members of the project team can help determine any adverse effects resulting from the project. Once potential adverse effects are identified, an agency needs to evaluate possible alternatives or modifications that would help resolve the effects by avoiding, minimizing, or mitigating them. For example, the alignment of a road might be altered to avoid affecting a historic property, or a commemorative publication or plaque might be erected. The process concludes when the agency finalizes a memorandum of agreement between consulting agencies. To illustrate the process, let’s consider a drainage and road improvement project in a town we’ll call Old Towne, which was established in the early 19th Century. To initiate the consultation process, the project manager sends a letter to the SHPO describing the project and providing a map of the project area. The city of Old Towne hires a consultant with recent experience developing similar studies for the State DOT. During the course of her literature review, she discovers evidence of an early 19th-Century tavern at the corner of 1st and Main. During a site visit, she confirms that there is no longer any evidence of the tavern from the ground's surface. The project team then conducts a subsurface investigation of the area and finds the foundation of the tavern and an outhouse. Further excavation indicates that the site might yield important information about the lifestyle of Old Towne’s earliest residents. Unfortunately, given its proximity to the street, the drainage and road improvement work would destroy the archeological site. To resolve the adverse effects, the project team consults with the SHPO, the local historical society, the State DOT, and the Federal Highway Administration’s division office. After the artifacts are analyzed and a report is prepared, the team agrees to erect an interpretive sign describing what was found and to give any recovered artifacts to the county museum. With everyone satisfied with this arrangement, the project team concludes the consultation process by writing a memorandum of agreement. As we have seen, as a sponsor of a federally-aided transportation project, your agency may be required to conduct studies and coordinate with other parties. The necessary activities and degree of your involvement depend on the nature of your project and your State DOT’s practices. Your State DOT can help you navigate the requirements and develop approaches that adequately evaluate and address your project’s effect on historic properties.

Cultural Resources GIS

Many states have developed GIS-based systems to help state agencies and other interested parties identify historic properties and known archaeological sites and assess their proximity to planned projects. Spend some time exploring Pennsylvania’s Cultural Resources Geographic Information System (CRGIS) [40]. CRGIS was created and maintained through a collaborative partnership between the Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission (PHMC) and PennDOT. (note: CRGIS requires that pop-ups are allowed ... so you'll have to enable them in your browser either in general or for this site specifically. You can disable them again when you're done exploring CRGIS. Instructions for adjusting pop-up settings in Internet Explorer/Edge and Chrome are included in the "Getting Started" link in the upper right portion of the CRGIS website.)

Archaeological Predictive Modeling

A number of efforts have been undertaken in recent years to use predictive modeling to identify locations which are likely archaeological sites. In Pennsylvania, FHWA, PennDOT, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC) and URS Corporation partnered to create such a predictive model which is described in brief here [41]. The model uses data from known archaeological sites together with spatial algorithms to rank areas based on their likelihood of having artifacts. These data are then used in evaluating potential projects and alternatives.

2.6 Summary of Lesson 2

In this lesson, we discussed the importance of roadway centerline data to GIS and explored some of the public and commercial sources for this data. In particular, we took a close look at the Census Bureau’s TIGER data in addition to the data available via Open Street Map (OSM).

Our transportation organization of the week was the Census Bureau. We spent some time learning about the American Community Survey and the role that Census data plays in transportation planning.

In preparation for next week's webinar, we reviewed the role of Section 106 of NHPA in transportation projects and explored a cultural resources GIS application.

Finally, you had the opportunity to learn a little bit about your classmates by reviewing their video autobiographies and by having your first one-on-one conversation.

Questions and Comments

If there is anything in the Lesson 2 materials about which you would like to ask a question or provide a comment, submit a posting to the Lesson 2 Questions and Comments discussion. Also, review others’ postings to this discussion and respond if you have something to offer or if you are able to help.

Lesson 3: Geocoding and Conflation

Learning Outcomes

What will we learn?

