Leasing Phase

Leasing privately held mineral rights is a complex process, both from the industry and landowner side. The U.S. is unique in having private ownership of mineral rights by the landowner, whereas in all other countries the government holds rights to mineral extraction, including oil and gas. In the United States, the oil and gas leasing process is not government regulated and thus takes the form of a legal contract between the landowner (the lessor) and the energy company (the lessee). The purpose of a lease is to convey the rights of exploration and production to an E&P company, often referred to as the operator, in exchange for the landowner/mineral right's owner receiving lease payments until drilling occurs and royalties from any oil or gas produced on the land. The leasing process typically begins with a "landman" representing an operator approaching a landowner to offer terms that would ideally benefit both the landowner/oil and gas right's owner and the operator. Since lease agreements involve significant amounts of money and are legally complex, one should obtain advice from an attorney who has expertise in oil and gas leasing. Energy companies have detailed knowledge of the best locations to drill for oil and gas and are offering money, therefore they tend to have significant leverage in negotiating leases, however, savvy landowners have the ability to make favorable deals, both financially and with terms and conditions. Surface owners leasing subsurface minerals can, through a well-constructed contract, protect crops, livestock, buildings, personal property, access and any other aspects of their surface holding for the duration of a lease. It should be noted that a company cannot drill beneath someone's property without a signed lease. Although lessees will often accept significant revisions to their standard lease or sales contract, they can reject them and no drilling and production rights are conveyed, nor is any financial gain to the landowner.

The common components of a lease include:

- Length of the lease: Typical leases grant an energy company drilling rights for five years, however, any period of time can be written into the lease. Often times a lease may contain language that gives the energy company options on renewing leases.

- Lease payment terms: Companies and landowners will typically come to payment terms based on how much a company will pay for drilling rights per acre over the duration of the lease, often referred to as the primary term of the lease.

- Royalty rates: Once a well or wells are drilled and fractured, the primary terms of the lease have been met and the landowner will now receive royalties based on the production of oil, gas, and other hydrocarbons. The royalty rate, which is a specified percentage of the oil and gas-generated revenues that is paid to the landowner, is a minimum of 12.5% by law in Pennsylvania but can be negotiated upward by the landowner.

- Other terms and conditions: A landowner can negotiate a variety of terms and conditions that are site-specific, such as where the company can drill or install infrastructure, payments for land or crop disturbance, etc.

This Landowner's Guide to Oil and Gas Leasing in Pennsylvania provides a great summary of considerations that should be taken into account when considering a lease and provides an example lease.

The leasing rates for acreage vary widely in space and time. It was common for leasing rates to be on the order of several dollars an acre and royalty rates at the state minimum of 12.5% of oil and gas revenues for many decades in Pennsylvania prior to the discovery of the Marcellus shale's productivity. In the late 2000s the leasing rates in some areas of Pennsylvania sky-rocketed to greater than $5,000 per acre with royalty rates going as high as 20% once it was discovered just how prolific a Marcellus shale well's production could be. These lease and royalty rates occurred during the initial boom of the Marcellus shale but have since decreased back to several hundred to several thousand dollars per acre with lease rates between 12.5-15% depending on location and how critical the land is to an energy company's land holdings portfolio.

These lease rates sound like a lot of money, especially for a large landowner, just think if you were a dairy farmer with 100 acres and were offered $5,000 per acre, that's a half million dollars! Well, think about being that same dairy farmer getting 15% royalties on a well that may produce 10 billion cubic feet of gas over a decade of time when gas is $3 per million cubic feet. That's 15% of $30 million dollars or $4.5 million dollars (minus taxes and deductions) for that farmer over the course of time, you have to sell A LOT of milk to make that kind of money! So most of the time the royalties a landowner receives from oil or gas production is significantly more than the lease payments. There are many financial and legal factors to take into consideration when entering into a lease agreement, which is why it is always a good idea to get the advice of a good oil and gas attorney and financial planner to make sure any oil or gas development on a person's land works to their advantage. There are certainly many examples where landowners feel they were taken advantage of by the energy companies, so the landowner needs to be aware of potential pitfalls, get everything in writing, and read the fine print before signing a lease agreement. This video discusses some of the landowner benefits associated with leasing their oil and gas rights.

