Chapter 3 - Structured Analytic Techniques

Chapter 3 Overview

Geospatial analysis can be very difficult to do well. Much of the difficulty is cognitive and not related to an individual's ability to use the technical tools, i.e., GIS. It takes far greater mental agility than gathering evidence supporting a single hypothesis that was pre-judged as the most likely answer. To develop and retain multiple spatial schemes in working memory and note how each item of information fits into each hypothesis is beyond the mental capabilities of most analysts. (Note: Working memory tasks include the active monitoring or manipulation of information or behaviors.)

Moreover, truly good geospatial analysis requires monitoring your progress, making changes and adapting the ways you are thinking. It is about self-reflection, self-responsibility, and initiative to achieve the analytic results within the time allotted. This mental agility can be accomplished with the help of a few simple thinking tools discussed here.

Challenging Mindsets

Heuer makes three important points relative to intelligence in his work, the Psychology of Intelligence Analysis [1].

- Human minds are ill equipped ("poorly wired") to cope effectively with both inherent and induced uncertainty.

- Increased knowledge of one's own inherent biases tends to be of little assistance to the analyst.

- Tools and techniques that apply higher levels of critical thinking can substantially improve analysis of complex problems.

He provides the following series of images to illustrate how poorly we are cognitively equipped to accurate interpret the world.

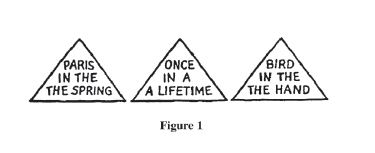

Question #1: What did you see in the figure? The answer is at the bottom of this page.

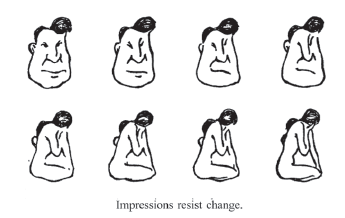

Question #2: Look at the drawing of the man in the upper right. Are the drawings all of men? The answer is at the bottom of this page.

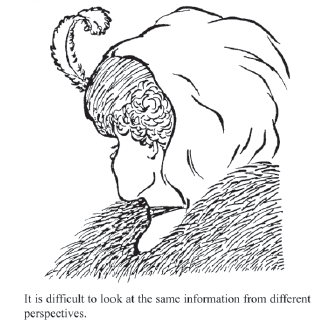

Question #3: What do you see—an old woman or a young woman? The answer is at the bottom of this page.

Now look to see if you can reorganize the drawing to form a different image of a young woman, if your original perception was of an old woman, or of the old woman if you first perceived the young one.

According to Heuer, and as the above figures illustrate, mental models, or mindsets, or cognitive patterns are essentially the analogous image by which people perceive information. Even though every analyst sees the same piece of information, it is interpreted differently due to a variety of factors. In essence, one's perceptions are morphed by a variety of factors that are completely out of the control of the analyst. Heuer sees these cognitive patterns ;as potentially good and bad for the analyst. On the positive side, they tend to simplify information for the sake of comprehension but they also bias interpretation. The key risks of mindsets are that:

- analysts perceive what they expect to perceive;

- once formed, they are resistant to change;

- new information is assimilated, sometimes erroneously, into existing mental models; and

- conflicting information is often dismissed or ignored.

Therefore, since all people observe the same information with inherent and different biases, Heuer believes an effective analysis method needs a few safeguards. The analysis method should:

- encourage products that clearly show their assumptions and chains of inferences; and

- emphasize procedures that expose alternative points of view.

What is required of analysts is a process for challenging, refining, and challenging their own working mental models. This is a key component of his Structured Analytic Techniques (SATs), which include Analysis of Competing Hypotheses.

These problems notwithstanding, cognitive patterns are critical to allowing individuals to process what otherwise would be an incomprehensible volume of information. Yet, they can cause analysts to overlook, reject, or forget important incoming or missing information that is not in accord with their assumptions and expectations. Seasoned analysts may be more susceptible to these mindset problems as a result of their expertise and past success in using time-tested mental models.

Answers

Answer #1: The article is written twice in each of the three phrases. This is commonly overlooked because perception is influenced by our expectations about how these familiar phrases are normally written.

Answer #2: The above figure illustrates that mind-sets tend to be quick to form but resistant to change by showing part of a longer series of progressively modified drawings that change almost imperceptibly from a man into a woman. The right-hand drawing in the top row, when viewed alone, has equal chances of being perceived as a man or a woman.

Answer #3: The old woman’s nose, mouth, and eye are, respectively, the young woman’s chin, necklace, and ear. The old woman is seen in profile looking left. The young woman is also looking left, but we see her mainly from behind so most facial features are not visible. Her eyelash, nose, and the curve of her cheek may be seen just above the old woman’s nose.

The Structured Analytic Techniques "Toolbox"

Structured analytic techniques are simply a "box of tools" to help the analyst mitigate the adverse impact on analysis of one's cognitive limitations and pitfalls. Taken alone, they do not constitute an analytic method for solving geospatial analytic problems. The most distinctive characteristic is that structured techniques help to decompose one's geospatial thinking in a manner that enables it to be reviewed, documented, and critiqued. "A Tradecraft Primer: Structured Analytic Techniques for Improving Intelligence Analysis [2]" (CIA, 2009) highlights a few structured analytic techniques used in the private sector, academia, and the intelligence profession.

Structured thinking in general and structured geospatial thinking specifically is at variance with the way in which the human mind is in the habit of working. Most people solve geospatial problems intuitively by trial and error. Structured analysis is a relatively new approach to intelligence analysis with the driving forces behind the use of these techniques being:

- an increased understanding of cognitive limitations and pitfalls that make intelligence analysis difficult;

- prominent intelligence failures that have prompted reexamination of how intelligence analysis is generated;

- DNI policy support and technical support for interagency collaboration; and

- a desire by policy makers who receive analysis that it be more transparent as to how conclusions were reached.

