Course Outline

Introduction to Data Management Plans

What is a Data Management Plan (DMP)?

A data management plan is a document that tells how a researcher will collect, document, describe, share, and preserve the data that will be generated as part of a project.

Dr. Andrew Stephenson is Distinguished Professor of Biology and Associate Dean for Research and Graduate Education in the Eberly College of Science at Penn State. As an active researcher, he has generated and collected data for many years and served on many a panel reviewing grant proposals. From his perspective, data management plans make good sense. In the following video, he describes the elements of a DMP and why they are important.

Many funding agencies are now requiring that grant applicants provide information about their data management plan (DMP) as part of their grant proposal. Since 2011 the National Science Foundation (NSF) has required researchers to include DMPs with their grant proposal applications.

DMPs are typically supplemental to a grant application. The NSF specifies that a plan should not exceed two pages. Other funding agencies may have different requirements for length; check with the guidelines of the grant program you are applying for. The NSF also understands that DMPs are not relevant for some projects. In such cases, the agency recommends that the researcher provides a statement explaining why a DMP is not being submitted.

NOTE: There are several directorates in the NSF that have more specific guidance than what follows in this tutorial. It is recommended that you refer to such guidelines (see the list in the Related Resources [3] tab above) if your directorate is included, in addition to taking this tutorial.

Why Do You Need a Data Management Plan?

Obviously, the foremost reason for needing a plan is that agencies such as the NSF, the National Institute of Health (NIH), and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) are requiring DMPs. Hear what Dr. Stephenson has to say about the impact of DMPs on choosing which grants to fund.

There are other reasons, however, why formulating a plan for managing research data is important.

Reason One:

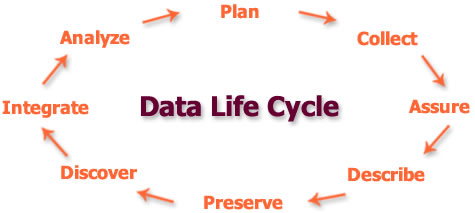

First, a DMP helps you plan and organize your data collection by having you think through the questions that will arise as you gather data. A DMP essentially documents key activities in the research data lifecycle, such as the collection, description, preservation, and access or discovery of data. Such documentation is crucial to reproducibility of research results which is a fundamental precept of scientific investigations.

By laying out the blueprint for lifecycle management of data, a DMP provides valuable details, such as how the data will be preserved for the long term, how and where the researcher will make the data available for sharing, and whether reuse of the data, including derivatives, will be allowed.

Reason Two:

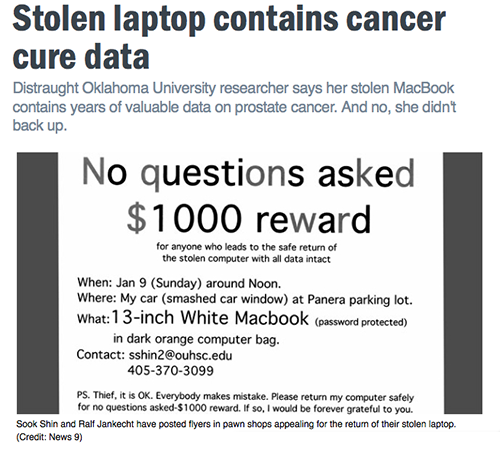

Second, related to reproducibility, a DMP can help prevent or reduce the likelihood of mishaps such as data loss, data errors, and unethical uses of data. In effect, a DMP fosters improved communication and accountability for data.

Reason Three:

Third, data that has been generated by a federally funded project is publicly funded data - that is, data that has been made possible by taxpayer dollars. As such, unless there are restrictions or sensitivities about the data, these are data that should be made available to the public for broad sharing and accessibility.

Finally, having a DMP reflects an understanding that the collected data have intrinsic value, as illustrated in the video below. It can be another source of attribution and further investigations. Indeed, as described by Dr. Alfred Traverse, Curator of the Penn State Herbarium, in the following video, sometimes the collected data is all that remains for further investigations.

Components of a Typical Plan

A DMP basically consists of five parts, in which the following aspects of data are addressed:

Part 1: The types of data to be collected or produced during the project, and the processes or methodology for doing so:

- Types of data that will be generated by your research (e.g., human subjects related surveys, field data, samples, model output data)

- Data format(s) and file types (e.g., .txt, .pdf, .xls, .csv, .jpeg, etc.)

- How the data will be collected or accessed (if using existing data)

Part 2: The formats for the data and the standards that will be followed for documenting and describing the data:

- Information about your data you will need to save (i.e., experimental design, environmental conditions, global positioning information, etc.)

- What metadata standard you will use to document your data (i.e., some research domains have widely accepted formats, others may not and you may target how that decision may be made in the project)

- How you plan to record your metadata

Part 3: The availability of the data, including information about ways in which the data will be accessed, and whether there are any issues related to privacy and/or intellectual property:

- Expected availability of the data during the project period

- List/Explain any ethical or privacy issues incurred by the data

- Address any intellectual property rights issues (e.g., who holds the rights to these data?)

Part 4: The guidelines, procedures, or policies for data reuse and/or redistribution, attribution, as well as for the creation of derivatives from the data:

- What you will permit in terms of reuse and redistribution of the data, based on policies for access and sharing

- Think about what other researchers (whether in your subject domain or others) may find your data useful

- Identify the lead person or committee on the project who will make the decisions on redistribution on a case-by-case basis

- Where the data will be deposited (e.g., data repository, repository service at your institution, etc.)

Part 5: The measures that will be taken to help ensure the long-term preservation of, and access to, the data - including possible mention of factors such as format migration and who will be responsible for managing the data for the duration of the project:

- Will all of the data produced on your project be preserved, or only some?

- Context for your data (e.g., tools, project documentation, metadata etc.) required to make it accessible and understandable

- Anticipated transformations of the data in order to deposit it and make it available

- The length of time the repository will be available to the public and/or maintained (some directorates have a suggested minimum for the time after a project ends or after publication of certain data)

Again, remember: Data management plans submitted with NSF proposals cannot be longer than two pages.

Tools and Other Resources for Data Management Planning

In the years since the NSF and other funding agencies announced the DMP requirement, tools, and other resources have emerged that researchers may find helpful to consult as part of data management planning.

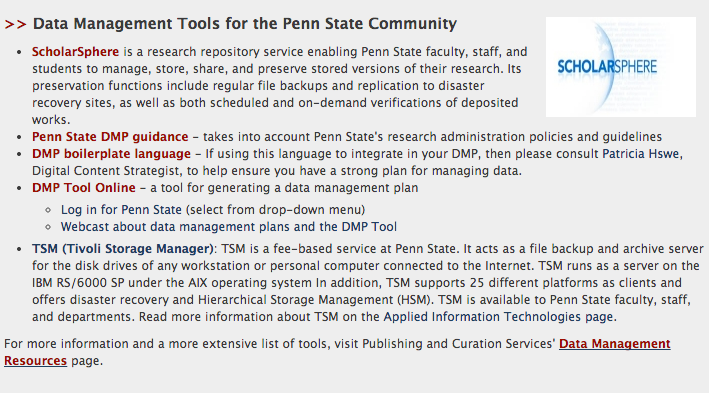

The Penn State University Libraries, in collaboration with the Strategic Interdisciplinary Research Office, have also developed guidance for Penn State researchers that integrates references to the University's research administration policies and guidelines: University Policy Manual [10] and Scholarsphere [11].

Information about additional tools, services, and resources for long-term management of data is available from the Libraries’ research guide on Data Repository Services and Tools [13].

Another valuable resource is the DMPTool [14], available online for any researcher to use. Penn State has an institutional login [15].

With the DMPTool, researchers complete a webform describing their data management plan, which the DMPTool then formats to the specifications required by the NSF or other major granting agency. The resulting plan, which should be proofed by others (such as the liaison librarian for your subject), will be ready to be submitted, along with the proposal, to the grant funding agency.

