4.2.1: The Nature of Feasibility Studies

A company will fund a prospecting and exploration if, and only if, they believe there is or will be a market for the commodity that they are seeking. As they begin to invest more time and money into the exploration of the deposit, they will concurrently be evaluating the three categories of factors described in the last lesson. If at some point, they believe that the project is not worth pursuing, they will most likely stop all work on the project and turn their attention to something else. If at the conclusion of the exploration program, and their “back-of-the-envelope” evaluation, they believe that the project has merit, then they will move to conduct a feasibility study. This is the subject of this lesson.

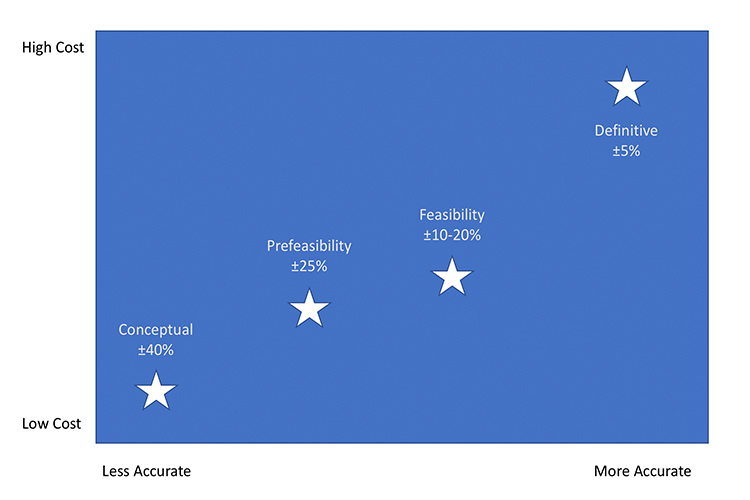

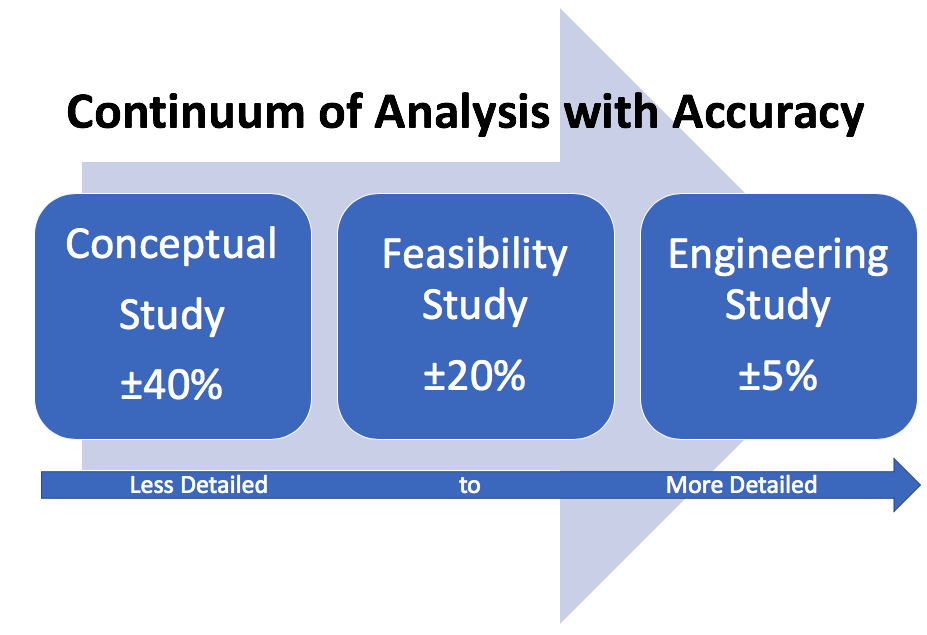

Practicing engineers and university professors use a variety of adjectives to describe the studies that are conducted and often do so without complete agreement. Common terms include conceptual (±40%), prefeasibility (±25%), feasibility (±10-20%), or definitive (±5% ) studies. The range of terms is meant to convey the cost to perform the study along with the accuracy, (shown parenthetically) of the study. Thus, a conceptual study may cost little to do, but only yield results that are ±40%, whereas the definitive or engineering study in which systems are designed and equipment is selected, will yield highly accurate results. Of course, the latter is laborious and expensive to conduct.

The back-of the-envelope considerations described in Lesson 4.1 would qualify as a conceptual or scoping study. I don’t want you to become overly concerned with the words, and accordingly, I suggest you remember it as follows.

The prefeasibility and feasibility studies have a similar goal, which is to estimate the financial merit of the project. Financial merit is quantified by metrics such as return on investment and the number of years until the operation becomes profitable, among other metrics. These studies will be used to make the go/no-go decision on the project. If the money to finance the project is to be raised publicly on the stock exchanges, then the prefeasibility or feasibility study must be made publicly available. The format for the published study is prescribed by law. So, what is the difference between the two studies? Some engineers or companies simply prefer to use one term instead of the other. Perhaps, the meaningful difference between the two terms is the amount of detail.

A certain amount of detail is prescribed by the legal standards for reporting publicly on projects in which investment is being solicited, and that constitutes the minimum level of detail. Often companies will want to invest more time and money into studying the feasibility of the project. The minimum level may be considered a prefeasibility study, and a more detailed examination of the feasibility may be considered a feasibility study.

With this understanding behind us, let’s get on with the subject of this lesson – feasibility studies.

The nature of feasibility studies has been prescribed by-laws for projects that will seek investments through public listings, e.g., stock exchanges. Most mining projects obtain at least partial funding through public investment, and as such the way we conduct and report on feasibility in a very similar fashion. Let’s take a look at the requirements, which have only come into being over the past few decades.

Since the earliest days of mineral prospecting and development, there has been no shortage of hucksters and shysters attempting to sell worthless mineral deposits. In the old days, the practice of “salting a claim”, i.e., deliberating adding gold or silver to the sample given to the assay office, separated many a person from their hard-earned money. Over the years, the methods to defraud investors became more sophisticated, the size of the investments became orders of magnitude higher, and when fraud occurred, it was likely to affect not just one or two hapless people, but large numbers. In the late 20th century (1990s), there were a couple of huge scams successfully perpetrated, and these caused great losses around the globe to institutional as well as individual investors. Further, it shook the public’s confidence in mining and made it very difficult for mining companies to raise capital.

The major mining countries, including the United States, Canada, and Australia, developed more rigorous standards for public disclosure of scientific and technical information that will be used to solicit investors. In a nutshell, the standards are attempting to ensure:

- the use of common definitions for words like measured resource;

- full disclosure of the people who developed the public report, including names, experience, and potential conflicts of interest; and

- disclosure of information that has a bearing on the worthiness of the project.

There are no significant differences among the standards used by the different countries, although you must ensure that your report meets the standard of the country in which you are going to list your investment opportunity. For example, if you are going to list on the New York Stock exchange, you must satisfy the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) rules, or to list on the Toronto Stock Exchange must comply with the Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA) rules.

We are going to use the Canadian standard because it provides a comprehensive approach that can be easily adapted to the U.S. (SEC), Australian (JORC), or other standards. Even if the intent is not to seek public investment, this standard provides a fine template for reporting on a feasibility study.