Key Definitions and Concepts

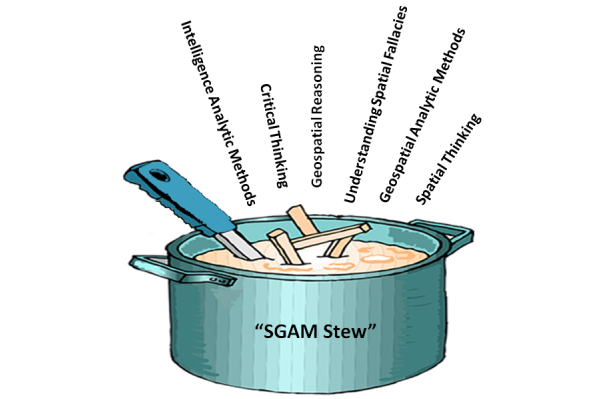

A number of "ingredients" (concepts) have been used in the development of the Structured Geospatial Analysis Method "stew." It is difficult to understand how to apply the method without understanding the ingredients and their associated qualities. The following is a brief discussion of each ingredient for your general reference:

- critical thinking

- spatial thinking

- understanding spatial fallacies

- geospatial reasoning

- analytic methods

- geospatial analytic methods

Recipe for SGAM Stew

Ingredients

- 1 tablespoon of critical thinking

- 1 1/2 pounds intelligence analytic methods

- 1/2 cup geospatial analytic methods

- 1/2 cup sliced understanding spatial fallacies

- 3 cups spatial thinking

- 1 cup geospatial reasoning

- salt and pepper, to taste

Preparation:

In a large saucepan brown the intelligence analytic method; add the geospatial analytic method and sauté for 3 to 5 minutes longer. Add reasoning and spatial thinking; bring to a boil. Reduce heat to low, cover, and simmer for 1 to 1 1/2 hours. Add geospatial reasoning; simmer for about 30 to 40 minutes longer, or until tender. Add drained critical thinking; continue cooking for 5 to 10 minutes.

In a small bowl or cup, combine additional spatial thinking and geospatial reasoning with cold water until smooth. Add the mixture to the simmering broth, a little at a time, until stew is thickened. Taste and add salt and pepper. Serve with hot buttered presentations.

Critical Thinking

There is a great deal of confusion about what critical thinking is and its relationship to an analytical method. Much of the confusion is because there are many definitions of critical thinking. According to Cohen and Salas (Marvin S. Cohen and Eduardo Salas, Critical Thinking: Challenges, Possibilities, and Purpose, March 2002), definitions in the literature suggest that a common core meaning exists, and one might define critical thinking as:

The deliberate evaluation of intellectual products in terms of an appropriate standard of adequacy.

Related to this definition is a theme of early philosophers, such as Descartes, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume, of the importance of challenging inherited and customary beliefs. In other words, to adopt not only a first-person, but also a second-person critical point of view. This imperative of doubting one’s own accepted beliefs is critical thinking. The early philosophers agreed on two things about critical thinking:

- Its purpose is to fulfill an ethical duty to think properly about whether to accept or reject each of our beliefs.

- A constraint on proper thinking about belief acceptance is that it must be based upon good evidence.

Initially evidence was regarded as sufficient only if it guaranteed the truth of a conclusion. Today, theorists acknowledge uncertainty about matters of fact and even about logic. The purpose of critical thinking is, therefore, now seen as to ensure a high probability of truth.

More recently, in 2002, Robert H. Ennis, Retired Director, Illinois Critical Thinking Project, wrote that, "Critical thinking is here assumed to be reasonable reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do. This rough overall definition is, we believe, in accord with the way the term is generally used these days. Under this interpretation, critical thinking is relevant not only to the formation and checking of beliefs, but also to deciding upon and evaluating actions. It involves creative activities such as formulating hypotheses, plans, and counterexamples; planning experiments; and seeing alternatives. Furthermore, critical thinking is reflective -- and reasonable. The negative, harping, complaining characteristic that is sometimes labeled by the word 'critical' is not involved."

