It may seem like the basic attachment of location information to anything and everything reveals a relatively stable future for Geography and Geospatial technology. All we have to do is Geotag everything and we’re done with this Geospatial Revolution thing, right? I don’t think it’s that simple, because the enormous potential of location-enabled everything faces similarly huge barriers for people who want to make sense of interconnected and massive spatial data sources. Moreover, the super-simple common format for a location—one set of coordinates on the Earth—completely fails to describe the richness of Geography.

For starters, it’s often impossible to assign a single relevant location to an observation. Let’s even take something as constrained as a Tweet as an example. You only have 140 characters on Twitter to tell your story, so not much can happen here with locations, right? Wrong. There are multiple relevant locations with any Tweet. Where is the Twitter user from? Where were they when they Tweeted their message? What about the message itself? Does it contain references (explicit or implicit) to locations? We’ve done some research on this area at Penn State and found that many Tweets contain references to many different locations. So how do we show that on a map? Which ones are the most important or explanatory? Like most complex analytical problems, the answer may depend a lot on what you’re trying to learn from that information. Let’s say you’re working for a crisis management organization and you want to monitor what’s happening on Twitter to identify emerging concerns in the wake of a major disaster. What types of locations would you want to see? Could you use location information to establish a basis for comparing the credibility of a particular report? How would you show millions of these reports on maps that could be used by a normal human being who isn’t just studying this stuff after the fact?

