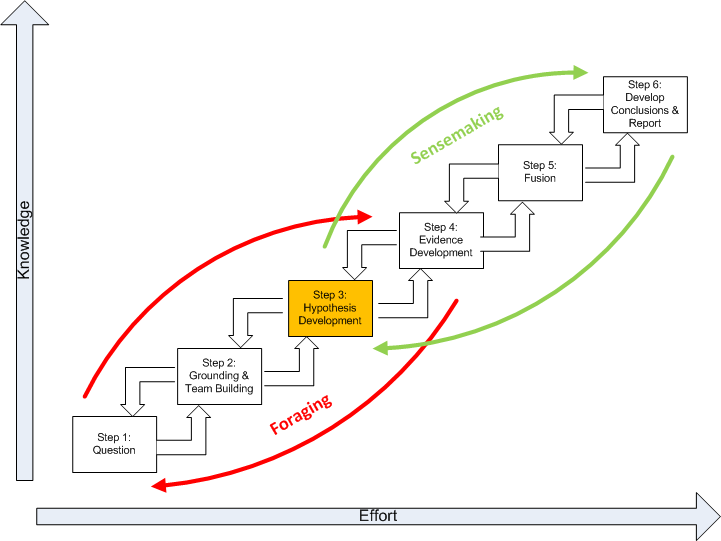

This chapter discusses the third step of the SGAM, highlighted below in gold, Hypothesis Development.

A hypothesis is often defined as an educated guess because it is informed by what you already know about a topic. This step in the process is to identify all hypotheses that merit detailed examination, keeping in mind that there is a distinction between the hypothesis generation and hypothesis evaluation.

If the analysis does not begin with the correct hypothesis, it is unlikely to get the correct answer. Psychological research into how people go about generating hypotheses shows that people are actually rather poor at thinking of all the possibilities. Therefore, at the hypothesis generation stage, it is wise to bring together a group of analysts with different backgrounds and perspectives for a brainstorming session. Brainstorming in a group stimulates the imagination and usually brings out possibilities that individual members of the group had not thought of. Experience shows that initial discussion in the group elicits every possibility, no matter how remote, before judging likelihood or feasibility. Only when all the possibilities are on the table, is the focus on judging them and selecting the hypotheses to be examined in greater detail in subsequent analysis.

When screening out the seemingly improbable hypotheses, it is necessary to distinguish hypotheses that appear to be disproved (i.e., improbable) from those that are simply unproven. For an unproven hypothesis, there is no evidence that it is correct. For a disproved hypothesis, there is positive evidence that it is wrong. Early rejection of unproven, but not disproved, hypotheses biases the analysis, because one does not then look for the evidence that might support them. Unproven hypotheses should be kept alive until they can be disproved. One example of a hypothesis that often falls into this unproven but not disproved category is the hypothesis that an opponent is trying to deceive us. You may reject the possibility of denial and deception because you see no evidence of it, but rejection is not justified under these circumstances. If deception is planned well and properly implemented, one should not expect to find evidence of it readily at hand. The possibility should not be rejected until it is disproved, or, at least, until after a systematic search for evidence has been made, and none has been found.

There is no "correct" number of hypotheses to be considered. The number depends upon the nature of the analytical problem and how advanced you are in the analysis of it. As a general rule, the greater your level of uncertainty, or the greater the impact of your conclusion, the more alternatives you may wish to consider. More than seven hypotheses may be unmanageable; if there are this many alternatives, it may be advisable to group several of them together for your initial cut at the analysis.

Developing Multiple Hypotheses

Developing good hypotheses requires divergent thinking to ensure that all hypotheses are considered. It also requires convergent thinking to ensure that redundant and irrational hypotheses are eliminated. A hypothesis is stated as an "if … then" statement. There are two important qualities about a hypothesis expressed as an "if … then" statement. These are:

- Is the hypothesis testable; in other words, could evidence be found to test the validity of the statement?

- Is the hypothesis falsifiable; in other words, could evidence reveal that such an idea is not true?

Hypothesis development is ultimately experience-based. In this experienced-based reasoning, new knowledge is compared to previous knowledge. New knowledge is added to this internal knowledge base. Before long, an analyst has developed an internal set of spatial rules. These rules are then used to develop possible hypotheses.

Looking Forward

Developing hypotheses and evidence is the beginning of the sensemaking and Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH) process. ACH is a general purpose intelligence analysis methodology developed by Richards Heuer while he was an analyst at the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). ACH draws on the scientific method, cognitive psychology, and decision analysis. ACH became widely available when the CIA published Heuer’s The Psychology of Intelligence Analysis. The ACH methodology can help the geospatial analyst overcome cognitive biases common to analysis in national security, law enforcement, and competitive intelligence. ACH forces analysts to disprove hypotheses rather than jump to conclusions and permit biases and mindsets to determine the outcome. ACH is a very logical step-by-step process that has been incorporated into our Structured Geospatial Analytical Method. A complete discussion of ACH is found in Chapter 8 of Heuer’s book.