In his piece, Super-Streamlined Conception of Critical Thinking, Robert H. Ennis, points out that a critical thinker:

- is open-minded and mindful of alternatives;

- tries to be well-informed;

- judges well the credibility of sources;

- identifies conclusions, reasons, and assumptions;

- judges well the quality of an argument, including the acceptability of its reasons, assumptions, and evidence;

- can well develop and defend a reasonable position;

- asks appropriate clarifying questions;

- formulates plausible hypotheses; plans experiments well;

- defines terms in a way appropriate for the context;

- draws conclusions when warranted, but with caution; and

- integrates all items in this list when deciding what to believe or do.

Richard Paul has further defined it as:

Critical thinking is that mode of thinking – about any subject, content or problem – in which the thinker improves the quality of his or her thinking by skillfully taking charge of the structures inherent in thinking and imposing intellectual standards upon them. (Paul, Fisher and Nosich, 1993, p.4)

Alec Fisher, Critical Thinking: An Introduction, Cambridge University Press, points out that, "This definition draws attention to a feature of critical thinking on which teachers and researchers in the field seem to be largely agreed, that the only way to develop one's critical thinking ability is through 'thinking about one's thinking' (often called 'metacognition'), and consciously aiming to improve it by reference to some model of good thinking in that domain."

The essence is that critical thinking in geospatial intelligence is exemplified by asking questions about alternative possibilities in order to achieve some objective analysis rendering a high probability of the selected alternative being true.

Spatial Thinking

To paraphrase William Millwood, creating geospatial analysis requires transformations resulting from an intellectual endeavor that sorts the significant from the insignificant, assessing them severally and jointly, and arriving at a conclusion by the exercise of reasoned judgment. This endeavor when dealing with geospatial problems is geospatial reasoning, or an operation in which present facts suggest other facts. Geospatial reasoning creates an objective connection between our present geospatial beliefs and the evidence for believing something else.

Spatial thinking includes processes that support exploration and understanding. An expert spatial thinker visualizes relations, imagines transformations from one scale to another, mentally rotates an object to look at its other sides, creates a new viewing angle or perspective, and remembers images in places and spaces. Spatial thinking also allows us to externalize these operations by creating representations such as a map.

Spatial thinking begins with the ability to use space as a framework. An object can be specified relative to the observer, to the environment, to its own intrinsic structure, or to other objects in the environment. Each instance requires the adoption of specific spatial frames of reference or context. The process of interpretation begins with data which is generally context-free numbers, text, or symbols. Information is derived from data by implying some degree of selection, organization, and preparation for a purpose — in other words, the data is placed into a spatial context. For example, the elevation at a specific location is an example of data; however, the elevation only has meaning when placed in context of sea level. The spatial context is critical because it is the space the data is in that ultimately determines its interpretation. There are three spatial contexts within which we can make the data-to-information transition; these include life spaces, physical spaces, and intellectual spaces. In all cases, space provides an interpretive context that gives meaning to the data.

- Life space is the four-dimensional space-time where spatial thinking is a means of coming to grips with the spatial relations between self and objects in the physical environment. This is cognition in space and involves thinking about the world in which we live. It is exemplified by navigation and the actions that we perform in space.

- Physical space is also built on the four-dimensional world of space-time, but focuses on a scientific understanding of the nature, structure and function of phenomena. This is cognition about space and involves thinking about the ways in which the "world" works. An example might be how an earthquake creates a tsunami.

- Intellectual space is in relationship to concepts and objects that are not in and of themselves necessarily spatial, but the nature of the space is defined by the particular problem. This is cognition with space and involves thinking with or through the medium of space in the abstract. An example might be the territorial dispute between two ethnic groups.

Learning to think spatially is to consider objects in terms of their context. This is to say, the object's location in life space, physical space, or intellectual space, to question why objects are located where they are, and to visualize relationships between and among these objects. The key skills of spatial thinking include the ability to:

- Understand the context. The significance of context was discussed above, but it is important to say that if the data upon which the decision is based are placed into the wrong spatial context, for example, life space rather than intellectual space, it is likely the analysis will be flawed.