Video: Tom Murphy, Potential Landowner Benefits (00:57)

Dave Yoxtheimer: As a landowner, what might be some of the potential benefits you could recognize if Shale wells were drilled on or beneath your property?

Tom Murphy: We find with unconventional shale gas development, as it's occurring in Pennsylvania and beyond, certainly in the United States, where landowners owned their minerals, the primary benefit is economic. So landowners, again if they own their minerals, and they're approached by a company, they'll potentially lease those same minerals. They'll receive a payment for that lease, as its put together, and structured, and signed. And then potentially, if a well is drilled, royalties could accrue. And again, a portion of those would go back to the landowners as well. So again, the primary benefit that most landowners encounter when unconventional natural gas development occurs is in economic.

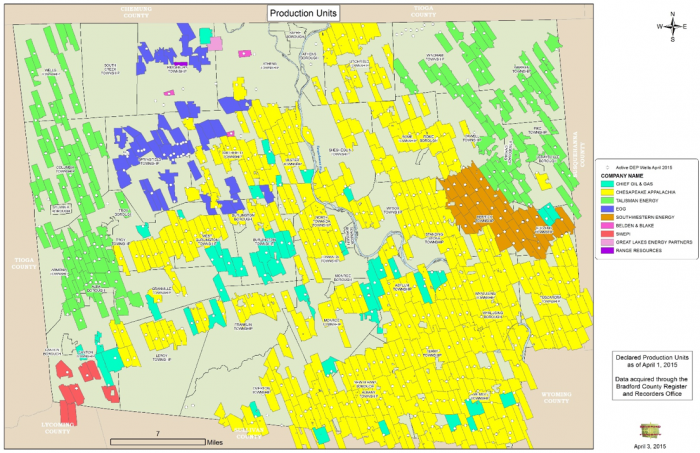

Once a company has determined they are interested in drilling in a given area, they will attempt to lease up as much land in that area for drilling as they feel is necessary to meet their project goals. The more contiguous the lease area the better for the company as it allows the company to more efficiently develop the oil and gas resources without having to "skip" over areas. Depending on the area of interest and the amount of available land, companies may lease up to tens to hundreds of thousands of acres which may give them several hundred drilling locations to work with over the course of years. Once a company has selected a well site or sites, the leased landowner's parcel will be included in a "drilling unit", which is an area of land typically one or two square miles (640 or 1,280 acres, respectively). Any revenues generated from& oil, gas and other hydrocarbons produced from wells in a given drilling unit will be totaled, and then royalties will be paid to landowners based on how much acreage they have leased in that drilling unit and what royalty rate is in their lease. For example, if Farmer Jones has 160 acres within a 640 acre (one square mile) drilling unit, he would get one quarter (160 divided by 640 acres) of the royalties for that drilling unit. If in a given month 100 million cubic feet of gas were produced from wells contained within a drilling unit and gas is $3 per thousand cubic feet, then a total of $300,000 dollars of gas revenues were generated, 15% of which is payable as royalties to the landowners in that unit. Therefore the landowners get approximately $45,000 to split up as the royalty pool, and Farmer Jones gets 25% of those royalties based on the amount of his leased land in that drilling unit...that's $11,250 a month, not too shabby! Energy companies may deduct expenses to produce the gas so the landowner may get less depending on the claimed expenses, which should be negotiated in the lease. The figure below shows the drilling units for Bradford County, Pennsylvania which is one of the most heavily drilled counties for the Marcellus shale gas. Note that multiple companies have leased land in Bradford County, but that their leased area is fairly contiguous based on the drilling units.

It is important to note that a lease does not automatically entitle an energy company to drill on a property. The company must first obtain a drilling permit from the state regulatory authority (in PA this is the Department of Environmental Protection), which requires a detailed plan for drilling a specific target formation as well as permits for constructing well pads, water sourcing, among other phases. The permitting process ensures regulatory protections and makes the drill site subject to state laws and inspections, which we will explore in the next section.