If you use the DMPTool to develop a DMP, then keep in mind that the DMP generated at the end might not be only two pages - it could exceed the page limit. This means you'll need to do extra work in making sure the content does not exceed two pages.

Summary

Since 2011, funding agencies such as the NSF, the NIH, and the NEH have required that researchers applying for grant funding for their projects also include a data management plan, also known as a DMP - a document that describes how the applicant will manage the research data that are generated for the duration of the project.

There are many reasons why a DMP is necessary:

- A DMP gets researchers thinking about the data lifecycle before they start collecting data. It compels them to consider and plan how they will gather, describe, analyze, preserve, and make accessible and usable their data for other researchers to repurpose or to create derivatives from.

- Data have intrinsic value that others can learn from and build off of. A DMP helps ensure that data will be available for research verification purposes, if not also reproducibility purposes.

- A DMP can help stave off data loss and breaches of data, especially for sensitive or restricted data.

- Research projects funded by federal agencies are projects funded with taxpayer dollars, which means the data should be publicly available. A DMP is intended as additional assurance that such data will be accessible to the public.

Penn State's tools for data management planning include its repository service, ScholarSphere [16]; guidance [11] that integrates Penn State's research administration guidelines and policies for writing a plan; and boilerplate language [17] stating the commitment from the University Libraries and Information Technology Services to preserve and make persistently accessible data sets that are deposited into ScholarSphere. Researchers are welcome to build on the language, in consultation with librarians and technologists at Penn State.

Penn State also has a login for the DMPTool [18], which lets researchers fill in the components of a DMP and, upon completion, then generates a DMP. It is strongly advised that researchers review the resulting DMP to make sure that it does not exceed the two-page limit and that the plan makes sense.

This brief video (4:40) shares a humorous data management and sharing snafu in three short acts:

DR. JUDY BENIGN: Hello! My name is Dr. Judy Benign, I'm an oncologist at NYU School of Medicine.

BROWN BEAR: Hello, Dr. Judy Benign!

DR. JUDY BENIGN: I read your article on B-cell function. I think that I could use the data for my work on pancreatic cancer.

BROWN BEAR: I am not an oncologist!

DR. JUDY BENIGN: I know but I think I could use the data for my work on pancreatic cancer. Do you have the data?

BROWN BEAR: Everything you need to know is in the article!

DR. JUDY BENIGN: No. What I need is the data! Will you share your data?

BROWN BEAR: I am not sure that will be possible.

DR. JUDY BENIGN: But your work is in PubMed Central and was funded by NIH.

BROWN BEAR: That is true!

DR. JUDY BENIGN: ... and it was published in Science which requires that you share your data.

BROWN BEAR: I did publish in Science.

DR. JUDY BENIGN: Then I am requesting your data! Can I have a copy of your data?

BROWN BEAR: I am not sure where my data is!

DR. JUDY BENIGN:But surely you saved your data!

BROWN BEAR: I did, I saved it on a USB drive!

DR. JUDY BENIGN: Where is the USB drive?

BROWN BEAR: It is in a box... ... it is in a box at home... I just moved!

DR. JUDY BENIGN: but can I use your data?

BROWN BEAR: There are many boxes! So many boxes! I forgot to label the boxes.

[ON SCREEN TEXT: 7 months later]

DR. JUDY BENIGN: Hello again! Thank you for sending me a copy of your data on a USB drive, I received the envelope yesterday.

BROWN BEAR: You are welcome, but I will need that back when you are finished, that is my only copy!

DR. JUDY BENIGN:I did have a question.

BROWN BEAR: What is your question? You might find the answer in my article!

DR. JUDY BENIGN:No. I received the data, but when I opened it up it was in hexadecimal.

BROWN BEAR: Yes - that is right!

DR. JUDY BENIGN: I cannot read hexadecimal!

BROWN BEAR: You asked for my data and I gave it to you. I have done what you asked.

DR. JUDY BENIGN: But is there a way to read the hexadecimal?

BROWN BEAR: You will need the program that created the hexadecimal file!

DR. JUDY BENIGN: Yes, I will. What is the name of the program?

BROWN BEAR: "Cytosynth"

DR. JUDY BENIGN: I do not know this program.

BROWN BEAR: It was a very good program! The company that made it went bankrupt in 2007!

DR. JUDY BENIGN: Do you have a copy of the program?

BROWN BEAR: I do not use this program any more because the company that made it when a bankrupt. Maybe you can buy a copy on eBay?

[ON SCREEN TEXT: 20 minutes later...]

DR. JUDY BENIGN: I have good news!

BROWN BEAR: You again!

DR. JUDY BENIGN: I talked to my colleague... she knew a person with a copy of the software!

BROWN BEAR: Then why do you need me? Everything you need to know about the data is in the article!

DR. JUDY BENIGN:I opened the data and I could not understand it!

BROWN BEAR: If you have the program you will find it is clear!

DR. JUDY BENIGN: Well... I noticed that you called your data fields "Sam"... Is that an abbreviation?

BROWN BEAR: Yes! It is an abbreviation of my co-author's name... His name is Samuel Lee, we call him "Sam".

DR. JUDY BENIGN: I see... and what is the content of the field called "Sam1"?

BROWN BEAR: Ah yes... "Sam1 is the level of CXCR4 expression.

DR. JUDY BENIGN: and what is the content of the field called "Sam2"?

BROWN BEAR: That is logical if you think about it!

DR. JUDY BENIGN: What is the content of the field called "Sam2"?

BROWN BEAR: I don't remember!

DR. JUDY BENIGN: what about "Sam3"?

DR. JUDY BENIGN: Is there a guide to the data anywhere?

BROWN BEAR: Yes, of course!

It is the article that is published in Science!

DR. JUDY BENIGN: The article does not tell me what the field names mean. Is there any record of what these field names mean?

BROWN BEAR: Yes! My co-author knows what the content of Sam2 is... and Sam3... and Sam4

DR. JUDY BENIGN: Can I talk to your co-author?

BROWN BEAR: I am not sure!

DR. JUDY BENIGN: I would very much like to talk to you co-author.

BROWN BEAR: Well, he was a graduate student. He went back to China 2 years ago.

DR. JUDY BENIGN: Can I have his contact information?

BROWN BEAR: He is in China... his name is "Sam Lee".

DR. JUDY BENIGN: I think I cannot use your data.

BROWN BEAR: You could check the article... to see if what you need is there!

DR. JUDY BENIGN: Please stop talking now!

Check Your Understanding

Why do researchers need a DMP?

(a) It is required by funding agencies.

(b) Having a plan helps ensure data sharing and access.

(c) Replicability of research results depends a lot on good management of data.

(d) All of the above.

Click for answer.

Click for answer.ANSWER: (d) All of the above. The key funding agencies, such as the NSF, NIH, and NEH, are requiring DMPs to foster increased sharing of, and thus access to, research data. Since federal tax dollars fund such projects, the public has a right to have access to the data generated by them. Having a plan for managing data through their lifecycle also aids in the reproducibility of science.

Part 1: Data and Data Collection

Dr. Smart Asks Kim to Write a DMP

A new graduate student, Kim, has just come on board Professor I. B. Smart's research team. For Kim's first assignment, Dr. Smart has asked her to prepare the data management plan for a grant proposal he is writing. He has gathered initial data and asked Kim to look at them to determine what's been collected and how to begin describing the data. Kim's assessment will help both her and Dr. Smart understand the data types and formats the proposed project will address.

In this part, you will be able to describe the types of data that will be collected during your research, with attention to the following:

- Method of data collection

- Approximate quantity (also growth rate and rate of change) of data

- Tools or software needed to produce, process, and analyze (also visualize, if applicable) the data

1.1 Method of Data Collection

In this part of the DMP, provide a brief statement on your research methodology, addressing the goals of data collection and how you will collect your data. This is also where you may discuss the design of the research project and integrate any information about, or references to, secondary data - perhaps data generated previously for a different project that might impact or influence this one.