- Recognize spatial schemes (patterns and shapes). The successful spatial thinker needs to retain an image of the simple figure in mind, and look for it by suppressing objects irrelevant to a task at hand. This ability allows a geospatial analyst to identify patterns of significance in a map, such as an airfield.

- Recall previously observed objects. The ability to recall an array of objects that was previously seen is called object location memory.

- Integrate observation-based learning. Synthesizing separately made observations into an integrated whole. The expert analyst moves through the data, gathering information from separately observed objects and views, and integrates this information into a coherent mental image of the area.

- Mental rotating an object and envisioning scenes from different viewpoints. The ability to imagine and coordinate views from different perspectives has been identified by Piaget and Inhelder (1967) as one of the major instances of projective spatial concepts. Mental-rotation ability or perspective-taking ability could be relevant to those analysis tasks that involve envisioning what an object, such as a building, would look like if seen from another position.

Golledge’s First-Order Primitives constitute a broad list of cognitive schemes for geospatial analysis (R. G. Golledge "Do People Understand Spatial Concepts: The case of First-Order Primitives", Theories and Models of Spatio-Temporal Reasoning in Geographic Space. Pisa: Springer-Verlag, 1992). The schemas are:

- Location. This includes a descriptor with identity, magnitude, location and time. An additional cognitive component might be familiarity. Occurrences are often called environmental cues, nodes, landmarks, or reference points.

- Spatial distributions. Distributions have a pattern, a density, and an internal measure of spatial variance, heterogeneity or dispersion; occurrences in distributions also have characteristics such as proximity, similarity, order, and dominance.

- Regions. Areas of space in which either single or multiple features occur with specified frequency (uniform regions) or over which a single feature dominates.

- Hierarchies. Multiple levels or nested levels of phenomena including features.

- Networks. Linked features having characteristics, connectivity, centrality, diameter, and density. Networks may also include physical links such as transportation systems, or non-visual systems.

- Spatial associations. Associations include spatial autocorrelation, distance decay, and contiguities. Examples of these associations include interaction frequencies or geographic and areal associations. For example, the coincidence of features within specific areas (i.e., squirrels are normally near trees) is a spatial association.

- Surfaces. There are generalizations of discrete phenomena, including densities of occurrence, flows over space and through time (as in the spatial diffusion of information or phenomena).

Geospatial Reasoning

Reasoning

The three well known reasoning processes trace the development of analytic beliefs along different paths. Inductive reasoning reveals “that something is probably true," deductive reasoning demonstrates “that something is necessarily true.” It is generally accepted within the intelligence community that both are limited: inductive reasoning leads to multiple, equally likely solutions, and deductive reasoning is subject to deception. Therefore, a third aid to judgment, abductive reasoning, showing “that something is plausibly true,” is used to offset the limitations of the others. While analysts who employ all three guides to sound judgment stand to be the most persuasive, fallacious reasoning or mischaracterization of rules, cases, or results in any of the three can affect reasoning using the others.

- Inductive reasoning, moving from the specific case to the general rule, suggests many possible outcomes, or the range of what might happen in the future. However, inductive reasoning lacks a means to distinguish among outcomes. An analyst has no way of knowing whether a solution is correct.

- Deductive reasoning, on the other hand, moves from the general to the specific. Deductive reasoning becomes essential for predictions. Based on past perceptions, certain facts indicate specific outcomes. If, for example, troops are deployed to the border, communications are increased, and leadership is in defensive bunkers, then war is imminent. However, if leadership remains in the public eye, then these preparations indicate that an exercise is imminent.

- Abductive reasoning reveals plausible outcomes. Abductive reasoning is the process of generating the best explanation for a set of observations. When actions defy accurate interpretation through existing paradigms, abductive reasoning generates novel means of explanation. In the case of predictions, an abductive process presents an “assessment of probabilities.” Although abduction provides no guarantee that the analyst has chosen the correct hypothesis, the probative force of the accompanying argument indicates that the most likely hypothesis is known and that actionable intelligence is being developed.