In general, the Intelligence Community began focusing on structured techniques because analytic failures led to the recognition that it had to do a better job overcoming cognitive limitations, analytic pitfalls, and addressing the problems associated with mindsets. Structured analytic techniques help the mind think more rigorously about an analytic problem. In the geospatial realm, they ensure that our key geospatial assumptions, biases, and cognitive patterns are not just assumed correct but are well considered. The use of these techniques later helps to review the geospatial analysis and identify the cause of any error.

Moreover, structured techniques provide a variety of tools to help reach a conclusion. Even if both intuitive and scientific approaches provide the same degree of accuracy, structured techniques have value in that they can be easily used to balance the art and science of their analysis. It is clear is that structured methodologies are severely neglected by the geospatial community. Even in the rare cases where a specific technique is used, no one technique is appropriate to every step of the problem solving process.

There are two ways to view the nature of these techniques. Heuer categorized structured techniques by how they help analysts overcome human cognitive limitations or pitfalls to analysis. Heuer's grouping is as follows:

- Decomposition and Visualization: The number of things most people can keep in working memory at one time is seven, plus or minus two. Complexity increases geometrically as the number of variables increases. In other words, it is very difficult to do error-free analysis only in our heads. The two basic tools for coping with complexity in the analysis are to: (1) break things down into their component parts, so that we can deal with each part separately, and (2) put all the parts down on paper or a computer screen in some organized manner such as a list, matrix, map, or tree so that we and others can see how they interrelate as we work with them. Many common techniques serve this purpose.

- Indicators, Signposts, Scenarios: The human mind tends to see what it expects to see and to overlook the unexpected. Change often happens so gradually that we do not see it, or we rationalize it as not being of fundamental importance until it is too obvious to ignore. Identification of indicators, signposts, and scenarios create an awareness that prepares the mind to recognize change.

- Challenging Mindsets: A simple definition of a mindset is “a set of expectations through which a human being sees the world.” Our mindset, or mental model of how things normally work in another country, enables us to make assumptions that fill in the gaps when needed evidence is missing or ambiguous. When this set of expectations turns out to be wrong, it often leads to intelligence failure. Techniques for challenging mindsets include reframing the question in a way that helps break mental blocks, structured confrontation such as devil’s advocacy or red teaming, and structured self-critique such as what we call a key assumption check. In one sense, all structured techniques that are implemented in a small team or group process also serve to question your mindset. Team discussions help us identify and evaluate new evidence or arguments and expose us to diverse perspectives on the existing evidence or arguments.

- Hypothesis Generation and Testing: “Satisficing” is the tendency to accept the first answer that comes to mind that is “good enough.” This is commonly followed by confirmation bias, which refers to looking at the evidence only from the perspective of whether or not it supports a preconceived answer. These are among the most common causes of intelligence failure. Good analysis requires identifying, considering, and weighing the evidence both for and against all the reasonably possible hypotheses, explanations, or outcomes. Analysis of Competing Hypotheses is one technique for doing this.

- Group Process Techniques: Just as analytic techniques provide structure to our individual thought processes, they also provide structure to the interaction of analysts within a team or group. Most structured techniques are best used as a collaborative group process, because a group is more effective than an individual in generating new ideas and at least as effective in synthesizing

divergent ideas. The structured process helps identify differences in perspective between team or group members, and this is good. The more divergent views are available, the stronger the eventual synthesis of these views. The specific techniques listed under this category, such as brainstorming and Delphi, are designed as group processes and can only be implemented in a group.

Others have grouped techniques by their purpose:

- Diagnostic techniques are primarily aimed at making analytic arguments, assumptions, or intelligence gaps more transparent;

- Contrarian techniques explicitly challenge current thinking; and

- Imaginative thinking techniques aim at developing new insights, different perspectives and/or develop alternative outcomes. In fact, many of the techniques will do some combination of these functions.

These different groupings of the techniques notwithstanding, the analysts should select the technique that best accomplishes the specific task they set out for themselves. The techniques are not a guarantee of analytic precision or accuracy of judgments; they do improve the usefulness, sophistication, and credibility of intelligence assessments.

SATs and Geospatial Operations

It is often difficult for an analyst to determine the next step in an analytic process or to visualize how various techniques and tools fit together. Using the below as a list of the common GIS operations, the analyst might use:

- data entry;

- data conversion;

- data validation;

- spatial data management;

- attribute data management;

- data visualization;

- data processing/analysis and

- output of maps and reports.

The Structured Geospatial Analytic Method (SGAM) provides the means to relate the analytical step to the Structured Analytic Technique (SAT) and then to the appropriate geospatial operation. The following table summarizes this mapping:

|

Structured Geospatial Analytic Method Step |

Structured Analytic Technique | GIS Operation |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Question |

|

|

|

Step 2: Grounding

|

|

|

| Step 3: Hypothesis Development |

|

|

| Step 4: Evidence Development |

|

|

| Step 5: Fusion |

|

|

| Step 6: Conclusions |

|

|

The Intelligence Community began to use structured techniques because of analytic failures related to cognitive limitations and pitfalls or biases. The use of SATs does not guarantee getting intelligence analysis right, because there are so many uncertainties. SATs help to reduce the frequency and severity of error. These include SATs that partially overcome cognitive limitations, address analytic pitfalls, and confront the problems associated with mindsets. SATs help the mind think more rigorously about an analytic problem. Specifically, they ensure that assumptions, preconceptions, and mindsets are not taken for granted but are explicitly examined and tested. The use of SATs also helps to review the analysis and identify the cause of any error.