For example, do you plan to conduct a survey or interviews, use observational or experimental techniques? You will need to describe each in enough detail that the reader can understand your plan as well as judge the appropriateness of the technique. If you plan to utilize existing data, you will describe the source.

1.2 Data Types

Along with describing your method of data gathering, you will need to state the types of data the project is likely to produce.

Occasionally, grant funding agencies provide guidelines on types of data to document. If you are applying for an NSF grant, then check to see if the directorate overseeing the grant program offers any guidance on data types to be documented.

Research data comes in many flavors and may be classified or categorized as the following (from the U. Edinburgh, “Defining research data” (pp. 5-6), in Edinburgh University Data Library Research Data Management Handbook [22]):

- sample or specimen data

- observational (e.g., sensor data, data from surveys)

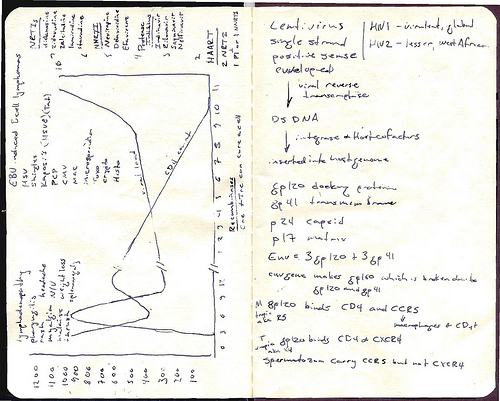

- experimental (e.g., gene sequencing data)

- simulation (e.g., climate modeling data)

- derived or compiled (e.g., text mining, 3D models)

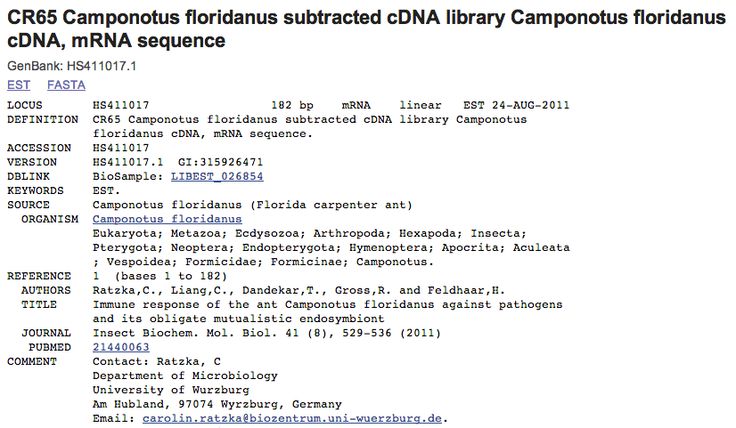

- reference or canonical (e.g., static, peer-reviewed data sets, likely published or curated, such as gene sequence databanks or chemical structures)

While certain kinds of data can withstand benign neglect, most digital data requires a more active approach for preservation as described by Ben Goldman, Digital Archivist at the Penn State University Libraries.

1.3 Data Formats

In addition to documenting the types of data likely to be collected, a DMP also describes the format(s) the data are likely to take. Experienced researchers are familiar with how frequently formats and storage devices change. Dr. Stephenson describes his experience in the following video.

The formats that research data can take include, but are not necessarily limited to, the following (from the U. Edinburgh, “Defining research data” (pp. 5-6), in Edinburgh University Data Library Research Data Management Handbook [22]):

- Text files - MS Word docs, .txt files, PDF, RTF, XML (Extensible Markup Language)

- Numerical - SPSS, Stata, Excel

- Multimedia - jpg / jpeg, gif, tiff, png, mpeg, mp4, QuickTime

- Models - 3D, statistical

- Software - Java, C, Python

- Discipline specific formats - Flexible Image Transport System (FITS) in astronomy, Crystallographic Information File (CIF) for crystallography

- Instrument specific formats - Olympus Confocal Microscope Data Format, Carl Zeiss

- Specimen collections

Other factors to consider when thinking about data formats include whether the format is proprietary or is an open, community-supported standard. Some formats that are proprietary, such as .docx and .xlsx, are widely used, that it is likely they will be around for a long time, thus avoiding format obsolescence.

The use of formats that are open, well-documented standards with robust usage by researchers helps ensure that your data will be accessible over the long term (from “File Formats for Long-Term Access,” [25] at MIT’s Data Management and Publishing site). Ben Goldman describes some resources available to help researchers select appropriate formats in the following video.

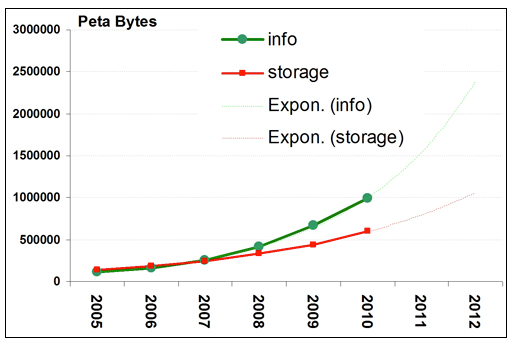

1.4 Data Quantity and Rate of Growth

If possible, a DMP should estimate how much data is expected to be generated and the rate at which it will likely grow. Such an approximation will also inform storage capacity and other related needs.

Some questions to consider, if data collection has already started, are the following:

- Where and how are the data currently stored?

- How long has data collection been occurring?

- During this period, how much data has been collected or generated?

- How much storage capacity is the collected data using?

- How frequently have you needed to access the data?

If a specialized storage facility or capability will be required, it should be described in this section. This is more common for collections of non-digital resources such as physical samples, but may be helpful to address with other data types as well.

1.5 Tools or Software to Interpret and Manipulate Data

In addition to describing data types, formats, and quantity, provide a statement about any tools you will use in order to produce, process, and/or analyze the data. Include any tools that the project is likely to leverage for visualization or display of the data. Also, mention any additional materials that will be provided in order to help others who are interested in using your data to understand them.

It is always helpful to describe the software and version used to record your data, if in digital form. In the video below, Ben Goldman describes some of the challenges digital archivists face related to dealing with obsolete software formats.

Examples of tools and software used to interpret and manipulate data:

- Spreadsheet software such as Excel

- Visualization software

- Mapping software such as ArcGIS

- Statistical programs such as SAS, SPSS and Minitab

- Survey software such as REDCap, ....

- Hardware for data capture such as digital cameras, scanners, telescopes...

- Measurement devices such as calorimeters, gauges, scales, thermometers, ...

For any of these tools, it is useful to record the version or model. For example, what software version did you use? What model of scanner? What resolution was used? Other supporting information that might help understand how the data was collected or encoded is useful. For example, knowing that the instrument reported data in metric units, to a particular accuracy, etc. is particularly helpful information for future users of your data. Other types of useful data include codebooks and calibration information.

Click to expand to provide more information

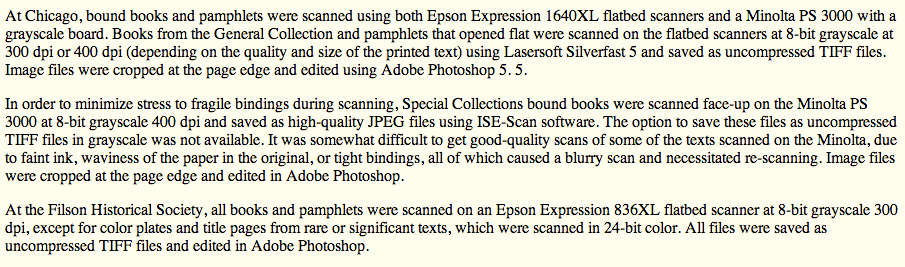

At Chicago, bound books and pamphlets were scanned using both Epson Expression 1640XL flatbed scanners and a Minolta PS 3000 with a grayscale board. Books from the General Collection and pamphlets that opened flat were scanned on the flatbed scanners at 8-bit grayscale at 300 dpi or 400 dpi (depending on the quality and size of the printed text) using Lasersoft Silverfast 5 and saved as uncompressed TIFF files. Image files were cropped at the page edge and edited using Adobe Photoshop 5.5.