Geospatial Reasoning

It is not too far of a stretch to say that people who are drawn to the discipline of geospatial intelligence have minds accustomed to assembling information into three-dimensional mental schemas. We construct schemas in our mind, rotate them, and view them from many angles. Furthermore, the experienced geospatial professional imagines spatial schemas influenced in the fourth dimension, time. We mentally replay time series of the schema. So easy is the geospatial professional’s ability to assemble multidimensional models that the expert does it with incomplete data. We mentally fill in gaps, making an intuitive leap toward a working schema with barely enough data to perceive even the most rudimentary spatial patterns. This is a sophisticated form of geospatial reasoning. Expertise increases with experience because as we come across additional schemas, our mind continuously expands to accommodate them. This might be called spatial awareness. Being a visual-spatial learner, instead of feeling daunted by the abundance and complexity of data, we find pleasure in recognizing the patterns. Are we crazy? No, this is what is called a visual-spatial mind. Some also call these people right brain thinkers.

The concept of right brain and left brain thinking developed from the research of psychobiologist Roger W. Sperry. Sperry discovered that the human brain has two different ways of thinking. The right brain is visual and processes information in an intuitive and simultaneous way, looking first at the whole picture then the details. The left brain is verbal and processes information in an analytical and sequential way, looking first at the pieces then putting them together to get the whole. Some individuals are more whole-brained and equally adept at both modes.

The qualities of the Visual-Spatial [1] person are well documented but not well known . Visual-spatial thinkers are individuals who think in pictures rather than in words. They have a different brain organization than sequential thinkers. They are whole-part thinkers who think in terms of the big picture first before they examine the details. They are non-sequential, which means that they do not think and learn in the step-by-step manner. They arrive at correct solutions without taking steps. They may have difficulty with easy tasks, but show a unique ability with difficult, complex tasks. They are systems thinkers who can orchestrate large amounts of information from different domains, but they often miss the details.

Sarah Andrews [2] likens some contrasting thought processes to a cog railway. Data must be in a set sequence in order to process it through a workflow. In order to answer a given question, the thinker needs information fed to him in order. He will apply a standardized method towards arriving at a pragmatic answer, check his results, and move on to the next question. In order to move comfortably through this routine, he requires that a rigid set of rules be in place. This is compared with the geospatial analyst who grabs information in whatever order, and instead of crunching down a straight-line, formulaic route toward an answer, makes an intuitive, mental leap toward the simultaneous perception of a group of possible answers. The answers may overlap, but none are perfect. In response to this ambiguity, the geospatial analyst develops a risk assessment, chooses the best working answer from this group, and proceeds to improve the estimate by gathering further data. Unlike, the engineer, whose formulaic approach requires that the unquestioned authority of the formula exist in order to proceed, the geospatial intelligence professional questions all authority, be it in the form of a human or acquired data.

Analytic Methods in General

It is Sherman Kent, who has been described as the "father of intelligence analysis", that is often acknowledged as first proposing an analytic method specifically for intelligence. [3] The essence of Kent’s method was understanding the problem, data collection, hypotheses generation, data evaluation, more data collection, followed by hypotheses generation (Kent, S. 1949, Strategic intelligence for American world policy, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.).

Richards Heuer subsequently proposed an ordered eight step model of “an ideal” analytic process, emphasizing early deliberate generation of hypotheses prior to information acquisition (Heuer, R. 1981, "Strategies for analytical judgment," Studies in Intelligence, Summer, pp. 65-78.):

- Definition of the analytical problem

- Preliminary hypotheses generation

- Selective data acquisition

- Refinement of the hypotheses and additional data collection

- Data intervention and evaluation

- Hypotheses selection

- Continued monitoring

Heuer’s technique has become known as Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH). The technique entails identifying possible hypotheses by brainstorming, listing evidence for and against each, analyzing the evidence and then refining hypotheses, trying to disprove hypotheses, analyzing the sensitivity of critical evidence, reporting conclusions with the relative likelihood of all hypotheses, and identifying milestones that indicate events are taking an unexpected course. The use of brainstorming is critical since the quality of the hypotheses is dependent on the existing knowledge and experience of the analysts, since hypotheses generation occurs before additional information acquisition augments the existing knowledge of the problem. ACH is widely cited in the intelligence literature as a means for improving analysis. The primary advantage of ACH is a consistent approach for rejection or validation of many potential conclusions (or hypotheses).

