Lesson 6: Cultural Landscapes

The links below provide an outline of the material for this lesson. Be sure to carefully read through the entire lesson before returning to Canvas to submit your assignments.

Note: You can print the entire lesson by clicking on the "Print" link above.

6.1 Overview

Introduction

Our discussion of nationalism took place primarily at broad scales (though it filtered down to the individual). In this lesson, we are going to zoom in a bit and examine a phenomenon that we experience on an everyday level: cultural landscapes.

Cultural landscapes are, we would argue, the primary physical manifestation of culture and human activity in space. They are both messy and symbolic, consisting of multiple layers that interlock, erode, reference and interrupt one another. But most of all, they are tangible and ubiquitous — and thus they can be an excellent primary source for understanding a place.

Objectives

Upon completion of this lesson, you will be able to:

- Evaluate cultural landscapes to determine local cultural and subcultural significance.

- Evaluate cultural landscapes to determine identity-based accessibility to spaces.

- Assess cultural landscapes to identify cultural and subcultural expectations for behavior based on identity and insider/outsider status.

- Critique the impact of new policies on cultural landscapes.

- Generate a spatio-cultural analysis of a landscape from anthropological data.

Questions?

If you have any questions now or at any point during this week, please feel free to post them to the GEOG 571 - General Discussion Forum. (That forum can be accessed at any time in Canvas by opening the Lesson 0: Welcome to GEOG 571 module in Canvas.)

6.2 Checklist

This lesson is one week in length. Please refer to the Calendar in Canvas for specific time frames and due dates. To finish this lesson, you must complete the activities listed below. You may find it useful to print this page out first so that you can follow along with the directions.

| Step | Activity | Access/Directions |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Read the Lesson 6 online lecture notes. |

The lecture notes can be accessed by clicking on the Lesson 6: Cultural Landscapes link in the Lessons menu on this page. |

| 2a |

Required Reading |

Duncan, J. and Duncan, N. (1988). (Re)reading the landscape. Environment & Planning D: Society and Space, 6(2), 117-126. Till, K. (2004). Political landscapes. In J. S. Duncan, N. C. Johnson, and R. H. Schein (Eds.), A companion to cultural geography (pp. 347-364). Blackwell. Note: Registered students can access the readings in Canvas by clicking on the Library Resources link. |

| 2b | Required Listen |

Davis, C. and Mars, R. (2018, August 14). It’s Chinatown [1]. 99% Invisible. Podcast audio. [listen to the first story; 23 minutes] |

| 3 | Optional Reading |

Chakraborty, D. (2016, April 18). When Times Square was sleazy [2]. The 80s. CNN. Norton, A. and Mars, R. (2013, January 23). In and out of LOVE [3]. 99% Invisible. Podcast audio. Schein, R. (1997). The place of landscape: A conceptual framework for interpreting an American scene. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 87(4), 660-680. Stilgoe, J. (1998). Outside lies magic. Walker and Company. Note: Penn State students should be able to access the optional readings though the Penn State Librareis. (Penn State Access ID login required.) |

| 4 | Complete the Lesson 6 Discussion Forum. | Post your answer to the Lesson 6 Discussion Forum in Canvas and comment on classmates' responses. You can find the prompt for the assignment in the Lesson 6 Discussion Forum in the Lesson 6: Cultural Landscapes module in Canvas. |

| 5 | Complete the Lesson 6 SoryMap exercise. | Submit you Lesson 6 StoryMap exercise to the Lesson 6 StoryMap Exercise dropbox in the Lesson 6: Cultural Landscapes module in Canvas. |

6.3 Cultural landscapes

When you think of the word ‘landscape,’ what is the first thing that comes to mind? For many of you, it might be something like this:

is licensed under CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication [7]

For others, it might be something like this:

(Public Domain [9])

Although these two images are separated by over three centuries and thousands of miles, and were created using vastly different technologies, they both fall into the category of landscape imagery. Both images represent some view of Earth’s surface as seen from some other point on the surface (as opposed to the birds-eye view we would get from a balloon, airplane, or satellite). Furthermore, as innocuous as they seem, both of these images reveal important and useful information about the cultural and economic practices of the places they represent. Or, in more technical language, these images communicate something about the cultural landscape.

We can think of landscape simply as a visible portion of Earth’s surface. We can further divide it conceptually between natural landscapes and cultural landscapes. Natural landscapes are simply landscapes as they exist without the intervention of human activity. By contrast, cultural landscapes are landscapes that have been shaped by human activity; you might also hear cultural landscapes referred to as the built environment.

While our instinctive ideas about landscape as an idyllic and picturesque scene that brings pleasure to the viewer is accurate within an art historical framework, within geography, cultural landscapes get at some of the messy interactions of everyday life. Cultural landscapes include more than scenes of rolling pasturelands, tranquil villages, and lush valleys protected by looming mountains and dominated by greenery. They also consist of things like street plans, monuments, architecture, and shops — and all manner of infrastructure such as sidewalks, streetlamps, traffic signs, and telephone poles.

Over the rest of this lesson we will quickly see that landscape is not just a nice view, but a nuanced aspect of our geography that can provide clues as to what is happening in a given place.

6.4 Sites of tension

While we often conceptualize landscapes through still or static images, landscapes themselves are inherently dynamic. They change over time — sometimes dramatically within a short period, as anyone who has witnessed economic and demographic shifts in the place where they live can attest. Topography is altered by hand or heavy equipment; trees, bushes, and flowers are removed or planted; buildings are raised or razed; old businesses close and new ones take their places, sometimes changing the facades of buildings. For example, the landscape of Times Square in New York City changed drastically during the 1990s, when a large-scale revitalization transformed from a seedy red-light district full of peep shows and porn shops into a thriving theatre district and tourist destination (for more on the history or to see photos before and after the transformation, see Chakraborty, 2016 or McMenamin, 2015).

Similarly, while landscapes may look settled, they embody a set of conceptual and material tensions. As Wylie argues at the outset, “landscapes are tension” (2007, p. 1). He lays out four sets of tensions that permeate landscapes: proximity vs distance (are we in the landscape or do we only observe it from a distance?), observation vs inhabitation (do we observe the landscape or do we live in it?), eye vs land (is it a way of perceiving the world as we find in art, or is it a tangible thing?), and culture vs nature (is landscape a human expression or are they produced by physical processes?).

Exercise:

Take a moment and revisit the two images in section 6.3. Consider the tensions identified by Wylie as you look at them. How do these tensions manifest in the images?

The answer to all of the questions prompted by Wylie, of course, is yes. We are both close to and distant from the landscape; we both observe and live in it. Likewise, it is both a tangible, material object and an artistic and aesthetic way of looking at that object — and that object is something that both humans and natural processes have active hands in shaping. Thus landscape exists in several contemporaneous states of tension that describe its formation, the ways we perceive and think about it, and our interactions with it.

Tensions made manifest

Here we want to flesh out Wylie’s points with three assertions. First, as landscape is both a tangible thing and a way of seeing, it is also a symbolic object. By symbolic here, we mean that landscape performs a kind of symbolic labor; that is, any given landscape symbolizes something. What it symbolizes is culturally constructed, both at the broad scale of the nation and at the narrower scale of various political and subcultural groups (see also Till, 2004).

