Deep Time: Stratigraphy and the Sedimentary Record

(With apologies to the great detective.) "Holmes, did you realize that this chess board is exactly 12 inches long?" I asked, as we sat across the table in our Baker Street lodgings.

"Come, Watson. The game is a foot," he replied. "We must explain the Giant Splat of Sue Matra's birthday."

"The Giant Splat? Holmes, I know that Sue Matra is a friend of your brother Mycroft, but how came she to have a giant splat on her birthday?"

"Sue returned home from her job as a scientist measuring the air speed of swallows carrying coconuts, and discovered a splat on the floor. Here is a brief diagram of the situation."

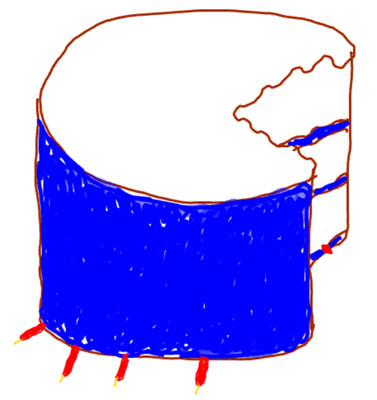

Holmes rapidly sketched the following:

"This takes the cake," I commented sweetly, after looking at the diagram carefully.

"No," he replied, "The cake was left on Sue's study floor."

"Holmes," I said, "You know that my medical training exposed me to the scientific method and that in my military experience I conducted forensic investigations, learning what people died of. I was even exposed to geology and paleontology during my studies at the college. Your science of detection shares much with forensic medicine, and with the fields of geology and paleontology. Something has happened, and you try to determine what."

"Indeed, Watson, I am aware that you are among those few individuals who have been trained to reason from effects to causes, so unusual in a world full of people who reason only from causes to effects."

"But it is more than that, Holmes. When faced with an effect, we quickly try to think of all possible causes that are consistent with the available data and with our other knowledge about the world—call these 'multiple working hypotheses'. Then, we see what each of them predicts that we might discover or measure—each possible hypothesis is a cause, and we reason to its effects, in the same way that other people reason from causes to effects. But we go further, and we make those measurements or observations that will identify the effects of each of our likely causes, using the results to eliminate some of the hypotheses. For example, if we postulate that a horse stomped on the cake to make the giant splat, then we expect the mark of a horseshoe in the cake."

"Even if the horse missed, the shaking of the ground might have caused the cake to fall. Close counts in horseshoes and hand grenades, as you know."

"I ignored his attempted witticism, and said, "Holmes, allow me to send a few telegrams to test some hypotheses, and we will soon have the answers."

An hour later, I was ready to explain the giant splat to Holmes. "Sue Matra is married to a diligent and helpful husband, who is also an amateur cook. He confirms that he was baking a birthday cake for Sue, and made it in three layers, putting down a layer of cake, then icing, cake, icing, cake, icing. Then, he put candles in, and carefully carried the cake across the study toward a table. Unfortunately, the couple owns a large and boisterous retrieving dog, which jumped up and took a large bite out of the cake."

"The curious incident of the dog in the daytime," Holmes muttered.

"Yes," I said, "the dog did much in the daytime. You will notice that your highly accurate sketch shows that the dog's bite has severed the candle, and that the candle was shoved through the icing, so the order of events is clear. The actions of the dog so surprised the husband that he dropped the cake, which was unbalanced by the dog anyway. Given the height from which it dropped, and the rotation imparted by the dog, the cake flipped halfway over and splatted to the floor. The husband, distraught, and worried lest the suddenly sweetened canine should have an accident on the floor, took the beast for a walk, and during this interval, Sue returned home and discovered the splat."

"And how," asked Holmes, "did you determine that the dog bite occurred before the splat."

"If the splat occurred first and the dog then bit the splatted cake, the bite would not run smoothly through the whole thickness of cake, or else the dog's teeth would have scarred the floor or become stuck in the wood, yet the bite through the cake runs smoothly the whole way."

"Well," said Holmes, "I hope they have some good old H2O to clean up the mess."

"Elementary, Holmes," I replied, "elementary."

Could you have explained Sue's splat? If so, you understand some of the secrets of being a geologist. If not, then stick with us, and you should have it figured out by the end of the unit.

What to do for Unit 9?

You will have one week to complete Unit 9. See the course calendar for specific due dates.

As you work your way through the online materials for Unit 9, you will encounter a video lecture, several vTrips, some animated diagrams (called GeoMations and GeoClips), additional reading assignments, a practice quiz, a "RockOn" quiz, and a "StudentsSpeak" Survey. The chart below provides an overview of the requirements for this unit.

| REQUIREMENTS | SUBMITTED FOR GRADING? |

|---|---|

| Read/view all of the Instructional Materials | No, but you will be tested on all of the material found in the Unit 9 Instructional Materials. |

| Continue working on Exercise #5: Puzzling Out Relative Time | Yes, this is the fifth of 6 Exercises and is worth 5% of your total grade. |

| Take the Unit 9 "RockOn" quiz | Yes, this is the ninth of 12 end-of-unit RockOn quizzes and is worth 4.5% of your total grade. |

| Complete the "StudentsSpeak #10" survey | Yes, this is the tenth of 12 weekly surveys and is worth 1% of your total grade. |

Questions?

Please feel free to email "All Teachers" and "All Teaching Assistants" through Canvas conversations with any questions.

Keep Reading!

On the following pages, you will find all of the information you need to successfully complete Unit 9, including the online textbook, a video lecture, several vTrips and animations, and an overview presentation.

Students who register for this Penn State course gain access to assignment and instructor feedback, and earn academic credit. Information about registering for this course is available from the Office of the University Registrar.