In order to minimize stress to fragile bindings during scanning, Special Collections bound books were scanned face-up on the Minolta PS 3000 at 8-bit grayscale 400 dpi and saved as high-quality JPEG files using ISE-Scan software. The option to save these files as uncompressed TIFF files in grayscale was not available. It was somewhat difficult to get good-quality scans of some of the texts scanned on the Minolta, due to faint ink, waviness of the paper in the original, or tight bindings, all of which caused a blurry scan and necessitated re-scanning. Image files were cropped at the page edge and edited in Adobe Photoshop.

At the Filson Historical Society, all books and pamphlets were scanned on an Epson Expression 836XL flatbed scanner at 8-bit grayscale 300 dpi, except for color plates and title pages from rare or significant texts, which were scanned in 24-bit color. All files were saved as uncompressed TIFF files and edited in Adobe Photoshop.

1.6 Summary

Your DMP should describe briefly the research methodology for your project - i.e., how you will collect data for your project and what the goals of such collection will be. Will there be secondary data from a previous or existing project that you'll use? Be sure to integrate any additional information that will help reviewers understand clearly your project and the techniques you'll be implementing.

Be sure to note the types of data you'll be collecting - e.g., specimen, observational, experimental, simulation, derived, etc. The DMP should also state what formats your data will be in - will they be text files, numerical data, modeling data, software code? Use, where possible, open-source (i.e., non-proprietary) formats - or, at the very least, formats in heavy use by your research community. For example, many researchers use Excel to keep track of data they're collecting; though a proprietary format, it's almost ubiquitous usage is providing assurances that it will subsist for some time.

In addition, the DMP should describe the tools or software you'll rely upon to make sense of the data and perform analyses on them.

Finally, in writing about your research methodology and data collection practices in a DMP, try to estimate how fast (or slowly) your data will grow. Where will the data be kept? How much storage is it possible to anticipate to cover the expected rate of data growth? How often will you need to access the data you're collecting? If there are data from an existing project, then it might prove a relevant exercise to revisit data from a previous project and see if the rate of growth could be tracked over a certain period of time.

Check Your Understanding

In each example below, choose the preferred format to ensure accessibility for the long term:

(a) .doc

(b) .txt

Click for answer.

Click for answer.

(a) TIFF

(b) GIF

Click for answer.

Click for answer.

Part 2: Documenting the Data

Kim Learns about Metadata

Kim has now taken stock of Professor Smart's data, noting in appropriate detail its types and formats, as well as documenting the size of it and estimating its rate of growth. Familiarizing herself in this way with the data, she's now ready to think about how to describe what it is and investigate what the community of researchers working with similar data use to describe it. She's heard of “metadata” but is not quite sure what it means or why she might need it.

In this part, you will understand the value of metadata and metadata standards, including the following:

- Determine what metadata are required (what information about your data is important to document?)

- Document how metadata will be recorded (who's going to do it? where? with what frequency?)

- Review directory and file-naming conventions

2.1 What is Metadata?

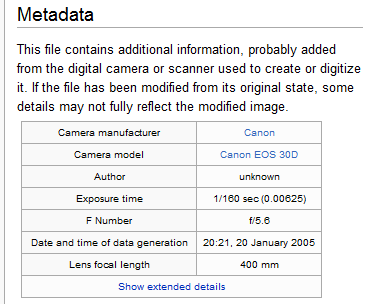

Further documentation and description about your data are needed beyond details about its types and formats. Such description, also known as “metadata,” answers the following questions about your data:

- Who created it?

- What is it?

- When was it created?

- How was it generated?

- Where was it created?

- How may it be used?

- Are there restrictions on it?

Metadata is, literally, “data about data” - meaning, it is information about a resource. Any answers to the above questions would then serve as metadata.

In the context of a DMP, the resource being described and managed is data. In fact, documenting the types and formats of your data, as described earlier, could also be seen as capturing metadata.

Examples of metadata elements that may be used to describe data:

- Title of the project

- Names of researchers involved

- Abstract or summary about the project and the data

- Research topic, or subject of research

- Temporal coverage / information

- Spatial coordinates / Location information

- Instrumentation used

- Access or rights policies/restrictions

- Hardware and/or software used

Metadata also helps organize information about a resource and give it a structure, which enhances search and discovery of data, as well as enables easier access to it.

Your community of interest (research community) may have recommendations as to what kind of metadata to capture. The next section gives some guidance on where to obtain such information.

2.2 The Importance of Standards in Metadata

In documenting your data with metadata, it is important to adhere to standards - standard vocabularies, standard schemas, etc. Organizing your data using a standards-based approach helps ensure interoperability between systems, which also enhances discovery of, and access to, data. To Ben Goldman, metadata is an essential tool for managing collections, and adherence to common standards is vital to making the data reusable. He shares some of his experiences with trying to decipher old data in the video below.

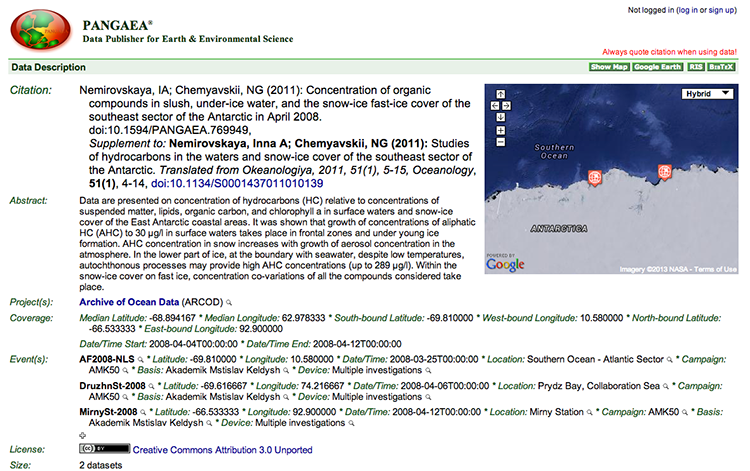

One common standard or schema followed in many repositories is the Dublin Core Metadata Element Set [35], which has 15 metadata fields (e.g., creator, title, subject, rights, description, etc.). Your research community may already have metadata standards that it follows. A useful list of disciplinary standards to consult is at the Digital Curation Centre (DCC) [36]website. Another way to find out more about metadata standards for your research data is to consult the data repositories that your data might be suitable for. Two registries of repositories, in particular, are worthwhile checking out:

- DataBib [37] is searchable catalog / registry / directory /bibliography of research data repositories.”

- DataCite Repositories List [38] - Working document listing data repositories.

You might also consult the metadata librarian at your institution's library to find out more about what standards to apply to your data. Ultimately, an exploration of these standards can provide insight into what kind of information about your data is important to document.

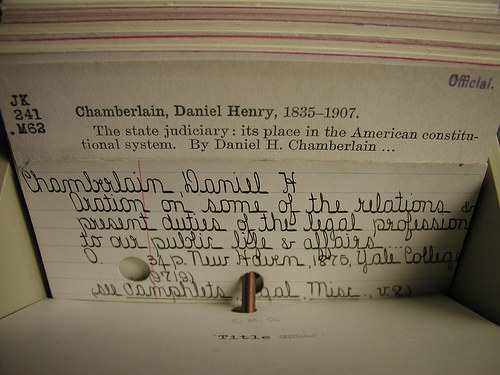

Dr. Alfred Traverse, Curator of the Penn State Herbarium, has extensive experience in managing large of collections of specimens with varying levels of metadata. In the video below, he describes two specimens from the Herbarium's collection, how they were preserved, and their recorded metadata. It is a good illustration of how metadata standards change over time. Standards evolve much as data collection practices do.

