Mother Politics: Anti-colonial Nationalism and the Woman Question in Africa by Joyce M. Chadya, Journal of Women's History 15.3 (2003) 153-157:

All nationalisms are gendered, . . . they represent relations to political power . . . legitimizing, or limiting, people's access to the rights and resources of the nation state.– Anne McClintock

Anne McClintock's comment on nationalism succinctly captures the position of women during anti-colonial nationalism on the African continent. Across the continent, especially following World War II, women played a crucial role in the ousting of colonial/apartheid minority governments. However, the top leadership of most, if not all, of the nationalist movements was exclusively male. There was, therefore, a gender bias right from the creation of nationalist movements. This scenario was to be replicated in independent Africa when most of the senior government posts were (and continue to be) held by men. Women still find themselves at the margins of political and economic decisions at the party and government levels.

Locating Women During Wartime

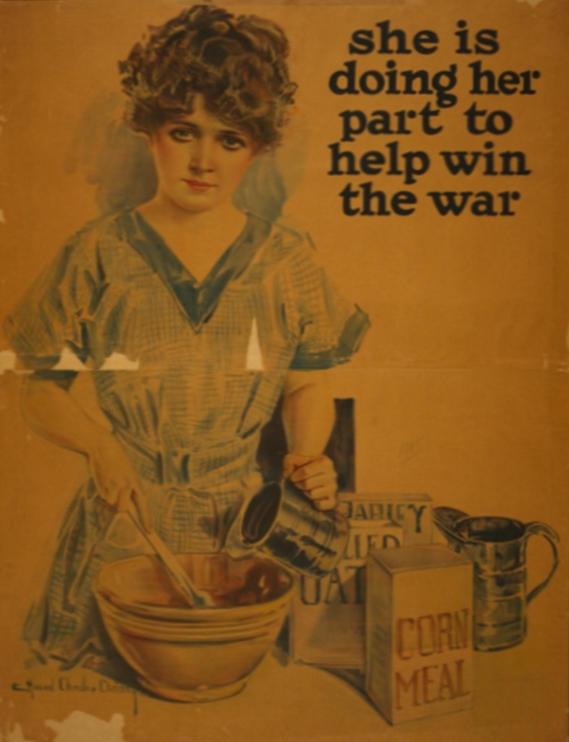

Gendered divisions of labor have historically placed women in the private or domestic spheres—as homemaker, nurturer, and educator. During wartime, women are called upon to serve the nation through constructions of these gendered identities as you see in the following propaganda posters:

Thus, a woman’s role in the private sphere is utilized to create a sense of national unity, rallying for the cause of war. Sending their husbands, sons, and fathers off to war, women are encouraged to support the national war agenda through their consumer choices (or ability to ration said choices), domestic habits and production, and so forth.

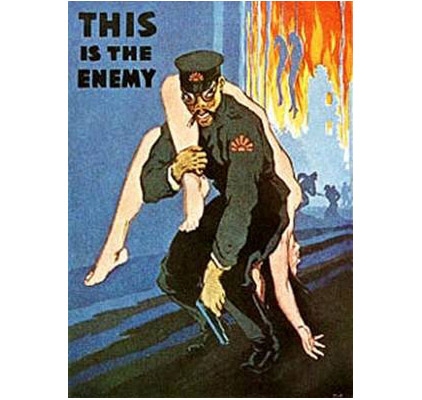

The purported vulnerability of women to the enemy is also part of the rally to war. The figure below presents an image of a naked and seemingly unconscious woman being carried away by a caricature of a Japanese soldier. Such wartime propaganda utilizes gendered constructions of female vulnerability and purity in conjunction with a depraved, immoral enemy to embolden our soldiers and allies to act in defense of the defenseless.