For example, an image of family-run farms dotting a rolling, green countryside might variously symbolize the stewardship of the land, Christian values, the vast and only semi-visible network of food production, a simpler life, or a tradition that is disappearing with the rise of corporate farming. All of these interpretations are valid within the cultural context of the United States. They can be strategically deployed (e.g., projected among a series of other images during the National Anthem to provoke a sense of nationalism), but the results will vary with the audience. That is, landscape imagery does not have a uniform significance or symbolism, even within a given culture. A person’s socioeconomic status, political leanings, place identity, occupation, or knowledge of the processes that go into creating that particular landscape, inevitably impact how they receive a given landscape image. We will reiterate this point throughout the lesson.

Second, as landscapes are physical objects, they are produced by various forces and actors in the world. The natural landscape exists prior to human activity, and it is inherently unstable to begin with. Gradual forces such as weathering, erosion, and deposition create a slowly-changing canvas which more sudden events such as earthquakes, floods, and wildfires can alter radically in the course of weeks, days, or hours. Human activity has equally broad-scale consequences for the landscape: we habitually change the landscape through agriculture, infrastructure, settlement, and urbanization — as well as through resource extraction in places we don’t think of as habitats (e.g., mining and forestry). Even our attempts to preserve the natural landscape lend a human element, as with the shift away from fire suppression to controlled burns in national parks.

And just as landscapes are produced, they are also consumed by people. We have already noted that landscape performs a symbolic function. Consider, for example, the song “America the Beautiful,” which begins:

O beautiful for spacious skies,

For amber waves of grain,

For purple mountain majesties

Above the fruited plain!

In fact, the song is bookended by descriptions of the landscape — the last verse mentions the country’s gleaming “alabaster cities” and the chorus uses landscape imagery to situate the extent of the state “from sea to shining sea.” In this case, the beauty of both natural and cultural landscapes (and the fecundity of the former) is presented as a central feature of America’s appeal. The descriptions of these landscapes are meant to instill a sense of patriotism in the listener, while also claiming specific territory and demarcating the boundaries of the state.

Yet these symbolic uses of landscapes are not the only ways that people consume them. We habitually consume and analyze landscapes in order to gain information about the world around us. Whether we are looking through the window of an airplane, train, or car as we travel across long distances or we are scanning the streets and storefronts of an unfamiliar city or neighborhood, we are looking to the landscape to give us clues about the place in which it exists. In this regard, we can think of landscapes as texts that we read (see Duncan & Duncan, 1988). We will return to this more extensively in section 6.6.

Finally, landscapes are both controlled and contested. To address the first part of this statement, landscapes are things that landowners (be they public or private, collectives or individuals) control. To what degree they control them varies — from a vacant parcel overgrown with brush and vines or the crumbling facade of a brick rowhouse to a carefully manicured golf course or a stately mansion with a new roof and a perfectly weeded flower garden — and this may indicate how invested the landowner is in caring for the space.

It should also be noted that control does not necessarily equate to authenticity or innocence. Having control over the landscape, to some extent, means controlling the visual language of that landscape. For example, homeowner associations and historic districts can create policies that force homeowners to conform to certain architectural standards including paint colors, vegetation, and lawn maintenance standards.

Having control can also mean exaggerating certain of the landscape’s features, including its inhabitants. The pagodas of San Francisco’s Chinatown, for example, were carefully designed to heighten visibility of the presence of the Chinese community through highly exoticized and atypical uses of traditional architectural features (Davis & Mars, 2018). Similarly, the preservation of traditional architecture in Bhutan is part of the government’s Gross National Happiness development strategy. In this context, cultural preservation serves to reinforce the unique identity of the Bhutanese people; preserving the traditional characteristics of the built environment is thought to reinforce a national identity and to promote happiness through a strong sense of identity tied to, and reflected by, the landscape (Chimi, 2019).

Yet that control can give way to other actors as people contest a given landscape. That is, landscapes can be altered by people who lack the legal authority to change them. This can be destructive, as in the case of graffiti or vandalism.

![The image shows a US Postal Service Priority Mail sticker on which someone has drawn a cartoonish figure of a wolf wearing a skirt. To the right of the drawing are several lines of handwritten text which read, “Jon [sic] Faso is an asshole” and “Uncle Susan is a wolf.” The sticker has been affixed to the side of a parking meter.](/geog571/sites/www.e-education.psu.edu.geog571/files/images/L06/landscape-fig4x.jpg)

Yet illicit changes to the landscape are not necessarily destructive. Consider, for example, flowers sneakily planted on public land by guerrilla gardeners to beautify otherwise desolate urban landscapes. Or yarn bombing, in which people wrap objects in the landscape with knitted or crocheted coverings.

It is important to remember that landscapes also contain moving elements, including cars, people, and animals. These, too, can constitute or disrupt the landscape as they flow through (or refuse to flow through) the space. Parades and protests alike thus contribute to our experiences and understanding of landscape.

Read:

Duncan, J. and Duncan, N. (1988). (Re)reading the landscape. Environment & Planning D: Society and Space, 6(2), 117-126.

Till, K. (2004). Political landscapes. In J. S. Duncan, N. C. Johnson, and R. H. Schein (Eds.), A companion to cultural geography (pp. 347-364). Blackwell.

Recommended:

Chakraborty, D. (2016, April 18). When Times Square was sleazy [2]. The 80s. CNN.

Additional References:

Chimi. (2019). Architecture and Gross National Happiness in Bhutan. American Journal of Civil Engineering and Architecture, 7(3), 135-140.

McMenamin, M. (2015, July 24). “From dazzling to dirty and back again: A brief history of Times Square [11].” MCNY Blog: New York Stories (blog), Museum of the City of New York.

Wylie, J. (2007). Landscape. Routledge.

6.5 Reading cultural landscapes

In the previous section, we argued that landscapes are not only produced, but also consumed. More specifically, following Duncan and Duncan (1988), we took the position that landscapes can be thought of as texts that we can read. In this section, we turn to this idea in more detail.

Foundations

Before we can talk about how to read landscapes, it’s helpful to understand what purpose this exercise serves, and what its limits are. A cultural landscape in its current form is always the product of a long series of overlapping choices made by people (collectively or individually), and mediated by the culture in which it exists. Careful reading can thus produce a wealth of information that extends from the present backwards in history.

It is also important to understand the difference between actively and passively reading the landscape. For many of us, the landscapes we see every day are so familiar that we have internalized their elements and hardly think about them. When navigating somewhere, we might actively seek a particular feature on the landscape (e.g., a specific building number, street sign, or landmark), but when we do so, we tend to disregard the rest. Some features, such as markings for lanes or parking spaces, or street signs, we use in a referential way, but their visual aspects are generally unremarkable unless something about them has changed (or unless we go to a place where the markings are stylistically different. This kind of engagement with the landscape is passive, and it is likely only to reveal the most obvious information.

Actively reading the landscape is a process that requires both an attention to detail and the ability to understand the specific collection of features as a whole. For example, focusing on a single element of a landscape, as in figure 6.7a below, tells us only that there is a Shake Shack somewhere in the world.

Yet, as figure 6.7b shows us, when we consider that single element with regard to other elements in the landscape, we are better able to situate it. In this case, the presence of signage in Turkish and the Turkcell banner in the upper right hand corner indicate that this is part of the Turkish landscape. Yet the elements in isolation tell us little; when we (actively) synthesize those elements, we might notice first, that there is a US-based fast food restaurant in this neighborhood, and second, that it belongs to one of the smaller American fast food chains. This might suggest to us first that this is a tourism-dependent area, and second, that there are American tourist dollars flowing into this landscape. (This was a Shake Shack that Dr. Livecchi encountered on İstiklal Caddesi during a visit to Istanbul in 2016. To the best of his knowledge, that Shake Shack is gone, but others have sprung up in the city.)