2.3 Recording the Metadata

Additional information you may wish to include in a DMP is a brief statement on who will be responsible for recording metadata and having oversight of it, as well as how metadata will be recorded (e.g., in a spreadsheet, or through some other means - perhaps automated).

At the Herbarium, Dr. Traverse copes daily with challenges related to file names and limitations on how the metadata for the specimens was and is recorded. In the following video, he describes some of these challenges as well as how advancements in science can also impact metadata.

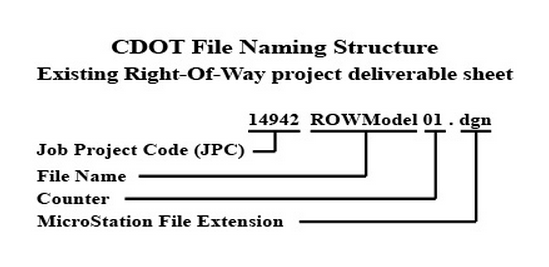

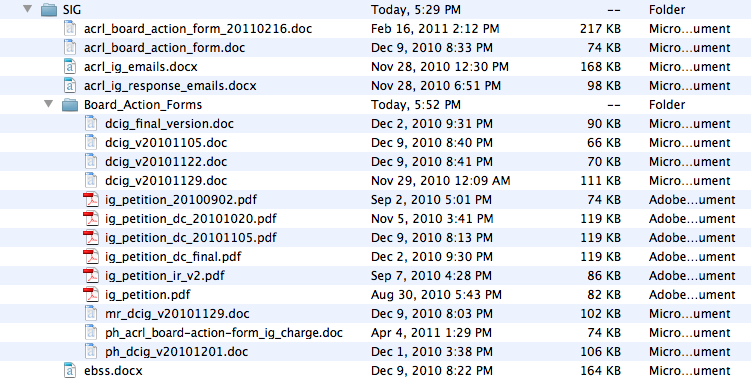

One aspect of recording or documenting metadata is the creation of file names - particularly since data is often kept in file directory systems. Think, for example, of the files you maintain in a hard drive, where files are kept in folders, which are part of a hierarchical structure, or directory, in that drive.

Although file-naming conventions do not have to be discussed in a DMP, it is a key part of data management planning in your local context. When naming your files, think about using descriptive labels that have meaning to others besides yourself, especially if these are data files to be shared with a team. Besides being descriptive, file names should follow a pattern. For example, when including a date and/or year, make sure it follows a pattern like YYYYMMDD. Think about coming up with models for file names - e.g.: project-name_content-of-file_date.file-format. File names should also reflect the version of the file. Versioning helps track the history and progress of data collection and is crucial to collaboration when more than one person needs access to a data file at any given time.

Other file-naming tips:

- Do not use spaces in file names

- Do not use uncommon characters (e.g., #, ?, &, !, etc.)

- Stay within a limit of 32 characters (the more concise yet descriptive, the better)

2.4 Summary

In this part, you learned the meaning of "metadata" and its important role in the documentation of data. In the DMP, in addition to noting types and formats the data will take, consider providing examples of the information you will capture about your data (e.g., information about location, instrumentation, rights and access, etc.). Consult resources such as the Digital Curation Centre's disciplinary standards list [42] to find out what standards for describing data your research community follows.

One common metadata schema that is discipline agnostic is the Dublin Core metadata element set. It's strongly advised to consult a metadata librarian, who can assist you in data description. A metadata librarian can also provide guidance on approaches to recording metadata, such as how to name files. A detail such as file naming convention is not necessary to include in a DMP, but you and your project team should decide as early as possible what conventions the team will follow for naming files.

Another resource worthwhile checking out are data repository indexes, such as DataBib [37], which you can use to find a repository suitable for your data when your project is ready to deposit them. Seeking out an appropriate repository ahead of time and learning about its requirements can inform how you describe your data.

Check Your Understanding

You are collecting survey data and have a field in your data set for geographic location. Some of your responses include both city and state; others include only the country; some did not respond at all. You've developed a codebook to describe how you've chosen to record this and other data from your survey. Is it appropriate to include the codebook in your metadata?

(a) Yes

(b) No

Click for answer.

Click for answer.ANSWER: (a) Yes. Codebooks are considered part of the metadata, since they document and describe aspects of the data you have collected. Without a codebook, users of your data, such as other researchers, will not be able to understand your data readily, or at all, making reuse of the data and the ability to build on it highly unlikely. So, if you have developed a codebook as part of documenting your research data, then by all means include it as part of the metadata for your data.

Part 3: Policies for Data Sharing and Access

Kim Addresses Issues of Data Access and Restrictions

Having explored data repositories for their metadata requirements and studied the disciplinary standards offered by organizations such as the Digital Curation Center in the U.K., Kim has begun work on applying metadata standards for documenting Dr. Smart's data. Dr. Smart has also informed Kim that he intends to make the data publicly available. He instructs Kim to make certain there are no issues that would prevent broad sharing. Kim will be seeking guidance on the issues and questions that pertain to sharing and access to ensure that management of this research data does not create security or confidentiality breaches, or impinge on any intellectual property rights.

In this part, you will learn about the importance of providing safeguards for protection of confidential information and requirements for restricting data. You will also consider how and when access to your data will be provided, and to whom. We also touch on the importance of data citation.

3.1 Access and Availability of Data

A major reason why federal funding agencies require DMPs is to encourage researchers to think as early in the project as possible about how and when data will be shared and made available. Funding agencies expect you to be clear in the DMP about your approach or policy for sharing and giving access to your data. Sharing also makes possible reuses and repurposing of data, as explained later in this tutorial.

Ways of sharing data can vary. They depend on the research domain, on the availability of services, on the size of the data set, and other factors. Many of these are covered later in this tutorial in the section which addresses long-term preservation of data. Preserving data ensures long-term access to it. What you want to make sure your DMP states is that you will deposit your data in a repository - whether it's a repository dedicated to data from your research domain or an institutional repository that accepts data sets. Penn State has such a repository - ScholarSphere [16], about which you may learn more here [44], in the tutorial.

You should note in the DMP when data will be made available - i.e., during the project, or afterward? Will there be any embargoes? If so, why and for how long? Will data be shared indefinitely, or will there be temporal constraints?

Will all the data be shared, or only a portion? Have you adequately addressed levels of access, e.g., who is allowed to use the data, etc.? (You may already have addressed this in the section of the plan related to data access.)

Click to expand to provide more information

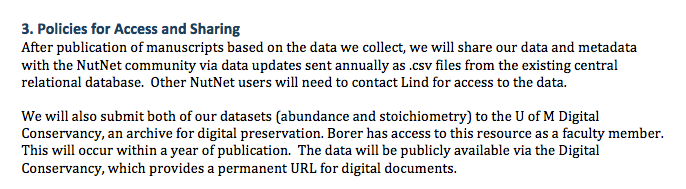

3. Policies for Access and Sharing

After publication of manuscripts based on the data we collect, we will share our data and metadata with the NutNet community via data updates sent annually as .csv files from the existing central relational database. Other NutNet users will need to contact Lind for access to the data.

We will also submit both of our datasets (abundance and stoichiometry) to the U of M Digital Conservancy, an archive for digital preservaton. Borer has access to this resource as a faculty member. This will occur within a year of publication. The data will be publicly available via the Digital Conservancy, which provides a permanent URL for digital documents.

In DMPs, researchers often state that their findings will be published as articles and other genres relevant to their particular disciplines. Increasingly, publications are linking to data sets that have been deposited into repositories; this is another reason why depositing your data into repositories is important.