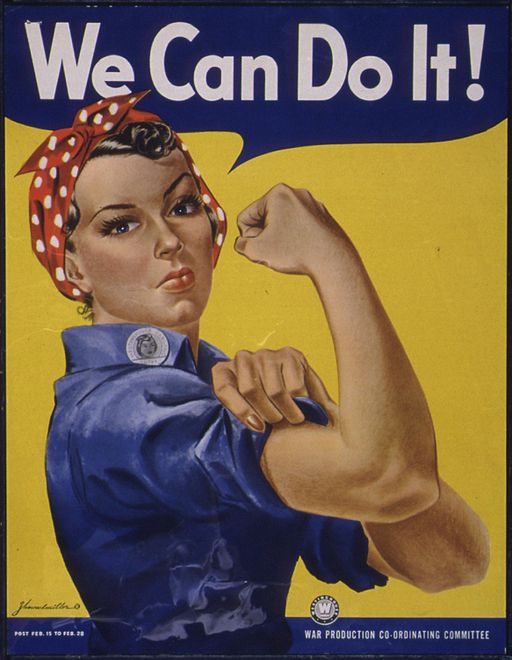

Nationalism during war can work to temporarily disrupt gendered divisions of labor as well. As in the case of Rosie the Riveter (figure below) and the women featured in the Hollywood Film A League of their Own, women are called upon to fill traditionally male roles and occupations in an effort to also help with the war effort.

While these transgressions of traditional gender roles do temporarily offer women opportunity to participate more fully in the public sphere, once the war is over and the men come home, women are thanked for their service to country and directed back to the domestic/private sphere.

NARRATOR: Girls playing pro ball? You bet. Back in 1943 when the boys went off to war, baseball and chewing gum tycoon Bill Wrigley decided to keep the parks filled by creating the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. Even though the league lasted for 12 seasons, very few people knew about it.

[BACKGROUND YELLING]

Now, director Penny Marshall brings us the long overdue story of these remarkable girls of summer in Columbia Pictures' new comedy, A League of Their Own. The all-star lineup includes Tom Hanks as the manager, the catcher, Geena Davis, the pitcher, Lori Petty.

LORI PETTY: I made it, a Rockford Peach.

NARRATOR: The scout, Jon Lovitz.

JON LOVITZ: Are you coming? See, how it works is the train moves, not the station.

NARRATOR: Rosie O'Donnell at the hot corner, and batting cleanup, Madonna.

ANNOUNCER: No wonder they call her All the Way Mae.

PRODUCER: 189 Charlie, take one, aim one.

PENNY MARSHALL: There were scouts going around. They went around to various factory leagues and softball leagues. They were made to try out in Wrigley Field. It started with four teams, 16 girls on a team, and drafted them.

JON LOVITZ: Hey.

GEENA DAVIS: Hey yourself.

JON LOVITZ: I saw you playing today. Not bad. Not bad. You ever hear of Walter Harvey? Makes Harvey Bars.

GEENA DAVIS: Yeah. I feed them to the cows when they're constipated.

JON LOVITZ: He's starting a girls' baseball league. Want to play?

GEENA DAVIS: Huh?

JON LOVITZ: Nice retort. It's a real league, professional.

LORI PETTY: Professional baseball?

JON LOVITZ: They'll pay you, 75 dollars a week.

LORI PETTY: We only make 30 dollars at the dairy.

JON LOVITZ: Well, then, this would be more, wouldn't it?

GEENA DAVIS: My sister and I are both picked for the team. And we feel like misfits a little bit, you know, like we have this skill that we have never had anything to do with. And then this amazing thing comes along, this baseball leagues, that gives us in a way to fulfill ourselves.

MADONNA: What are you looking at?

ROSIE O'DONNELL: Yeah, what are you looking at?

LORI PETTY: All these girls going to be in the league?

[CHUCKING]

MADONNA: You know, they got over 100 girls here, so, um, some of yous are going to have to go home.

ROSIE O'DONNELL: Yeah, sorry about that.

MADONNA: Come on, Doris.

ROSIE O'DONNELL: Some people are jerks.

LORI PETTY: What do you mean, some of us?

MADONNA: Do it. OK, some of them are going home. Hey,

ROSIE O'DONNELL: How did you do that?

SPEAKER 1: One of the problems that we had right off the bat was finding girls that had some ability on the baseball diamond. That was a long process. We screened an awful lot of girls.

PENNY MARSHALL: Out here in Los Angeles, they said the batting cages never did so much business. Every actress in town was at the batting cage, hitting the balls.

TOM HANKS: This is the best gig to be in a position where I get paid to come and put on a uniform and run around the ball field as much as I want to. It's a man's fantasy baseball experience.

GEENA DAVIS: Well, yeah. We have a very funny scene in the movie where he's been a bad coach to us. So I sort of have taken over. And I give all the signs and do the coaching basically. Tom doesn't like the play that I've called. So we're giving opposing signs and things. It was fun.

TOM HANKS: Hey, who's the damn manager here? am.

GEENA DAVIS: Then act like it, you big lush.