The rest of this lesson will address what the landscape can tell us, and presumes an active reading of the landscape. Note that while identifying the visual elements is an integral part of reading the landscape, an in-depth landscape analysis typically involves observation of individuals within the space, and often entails additional research to fully appreciate the history and social significance of the space.

NOTE:

Many of the examples that follow come from Kingston, New York, where Dr. Livecchi currently lives. We’re using these as examples in part due to ease of data collection (it’s easier to provide photos that display the relevant information), and in part because it affords a fair amount of diversity in its landscapes, and thus can provide a variety of examples.

Whose culture?

First and foremost, the cultural landscape gives us some indication of the dominant culture, as well as the economic circumstances of the place. For example, compare the images below.

is licensed under (CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication [7])

The architectural styles, signage, width of the streets, and infrastructure in these landscapes give us hints as to where they are. Although these landscapes may share some similarities, the visible qualities of each set them apart from one another. Even if we cannot readily identify the locations of these landscapes, we can be certain that they were produced within different cultural contexts. These images were chosen because they provide relatively clear indicators of location; it is important to remember that in some cases the differences may be small enough that they require close attention to detail — street lane markings, curb cuts, sidewalk and crosswalk design, and the (in)visibility of things like telephone or electrical lines are all indicators that observers often overlook because they are either meant to be overlooked or they are so familiar that we only passively recognize them.

All of these landscapes are situated in tourist areas of different cities. The differences in architecture, street design, and visible infrastructure (e.g., street lights, signage, bike racks, etc.) offer some idea as to where they were taken; they also suggest the histories of the places. The types of structures and decorative flourishes tell us that these are spaces where people either congregate or intend to spend money — and the condition of the structures indicates that someone (or several someones) has invested money into upkeep, presumably to maintain an inviting space that welcomes tourists.

Form follows function, sometimes

Second, the landscape can tell us something about the intended function of the space, and for whom the space is intended. For example, consider the landscapes in figures 6.12 and 6.13.

The landscape in figure 6.13 will be familiar to anyone who has visited a rural cemetery in the United States. Even without knowing the location, the language used on the stones, or the visual culture associated with the landscape in figure 6.12, even a casual observer would recognize it as a cemetery (despite the obvious differences with regard to density and groundcover). In both of these images, the kinds of features and their arrangement give us information as to these landscapes’ functions.

In some cases, function also entails some assumptions about for whom the landscape was designed. Figures 6.14 and 6.15 below provide two contrasting examples.

is licensed under (Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International [15]).

is licensed under Attribution 2.0 Generic [19]

These two landscapes physically express their intended functions and audiences. The playground is sized for children, and surrounded by apartment buildings. The red-light district relies on an established visual signal (red lights) to denote the availability of sex workers. Although the playground landscape is deserted, we would expect to see children playing. Adults without children might seem out of place and suspect. Likewise, the notable absence of children in the red-light district is in line with our expectations; their presence might be puzzling or concerning, as they might seem out of place.

As a corollary to this, elements on the landscape sometimes broadcast not only who is expected within them, but who is welcome within them. Consider, for example, the Old Dutch Church in Kingston, New York.

Even casual observers familiar with the United States will instantly recognize the building as a Christian church (and as an old church, given the presence of the churchyard and the stone and style of the headstones); we can surmise without real question that the space has a religious function and that members of some Christian denomination are welcome there. What stands out, however, is the flagpole, from which four flags fly: the American flag, a Black Lives Matter flag, a Pride flag, and a Transgender Pride flag. These symbols on the landscape are a visible means by which the church proclaims its identity as both American and as welcoming to members of social groups who have historically been marginalized.

Resistance

Third, landscapes can tell us a little about resistance to the local social order or to local conventions. Some activity leaves traces that indicate a use other than what was intended. For example, municipal officials may install benches in public spaces with the intent that people will sit on them — yet those same benches might also be used by homeless populations as somewhere to sleep. Likewise, skateboarders find particular joy in sliding across benches and low walls of concrete or granite. The presence of hostile or defensive architectural features such as spikes (figure 6.17), or less obvious features such as extra rails on benches (figure 6.18) visibly indicate the contested nature of some landscapes.

is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 [22]

is licensed under Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International [15].

What matters most?

Fourth, the landscape can tell us what is important to a particular community — both in terms of what a community claims is important in an official capacity, and in terms of resistance to that official line by smaller subgroups within that community. With regard to the former, things like monuments and street signs are visible, physical markers that reflect the values officially embraced by the community (discursively constructed or mediated by people in power). Choosing to commemorate individuals by naming or renaming streets after them is an established practice. Consider, for example, streets in cities with which you are familiar that were named for former political leaders such as presidents, governors, or mayors — or streets that are given secondary names to honor individuals, especially those fallen in combat. Later renaming of streets and alterations or removals of monuments can reflect cultural changes, as with the removal of Confederate monuments or the names of Confederate generals from military bases. Till (2004) captures this dovetailing of culture, politics, and space in the ways that landscapes are manipulated to political ends on both national and local scales.