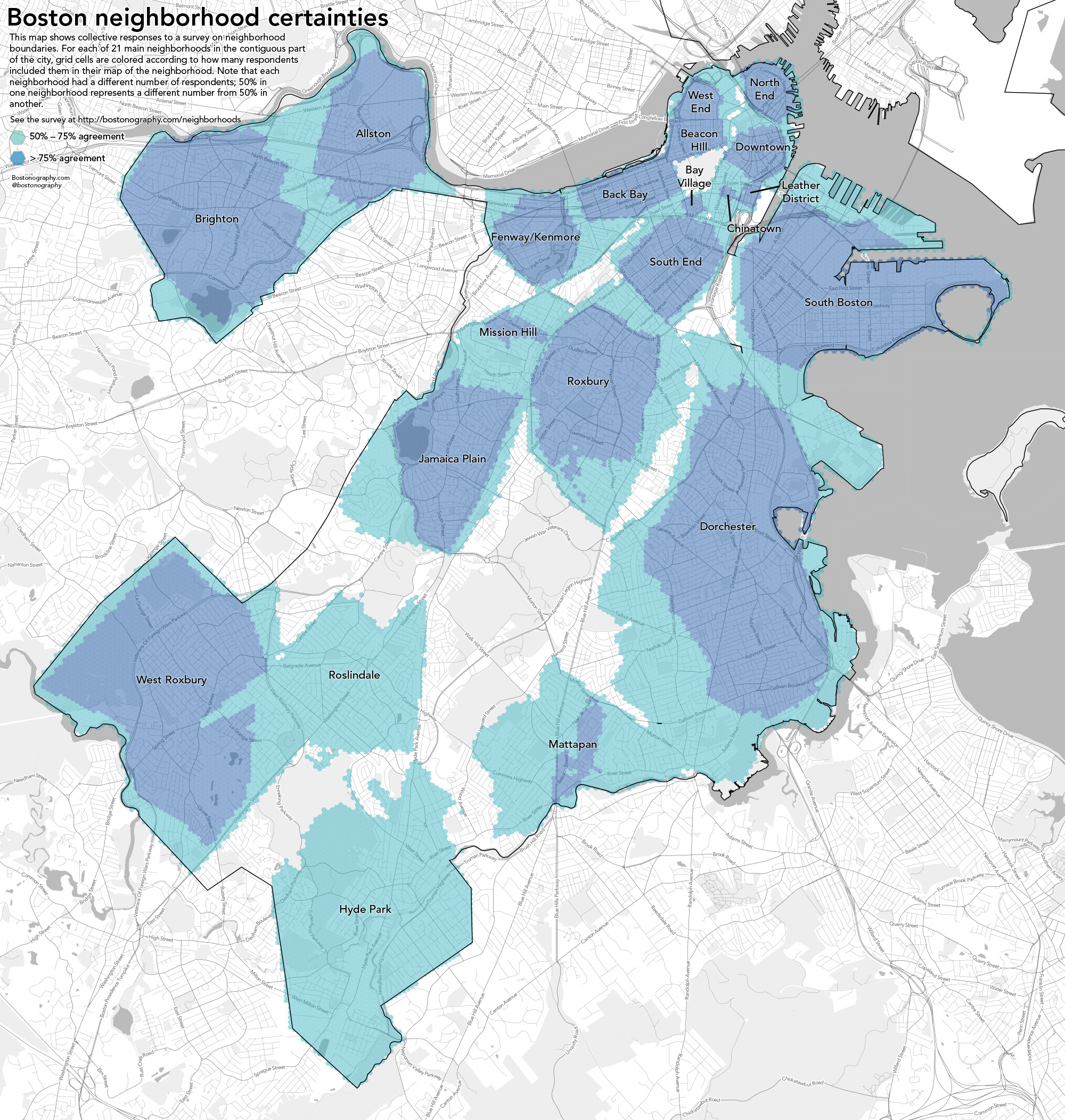

In the more benign example here, which places are relevant to this important discussion on where to find a delicious Cinnabon cinnamon roll? The United Kingdom, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Austin are all mentioned here explicitly. But what about the hometowns for each of these folks, or the place where Cinnabon is headquartered (Yumtown at the corner of Godhelpme Ave. and Gimmeicing Lane)?

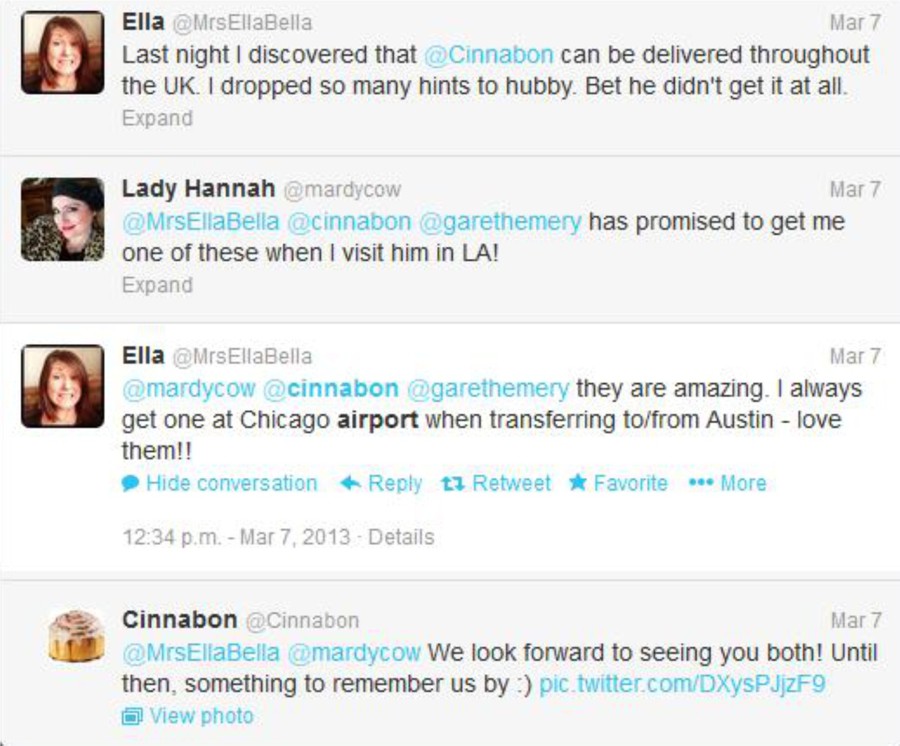

While we’re at it, let’s talk about defining locations more broadly as well. Until now I’ve emphasized a single point in space as a location. Geographic locations can include well-defined formal regions like states and counties, natural areas like watersheds and mountain ranges that can sometimes be formally defined by their observable features, and ill-defined cultural regions like neighborhoods. I live in a place informally known as Happy Valley. It’s not just the city of State College or its surrounding townships and boroughs. It includes space outside of those formal areas, and it cannot be defined precisely despite the fact that it clearly corresponds to a place on Earth. We still have a lot to learn about how to collect people’s conceptions of these sorts of places and use them on maps. The example here by Andy Woodruff and Tim Wallace at Bostonography.com shows how people in Boston conceive of their city’s neighborhoods. It’s pretty blobby and imprecise, and parts of the map are empty. This is a much more faithful representation of what we can actually know about these types of places than the neat and tidy borders we can define for legal boundaries.