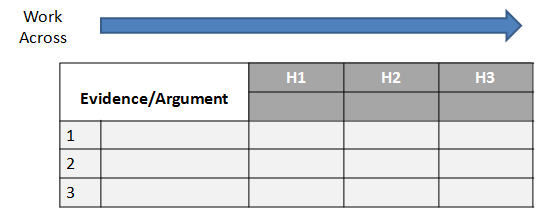

Action 1: Develop Tentative Conclusions. You will now draw tentative conclusions about the relative likelihood of each hypothesis by trying to disprove the hypotheses rather than prove them. The matrix format gives an overview of all the evidence for and against all the hypotheses, so that you can examine all the hypotheses together and have them compete against each other. Previously you analyzed the "diagnosticity" of the evidence and arguments by working down and across the matrix, focusing on a single item of evidence and examining how it relates to each hypothesis. Now, work across and down the matrix, looking at each hypothesis and the evidence as a whole.

Analysts have a natural tendency to concentrate on confirming hypotheses they already believe to be true, and giving more weight to information that supports a favored hypothesis than to information that weakens it. Moreover, no matter how much information is consistent with a given hypothesis, you cannot prove that hypothesis is true, because the same information may also be consistent with one or more other hypotheses. On the other hand, a single item of evidence that is inconsistent with a hypothesis may be sufficient grounds for rejecting that hypothesis.

This step requires doing the opposite of what comes intuitively when evaluating the relative likelihood of alternative hypotheses, by looking for evidence or arguments that enable you to possibly reject the hypothesis or determine that it is unlikely. This follows a fundamental concept of the scientific method of rejecting or eliminating hypotheses, while tentatively accepting only those hypotheses that cannot be refuted. The scientific method obviously cannot be applied without the analyst's intuitive judgment, but the principle of seeking to disprove hypotheses, rather than confirm them, helps to overcome the natural tendency to favor one hypothesis.

In examining the matrix, look at the minuses, or whatever other notation you used to indicate geospatial evidence that may be inconsistent with a hypothesis. The hypothesis with the fewest minuses is probably the most likely one. The hypothesis with the most minuses is probably the least likely one. The fact that a hypothesis is inconsistent with the evidence is certainly a sound basis for rejecting it. The pluses, indicating evidence that is consistent with a hypothesis, are far less significant. It does not follow that the hypothesis with the most pluses is the most likely one, because a long list of evidence that is consistent with almost any reasonable hypothesis can be easily made. What is difficult to find, and is most significant when found, is hard evidence that is clearly inconsistent with a reasonable hypothesis.

This initial ranking by number of minuses is only a rough ranking, however, as some evidence obviously is more important than other evidence, and degrees of inconsistency cannot be captured by a single notation such as a plus or minus. By reconsidering the exact nature of the relationship between the evidence and the hypotheses, you will be able to judge how much weight to give it. Analysts who follow this procedure often realize that their judgments are actually based on very few factors, rather than on the large mass of information that they thought was influencing their views.

Action 2: Apply Judgment: The matrix does not dictate your conclusion. Rather, it should accurately reflect a judgment of what is important and how the evidence relates to the probability of each hypothesis. You, not the matrix, makes the decision. The matrix only organizes your analysis, to ensure consideration of all the possible interrelationships between evidence and hypotheses, and to identify those items that heavily influence your reasoning.

The matrix may show a hypothesis is probable, and you may disagree. If so, it is because you omitted from the matrix evidence or arguments that influenced on your judgment. Go back and add the evidence or argument, so that the analysis reflects your best judgment. Following this procedure will cause you to consider things you might otherwise have overlooked or revise your earlier estimate of the relative probabilities of the hypotheses. When you are done, the matrix serves as an audit trail of your thinking and analysis.

Importantly, this process forces you to spend more analytical time than you otherwise would on what you had thought were the less likely hypotheses. The seemingly less likely hypotheses usually involve more work. What you started out thinking was the most likely hypothesis tends to be based on a continuation of your recalled geospatial experiences and patterns. A principal advantage of the analysis of competing hypotheses to geospatial intelligence is that it forces you to consider the alternatives.

Action 3: Sensitivity Analysis: You should analyze how sensitive your conclusion is to a few critical items of evidence. This is done by considering the consequences for your geospatial analysis if that evidence were wrong, misleading, or subject to a different interpretation. In Step 5, you identified the evidence and arguments that were most diagnostic, and later you used these findings to make tentative judgments about the hypotheses. Now, go back and question the key items of evidence that drive the outcome of the analysis:

- Are there questionable assumptions that underlie your understanding and interpretation?

- Are there alternative explanations or interpretations?

- Could the evidence be incomplete and, therefore, misleading?

If there is any concern at all about denial of information and/or deception, this is an appropriate place to consider that possibility. Look at the sources of key evidence:

- Are any of the sources known to be controlled by a distrusted actor?

- Could the sources have been duped and provided information that was planted?

- Could the information have been manipulated?

Put yourself in the shoes of a deception planner to evaluate motive, opportunity, means, costs and benefits of deception as they might appear to the opponent.

Action 4: Report Your Conclusions. In this step, you may decide that additional research is needed to check key judgments. It may be appropriate to go back to check the original source materials rather than relying on someone else's interpretation. In writing your report, it is desirable to identify critical assumptions that went into your interpretation and to note that your conclusion is dependent upon the validity of these assumptions. If your report is to be used as the basis for decision-making, it is appropriate to provide the relative likelihood of alternative possibilities. Analytical judgments are never certain. Decision-makers need to make decisions on the basis of a full set of alternative possibilities, not just the single most likely alternative. You should consider a fallback plan in case one of the less likely alternatives turns out to be true.

Action 5: Establish Milestones to Monitor. Analytical conclusions are always tentative, therefore, it is important to identify milestones that may indicate events are taking a different course than predicted. It is always helpful to specify things one should look for that suggest a significant change in the probabilities. This is useful for intelligence consumers who are following the situation on a continuing basis. Specifying in advance what would cause you to change your mind will also make it more difficult for you to rationalize such developments as not really requiring any modification of your judgment.