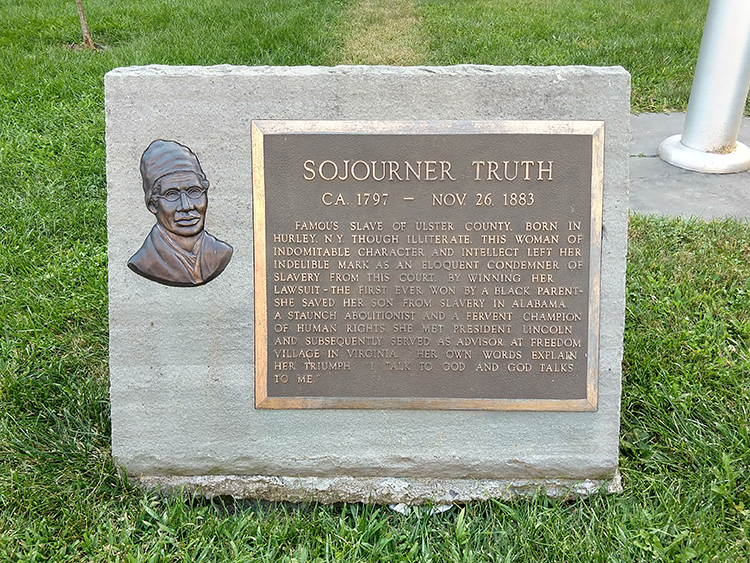

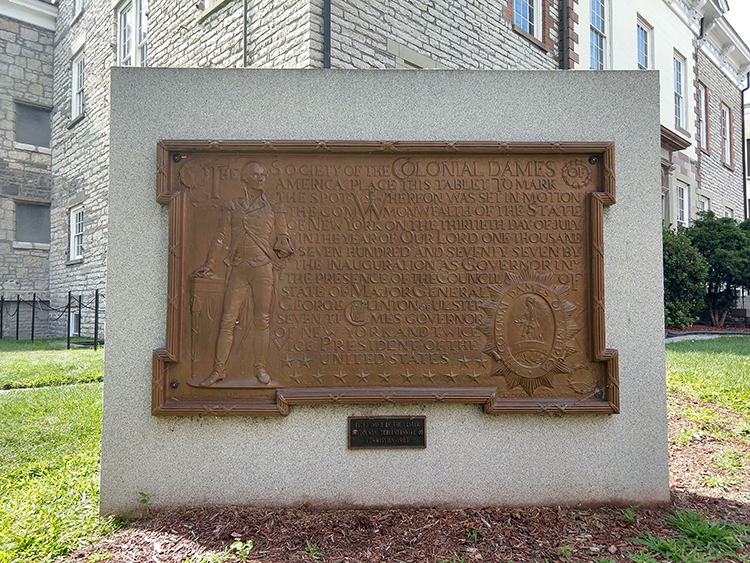

It is perhaps easy to overlook street signs; we are accustomed to using them as references for navigation and to ignoring them at other times. Monuments, by contrast, are designed to stand out on the landscape. Their placement, size, and construction provide some indication of their importance to a given community. The Ulster County Courthouse in Kingston, New York (fig 6.19) provides an interesting example here.

On the courthouse grounds stand two monuments. One of these (figure 6.20) is just visible just beyond the fence, near the base of the flagpole. The other (figure 6.21) stands just beyond the left edge of figure 6.19.

The text of this monument reads:

“SOJOURNER TRUTH

CA 1797 - NOV 26, 1883

FAMOUS SLAVE OF ULSTER COUNTY, BORN IN HURLEY, N.Y. THOUGH ILLITERATE, THIS WOMAN OF INDOMITABLE CHARACTER AND INTELLECT LEFT HER INDELIBLE MARK AS AN ELOQUENT CONDEMNER OF SLAVERY. FROM THIS COURT, BY WINNING HER LAWSUIT - THE FIRST EVER WON BY A BLACK PARENT - SHE SAVED HER SON FROM SLAVERY IN ALABAMA. A STAUNCH ABOLITIONIST AND A FERVENT CHAMPION OF HUMAN RIGHTS, SHE MET PRESIDENT LINCOLN AND SUBSEQUENTLY SERVED AS ADVISOR AT FREEDOM VILLAGE IN VIRGINIA. HER OWN WORDS EXPLAIN HER TRIUMPH: “I TALK TO GOD AND GOD TALKS TO ME.”

The text of this monument reads:

“THE SOCIETY OF THE COLONIAL DAMES OF AMERICA PLACE THIS TABLET TO MARK THE SPOT WHEREUPON WAS SET IN MOTION THE COMMONWEALTH OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK ON THE THIRTIETH DAY OF JULY IN THE YEAR OF OUR LORD ONE THOUSAND SEVEN HUNDRED AND SEVENTY SEVEN BY THE INAUGURATION AS GOVERNOR IN THE PRESENCE OF THE COUNCIL OF STATE OF MAJOR GENERAL GEORGE CLINTON OF ULSTER SEVEN TIMES GOVERNOR OF NEW YORK AND TWICE VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES.”

Both monuments stand on the grounds of this historic courthouse — one to commemorate the founding of the State of New York (relying on the image of President Washington to establish its connection to the nascent United States), and one to commemorate the legal success of a Black woman abolitionist from the region. Both commemorate events that took place here, and both events are significant to the region’s history — though for vastly different reasons. These elements on the landscape symbolically represent some value or idea that officials were trying to communicate publicly at the time the monuments were erected.

Landscapes with monuments such as these are often the sites of celebrations — and protests. Event organizers and speakers frequently make reference to the symbols visible in the landscape around them in order to appeal to the emotions of the onlookers, whether to instill a sense of pride or to inspire them to protest.

One final example will help illustrate this point. There is a park in Kingston, New York, called Academy Green. The park is a large triangle of grass bounded by Clinton Avenue, Albany Avenue, and Maiden Lane. This space is situated in a liminal part of Kingston, outside the historic Stockade District and on the edge of a residential neighborhood, with a major thoroughfare (Albany Avenue) defining its longest side.

On the green are three 11-foot-tall bronze statues on plinths, all of historic figures: Peter Stuyvesant (the director general of the New Netherland colony before it was given to the British in the mid-17th century), George Clinton (first governor of New York State, and still not the funk musician), and Henry Hudson (English explorer who navigated up what is now the Hudson River). Cast in 1898, the statues were initially part of a set adorning a bank building in New York City, and were rescued from a junkyard by an individual in 1943, who donated them to Ulster County (Schwarz, 2018).

The park generally functions during the day as a space of socialization for adults within Kingston’s Black community. Given its visibility along Albany Avenue and its position relative to other neighborhoods, it also serves as one of several active sites of protest within Kingston. In 2020 and 2021, the park has seen nonviolent protests against police brutality (particularly in the wake of George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis), hosted weekly walks for Black lives, and has served as the rallying point for a protest and march against the sale of Chiz’s Heart Street — a large group home for mentally ill people — to a wealthy hotel developer (a common theme; Kingston is experiencing a wave of pandemic-enhanced gentrification as affluent New Yorkers leave Manhattan and Brooklyn for the Mid-Hudson Valley).

In 2020, Kingston-based community organizer Frances Cathryn began a project to point out the historically racist actions of the figures commemorated by the statues in the park. In an op-ed piece, she notes that there is an inherent irony as “local activists of color and young Black students gather at Academy Green and call for the acknowledgment of their basic civil rights in front of an enslaver” (Cathryn, 2020). Yet perhaps it’s not an innocent irony: event organizers or participants who are aware of the landscape might use those features as references to stir up stronger emotions among participants.

Landscape is not something that simply exists in the background. An understanding of the landscape can enable individuals and groups to deploy symbolically across a wide range of readings, and to make a variety of different public statements.

Read/Listen:

Davis, C. and Mars, R. (2018, August 14). It’s Chinatown [1]. 99% Invisible. Podcast audio. [listen to the first story; 23 minutes]

Recommended:

Norton, A. and Mars, R. (2013, January 23). In and out of LOVE [3]. 99% Invisible. Podcast audio.

Schein, R. (1997). The place of landscape: A conceptual framework for interpreting an American scene. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 87(4), 660-680.

Stilgoe, J. (1998). Outside lies magic. Walker and Company.

Additional References:

Cathryn, F. (2020). The Kingston Monument Project: A community organizer on replacing the monuments in our public spaces [25]. Chronogram.

Duncan, J. and Duncan, N. (1988). (Re)reading the landscape. Environment & Planning D: Society and Space, 6(2), 117-126.

Schwarz, A. (2018, September 12). An appreciation of Academy Green’s statues [26]. Hudson Valley One.

Till, K. (2004). Political landscapes. In J. S. Duncan, N. C. Johnson, and R. H. Schein (Eds.), A companion to cultural geography (pp. 347-364). Blackwell.

6.6 Caveats and limitations

Reading the landscape can be an informative exercise, but it comes with some caveats. First, it is important to bear in mind that while specific features of any given cultural landscape may be the result of a single individual’s decisions, landscapes in general are the accumulation of long histories of building, policy, zoning, and active use by humans.

