17. Satellite Ranging

GPS receivers calculate distances to satellites as a function of the amount of time it takes for satellites' signals to reach the ground. To make such a calculation, the receiver must be able to tell precisely when the signal was transmitted and when it was received. The satellites are equipped with extremely accurate atomic clocks, so the timing of transmissions is always known. Receivers contain cheaper clocks, which tend to be sources of measurement error. The signals broadcast by satellites, called "pseudo-random codes," are accompanied by the broadcast ephemeris data that describes the shapes of satellite orbits.

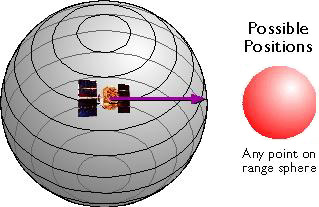

The GPS constellation is configured so that a minimum of four satellites is always "in view" everywhere on Earth. If only one satellite signal was available to a receiver, the set of possible positions would include the entire range sphere surrounding the satellite.

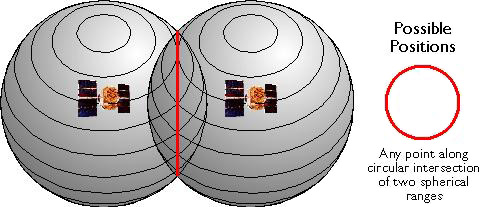

If two satellites are available, a receiver can tell that its position is somewhere along a circle formed by the intersection of two spherical ranges.

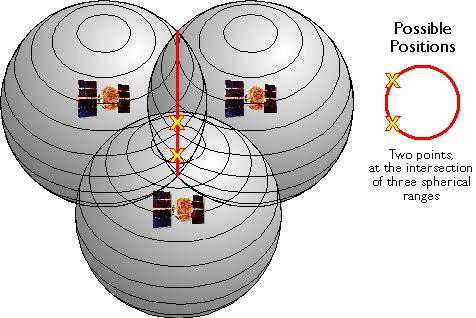

If distances from three satellites are known, the receiver's position must be one of two points at the intersection of three spherical ranges. GPS receivers are usually smart enough to choose the location nearest to the Earth's surface. At a minimum, three satellites are required for a two-dimensional (horizontal) fix. Four ranges are needed for a three-dimensional fix (horizontal and vertical).

Satellite ranging is similar in concept to the plane surveying method trilateration, by which horizontal positions are calculated as a function of distances from known locations. The GPS satellite constellation is in effect an orbiting control network.

Try This!

Trimble has a tutorial "designed to give you a good basic understanding of the principles behind GPS without loading you down with too much technical detail". Check it out at Trimble. Click "Why GPS?" to get started.