By the end of Lesson 3, you should be able to:

- describe the process of geocoding and discuss some of the more common types of geocoding which are used;

- discuss the purpose and characteristics of an address locator;

- create an address locator using TIGER/Line shapefiles and use it to geocode a list of addresses;

- discuss conflation as it applies to GIS-T and use some of the tools in ArcMap to assist in conflation activities;

- define the process of conflation as it applies to roadway data and identify some situations where conflation would be performed;

- list the key functions of an MPO and RPO;

- describe the transportation plans which are created and maintained by MPOs, RPOs, and state Departments of Transportation (DOT).

3.1 Geocoding and Conflation

Geocoding

Geocoding is the process of taking the description of a specific location and converting it into a set of coordinates or a point feature which can then be displayed on a map or used in some type of spatial analysis. A variety of location description types can be geocoded including addresses and place names. There are a number of different approaches which can be used for geocoding, but at a high level they all follow the same process:

- Descriptions of the locations to be geocoded are compiled into a standard format.

- The location descriptions are compared to a reference dataset.

- Candidate locations are established and scored according to a set of rules.

- If the score for a candidate location exceeds a threshold value, it is declared a match.

- If no candidate location score exceeds the established threshold, the location of interest is flagged as unmatched.

- If two or more candidate locations share the same score and that score exceeds the threshold value, a tie is declared.

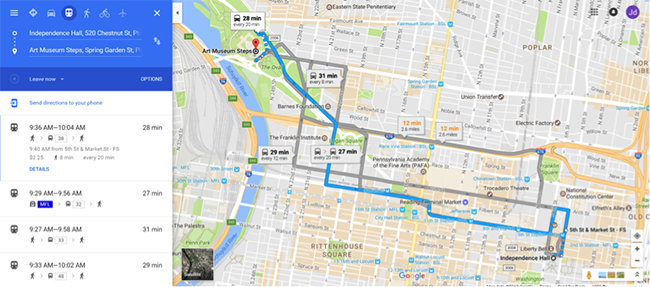

Geocoding is a widely used geospatial technique that has applications across many industries. It is often a prerequisite process to performing some type of network analysis such as routing. There are a variety of distinct processes which can be used for geocoding. The primary differences lie in the type of reference data which is used. The most common type of geocoding uses roadway centerline data where each street segment has address range attributes for each side of the street. Most online geocoding services, including Google Maps, Yahoo Maps, and MapQuest, rely almost exclusively on this type of geocoding. Other types of geocoding use parcel boundary data or address point data. You’ll read more about the different types of geocoding in Assignment 3-1.

There are many geocoding services which are available, some of which are free and some of which are subscription-based. The free services generally limit the number of locations you can process at one time. Given a suitable reference dataset, it is also possible to create your own geocoding service. You’ll have an opportunity to do just that in Assignment 3-2.

ArcGIS Address Locators

The first step to geocoding in ArcGIS is selecting an address locator which will be used. The address locator defines the reference dataset and the rules which will be used by the geocoding engine in identifying candidates and matches for the location descriptions (typically addresses) you are trying to locate. You can use an existing address locator, which typically requires a subscription, or you can create your own. To create your own address locator, you need to have access to a suitable set of reference data. There are many potential reference datasets available including those which are created by state or county governments. One good source of reference data for geocoding is the TIGER/Line shapefiles we examined in Lesson 2.

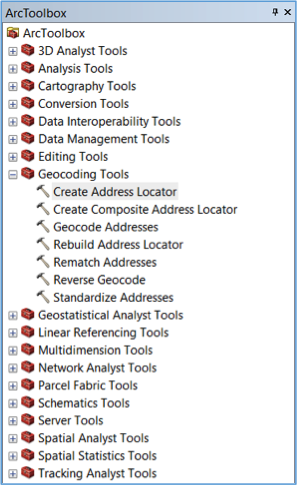

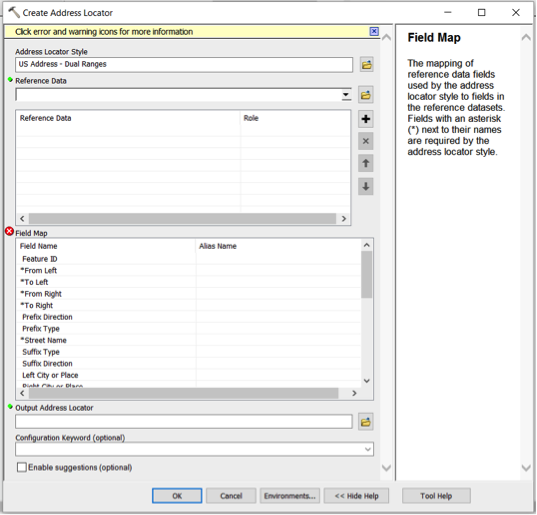

To create an address locator, use the “Create Address Locator” tool in ArcToolbox (see Figure 3.1).