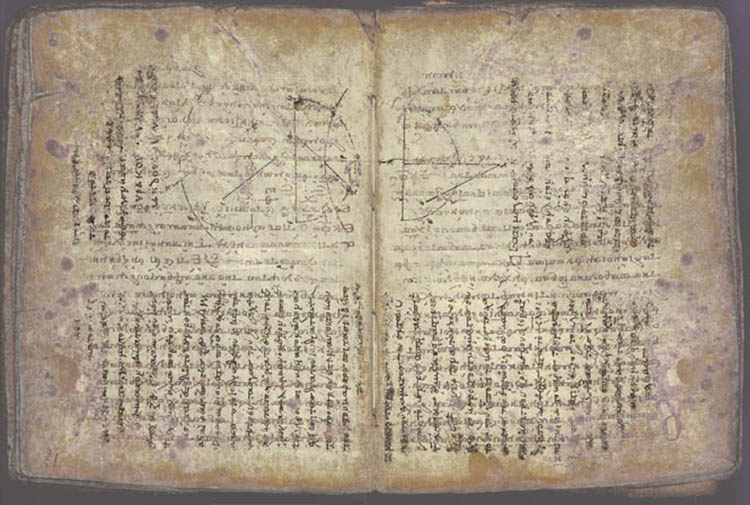

We can think of landscapes, therefore, as similar to palimpsests — ancient manuscripts on which the original writing has been scraped away and the base material has been reused; traces of the original writing remain.

We often overlook traces of older landscape features — electrical boxes that once controlled stop lights that are no longer there, altered brickwork or stonework where windows or doors have been added or removed, random paving stones leading to empty lots, or inscriptions that reflect a building’s original use (as in figure 6.24 below). Yet these are clues to the site’s history.

Second, it is imperative to understand any given landscape within the broader context of the place. Each landscape is part of a broader system, and it is useful to understand how that landscape reflects or differs from other parts of the place in which it is situated. For example, Academy Green’s situation in the liminal space between neighborhoods makes it one that is less frequently policed than other parts of the city, and its proximity to major streets that connect City Hall and the Ulster County administrative offices make it a strategic rallying point.

Consequently, while we may look to particular features as clues to some aspect of the landscape, we always have to consider that landscape within its broader cultural, geographical, and historical context (see Schein, 1997). An in-depth analysis of the landscape accepts the visual reading as both an initial assessment and a starting point for further research.

Third, not everything that is important to a location is visible within the landscape — in fact, whether by policy or by design, some landscapes have been painstakingly altered to conceal or minimize the visibility of certain features, such as sprinkler systems, phone lines, electrical lines, or their own construction. What’s visible is important, but it doesn’t always provide the whole story.

Fourth, all readings of the landscape are subjective, and individuals may emphasize different aspects of the landscape — in part, because their experiences and identities may have made them more attuned to noticing, identifying, or understanding certain features. Using the World Trade Center as an example, Morin demonstrates how a single landscape can be interpreted in a number of differing ways:

The attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City in September 2001 highlighted the vastly different meanings that that corporate landscape represented for observers at numerous scales and locations, both before and after the attacks: as emblem of technological ingenuity, modernity, progress, the success of global capitalism and democratic government, and certainly a new wave of American patriotism; to more decentred understandings — US political and economic vulnerability, anti-capitalism, a holy war waged against the USA, just desserts or a wake-up call for unjust American foreign policy and hegemony, and mourning and loss of loved ones and livelihoods in the New York area. The fact that these meanings and interpretations all co-existed simultaneously forced a recognition that not only could the same landscape carry vastly different meanings to different observers, but that the landscape itself was also a reference to a much larger set of social relationships, domestic and global, that required attention and contextualization. (2009, pp. 289-290)

Subjectivity in reading the landscape happens not only among individuals, but also within groups. Duncan and Duncan (1988) note the existence of “textual communities” — groups of people who share a reading or understanding of a given text; we might argue that identity groups, to some extent, can act as textual communities (bearing in mind, however, the multilayered nature of identity).

References:

Duncan, J. and Duncan, N. (1988). (Re)reading the landscape. Environment & Planning D: Society and Space, 6(2), 117-126.

Morin, K. M. (2009). Landscape: Representing and interpreting the world. In N. J. Clifford, S. L. Holloway, S. P. Rice, and G. Valentine (Eds.), Key concepts in geography (pp. 286-299). Sage.

6.7 Cultural Landscapes and Human Security

In the previous sections we introduced the idea of cultural landscapes and discussed their significance and to read them. Our approach so far has been to talk about cultural landscapes as a combination of setting, reflection, and co-constructor of our everyday actions and interactions. Most of the images in the previous sections depicted relatively clean and orderly spaces that many of you may find pleasant.

Yet, as we hinted at in section 6.4, many of the landscapes we interact with (in some cases, on a regular basis) show signs of what sociologists and criminologists refer to as disorder: untended lawns or medians, graffiti, cracked or broken sidewalks or curbs, houses with missing or boarded-up windows, litter strewn across the ground, streets riddled with potholes, buildings with peeling or flaking paint, vandalism, rotting woodwork and rusty ironwork—and the list goes on. In addition, you might sometimes observe activity in the landscape that suggests disorder: loitering, panhandling, public drinking or drug use, or groups of unsupervised youth wandering about.

These signs of physical and social disorder on the landscape may lead people to perceive the landscape as unsafe. As Chappell and company argue, “some research indicates that neighborhood disorder…is a better predictor of fear than serious crime” (2011, p. 522). We can reinterpret this statement from a geographical perspective thus: people read landscapes as part of their daily habits (often without realizing it); landscapes with visible signs of disinvestment are disorderly; and disorderly landscapes are often perceived as dangerous, regardless of whether or not they are actual sites of crime.

The presence of physical and social disorder in the landscape have led to at least two important (and related) theoretical interventions in criminal justice: crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) and broken windows.

Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design

CPTED emerged in the early 1970s when criminologist C. Ray Jeffrey and architect and urban planner Oscar Newman independently published books that pointed to the environment as a contributing factor of crime. Their work rested in part on a foundation created by urbanist Jane Jacobs. In her book 1961 Death and Life of Great American Cities (which is still widely read today), argued that in order for cities to feel vibrant, it is necessary to have a clear delineation between public and private space, to have “eyes on the street”—everyday people whose presence constitutes community but also surveillance, and an environment that is built to facilitate that surveillance.

Building on these ideas, Newman proposed the idea of defensible space—a space that is designed to enable individuals to contribute to their own safety through four design elements:

- Territoriality (using both real and symbolic barriers that indicate ownership of space)

- Surveillance (enabling people to observe and surveil one another through windows, entrances, etc.)

- Image (influencing the perception of space through design)

- Geographical juxtaposition (the ability of adjacent space to influence the security of one another

Together, these elements theoretically create a sense of ownership, community, and responsibility for spaces (Cozens & Love, 2015). The argument goes that in well-designed (or defensible) spaces, people who are there for legitimate reasons feel safe, while people who are inclined to commit crimes feel uncomfortable doing so.

CPTED has been championed by architects and urban planners, and has been refined over the years to promote a holistic approach to designing the built environment in ways that promote community inclusion. Contemporary CPTED models incorporate additional elements and contextualize them in broader social systems. Principles of CPTED have diffused from the US throughout North America, and have been embraced by government agencies in Europe, Australia, Asia, and South Africa, among other places (Cozens & Love, 2015).

