Assumptions of Frictionless Exchange

The welfare properties of free exchange

Free exchange among market participants achieves the most-desired allocation of resources from the set of all possible allocations of resources. At the set of prices equating demand and supply in each market, there are no additional exchanges that can increase any one agent's utility without reducing some other agent's utility. The price of apples will settle at the point where I have bought and the orchard has sold exactly the number of apples we want. At that price, I don’t want to buy more, and at that price the orchard does not want to sell more.

In this simplified model, the process of free and voluntary exchange maximizes total social well being, or social welfare. In this context, social welfare does not mean state-funded programs and services to assist disadvantaged groups. In economics, social welfare is simply the well-being of the entire society.

The implicit assumptions

But this welfare result is based on an important, oftentimes implicit, assumption. The model we've described assumes frictionless exchange. To simplify the study of mechanical principles and to make calculations manageable, problems presented to students often begin with “Assume no friction.” Of course, in the real world, we can’t get away with this! Nonetheless, in engineering, this simplifying assumption does allow for a clear and useful study of the underlying principles. In economics, frictionless exchange is the same idea—it is a simplifying assumption that, though useful, leaves out some unavoidable real world forces. Frictionless exchange assumes a market place with no transaction costs.

Examples of transaction costs (exchange frictions, friction costs) are considerations such as fees paid to lawyers and accountants and the time and effort spent shopping and comparing prices -- these are resources that do not provide utility. Nor do they produce other goods that produce utility. Transactions costs refers to resources that are destroyed through the process of exchange. They are the costs incurred in overcoming market imperfections. (In another use, the term “transaction cost” simply means the fee paid to a banker or broker to execute a transaction. This narrower interpretation is not our intended meaning here.)

Transaction costs are a broad group of incurred costs, which can be generally summarized into three groups:

Search and information costs: the costs (resources expended) to determine information about available goods and services. Information such as product availability, price, quality, features and performance, etc.

Bargaining costs: the costs required to reach an agreement with the other party, such as negotiations, documentation and drawing up a contract.

Policing and enforcement costs: the costs of the activities necessary to make sure the other party adheres to the terms of the contract, including legal action (or the threat thereof) when necessary.

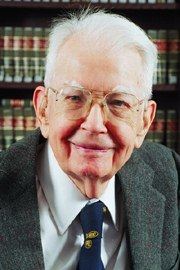

We have Ronald Coase to thank for this added complication to our simple economic models! In fact, transaction costs and all that they imply are so important to economic theory that Professor Coase was awarded the 1991 Nobel Prize in Economics Sciences for this work. For more about the man and his work, including on-going research, visit The Ronald Coase Institute. In his Prize Lecture, Professor Coases talks about making the “essentials of the argument” in a college lecture he gave in 1932 and then goes on to say, “I was then twenty-one years of age and the sun never ceased to shine. I could never have imagined that these ideas would become some 60 years later a major justification for the award of a Nobel Prize. And it is a strange experience to be praised in my eighties for work I did in my twenties.” I love the humanity of his words and the subtle power of his ideas. Thought you’d enjoy them too.