7.2.1: Open Pit Mining

Open pit mining almost always applies to non-coal materials, mostly metal and aggregate mining. However, near-surface steeply dipping coal seams are extracted using open pit mining. Reclamation, i.e., returning the land to an acceptable standard of productive use of the open pit mine is deferred until the mine closes. Let’s look a few diagrams to better understand the relationship between the suitability of open pit mining and the spatial characteristics of the deposit.

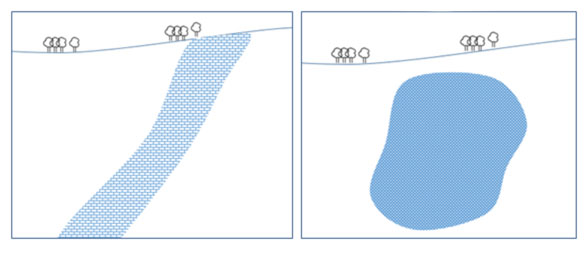

On the right side, you can see a massive deposit, and on the left, there is a steeply pitching deposit.

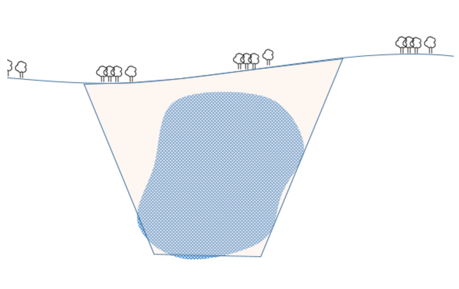

Now, try to imagine the way that mining should proceed to extract the ore in each case. You may think of the “open pit” as a huge upside down cone that is superimposed onto each deposit. In the case of the deposit on the right side, we would have this.

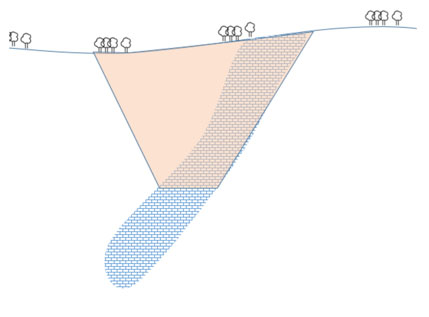

In the case of the steeply dipping deposit on the left, our open pit would look more like this.

These diagrams also provide insight on the reason that reclamation has to be delayed until the end of the mine life. Simply put: we start mining from the surface and work our way, level by level, down into the deposit. If we were to return the waste material to the place where we mined it, we would block access to the ore in the lower levels.

Did you notice in the diagram of the steeply pitching deposit, the pit bottom stopped well before reaching the end of the orebody? As we go deeper, our stripping ratio will eventually become prohibitively large. Moreover, as we go deeper, mining costs, other than stripping, will increase also. For example, the time and cost to transport ore from the lower levels of the pit to the processing plant will increase to the point at which we will have to buy additional trucks to maintain production levels. When we reach the point where the cost to recover the ore exceeds its value, we have two major choices: begin the mine closure stage of the mine’s life; or begin an underground mining operation. The latter is common in metalliferous deposits. Of course, that point may not be reached for decades, as the depth of the pit may exceed 2000’ in some cases.

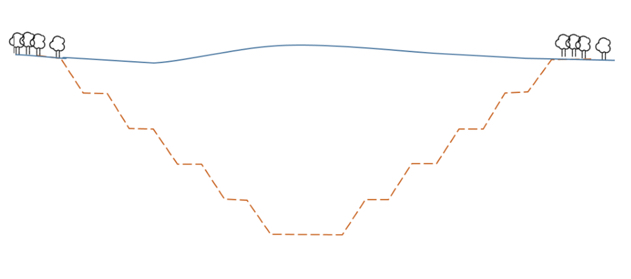

In the previous diagrams, I illustrated the sides of the pit with a straight line. Open pits cannot be operated in this way. Instead, the pit walls need to step down, which provides access to the pit by people and equipment, and it provides a working platform at each level. We refer to these steps as benches, and this diagram is a more accurate representation of the pit than are the previous ones.

The number of benches will depend on the bench height and the ultimate pit depth. In the last lesson, the concept of slope stability was introduced, and that will weigh heavily in the decision of the number of benches, their dimensions, and the angle of the pit wall. It is incumbent on the mining engineers to ensure sure that slope instabilities will not occur throughout the mine life, as we discussed in the last lesson.