Heuer acknowledges how mental models, or mind sets, are essentially the re-representations of how analysts perceive information (Heuer, Richards J. Jr. & Center for the Study of Intelligence 1999, Psychology of intelligence analysis, Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, Washington, DC.). Even though every analyst sees the same piece of information, it is interpreted differently due to a variety of factors (past experience, education, and cultural values to name merely a few). In essence, one's perceptions are morphed by a variety of factors that are completely out of the control of the analyst. Heuer sees mental models as potentially good and bad for the analyst. On the positive side, they tend to simplify information for the sake of comprehension, but they also obscure genuine clarity of interpretation.

ACH has evolved into an eight-step procedure based upon cognitive psychology, decision analysis, and the scientific method. It is believed to be particularly appropriate for establishing an audit trail to show what an analyst considered and how they arrived at their judgment. (Heuer, Richards J. Jr. & Center for the Study of Intelligence 1999, Psychology of intelligence analysis, Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, Washington, DC.).

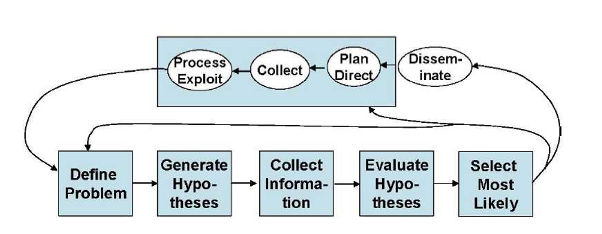

Heuer’s approach is the prevailing view of the analysis process. Figure 1 by the 2002 Joint Military Intelligence College (JMIC) illustrates the integration of the fundamentals of ACH into the intelligence process (Waltz, E. 2003, Toward a MAUI NITE intelligence analytic process model, Veridian Systems, Arlington, VA.).

Figure 1 is particularly significant since it shows the intelligence cycle steps of:

- planning and direction,

- collection,

- processing,

- analysis, and

- dissemination

Which incorporates the following analytic process steps within the analysis steps:

- define the problem,

- develop hypotheses,

- collect information,

- evaluate hypotheses, and

- select the most likely alternative.

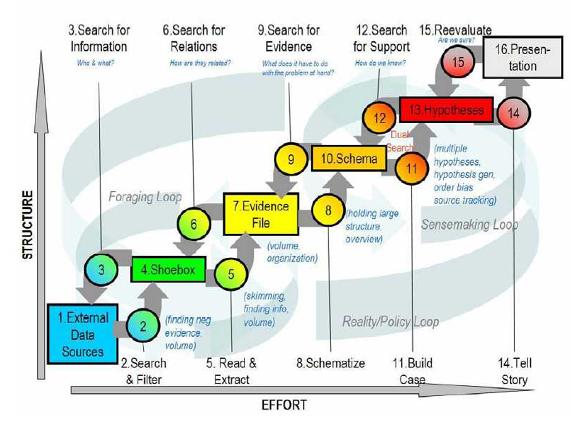

Since Heuer’s development of ACH, another model of the intelligence analysis process is proposed by Pirolli in 2006 which was derived from the results of a cognitive task analysis of intelligence analysts (Pirolli, P.L. 2006, Assisting people to become independent learners in the analysis of intelligence: final technical report, Palo Alto Research Center, Inc., Palo Alto, CA.). The analytic process is described as “A Notional Model of Analyst Sensemaking,” with the cognitive task analysis indicating that the bottom-up and top-down processes shown in each loop are “…invoked in an opportunistic mix.” (Pirolli, P. & Card, S.K. 2006, The sensemaking process and leverage points for analyst technology identified through cognitive task analysis, Palo Alto Research Center, Inc., Palo Alto, CA.). Figure 2 illustrates this process./p>