The NSF and other funding agencies that require DMPs now frown on the previously common practice of sharing data sets upon request, such as via email. Researchers' email addresses are not permanent, for one thing, and on-demand access unnecessarily burdens the researcher with the redundant act of locating and attaching, or pointing to, the requested data set. By submitting the data set to a repository, data become publicly discoverable, findable, and accessible.

While typically not mentioned in the DMP, the citation of data marks another method of sharing data and attributing the researchers who created them. The organization DataCite [46] has examples of citing data [47]. The most crucial component of such a citation is a Digital Object Identifier or DOI [48]. DOIs are assigned to ensure persistent access. Even though the digital object may undergo changes over time, the DOI stays the same.

Another benefit to researchers of having your data made available in a repository is that it becomes more widely accessible and citable. Citation of data is increasingly required by editors and having a permanent URL or repository identifier helps others find your data, as Andrew Stephenson describes in the following video:

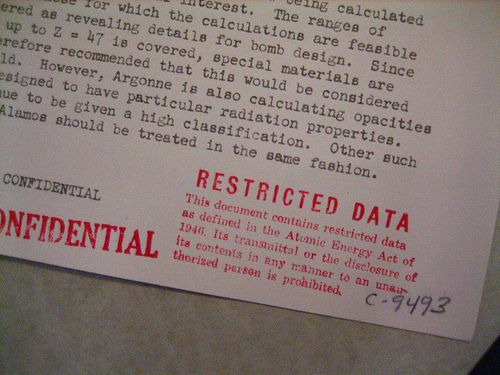

Making publicly funded data available is a common good, however, there are instances where it is important to restrict data. Thus, in a DMP researchers should note what data will be shared and whether there are any restrictions to sharing.

3.2 Confidentiality and Ethics Issues

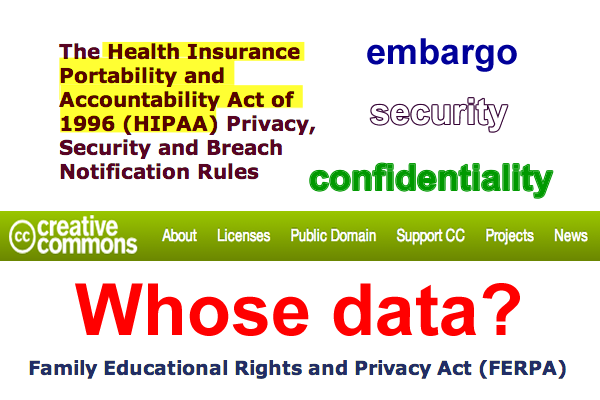

Confidential data usually includes personally identifiable information (PII), such as names, addresses, and Social Security numbers - anything that might point to the identity of a person. Health information data, for example, is protected under the Health Information Privacy and Accountability Act (HIPAA), because it is considered private data.

Data collection stemming from human participant research - such as survey data - and thus requiring approval from an Institutional Review Board, or IRB, typically produces confidential data, access to which must be restricted because of PII. Sharing such data would be a violation of both research ethics and human subjects' privacy.

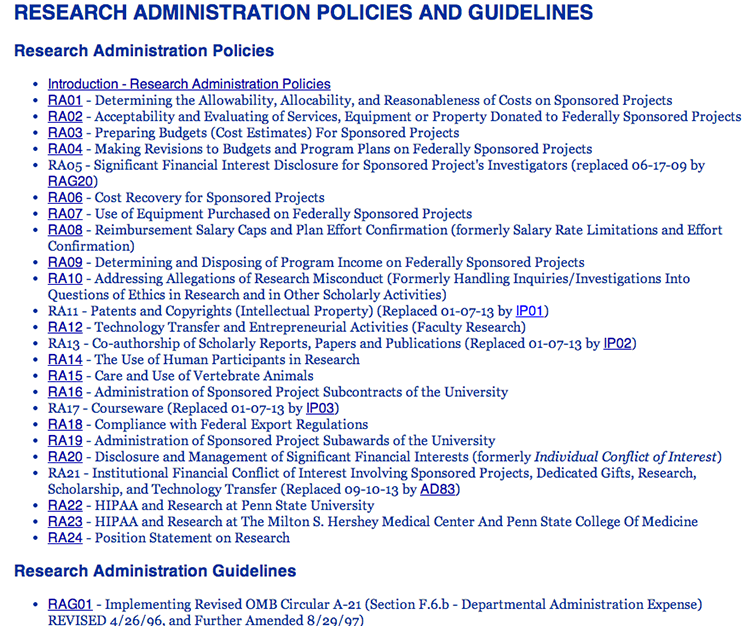

If your research data encompasses any of the above ethics and confidentiality concerns, then you should note these in the DMP. If your project will be generating survey data, then you should also state an intention to comply with Penn State's IRB requirements set by research administration guidelines and policies. Consult Penn State's Human Subjects Research (IRB) site [52]. Review RA 22: HIPAA and Research at Penn State University [53], or, if applicable, RA 23: HIPAA and the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center and Penn State College of Medicine [54].

3.3 Intellectual Property, Embargoes, and Protections

One way to help ensure that confidential data, or data related to patented research, for example, is not shared prematurely is to implement an embargo. Embargoes are intended to bar data sharing and access for a limited period of time, thus protecting the data and the intellectual property rights of the researchers. Typically renewable, an embargo allows the researcher to decide when data may be released. The DMP should state whether an embargo will be imposed on the collected data or not.

Most universities provide guidance and policies on intellectual property rights for research. Penn State does at the General University Reference Utility (GURU) site [57]. It advises on ownership and management of intellectual property (Policy IP01 - Ownership and Management of Intellectual Property [58]), as well as guidance on the intellectual property rights of students (Guideline IPG01 - Faculty Guidance on Student Intellectual Property Rights [59]), and (Guideline IPG02 - Special Student Intellectual Property Agreement Forms [60]),While a DMP does not ordinarily contain this depth of information, it is a recommended practice for researchers to review their institutions’ policies and guidelines on intellectual property rights.

In IRB-approved research, an informed consent agreement between the researcher and the study participants is de rigeur. Depending on the nature and sensitivity of the data, however, researchers may wish to consider including an option in the consent form that allows data sharing. Refer to the guidance provided by the UK Data Archive [62] on informed consent forms, as suggested by the MIT Libraries [63].

Finally, in this section of the proposal, where data protections, sharing, and access are discussed, it's important to state outright who on the project will be responsible for monitoring embargoes, consent forms, and non-disclosure/confidentiality agreements. A key part of managing research data is being explicit about who will adopt what role in such management.

Archivists receive formal training related to these issues. Ben Goldman shares some of his expertise regarding security and access to digital data in the video below.

3.4 Summary

While funding agencies created the DMP requirement to encourage sharing of data, there are data produced on funded research projects that are sensitive and need to be restricted for access and use. These kinds of data tend to include personally identifying information (PII), such as might be collected as the result of demographic surveys or those found in health records. Often such data are protected under federal law, such as the Health Information Privacy and Accountability Act (HIPAA) [51].

If the data resulting from your project are likely to have confidentiality or ethics issues (such as human subject research engenders), then these should be noted in your DMP. Be sure to consult Penn State's Human Subject Research (IRB) site, as well as RA22: HIPAA and Research at Penn State University [53]. If applicable, review RA 23: HIPAA and the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center and Penn State College of Medicine [54].

There can be intellectual property rights issues as well, particularly with patent-pending research, that can prevent the sharing of data for a period of time. In such situations, an embargo may need to be implemented for your data, and you should state such in your DMP, specifying when the embargo will be lifted.

A DMP does not need to go into detail regarding confidential data and intellectual property rights, beyond stating what kind of restrictions on access are likely. For guidance during a project, Penn State provides faculty, students, and staff with research guidelines and policies [61] that can be helpful to draw on.

Finally, if possible, the DMP should state whose role it will be to monitor embargoes, consent forms, non-disclosure/confidentiality agreements, and so on.