Given the increasing complexity of CPTED, it is difficult to fully assess its effectiveness in crime prevention (Cozens & Love, 2015), yet the results are promising. A meta-analysis of CPTED (Ceccato, 2020) has found considerable support for the efficacy of its design elements. In particular, attention to lighting, the use of surveillance cameras, and maintenance of spaces seem to promote increased use of public spaces, reduced fear of crime, and reduced incidents of crime. This is evident in MacDonald and Branas’s (2019) Philadelphia LandCare case study [29], a project in Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood that converted vacant lots into pocket parks. The investigators found significant reductions across gun assaults, shootings, and nuisance crimes, with particularly strong results in neighborhoods below the poverty line.

Broken Windows

In 1982, political scientist James Q. Wilson and criminologist George Kelling presented this idea as the basis for their theory of broken windows in an article in The Atlantic. Their idea, in brief, was that untended social and physical disorder on the landscape would cause the informal social controls that keep communities safe (i.e., through social cohesion) to diminish. As people begin to see a landscape as disorderly, they are less likely to engage with others in the landscape, leading to a spiral of fear and social disinvestment:

At this point it is not inevitable that serious crime will flourish or violent attacks on strangers will occur. But many residents will think that crime, especially violent crime, is on the rise, and they will modify their behavior accordingly. They will use the streets less often, and when on the streets will stay apart from their fellows, moving with averted eyes, silent lips, and hurried steps. (Wilson & Kelling, 1982, p. 31)

From there, they argue, the landscape becomes open to crime—that, in effect, perception becomes reality.

All of this may sound academic, but it had real-world implications. Wilson and Kelling’s article was the catalyst for a new direction in policing: disorder policing. In its harshest form, disorder policing manifests as the kind of ‘zero-tolerance’ that was first instituted in New York City in the 1990s during the Guiliani administration and has since been exported to cities in Iraq, Brazil, Norway, Australia, and Colombia among others (for more on the history of its implementation, see Mitchell, 2010). This style of policing targeted ‘quality of life’ infractions such as loitering, littering, vandalism, and other low-stakes behaviors.

Disorder policing, and zero-tolerance policing in particular, is controversial, and its effectiveness is mixed at best. A decrease in crime through the 1990s and into the 2000s led some policymakers to hail zero-tolerance policing in New York City as a success, though several scholars have pointed out a number of other factors, such as a reduction in the use of crack cocaine, economic growth, and changes in age structure may also account for the decline in crime rates (Braga et al., 2015; Diniz & Stafford, 2021). Others point out that it is difficult to tell which successes are the result of disorder policing as opposed to community-based approaches, as many policing strategies informed by broken windows theory also tend to include problem-solving, place-oriented, or deterrence components (Weisburd et al., 2015).

Part of the problem with measuring the effectiveness of disorder policing is that it’s not clear which kinds of disorder are good indicators of the development of crime. For example, Diniz and Stafford (2021) found that graffiti (a common measure of physical disorder) had no clear spatial relationship to a variety of crimes (personal crimes, property crimes, sex crimes, gun violence, or drug trafficking) in downtown Belo Horizonte, Brazil, despite an aggressive zero-tolerance policing campaign in the city.

Some scholars note that there have been too few studies on disorder policing to support the claims of success (see, e.g., Weisburd et al., 2015), and existing studies provide a mixed bag of results. In a meta-analysis of 30 tests of disorder policing, Braga and colleagues found that “disorder policing strategies generate noteworthy crime control gains” (2015, p. 580) across various measures of crime—but that the type of strategy matters. They found overall that aggressive zero-tolerance approaches that respond to specific behaviors were not effective, while place-based and community problem-solving approaches did significantly reduce crime.

Yet Wilson and Kelling’s (1982) theory is not a theory of crime reduction. It is a theory that uses elements of cultural landscapes to prevent a place from becoming a site of crime by preventing the fear that leads to the erosion of informal social controls, rather than a theory of how to respond to existing crime hotspots. Taking a closer look at the studies reviewed by Braga and colleagues (2015), Weisburd and company (2015) found that all but one focused on crime reduction rather than fear reduction—and the one that did focus on fear reduction found that disorder policing did not significantly reduce fear. They further note that the model suggested by Wilson and Kelling may take years to develop, and it is unclear just how much time it would take for disorder in the landscape to translate to the kinds of effects they predict.

Regardless, people’s perceptions of the landscape do impact their perceptions of safety and security. Chappell and colleagues (2011) found that when accounting for both social and physical disorder, social disorder has no significant impact on quality of life—but physical disorder does, even though it is not necessarily an indicator of crime. These perceptions can impact our daily activities, including the routes we choose to take and the destinations we visit, as well as the routes and places we avoid due to fear.

Landscapes and Security, Revisited

With all of this in mind, it is important to take stock of interactions of landscape and security:

- We read danger into the landscape through disorder.

- We often perceive disorderly landscapes as dangerous even if they aren’t.

- Policymakers often might turn to landscape-oriented interventions such as CPTED and models based on Broken Windows theory to address fear and crime in public spaces.

- Though they are both landscape-oriented models, interventions based on these two approaches are implemented very differently and have varying results.

In short, the ways that we perceive cultural landscapes has an impact on quality of life, and policymakers are aware of this. Interventions that target human security based on landscape factors merit careful consideration.

Further Exploration:

Vedantam, S. (Host). (2016, November 16). Broken windows [30] (No. 50) [Audio podcast episode]. In Hidden Brain. Hidden Brain Media.

References:

Braga, A. A., Welsh, B. C., and Schnell, C. (2015). Can policing disorder reduce crime? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 54(4), 567-588.

Ceccato, V. (2020). The architecture of crime and fear of crime: Research evidence on lighting, CCTV and CPTED features. In V. Ceccato and M. K. Nalla (Eds.), Crime and fear in public places: Towards safe, inclusive and sustainable cities (pp. 38-71). Routledge.

Chappell, A. T., Monk-Turner, E., and Payne, B. K. (2011). Broken windows or window breakers: The influence of physical and social disorder on quality of life. Justice Quarterly, 28(3), 522-540.

Cozens, P., and Love, T. (2015). A review and current status of crime prevention through environmental design [31] (CPTED). Journal of Planning Literature, 30(4), 393-412.

Diniz, A. M. A., and Stafford, M. C. (2021). Graffiti and crime in Belo Horizonte, Brazil: The broken promises of broken windows theory [32]. Applied Geography, 131, Article 102459.

MacDonald, J. M., and Branas, C. C. (2019, September 25). Cleaning up vacant lots can curb urban crime [29]. Manhattan Institute.

Mitchell, K. (2010). Ungoverned space: Global security and the geopolitics of broken windows. Political Geography, 29, 289-297.

Weisburd, D., Hinkle, J. C., Braga, A. A., and Wooditch, A. (2015). Understanding the mechanisms underlying broken windows policing: The need for evaluation evidence. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 52(4), 589-608.

Wilson, J. Q., and Kelling, G. L., (1982, March). Broken windows: The police and neighborhood safety. The Atlantic Monthly, 249(3), 29-38.

6.8 Introduction to Google MyMaps

Introduction

So far this course has focused predominantly on Esri’s ArcGIS Online platform to conduct exercises relevant to the coursework. As part of your StoryMap exercise in generating a spatio-cultural analysis of a cultural landscape, you may want to include a map of those landscapes. In addition to using ArcGIS Online’s Map Viewers, it may be easier to create a Google MyMap to embed into your story map. This brief tutorial will introduce you to the basic functionality of Google MyMaps.