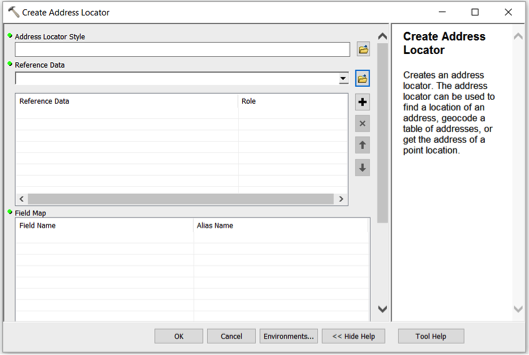

When you launch the tool, you are presented with the Address Locator dialog (see Figure 3.2).

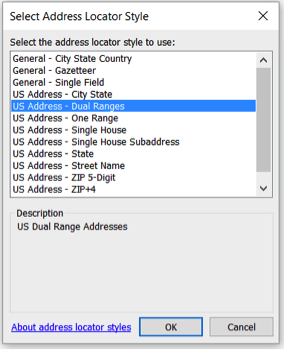

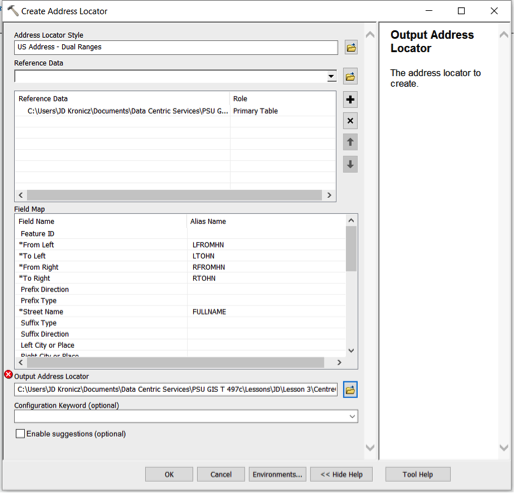

The first step in creating an address locator is selecting a locator style. The locator style which is most appropriate depends on the reference data you’re planning to use in addition to the format of the locations you’re trying to geocode. A commonly used address locator style is the U.S. Addresses – Dual Ranges (see Figure 3.3).

Once the locator style has been selected, the Field Map list in the bottom portion of the Address Locator dialog is automatically populated (see Figure 3.4). Fields with an asterisk are required by the locator style, and fields without an asterisk are optional. Once you have loaded a reference dataset, you can map these fields to the corresponding fields in the reference data.

The second step in creating an address locator is defining the reference dataset or datasets which will be used. As mentioned above, there are many reference data sources which can be used. For example, you can use a linear feature class based on roadway centerlines such as the “Address Range-Feature Shapefile” TIGER/Line shapefiles we reviewed in Lesson 2. Alternatively, you could use a polygon feature class based on parcel boundaries or zip code boundaries. Yet another option would be to use a point feature class based on address points.

Once you have selected the reference data, you can map the fields associated with the address locator style you have selected with the corresponding fields in the reference data (see Figure 3.5).

The final step is to save the address locator to a location you select. While you can store the locator in either a geodatabase or a file folder, ESRI recommends storing an address locator in a file folder for better performance.

Here is a link to an ESRI webpage where you can download a white paper [42] which tells you everything you’d ever want to know about address locators in ArcGIS.

Geocoding a List of Addresses (or other location descriptions)

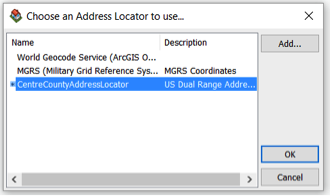

To geocode a list of addresses, you should first add the table of addresses data to your map document in ArcGIS. The addresses to be geocoded can be prepared in any number of file formats including xlsx, xls, dbf, csv, and txt. Once the table of addresses has been added, you can right-click on the newly added table and select “Geocode Addresses” from the resulting context menu. At this point, you’ll be asked to select an address locator (see Figure 3.6).

