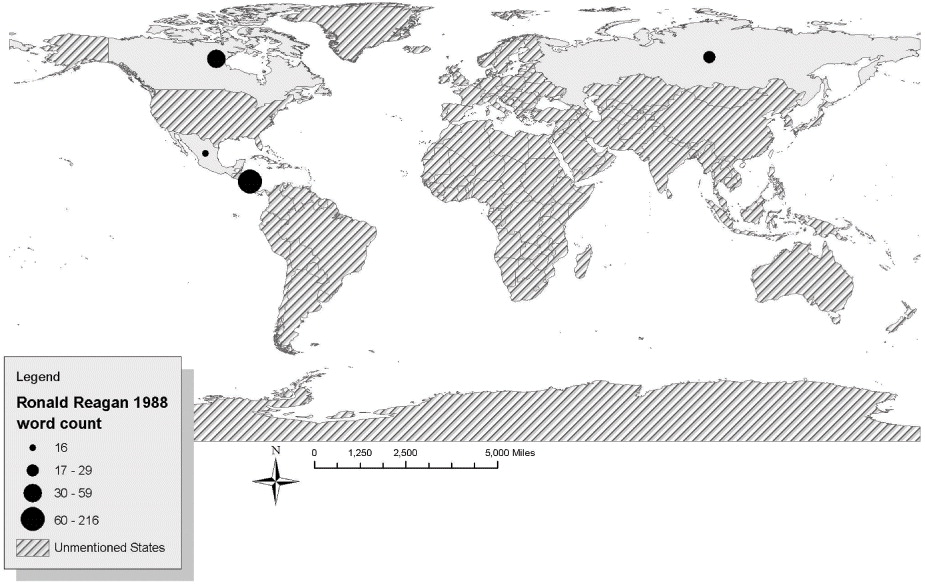

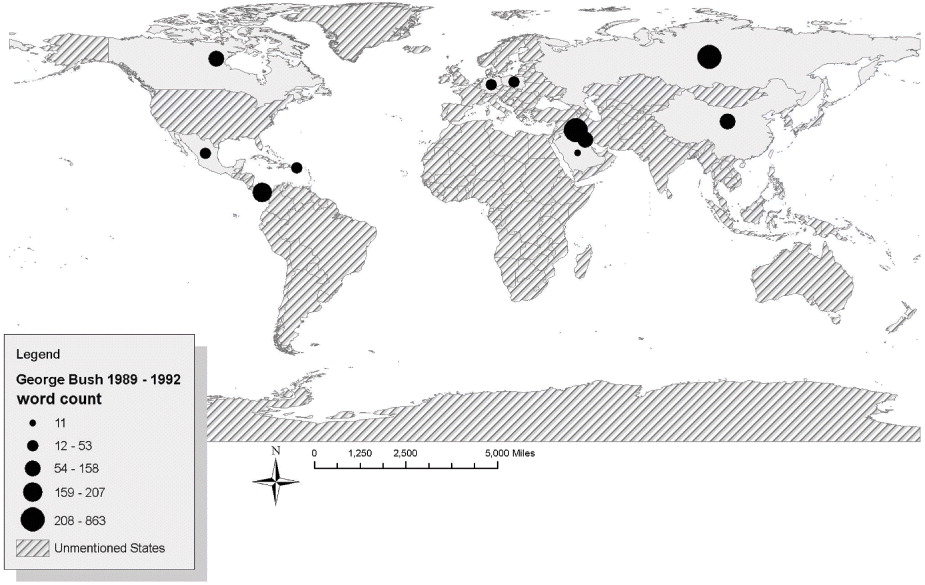

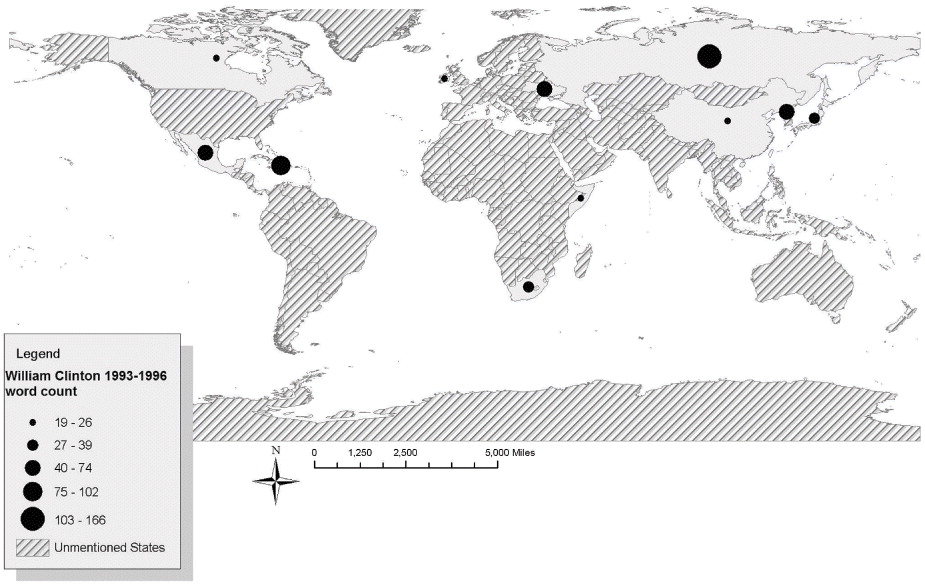

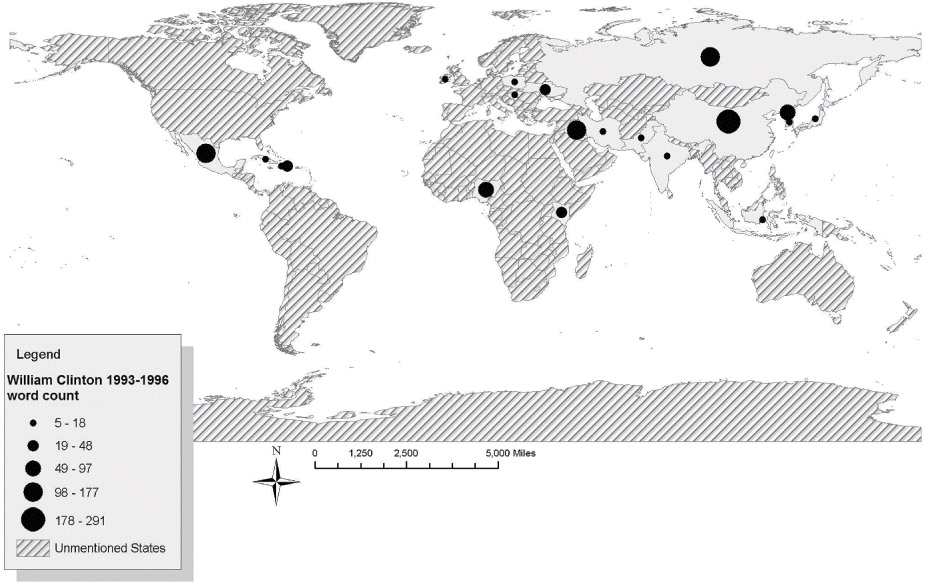

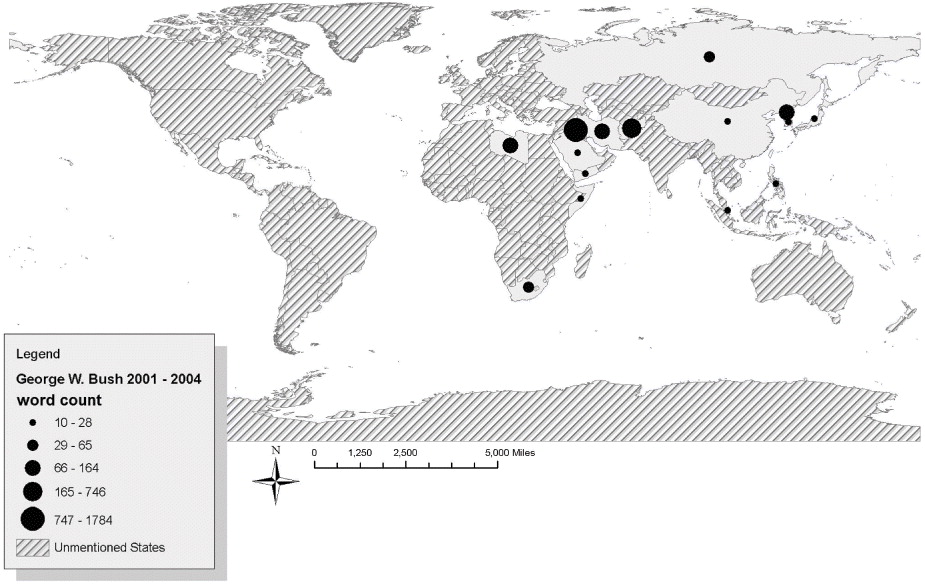

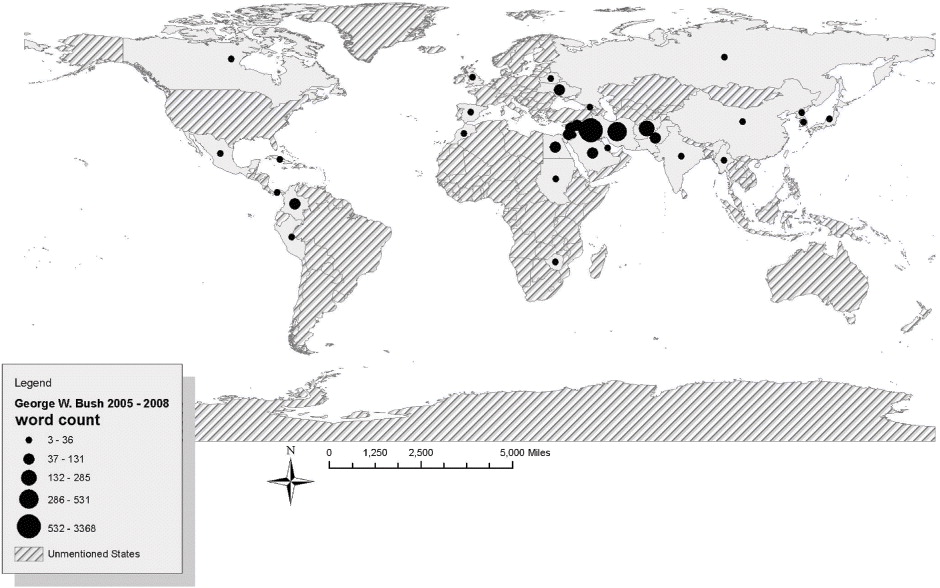

Geopolitical codes are not static. They change over time—as they should. A country’s geopolitical code is relational. It depends on relationships within a complex web of both domestic and international actors and conditions. This section in Flint (2012) explains the dynamism of geopolitical codes. Flint also discusses this dynamism in his 2009 article “Mapping the Dynamism of the United States’ Geopolitical Code: The Geography of the State of the Union Speeches, 1998-2008”. The following figures are from that article: Flint, C., Adduci, M., Chen, M., and Chi, S. (2009) Mapping the Dynamism of the United States’ Geopolitical Code: The Geography of the State of the Union Speeches, 1998-2008. Geopolitics, 14:4, 604-629.

In an effort to provide a visual representation of this dynamism, look at the following images from Flint, et al. (2009).

What do we understand by looking at and analyzing these maps (and their associated speeches)? According to Flint, et al. (2009), p. 625:

Three general trends can be discerned from the analysis of the speeches: an increase in reference to adversaries; an increase in the number of countries mentioned; and an increase in the geographic scope of the foreign policy references. There was a clear rise in the geographic scope of the speeches, especially the inclusion of all regions of Asia, and a concomitant increase in the number of countries mentioned. From the confined regional foci of Presidents Reagan and George H. W. Bush, the American public was introduced to a broad spectrum of countries, regions, and foreign policy issues through the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations.”

Over time, Flint, et al. (2009) highlights how our geopolitical code has expanded its foci to a more broad and diverse selection of countries, regions, and foreign policy issues. This is, of course, not coincidence, but certainly moves in concert with the trajectory of contemporary globalization that finds every country more economically, politically, and culturally enmeshed with each other.