Check Your Understanding

Which of the following types of data would be considered confidential?

(a) Social Security numbers

(b) Student grades

(c) Personal medical information

(d) All of the above

Click for answer.

Click for answer.ANSWER: (d) All of the above. Confidential information is often information that might lead to the identification of the human subject or to more information about the human subject who participated in a study. Special measures, such as redaction or anonymization, are typically taken to prevent breaches of confidence.

Part 4: Reuse and Redistribution of Data

Kim Considers Ways that the Data May Be Repurposed

Kim now has a good sense of how much of Dr. Smart's data can be shared without restrictions, and how much of it will need extended protections. She's presently at the point of investigating another aspect of data sharing and access - the means of distributing the data for reuse and creation of derivatives. Dr. Smart would like to be able to point to his data sets from this research, making them freely available, rather than have to provide them on demand. He's interested in making his data easily discoverable and easily accessible.

In this part, you will find out some of the ways to make research data available for sharing and reuse, such as modes and levels of access.

4.1 Benefits of Sharing Data

Earlier you learned about restrictions on data, especially if the data being collected are sensitive or confidential in any way, as well as about intellectual property rights that can be associated with data.

In a DMP researchers also need to state how they will share and make accessible data that are not restricted. Public access to data marks a central motivation behind the DMP requirement. As stated previously, data that have been generated by a federally funded project is publicly funded data - that is, data made possible by taxpayer dollars. Data sharing is also integral to the responsible conduct of research; it contributes to the verifiability of research results.Thus, in this part of a DMP, you describe how you will make your data available for sharing and reuse.

Using his own lab as an example, in the following video Andrew Stephenson explains some of the reasons why granting agencies, such as NSF, have decided to consider the data from funded research to be public data.

4.2 How Will the Data Be Shared?

In thinking about how your data will be disseminated and shared, consider the primary community (or communities) of interest for your research - that is, who is the anticipated audience for your data?

Another factor to address is how the data in your field are currently shared. Are there well-known data repositories through which data of the type you'll be generating are typically made accessible? Before the DMP requirement was implemented, it was acceptable for researchers to make assurances in grant applications that their data would be stored on a hard drive and be made data available upon request. Since the mandate, it is recommended that you make your data publicly available via a repository service. (The next part of this tutorial will focus more on data repositories.)

Intended and future uses:

Finally, the DMP should state what the intended uses of the data are likely to be, and who is likely to use the data. How might the data be reused and repurposed and thus transformed? What alternative uses of the collected data might be possible? As described by Dr. Traverse in the following video, it may not even be possible for you to imagine some of the future uses for your data!

4.3 Summary

The DMP should describe how the project will share data, making them publicly available (unless the data are restricted) for broad access and sharing. Providing access to data is responsible science and helps ensure verifiability of the research results.

It is worthwhile thinking how data in your field are typically shared and accessed. Perhaps there are certain data repositories that hold data sets in your field that you and your lab team frequently consult. Increasingly, the practice for researchers is not to keep their data on a hard drive and distribute it on request but to deposit them to a repository, linking to them from publications and laboratory websites, so that they can be discoverable and findable.

The DMP also typically states when the data will be made available, whether during the project or after it. If embargoes will be implemented, then this fact needs to be surfaced as well, with accompanying information about any time constraints. Similarly, will all the data be shared, or only some of them? If the DMP hasn't addressed levels of access (e.g., who is permitted access to the data), then this is where that information should be given, too.

Check Your Understanding

True or False: The current best practice for data sharing is to state in your DMP that your research data is available upon request.

(a) True

(b) False

Click for answer.

Click for answer.ANSWER: (b) False. Increasingly, funding agencies wish to see in DMPs that researchers will share their data via data repositories, or an institution-wide repository service like Penn State’s ScholarSphere. By depositing data into a repository service, the onus is removed from the researcher in making sure the data are preserved over the long term and thus accessible on an ongoing basis. This way, researchers can post the permanent link or URL or DOI for the data set to the project website and be assured the data set will continue to be accessible.

Part 5: Long-Term Preservation and Archiving of Data

Kim Learns about Data Preservation and Access

Kim has come a long way in her understanding of data management planning. In the previous parts of this tutorial, she learned how to document data and about the importance of using standards in such documentation and description. She now appreciates the need to be clear in the DMP about how the data will be shared and made accessible, and what the time frame will be for making them available. Kim has also been discussing with Dr. Smart what kinds of derivatives from the data might be possible and interesting for related research communities. She is now in a position to finish the DMP by addressing storage and preservation of Dr. Smart's data.

Part 5 of this tutorial guides you through the process of where to store your data, once your project concludes, so that you may be assured of long-term preservation of the data for ongoing access. You'll be able to address the following in this part of the DMP:

-

Disciplinary data repositories that are applicable to the research data sets you will be collecting and sharing. (Note: some repositories have requirements in terms of types of data, descriptive standards, and size of data.)

-

Information about Penn State's repository service, ScholarSphere [16], where researchers have deposited data to share them and ensure persistent access to them.

-

Tips on how to store your data for safekeeping.

5.1 Issues Regarding Long-Term Access

As you consider where to deposit your data, think about, as well, how long you will make your data available and accessible, after your project ends. In addition, how much of your data will you make available? All of it - from the raw files to the processed outputs? How often will you need to access it? How will you enable other users to make use of it, particularly if the use of the data requires the application of other tools or systems?

Ben Goldman discusses some of the challenges and resources available to the preservation of digital data.

5.2 Data Repositories

As mentioned earlier, there may be data repositories suitable for the data that your project will produce. To find such repositories, you may wish to consult Databib [37] - a growing list of repositories for research data primarily in the sciences and social sciences. Data sets stored in a disciplinary repository have some advantages, including a greater likelihood of discovery by other researchers. Another benefit to researchers in having your data made available in a repository is that it is more widely accessible and citable. Andrew Stephenson attests to the advantages of data repositories in the following video.

Examples of disciplinary data repositories:

- Dryad [71] - for data sets in the applied biological sciences that are linked to published articles

- ChemxSeer [72] - for chemistry data sets

- ESA (Ecological Society of America) Data Registry [73] - for data sets in ecology

- ICPSR (Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research) [74] - for social sciences data

- IEDA (Integrated Earth Data Applications) [75] - for “observational solid earth data from the Ocean, Earth, and Polar Sciences”

For help in selecting the appropriate data repository for your data, consult the Libraries’ Data Management mailing list, l-data-mgmt@lists.psu.edu [76].

5.3 Penn State's Repository Service, ScholarSphere

Sometimes, there is not a disciplinary repository for your data, or if there is, then it may have requirements for data set deposits that your data cannot meet - such as requirements in size, format, documentation, etc. In such a case, consider depositing your data to ScholarSphere [16], Penn State's institutional repository. ScholarSphere takes any file format, and there is no maximum amount of data that users can deposit (although there are upload maximums because deposit occurs via the Web).

As Andrew Stephenson describes it, ScholarSphere is a time saver as well.

ScholarSphere is a self-deposit repository service ensuring the long-time preservation of data for ongoing access. No registration or creation of an account is necessary. The service is available to anyone in the Penn State community to use - all that is required is a current Web Access ID.

To learn more about ScholarSphere, visit its Help page [78].

5.4 Taking a Distributed Approach to Data Storage

Depositing your data to a formal repository such as those mentioned in the previous section is a good practice for research projects.

However, preserving your data and making them accessible in only one place is not enough. A distributed approach to storing your data is highly recommended. By being part of a campus community, a researcher has options beyond local storage of her data. One should investigate options beyond campus as well. This is something librarians and archivists can help with, as described in the video below.