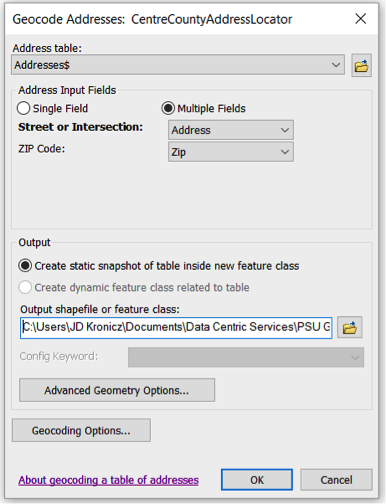

If the address locator you wish to use is not in the list, you can add it. Once you select an address locator and click “ok,” you will be presented with the “Geocode Addresses” dialog (see Figure 3.7).

In the top portion of the dialog, you can map the fields in the input table to the corresponding fields in the address locator, if it isn’t done automatically, and define the location and name of the shapefile or feature class where the results of the geocoding process should be stored. You can also configure some parameters for the address locator by clicking the “Geocoding Options” button. The “Geocoding Options” dialog is then displayed (see Figure 3.8).

In the top portion of the dialog, you can exercise some control over how matching is performed. The spelling sensitivity level controls the extent to which misspellings will still be considered a match. The lower the score, the more tolerant the geocoding engine is for misspelled words. The minimum candidate score sets the threshold score for identifying candidates. The lower this score, the more candidates an address could have. Finally, the minimum match score establishes the threshold score for declaring a match for the address. Lowering the minimum match score will generally increase the match rate but will also tend to result in a higher rate of false positives.

The dialog can also be used to set other parameters for the geocoding engine such as offset positions for geocoded point features and some output data elements which can optionally be included as attributes in the resultant shapefile or feature class.

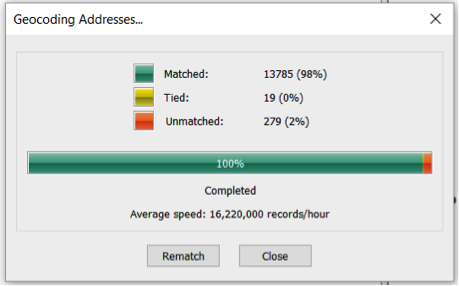

Once the geocoding options have been defined, the geocoding process can be initiated by clicking “Ok” on the “Geocode Addresses” dialog (see Figure 3.7). When the geocoding process is complete, a summary of the geocoding results is presented (see Figure 3.9).

This summary shows the number of addresses which had candidates above the minimum match score (i.e., matches), the number of addresses which had multiple candidates which were above the minimum match score and had the same score (i.e., ties) and the number of addresses which did not produce any candidates above the minimum candidate score (i.e., unmatched).

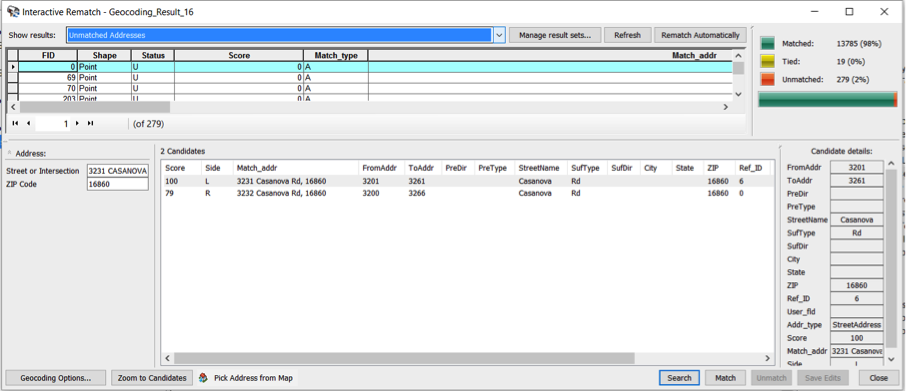

From the results summary screen, a manual rematch process can be initiated by clicking the “Rematch” button. This brings up the “Interactive Rematch” screen (see Figure 3.10).