Google MyMap Basics

- You’ll need a Google account. You can either use your existing Google account, or you can create an account for this course.

- Go to the Google MyMaps page [33].

- From the Google MyMaps main page, select “Get Started”:

- To create a new map, click the “Create New Map” button at the top left:

- This will open a blank map called “Untitled Map.” Left click on the words “Untitled Map” to change the name and provide a description.

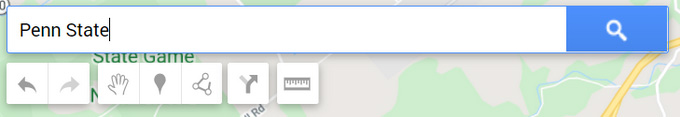

- Using the search bar to the right, you can type in coordinates, addresses, or search for the name of a place you wish to include on your map.

- When you click enter or the search button, the possible results will populate the map and the left layers area.

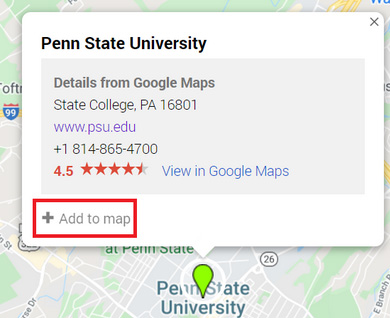

- To add this point to the map, click on the “Add to Map” button.

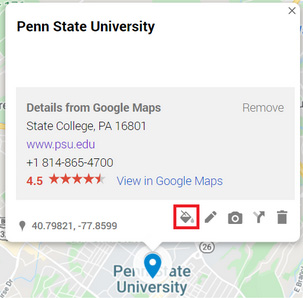

- It adds it to an “Untitled Layer.” We’ll address how to change this next, but first, let’s change the marker for Penn State. To change the symbol, click on the little paint bucket at the bottom. This will allow you to change both the color and the style of the icon.

- I changed the icon from the standard pin to this graduation cap:

- I changed the icon from the standard pin to this graduation cap:

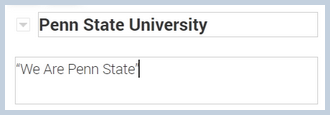

- The pencil next to the paint bucket allows you to change the name in the popup, as well as add a description.

- The camera allows you to add a photograph in case you’d like to showcase some photos of the landscape you are describing.

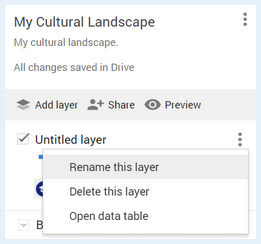

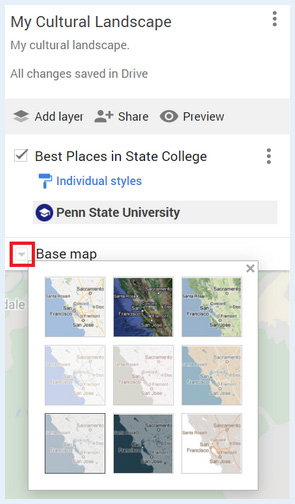

- To change the name of the Layer, left click on the three dots to the right of the layer, and click “Rename Layer”

- You can also change your basemap clicking on the arrow to the left of “Basemap” and making a selection

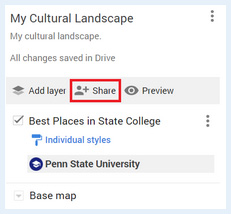

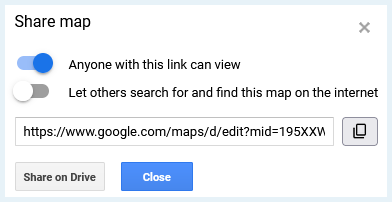

- Once you’ve added all of the places you want, make sure to enable link sharing to your map. To do so, click “Share”

- Then make sure the settings in the 'Share map' window are set to 'Anyone with this link can view' and then close the window.

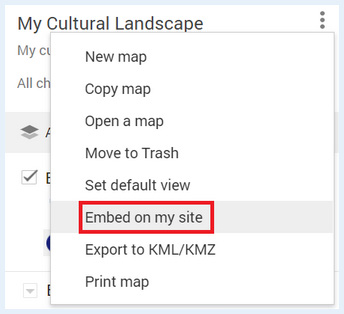

- Once you have made all of your selection for your map and are ready to embed it in your StoryMap, click the three dots to the right of your Map’s Name and select “Embed on my Site”

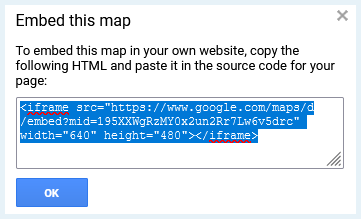

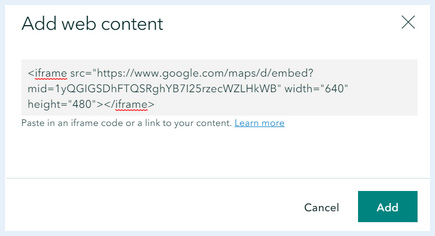

- This will generate a popup with some code. Copy this code.

You will now switch to the ArcGIS Online Portal:

- Sign into Penn State’s ArcGIS Online Portal [34] with your Penn State credentials.

- Click on the square with nine dots to the left of your Name at the top right of window:

- Select StoryMaps from the list of options

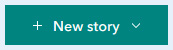

- Select “New story” towards the upper right of the webpage.

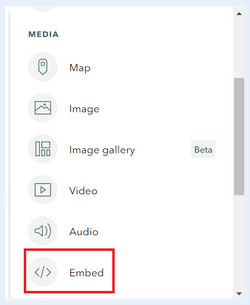

- In your ArcGIS StoryMap, click the plus button to add content. Under the “Media” subheading, click on Embed.

- Paste the code you copied from the 'Embed on my site' step above into the gray box and select “Add”

Your Google MyMap should now be added to your StoryMap.

6.9 Spatio-cultural Analysis Exercise

Introduction

This week’s lesson focuses on reading cultural landscapes. This is not just a theoretical pursuit; it is a means of both collecting and analyzing real-world data that enables one to understand the everyday use of places and the significance that places may hold for people. Individual buildings are tied together by the landscape; the landscape itself is the setting for our daily interactions within a place. Reading the landscape can provide information crucial to a range of intelligence and human security concerns, whether your interest is in determining how to prepare a vulnerable neighborhood for a major hurricane or discover the base of operations of a terrorist cell.

It is also a skill that requires practice in order to fully appreciate what it can reveal about a place. With this assignment, you will choose a landscape, observe it, analyze it in terms of its use and vulnerabilities, and present your findings using StoryMaps as a medium. This assignment is broken down into three parts: fieldwork, analysis, and presentation.

Make sure you read the assignment from start to finish before you begin. You might want to print it and keep it handy as you complete it.

Fieldwork

- Choose a landscape.

Before you begin, choose a landscape to which you have easy enough access that you can spend considerable time observing it. You can choose one with which you are very familiar, one you know in passing, or one that is totally unfamiliar (note that you will notice different things depending on how well you know the area). It can be any kind of landscape — residential, commercial, agricultural; urban, suburban, rural; historic, new, redeveloped — anything is fair game as long as it is a cultural landscape.

