A Familiar History of Water and Population Growth

In the mid-1800s, early settlers named the area "Las Vegas", Spanish for "the meadows", because the Valley, fed by the Las Vegas Springs, was lush, grassy, and green. The springs yielded approximately 5,000 acre-feet of water per year. As you may recall, this is about the amount of water needed today to support 5,000 families of four, or a population totaling around 20,000. With a plentiful natural water supply, Las Vegas became a key stop and hub for the railroads: first the San Pedro, LA, & Salt Lake City Railroad, and later the Union Pacific.

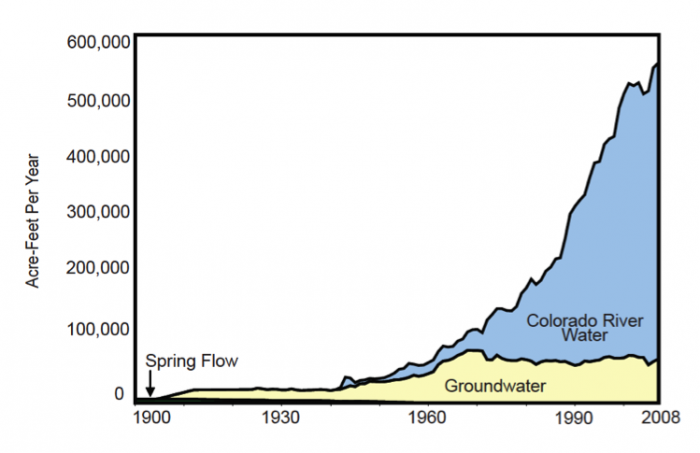

In the early 1900s, private wells drilled into the valley-fill confined aquifer became commonplace to augment the spring flows, as residents tried to turn the valley into productive farmland. Many of the wells were artesian but were left uncapped (Figure 7). By 1912, the 1000 residents of Las Vegas withdrew about 22,000 acre-feet of water per year from the springs and aquifer. By 1930, a combination of several dry years and increasing demand led to overdraft conditions. In the meantime, the Colorado River Compact of 1922 allocated a small amount of Colorado River water to Southern Nevada (see Sidebar: CO River Compact). However, Las Vegas continued to rely principally on groundwater, and aside from some industrial uses, the Colorado allotment went largely unused until the 1940s. (Note that Hoover Dam, the primary infrastructure that allows surface water storage and withdrawal for Clark County, was not completed until 1936.)

With a steadily growing population and water demand, withdrawals greatly exceeded natural recharge and overdraft of the aquifer worsened. In an effort to reduce groundwater extraction, the Las Vegas Valley Water District was created in 1947, in part to begin using the Colorado River allotment. Despite these efforts, by 1960 the valley’s population had swelled to over 110,000, and almost 50,000 acre-feet of water were extracted from the aquifer annually. The natural springs dried up in 1962, and sustained overdraft led the potentiometric surface to drop by a few feet per year on average. The pattern continued through 1971 until the Southern Nevada Water System began delivery of Colorado River water from Lake Mead for municipal supply – 24 years after the water district was created.

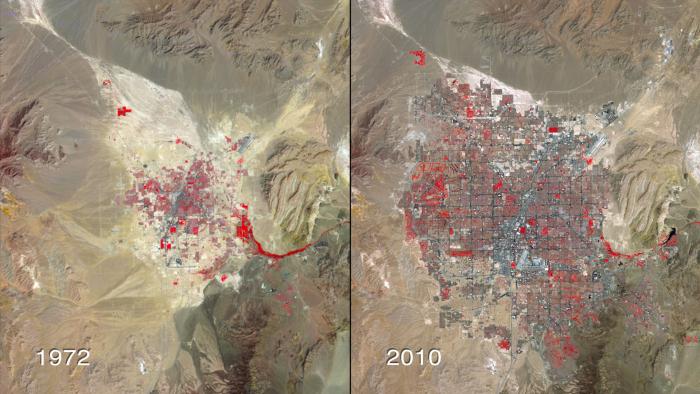

With a plentiful supply (300,000 acre-feet per year) of Colorado River Water ready for delivery and distribution, population growth accelerated, reaching almost 700,000 by 1990 (Figure 8), and about 2 million by 2012. Coincident with the shift to water supply from Lake Mead in 1971, dependence on groundwater gradually started to decline (Figure9). As discussed in more detail below, managed (induced) recharge of the groundwater system using surplus Colorado River water was begun on a small scale in the late 1980s; this “banking” of water in wet years or times of surplus is viewed as one strategy to cope with water shortages.