On this screen, unmatched addresses, ties, and matched addresses can be reviewed. Unmatched addresses generally result from either a problem with the address or a problem in the reference data. If a problem is observed with the address, it can be corrected and matched with the correct candidate directly on this screen. Often, however, it is unclear what the problem is with a particular address, and additional research is required to determine where the problem lies before it can be corrected.

3.2 Conflation

Conflation, in the context of GIS, is the process of combining two geospatial datasets so that the resultant dataset is superior to the input datasets. While conflation processes are used throughout GIS, they are of particular importance in GIS-T where roadway datasets of varying spatial quality and attribution are available from many different sources. The act of conflating datasets can often be a complex and time-consuming process. How complex and time-consuming the process is depends on a number of factors including the spatial extent of the datasets, the number of features present and the degree of spatial alignment between corresponding features. In some cases, it may be possible to automate a portion of the process but the success of these types of approaches depends on the quality of the initial datasets and the requirements for the final product.

Reference Dataset

When conflating two datasets, one of the datasets is generally considered to be the reference or target dataset. This is the dataset with the most spatially accurate features. The other dataset is sometimes referred to as the input or source dataset.

Conflation Workflow

While each conflation project can be unique, they all draw from a core set of activities. Some of the more common conflation activities include the following:

- Feature Matching: The objective here is to match corresponding features in the datasets. This process can be based on the spatial alignment of the features and/or certain attributes of the features.

- Feature Alignment: Once features are matched, they can be brought into spatial alignment with each other to establish proper topological relationships.

- Feature Addition: Features in the input dataset which are missing in the reference dataset can be added to the reference dataset.

- Attribute Transfer: Attributes information from the input dataset is added to the reference dataset.

The characteristics of the activities involved in a conflation project are largely dependent on the nature of the input datasets. There are three potentials scenarios:

- Vector - Vector

- Vector - Image/Raster

- Image/Raster - Image/Raster

In GIS-T, we are most commonly engaged in conflating two vector datasets (i.e., roadway data).

Horizontal Conflation vs. Vertical Conflation

Conflation can also be broadly categorized as horizontal conflation or vertical conflation based on the geographic relationship between the datasets. In horizontal conflation, the objective is to join two datasets which are spatially adjacent to each other. For example, perhaps you want to join roadway datasets from two adjacent counties or two adjacent states. In these cases, there is often some feature overlap near the dataset boundaries. In vertical conflation, the datasets being merged span the same geographic region or at least have substantial overlap. The objective is often to transfer a robust set of attribute data from one dataset, which may be of poor spatial accuracy, to a dataset which is poor in attribution but spatially accurate. Of course, in the real world, you may run across situations where the datasets partially overlap.

Conflation Tools

GIS software often has some built-in tools to at least assist with conflation needs. For example, in ArcMap 10.2.1, ESRI introduced a set of tools to help with conflation. The conflation toolset is found in the Editing Toolbox. ESRI also added a tool called Detect Feature Changes to the Data Comparison toolset in the Data Management Toolbox. Spend some time reviewing the help documentation for these tools.

3.3 Getting to Know a Transportation Organization

This week, we’ll take some time to explore Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs) and Rural Planning Organizations (RPOs). MPOs were formed as part of 1962 Federal-Aid Highway Act and are required for any urbanized area with a population of more than 50,000. Congress recognized transportation planning is best done at a regional level since the nature of transportation systems and services often transcends an individual municipality, city, or county.

Watch the short video (11 minutes) below which discusses the purpose and structure of MPOs. There are more than 300 MPOs across the U.S., a listing of which is provided here [43].

Video: MPO Planning Process (11:27)

NARRATOR: Transportation is the backbone of our communities. We rely on it every day to get us to work, to get us to shopping and recreation, and to bring us goods and services. But who makes the decisions about our transportation system, and how are those decisions made? This video is an introduction to Metropolitan Transportation Planning and the role of metropolitan planning organizations.