Remember that a landscape is a visible portion of Earth’s surface. For the purposes of this assignment, your chosen landscape is not an entire city or neighborhood. Rather, it should be a limited part of these larger places. It should be small enough that you can either:

a) see most of it from a single vantage point, or

b) see it in its entirety in the span of a walk no greater than 10 minutes in length.

Note: Choose a landscape that you can observe at various points during the day (you can — and are encouraged to — do this over several days if necessary). Expect to take photographs and notes as you do your fieldwork.

- Visit and observe.

Visit your chosen landscape three times, for 30-60 minutes each time. Find a good vantage point and use this to observe it. If your landscape requires you to walk through it to fully observe it, take several walks. Try to do this over several days and at different times of day. As you do, jot down some of your field observations. Your observations should incorporate physical, social, and political aspects of the landscape. Below, you will find a list of questions to help focus your observations.

Physical aspects

- What is visible within the landscape? Include things you normally take for granted, such as the style and age of infrastructure, road markings, architectural styles, graffiti, etc.

- What is the condition of the physical features of the landscape? Are they pristine or in disrepair, or somewhere in between? Are there indications that someone is working to take care of the landscape?

Social aspects

- Who is present within the landscape? Consider things like age, gender, race and/or ethnicity, class, and other markers of identity such as clothing styles; pay attention to the languages spoken, the kinds of conversations you overhear, etc.

- What kinds of activities are taking place within the landscape and who is engaging in them?

- How do people, vehicles, and animals move through the landscape? Pay attention to direction and speed of travel, and whether movements are aimless or purposeful.

- Where and why do people pause in the landscape?

Political aspects

- Who is expected to be in this landscape? Consider things like age, race, class, etc. What indicators on the landscape tell you who is expected to be there — e.g., signage, the presence of other people of this group, etc?

- How are people expected to behave in this landscape?

- Do people adhere to, flout, or subvert those expectations? If people flout or subvert the expectations, in what ways? If they tend to adhere, why do they seem to do so?

These last few points, which get at the expectations and social boundaries of the landscape, are sometimes obvious and sometimes not. More obvious indicators include signage barring or granting access to spaces or prohibiting certain behaviors. Be aware that some indicators are less direct, more subtle, or more dynamic (e.g., is there a police presence that keeps out people who appear to be intoxicated? Is everyone so well dressed that someone in casual clothes would stand out? Are there specific groups of people who seem to dominate the space, or groups who are visibly marginal here?).

During your visits, take photos that you think are representative of what you see on the landscape. You may also find it useful to take a notebook and jot down some of your observations.

Analysis

After completing your fieldwork, review your observations. Start developing a profile of the landscape: identify its primary function(s), the kinds of features it includes, and a general description of who uses the landscape and how they use it, and what vulnerabilities are present within the landscape.

In terms of security vulnerabilities, use the following questions to guide your analysis:

- What, if any, threats to human security are relevant to this landscape? Think beyond terrorsim here; you might also consider, for example, whether the infrastructure is vulnerable to things like natural disasters, whether the spatial arrangement facilitates the spread of disease or fire, or makes it easier to hide organized crime.

- What populations, if any, would be at risk from those threats?

- Are there any features on this landscape that have some symbolic value that might be potential targets or foci for security threats?

- If this landscape seems to you to be totally free from threat, why do you think so?

Presentation

Using Google MyMaps and the instructions provided on page 6.7 Introduction to Google MyMaps [35] of this lesson, identify your chosen landscape on a map. Add at least three features that you found significant or interesting.

Create a StoryMap to present your findings. It should include the elements below, logically and coherently organized.

- Embed your Google MyMap depicting the landscape into your StoryMap. Add at least three points of significance to your map with placemarks and label them accordingly.

- At least one photo for each point of significance above.

- At least one photo that provides an overview of the landscape.

- General descriptions of the physical, social, and political aspects of the landscape based on your field observations and the questions posed above.

- An assessment of any security vulnerabilities you find relevant to this landscape, per the analysis instructions above.

Your text should be well-written, logically organized (with appropriate headings), and free from grammatical errors. If you want the practice, you may organize it like you would a written brief. Your text should be no longer than 1,000 words.

Submit your completed StoryMap

When you have completed your StoryMap including all of the associated elements, you need to share your StoryMap. The following steps match the instructions we used in Lesson 1 to share your first StoryMap.

Ensure your StoryMap or Data is shared to the course’s ArcGIS Online Group:

- Go to the metadata page for your story

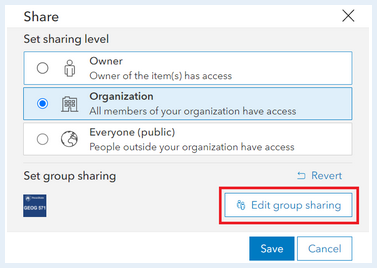

- On the right side click the button 'Share'

- Set the share level to 'Organization' and Set the group settings to the course’s group by clicking 'Edit Group Sharing.' make sure there is a check mark next to the course’s group.

Deliverable:

When you have finished compiling your StoryMap for this assignment and your StoryMap has been 'Published', save the URL for your StoryMap.

The URL for your StoryMap should look something like this:

- https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/223f1885402c44626ad614e5b844c2b4

To submit the URL for your StoryMap exercise, return to the Lesson 6: Cultural Landscapes module in Canvas and look for the Lesson 6 StoryMap Exercise dropbox. The dropbox has instructions for submitting the assignment.

6.10 Summary and Final Tasks

Summary

In this lesson, we discussed at length (and with admittedly ridiculous numbers of images) what cultural landscapes are, what they can tell us, what it means to read them, and some limitations inherent in reading them. Given the length of this lesson, we will briefly recap some major points here.

Actively reading cultural landscapes involves paying attention to things like signage, street names, street plans, infrastructure, monuments, architecture, and the placement of symbolic elements. Successful readings of a given landscape will consider these elements with respect to one another, and will consider the landscape within its broader historical, cultural, social, economic, and political contexts.

Cultural landscapes (or built environments) reflect the local culture, and give us clues as to how they are intended to be used, as well as who is expected to use them. Some features, such as slide or grind marks on rails or benches, or spikes on window ledges, suggest both uses of the space that resist or differ from the official expectations, as well as potential marginalization of certain populations (e.g., homeless people). Landscapes reveal the (historical) values of a given community, though those values may be a better reflection of those embraced by the state or municipal government than by the community itself.

When we read landscapes, it is imperative to remember that all readings are subjective: they reflect our own attunements relative to our individual experiences as well as our memberships within different textual communities. Finally, while cultural landscapes can reveal a great deal about a place, they are sometimes constructed to conceal aspects of the place.

Bearing in mind these caveats, reading the landscape can be productive and informative.

Deliverable:

Please return to the Lesson 6 module in Canvas where you will find the Lesson 6 Discussion Forum which contains the discussion prompt and specific instructions for the assignment.

Please check the Canvas Syllabus or Calendar for specific time frames and due dates.

Final Tasks

Complete all of the Lesson 6 tasks

You have reached the end of Lesson 6! Double-check the to-do list on the Lesson 6 Checklist page [36] to make sure you have completed all of the activities listed there before you begin Lesson 7.

Questions?

If you have any questions now or at any point during this week, please feel free to post them to the GEOG 571 - General Discussion Forum. (That forum can be accessed at any time in Canvas by opening the Lesson 0: Welcome to GEOG 571 module in Canvas.)