It should be no surprise that there are competing views of geospatial analysis. One school is that intuition, experience, and subjective judgment are key. Analysis here is an art, and non-quantitative methods predominate. Another school is that quantitative data and analysis using such tools as GIS are most relevant. Intelligence analysis here is science-like, and quantitative methods as applied in spatial analysis predominate. This controversy somewhat mirrors a long-standing debate in the intelligence community: if good analysis depends largely on subjective, intuitive judgment (an art) or systematic analytic methods (a science). Understanding this question is important to the person when developing an effective approach to geospatial intelligence creation. To help understand these points of view, I will define the terms using the Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary, tenth edition, as:

- Art - the conscious use of skill and creative imagination in the production of anesthetic objects.

- Science - knowledge or a system of knowledge covering general truths or the operation of general laws, especially as obtained and tested through the scientific method.

Interestingly, there are those that consider integrative geospatial data tools, such as those found in GIS, as primarily aids to intuition and experience-based analysis and not the application of quantitative analytic methods. This seems contrary to the technical capabilities GIS brings to the geospatial intelligence. It is correct to say that there is no certain dividing line between art and science. Some contend there is no diving line at all and a pure scientific approach to geospatial analysis is impossible. The dissatisfaction with the push toward a science only perspective in GIS has been seen as a step backward by some. In this thinking, GIS’s models and analysis methods are not rich enough in geographical concepts and understanding to accurately reflect reality.

Geospatial intelligence is geospatial analysis, and geospatial analysis, at its core, is geography. Geography is both the conscious use of creative imagination in the representations of the earth and the science of developing general truths about the earth. For something to be automatable, it must be modeled and the facts (inputs) quantified. Since a model is a simplified abstract view of the complex reality, the model represents a limited set of rules which allows analysts to work out an answer if they have certain information. Quantifiability of the information is important because unquantifiable inputs cannot be tested, and thus unquantifiable results can neither be duplicated nor contradicted. However, we know that reliable models and data are not available for all analysis.

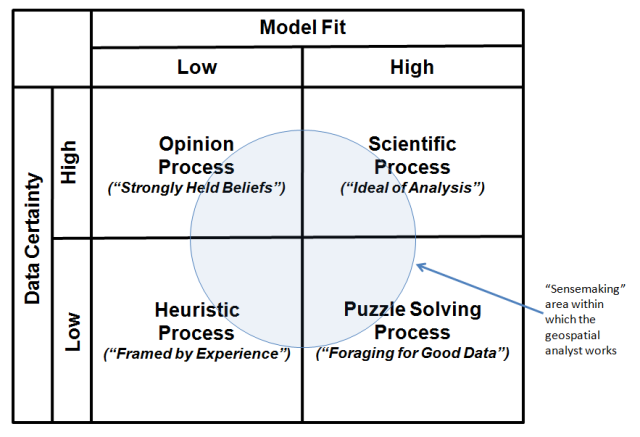

Pulling all of these thoughts together, the table in the image below categorizes the broad types of geospatial analysis. The upper right quadrantof the matrix identifies the ideal of GIS analysis as a Scientific Processin which there is good knowledge of the data and models surrounding an output. In the model, analysts understand the problem that confronts them and can take into account the key factors that bear on the problem. The notion of fixed-in-advance standard procedures typically plays an important role in such geospatial analysis.

However, many of the analytic tasks in geospatial intelligence fall outside of the scientific quadrant. Consider the Puzzle Solving Process (lower right) quadrant in which there is agreement on models, but disagreement on data. The notion of "foraging" for the data to solve the problem plays an important role in such analysis.

Analysis as an Opinion Process (upper left quadrant) is the opposite. In this analytic environment, there is agreement on data, but disagreement on model. Analysis is characterized by analysts involved in a struggle for influence, and decisions emerge from that struggle. This kind of analysis necessitates bargaining, accommodation, and consensus, as well as controversy. The bottom line is that conclusions are most often the result of bargaining between diverse and strongly held beliefs.

Intelligence analysis as a Heuristic Process (lower left quadrant) is the most contentious, with disagreement on data and models. Under these conditions, science and technology tools have significantly less direct relevance. Here, conclusions depend on parameters that change over the period the analysis is being made. As a consequence, the analytic process is experience-based. In the end, this is the framing of questions. They can only be framed, not solved, and thus the logic of argument and analysis is as important as the evidence.

Click to expand to provide more information

The "sensemaking" area within which the geospatial analyst works is the Puzzle Solving Process area.

| Model Fit - Low | Model Fit - High |

|---|---|

| Opinion Process ("strongly held beliefs") Data Certainty: high |

Scientific Process ("Ideal of Analysis") Data Certainty: high |

| Heuristic Process ("Framed by Experience") Data Certainty: low |

Puzzle Solving Process ("Foraging for Good Data") Data Certainty: high |

Is geospatial intelligence an art or science? Analytic problems can fall into any of the four quadrants ---- you, the analyst, need to understand the problem solving environment and the nature of the problem solving process. The term “sensemaking” is used as a term to describe the analysis process and incorporates traits associated with the classical definitions of both “art” and “science.” Sensemaking is more formally defined as the deliberate effort to understand events using explanatory structure that defines entities by describing their relationship to other entities. Data elicit and help to construct the frame; the frame defines, connects and filters the data.