The term “sensemaking” is used as a term to describe the analysis process.Sensemaking is defined “…as the deliberate effort to understand events,” describing the elements of sensemaking using the terms “data” and “frame.” A frame is “…an explanatory structure that defines entities by describing their relationship to other entities” (Klein, G., Phillips, J.K., Rall, E.L. & Peluso, D.A. 2007, "A data-frame theory of sensemaking" in Expertise out of context, ed. R.R. Hoffman, pp. 113-15). The Klein article further explains that “The data identify the relevant frame, and the frame determines which data are noticed. Neither of these comes first. The data elicit and help to construct the frame; the frame defines, connects and filters the data.”

Pirolli and Card contend that many forms of intelligence analysis are sensemaking tasks. As figure 2 illustrates, such sensemaking tasks consist of information gathering, re-representation of the information in a schema that aids analysis, the development of insight through the manipulation of this representation, and the creation of some knowledge based on the insight. The analyst proceeds through the process of:

They also suggested that the process may be reversed to:

In other words, in terms of Figure 2, the process can be a mix: top-down and/or bottom-up.

Schemas are the re-representation or organized marshaling of the information so that it can be used more easily to draw conclusions. Pirolli and Card note that the re-representation “may be informally in the analyst’s mind or aided by a paper and pencil or computer-based system” (Pirolli, P. & Card, S.K. 2006, The sensemaking process and leverage points for analyst technology identified through cognitive task analysis, Palo Alto Research Center, Inc., Palo Alto, CA.).

Geospatial Analytic Methods

Geospatial Preparation of the Environment (GPE)

- The geospatial intelligence preparation of the environment (GPE) analytic method is based on the intelligence cycle and process. According to the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency(NGA) [4], the steps are:

- 1. Define the Environment: Gather basic facts needed to outline the exact location of the mission or area of interest. Physical, political, and ethnic boundaries must be determined. The data might include grid coordinates, latitude and longitude, vectors, altitudes, natural boundaries (mountain ranges, rivers, shorelines), etc. This data serves as the foundation for the GEOINT product.

- 2. Describe Influences of the Environment: Provide descriptive information about the area defined in Step 1. Identify existing natural conditions, infrastructure, and cultural factors. Consider all details that may affect a potential operation in the area: weather, vegetation, roads, facilities, population, languages, social, ethnic, religious, and political factors. Layer this information onto the foundation developed in Step 1.

- 3. Assess Threats and Hazards: Add intelligence and threat data, drawn from multiple intelligence disciplines, onto the foundation and descriptive information layers (the environment established in the first two steps). This information includes: order-of-battle; size and strength of enemy or threat; enemy doctrine; nature, strength, capabilities and intent of area insurgent groups; effects of possible chemical/biological threats. Step 3 requires collaboration with national security community counterparts.

- 4. Develop Analytic Conclusions: Integrate all information from Steps 1-3 to develop analytic conclusions. The emphasis is on developing predictive analysis. In Step 4, the analyst may create models to examine and assess the likely next actions of the threat, the impact of those actions, and the feasibility and impact of countermeasures to threat actions.

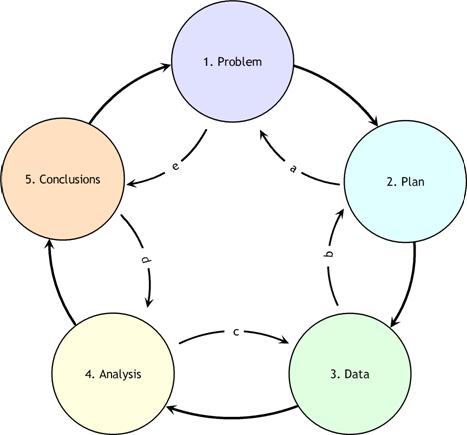

PPDAC: Problem, Plan, Data, Analysis, and Conclusions

De Smith and Goodchild [5] examined geospatial analysis process in the broader context of analytical methodologies. The typical process of geospatial analysis typically follows a number of well-defined and iterative stages:

- problem formulation;

- planning;

- data gathering;

- exploratory analysis;

- hypothesis formulation;

- modeling;

- consultation and review; and

- ultimately, final reporting and/or implementation.

