The Prize, Chapter 11 Overview

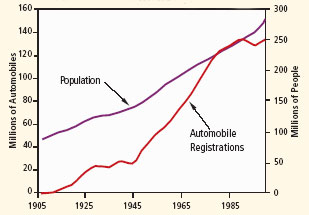

With Chapter 11, we enter “The Age of Gasoline”, arguably an age we are still in it to this day. The demand for gasoline increased and still continues to increase. In 1919, the U.S. used 1.03 million barrels per day; ten years later, demand had increased 2.5 times to 2.58 million barrels per day. The demand of oil for light had transferred to the demand for oil used for mobility. The increase in demand was driven primarily by the increase in the number of automobiles. In 1916, the U.S. had 3.4 million registered vehicles, and by the end of the decade, the number had jumped to 23.1 million, with cars being driven farther and farther. By 1929, nearly 80% of the world’s automobiles were in America, and oil’s share of total energy consumption had gone from 10 to 25% in the decade 1919 -1929, with gasoline and fuel oil accounting for 85% of the total oil consumption.

Figure 4.1 The graph shows national trends in population and automobile registrations in the United States from 1907 through 2000. Both have risen since 1907, but at different rates. Since approximately 1945, automobile registrations have outpaced population growth.

Although we are so used to it that we hardly notice it, a new culture emerged around gasoline, the emergence of the gasoline station. Before 1920, most gasoline was sold by storekeepers, who kept it dangerously in cans in the store. The Automobile Gasoline Company is credited with the first drive-in gas station in St. Louis in 1907. However, the proliferation of gas stations did not catch on until the 1920s. But selling a commodity such as gasoline is tricky. In general, gasoline is gasoline so why would you buy from one instead of another? Price is one way to ensure market share, however you can only reduce price so far before you are losing money. So the oil companies developed trademarks to distinguish themselves and promote competition. The filling/service stations added features that would help their customers with their vehicles by checking/selling tires, batteries, and accessories. Today, we see gas stations and “convenience stores” that sell gasoline. The appearance of the gas station revolutionized how gasoline was marketed.

Chapter 11 discusses the increasing trend we saw in Lesson 3 of oil becoming a key element of national policy and national security. Oil was becoming more of a factor in economic stability and the resilience of the military. As you would expect, with this growing role, also comes controversy and challenges. The Teapot Dome scandal illustrates this aspect in the sense of collusion between private sector companies and government, criminal kickbacks, and political favors. And Teapot Dome itself illustrates another emerging idea, an organized, government-supported reserve to be used for the military. The idea being that the US Navy would have a reliable source of fuel regardless of what was happening geopolitically, and whether imported supplies were threatened.

Today, we are seeing a different challenge associated with such reserves. We have the Strategic Petroleum Reserve created by the government to hold a supply of fuel to be used in times of national emergency. As we will see in this course, when you depend on other countries for oil supply, you tend to be at their mercy in terms of volume, prices, and stability. There has been current controversy around releases from the SPR, including claims that releases are for political reasons- to stabilize fuel prices. Some argue this is not the intended use of the SPR, and is putting national security at risk.

We remember from prior lessons the idea of “Rule of Capture.” A nice way of saying “grab all you can get as fast as you can”. This mentality compromised the efficiency of oil fields, resulting in lost reserves and price volatility. The industry was realizing that this approach clearly does not work in the long run. Enter the concept of “unitization” where producers work together in developing a field to ensure that it is managed as efficiently as possible. A good analogy is a children’s Easter egg hunt. There are two ways to do it- you let all the children run out in the field and grab as much as they can (Rule of Capture), or you establish some rules such as a maximum number of eggs allowed per child, separate areas for age groups, and so on (Unitization). As you can imagine, and as the companies learned, unitization makes sense if those involved agree to cooperate.

New discoveries were few in the years 1917-1920, resulting in pessimism about production and increased prices. For example, Oklahoma crude that sold for $1.20 a barrel in 1916 was selling for $3.36 in 1920. In the 1920s, technology for finding oil improved as geophysicists led the way in developing tools for oil exploration. So, in spite of the shortage fear, the new innovations helped in the discovery of several major fields including the Signal Hill and others which made California the number one oil-producing state in 1923; the Greater Seminole field in Oklahoma in 1926 (flowed at 527,000 barrels per day (BPD) on July 30, 1927) and the Yates field in West Texas and New Mexico.

In addition to innovations in exploration and production, innovations in crude processing/refining such as cracking enabled more and superior gasoline with better anti-knock properties to be extracted out of a barrel of crude, reducing the demand for more crude. With demand decreasing and the many producers each maximizing their production, the flush production led to oversupply and devastating consequences on the price of oil. With the glut and low prices, the opinion of the oil industry began to lean toward an approach of conservation and production control. This time, not based on shortage, but as a means to prevent the flood and its catastrophic effect on pricing. Still, opposition to direct government regulation or involvement was extremely strong.

Restructuring and the Deep Depression

Rockefeller actually set the example of confronting imbalances in supply and demand through consolidation and integration within Standard Oil and the oil industry years before. Consolidation – implies the acquisition of competitors and complementary companies, and Integration – implies the fusing of the upstream (exploration and production) and the downstream (refining, transportation, sales, and distribution) under one company working for the same goal.

The oil industry realized that the strategy of restructuring via consolidation and integration has its advantages and would form the foundation for our modern American oil industry. There were now many big companies and several independents by the 1920s, as by 1927 45% of the refined products were controlled by the various “Standard companies” compared to the 80% two decades earlier.

The stock market plunged in October 1929, ushering in the Great Depression that led to many people losing their jobs, savings, and standard of living. There was massive unemployment, poverty, and hardship throughout the nation, ending the constant growth in demand for oil. Just when the country was realizing in autumn 1930 that the stock market crash was not a simple correction but a true economic disaster, as luck would have it, the largest oil field in the lower 48 states, the Black Giant in East Texas, was discovered. Now, there would be a flood of available petroleum, with a consequent drop in prices.

The Stock Market Crash, just like the COVID outbreak in recent years, are what is called a “Black Swan Event.” Such events are surprises and unexpected, but when viewed in hindsight, should have been expected. The idea is that a black swan is very rare, but genetically it can happen and should be expected to occur at some point. Regardless, Black Swan events are very disruptive to even the best laid plans.

The Prize, Chapter 11 - From Shortage to Surplus: The Age of Gasoline

Sections to Read

- Introduction

- A Century of Travel

- The Magic of Gasoline

- The Tempest in the Teapot

- The Tycoon

- The Rising Tide

Questions to Guide Your Reading:

- What was happening with gasoline in the 1920s?

- What reduced concern about supplies?

- How is oil different from other commodities?

- What is the Rule of Capture and unitization?