Over the last 100 years or more, America's population and lines of commerce have expanded well beyond the boundaries of individual cities and towns. Today, networks of highways, transit services, freight carriers, and airports serve metropolitan areas that may include many cities, suburbs, towns, and counties. In today's urban areas, many transportation decisions are best handled at the regional level. A regional approach gives decision-makers a comprehensive understanding of transportation problems and the ability to develop comprehensive solutions.

Over the years, Congress has promoted a regional approach to urban transportation planning and decision-making. One of the most important advances came in the 1970s with legislation that required the creation of metropolitan planning organizations or MPOs in areas with a population of 50,000 or more. Now, there are over 300 MPOs across the country. An MPO may be a free-standing planning organization or an association of local governments, but every MPO is governed by a policy board of local elected officials. The Board may also include representatives from state transportation departments, mass transit operators, and others. The MPO is not alone in the decision-making process, but it's the engine that drives collaboration and cooperation among many participants. Local elected officials bring a unique perspective to the planning and decision-making process. They often face a challenging balancing act, making decisions that have the greatest regional benefit, while at the same time reflecting the concerns of the communities they represent.

MPOs and their partners produce three key documents: the Unified Planning Work Program, the Transportation Plan, and the Transportation Improvement Program. The Unified Planning Work Program (or UPWP) describes the planning studies that are being performed for the metropolitan area. The Transportation Plan identifies the region's transportation policies, strategies, and projects for the next twenty years or more. The Transportation Improvement Program (or TIP) is a short-range program of projects covering at least three years that directs available funds to those improvements that are the highest priority. The MPO Policy Board and its partners direct the development and content of the Plan, the TIP, and the UPWP. Both the Plan and the TIP must be fiscally constrained, in other words, consistent with available and expected funds. In areas with air quality problems, the Plan and the TIP must also help the region meet federal standards.

Let's now look at how the Plan and the TIP are prepared. Often the local planning participants start with a regional vision or a set of goals. This vision expresses what the region would like to become perhaps forty or fifty years in the future.

LES STERMAN: Well, important elements of a long-range plan are obviously a strong statement of goals and values, what is it that we're after, and transportation systems in the future.

NARRATOR: In developing a vision or goals, the MPO may consider many questions: What are the trends in regional growth, and are they desirable? How well is the transportation system performing? Do existing plans deal with current and expected problems? Can the transportation system support the kinds of future development that the region desires? When the vision and goals are in place, the MPO and its partners are better able to identify transportation problems and needs. These can include declining mobility, increasing congestion, poor access to jobs in neighborhoods, unhealthy air, or inconsistency with proposed economic development. An understanding of these problems allows the MPO and its partners to identify alternatives to improve transportation. Alternatives may include new policies, operational strategies, or capital projects. Some may help the existing system work better. Others may expand or build new transit lines, highways, and other facilities. Another round of questions is asked in assessing the impact of alternatives. How well does each alternative address the region's transportation problems? What are the likely impacts on neighborhoods and the environment? How much do the alternatives cost? Are the funds there, and is this the best use of available resources? The answers to these questions help the board choose the best alternatives. By adopting the Transportation Plan, the board establishes the policies, strategies, and projects that the region will pursue.

To develop the TIP, priority projects are drawn from the adopted Transportation Plan and matched with available funding. Once adopted by the MPO, the TIP is submitted to the state and becomes part of the statewide transportation improvement program, but the process doesn't end here. Projects and strategies in the plan and TIP undergo further development, often including engineering and environmental studies. Also, many MPOs monitor the implementation of the plan and TIP, study how well the plan is working, and make periodic adjustments. Federal rules require that the plan be updated and readopted every three to five years, and the TIP every two years.

RAE RUPP SRCH: Long-range planning, it is an ongoing process. It's not etched in stone, and many people don't realize that. New board members don't realize that either, that it's not a plan etched in stone. That, you know, it's constantly in an updating process.

NARRATOR: Agency and public involvement is a key activity in every step of the planning process. The public refers to a variety of individuals, agencies, and organizations each with different interests and levels of involvement. Many different approaches are used to inform and engage other agencies and the public.

CHARLES UKEGBU: Our public participation is not just at the MPO level, and that's one of the things we try to emphasize at the municipal level. It is not just the MPO calling a meeting, no, it is the MPO participating in other meetings and forums that may have been called by other, whether city or state agencies.