In the whole, geospatial analysis can be seen as part of a decision process and support infrastructure. The process from problem specification to outcome is, in reality, an over-simplification, and the analytical process is more complex and iterative than the steps suggest. GIS and related software tools that perform analytical functions only address data gathering, analysis, and modeling. As de Smith and Goodchild point out, the flow from start to finish is rarely the case. Not only is the process iterative, but at each stage one often looks back to the previous step and re-evaluates the validity of the decisions made. Mackay and Oldford in de Smith and Goodchild [6]described a spatial analysis method in terms of a sequence of steps labeled PPDAC: Problem; Plan; Data; Analysis; and Conclusions. The PPDAC approach is shown in the below figure.

As can be seen from the diagram, although the clockwise sequence (1→5) applies as the principal flow, each stage may, and often will, feed back to the previous stage. In addition, it may well be beneficial to examine the process in the reverse direction, starting with Problem definition and then examining expectations as to the format and structure of the Conclusions. This procedure then continues, step-by-step, in an anti-clockwise manner (e→a) determining the implications of these expectations for each stage of the process.

PPDAC develops evidence. Evidence, in the context of this discussion, refers to the information that is gathered by exploratory analysis of spatial and temporal data. These methods include remote sensing and GIS to develop intermediate products. "Exploratory data analysis (EDA) is about detecting and describing patterns, trends, and relations in data, motivated by certain purposes of investigation. As something relevant is detected in data, new questions arise, causing specific parts to be viewed in more detail. So EDA has a significant appeal: it involves hypothesis generation rather than mere hypothesis testing" (Exploratory Analysis of Spatial and Temporal Data, Springer, 2006). Ultimately, what is evidence is defined by the intelligence producer. Ideally, "evidence" in the context of the framework of the problem should include: the context and the scientific and intuitive evidence.

Understanding Spatial Fallacies

Complex issues in spatial analysis lead to bias, distortion and errors. These issues are often interlinked but various attempts have been made to separate out particular issues from each other. Here is a brief list:

Known Length - Lengths in earth measurement depend directly on the scale at which they are measured and experienced. So while we measure the length of a river, streetet cetera, this length only has meaning in the context of the relevance of the measuring technique to the question under study.

Locational Fallacy - The locational fallacy refers to error due to the particular spatial characterization chosen for the elements of study, in particular choice of placement for the spatial presence of the element. Spatial characterizations may be simplistic or even wrong. Studies of humans often reduce the spatial existence of humans to a single point, for instance their home address. This can easily lead to poor analysis, for example, when considering disease transmission which can happen at work or at school and therefore far from the home. The spatial characterization may implicitly limit the subject of study. For example, the spatial analysis of crime data has recently become popular but these studies can only describe the particular kinds of crime which can be described spatially. This leads to many maps of assault but not to any maps of embezzlement with political consequences in the conceptualization of crime and the design of policies to address the issue.

Atomic Fallacy - This describes errors due to treating elements as separate 'atoms' outside of their spatial context.

Ecological Fallacy - The ecological fallacy describes errors due to performing analyses on aggregate data when trying to reach conclusions on the individual units. It is closely related to the modifiable areal unit problem.

Modifiable areal unit problem - The modifiable areal unit problem (MAUP) is an issue in the analysis of spatial data arranged in zones, where the conclusion depends on the particular shape or size of the zones used in the analysis. Spatial analysis and modeling often involves aggregate spatial units such as census tracts or traffic analysis zones. These units may reflect data collection and/or modeling convenience rather than homogeneous, cohesive regions in the real world. The spatial units are therefore arbitrary or modifiable and contain artifacts related to the degree of spatial aggregation or the placement of boundaries. The problem arises because it is known that results derived from an analysis of these zones depends directly on the zones being studied. It has been shown that the aggregation of point data into zones of different shapes and sizes can lead to opposite conclusions. More detail is available at the modifiable areal unit problem topic entry.