Below are ways you can distribute storage of your data (based on U. Minnesota Libraries' "Storing Data Securely [80],".):

- Local options - easy to access your data and control access, but you are responsible for backing up that data,

- Internal hard drive (computer hard drive)

- External hard drives - extensive storage capacity is increasingly inexpensive to purchase

- College or departmental servers, local networks

- Campus-based options - some at no cost, others for a fee; facilitates collaboration; users have less control.

- Penn State Access Accounts Storage Space (PASS) [81] - administered by Information Technology Services (ITS), requires a Web Access Account ID; 500 MB to start, can be increased to 10GB.

- Tivoli Storage Manager (TSM) [82] - administered by Applied Information Technologies in ITS, fee-based file backup service

- High-Performance Computing [83] - administered by Research Computing and Cyberinfrastructure [84] in ITS, fee-based.

- Cloud-based options - someone else takes care of your data and manages it; not recommended for sensitive data, because it's third-party storage.

- Subject-based repositories such as GenBank

- Commercial services such as Amazon Web Services [85]

- Box.com [86], Dropbox [87], ElephantDrive [88], Google Drive [89], Jungle Disk [90], SpiderOak [91]

Quick Tips for Storage and Backup of Data

- Keep at least three copies of your data

- Have “master” or original files from which copies get made

- Put files in external but local storage, such as an external hard drive (but not on optical media)

- Also, put files in external but remote storage, or on remote servers

This way, files are physically (geographically) dispersed for disaster recovery purposes.

5.5 Summary

In the last section of the DMP, be sure to discuss how the project will store and preserve the data. This entails mention not only of any data repositories where the project will deposit data but also how, for the duration of the project, data storage will be handled and managed and kept secure. A distributed approach to data storage is the standard to follow, which includes maintaining at least three copies of data; keeping a "master" file for the sole purpose of making copies, and keeping files both in external hard drives and in external but remote storage or on remote servers.

Data sets deposited into a disciplinary repository have some advantages, including a greater chance of discovery by other researchers in your field because of their familiarity with such a repository. Examples of disciplinary data repositories (more of which can be found in DataBib):

- Dryad- for data sets in the applied biological sciences that are linked to published articles

- ChemxSeer- for chemistry data sets

- ESA (Ecological Society of America) Data Registry- for data sets in ecology

- ICPSR (Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research)- for social sciences data

- IEDA (Integrated Earth Data Applications)- for “observational solid earth data from the Ocean, Earth, and Polar Sciences”

Occasionally, there is not a disciplinary data repository available for your data. In such cases, you should consider depositing your data sets to Penn State's repository service, ScholarSphere, which is a self-deposit service that takes any format and requires no creation of an account. The only requirement for deposit is that you have a current Penn State Web Access ID.

Check Your Understanding

True or False: ScholarSphere is a free service for all Penn State researchers.

(a) True

(b) False

Click for answer.

Click for answer.ANSWER: (a) True. ScholarSphere, Penn State’s repository service for all its faculty, students, and staff does not charge any fees for usage. All that is required is a Penn State Web Access ID. Once you log into ScholarSphere, you automatically become a user (whether you deposit files or not). Currently, there is also no limit to the number of files you may deposit (i.e., no maximum on storage size for deposited files). ScholarSphere takes any file format; it can accommodate web uploads of single files up to 500MB and a folder of files up to 1 GB. Since it has Dropbox integration, files larger than 500MB may be uploaded to ScholarSphere via Dropbox. Finally, while the default access level is open access, users may adjust access to “Penn State only” or to “private.”

Next Steps to Take

Kim Arranges a Consult - and Updates her Resume!

Kim is finished writing the DMP for Dr. Smart's grant proposal application. Her next steps are to ask the librarian responsible for reviewing DMPs with researchers to look it over and provide feedback. She also will contact the liaison/subject librarian for her discipline to seek additional comments on the DMP. Dr. Smart is thrilled with her contribution and tells Kim that now that she has written a DMP, she should list this experience on her resume. Scientists who know how to plan for, and manage, research data will be in high demand!

Essentially, a DMP is a description of how you will collect, manage, document, preserve and share your data. The DMP can save you time and effort down the road. Not only is it required by many funding agencies, a good DMP can also help improve your chances of getting a grant. A data management plan is a useful tool for any researcher.

The last part of this tutorial reviews the main points to remember in writing a DMP.

Key Take-Away Points

A DMP tells how a researcher will keep track of data for future access and preservation during the course of the research project being proposed. If you are applying to the NSF for funding, then consult the website of the directorate or division for the grant program; some NSF directorates and divisions have more focused guidelines for the DMP.

It's highly recommended that you consult with the University Libraries on the DMP; this is so we have knowledge of the project, can plan ahead if necessary, and can review the DMP prior to submission. Email l-data-mgmt@lists.psu.edu [76] and a librarian will get back to you in response to your inquiry.

The following lists what a DMP needs to address:

- The types of data to be collected or produced during the project, and the processes or methodology for doing so

- Discuss what kind of data will be generated (e.g., sample, specimen, observational, simulation, etc.) and how (methods)

- The formats for the data and the standards that will be followed for documenting and describing the data

- Describe what formats the data will take (e.g., text files, numerical, multimedia, software/code, discipline-specific formats, etc.) and what standards will be used (could be a generic standard, such as Dublin Core element set, or could be a standard prescribed by your research community)

- The availability of the data, including information about ways in which the data will be accessed, and whether there are any issues related to privacy and/or intellectual property

- If your project will be generating sensitive data, then special measures need to be taken to restrict access and use; this is similar for data on patent-pending projects

- Confirm whether IRB approval and consent forms are needed; if so, then the DMP should mention these.

- The guidelines, procedures, or policies for data reuse and/or redistribution, attribution, as well as for creation of derivatives from the data

- Just as it's important to restrict data if it is sensitive, it is important to be clear about uses of data when they are shared - are derivatives allowed, for example?

- The measures that will be taken to help ensure the long-term preservation of, and access to, the data- including possible mention of factors such as form

- Ensuring that the data from your project are preserved - and thus made accessible on an ongoing basis - means implementing a distributed approach to storing the data for the duration of the project and depositing your data to a repository (search for a repository relevant to your data in DataBib), for broader sharing.

- In the absence of a disciplinary repository for your data, consider depositing your data to ScholarSphere [16], Penn State's repository service.

Creating a data management plan does not need to take a lot of time and can be very beneficial to you as a researcher. As Dr. Stephenson describes, DMPs are useful in the long run.

Help Getting Started

Contact Information for DMP Consultations & Data Guidance

The University Libraries offer help with data management planning, including a review of DMPs for a grant proposal and guidance on best practices for managing research data. Please use the contact information below to get in touch when you are seeking help:

Data Management List (coordinated by librarians to address DMP review requests): l-data-mgmt@lists.psu.edu [76]

Patricia Hswe, Digital Content Strategist and Head, ScholarSphere User Services: phswe@psu.edu [94] | 814-867-3702

Ways to Get Started

- Contact the librarian who is in your field to start a conversation about data and DMPs - find out by consulting this list [95].

- ExploreScholarSphere [16] as a service for making your data accessible and preserved for the long term.

- Needing a presentation on data management planning or on ScholarSphere? Contact Patricia Hswe, phswe@psu.edu [94].

- Looking for guidance in the context of Penn State's research administration guidelines and policies? You might find this resource [11] helpful.

- The Libraries also provide boilerplate language [17] that you can enhance in accordance to your needs and insert in your DMP. Please let us know if you use it, however, so we can keep track of researcher needs.

- Try out the DMPTool [14] the next time you need to write a data management plan. Remember, you'll still need to review the plan that is generated after you fill in all the parts of the DMP and make sure it isn't more than two pages in total.

- Seeking a disciplinary data repository service through which to share your data? Explore DataBib [37], a curated registry of data repositories.

Thank you!

Thank you for reviewing the DMP tutorial. We welcome suggestions and other feedback.

Please share your thoughts with use at theUniversity Libraries Publishing and Curation Services [96].