ROSIE O'DONNELL: Ho, ho, ho, ho. You tell him, Dottie.

TOM HANKS: Play ball. I play Jimmy Dugan, six time National League home run champion. He hates being here. And he doesn't want to be here. And he's not going to take it seriously. And.

[CRYING]

Are you crying? Why are you crying? There's no crying in baseball.

PENNY MARSHALL: Let me see what happens, Rosie and Madonna.

MADONNA: I actually never played baseball my entire life. So I had to start from scratch. I have a problem that it's that I have a lot of years of dance training. And Penny was always screaming at me that I was playing baseball like a dancer.

TOM HANKS: In the early going, yeah, her throwing technique was pretty much-- it was a choreographed step, step, kick, fling kind of thing.

MADONNA: I'm going to kill Tom for saying that about me.

TOM HANKS: But she's better now.

PENNY MARSHALL: I had teamed her up with Rosie O'Donnell. I said, OK, you two are going to be best friends in the movie. So get to know each other.

MADONNA: What if at a key moment in the game, my uniform bursts open. And oops, my bosoms come flying out.

ROSIE O'DONNELL: You think there are men in this country who ain't seen your bosoms?

PENNY MARSHALL: Cut. Nice.

ROSIE O'DONNELL: She's OK. There's my girl. You're all right. Every so often, she starts acting like a big superstar, you know, big pop movie icon, star celebrity, singer thing. And that's when, you know, Penny looks at me and goes, Rosie, take her down. Bam, right down. She's humbled.

MADONNA: Rosie is a great baseball player like. And I just, I'm so glad she's here, because she coaches me on everything.

ROSIE O'DONNELL: Now I'll show you how.

MADONNA: OK.

[LAUGHTER]

ROSIE O'DONNELL: You know, I'm working on it. We've got about five more weeks. I'm thinking I'll have it done by the end of the--

PENNY MARSHALL: She was a real good sport. She worked so hard. She would run every morning. Then she'd work out playing ball. Then at night, she'd jitterbug.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

SPEAKER 2: The official stance of the league was that they had no social life, that they would-- it was basically a convent. The girls were sent to charm school. Not too patronizing, right?

INSTRUCTOR: Gracefully and grandly. Gracefully and posture.

SPEAKER 2: They had people from Helena Rubinstein come out, give them all new hairdos.

INSTRUCTOR: And sit, right over left. Legs are always together. A lady reveals nothing.

[GIGGLING]

LORI PETTY: It was just hysterical to me. But that was really important in the '40s, that you're, you know, a lady. And a lady reveals nothing. They played three games in two days. And they always had to take all these showers and set their hair. And they were all curly, because they had to be all pretty.

TRACY REINER: Oh, for God's sake.

LORI PETTY: And it's just the love and the dedication that they had for baseball.

TOM HANKS: Uh, Lord. I'd just like to thank you for that waitress in South Bend. You know who she is. She kept calling your name.

ROSIE O'DONNELL: OK.

TEAM: Go Peaches!

[MUSIC - "CHOO CHOO CH' BOOGIE]

ANNOUNCER: Unbelievable! Full house audience.

Times have certainly changed since World War Two and women are now more fully a part of the public sphere. Indeed, they are part of our military, police and fire fighting forces. Nonetheless, the full inclusion of women into these spheres (and of men into the domestic/private sphere) without stigma or bias, still has some ways to go.

Women in the US Military

Watch this video (10:40) which explores the changing role of women in the US military.

Core beliefs of militarism are:

- that armed force is the ultimate resolver of tensions;

- that human nature is prone to conflict;

- that having enemies is a natural condition;

- that hierarchical relations produce effective action;

- that a state without a military is naïve, scarcely modern, and barely legitimate;

- that in times of crisis those who are feminine need armed protection;

- that in times of crisis any man who refuses to engage in armed violent action is jeopardizing his own status as a manly man.

And expanding upon these concepts, Bernazzoli and Flint (2010), assert that militarization also requires a connection of these ideas to national identity, patriotism and moral right. They extend the core beliefs of militarism to include:

- that soldiers possess certain values and qualities that are desirable in civil society;

- that military superiority is a source of national pride;

- that those who do not support military actions are unpatriotic;

- that those who do not support military actions are anti-soldier;

- that for a state to engage in armed conflict is to serve the will of a divine being.

In this section, it should be much clearer how gender, nationalism, and geopolitical codes have been constructed and strategically deployed.