It is Sherman Kent, who has been described as the "father of intelligence analysis", that is often acknowledged as first proposing an analytic method specifically for intelligence. The essence of Kent’s method was understanding the problem, data collection, hypotheses generation, data evaluation, more data collection, followed by hypotheses generation (Kent, S. 1949, Strategic intelligence for American world policy, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.).

Richards Heuer subsequently proposed an ordered eight step model of “an ideal” analytic process, emphasizing early deliberate generation of hypotheses prior to information acquisition (Heuer, R. 1981, "Strategies for analytical judgment," Studies in Intelligence, Summer, pp. 65-78.):

- Definition of the analytical problem

- Preliminary hypotheses generation

- Selective data acquisition

- Refinement of the hypotheses and additional data collection

- Data intervention and evaluation

- Hypotheses selection

- Continued monitoring

Heuer’s technique has become known as Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH). The technique entails identifying possible hypotheses by brainstorming, listing evidence for and against each, analyzing the evidence and then refining hypotheses, trying to disprove hypotheses, analyzing the sensitivity of critical evidence, reporting conclusions with the relative likelihood of all hypotheses, and identifying milestones that indicate events are taking an unexpected course. The use of brainstorming is critical since the quality of the hypotheses is dependent on the existing knowledge and experience of the analysts, since hypotheses generation occurs before additional information acquisition augments the existing knowledge of the problem. ACH is widely cited in the intelligence literature as a means for improving analysis. The primary advantage of ACH is a consistent approach for rejection or validation of many potential conclusions (or hypotheses).

Heuer acknowledges how mental models, or mind sets, are essentially the re-representations of how analysts perceive information (Heuer, Richards J. Jr. & Center for the Study of Intelligence 1999, Psychology of intelligence analysis, Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, Washington, DC.). Even though every analyst sees the same piece of information, it is interpreted differently due to a variety of factors (past experience, education, and cultural values to name merely a few). In essence, one's perceptions are morphed by a variety of factors that are completely out of the control of the analyst. Heuer sees mental models as potentially good and bad for the analyst. On the positive side, they tend to simplify information for the sake of comprehension, but they also obscure genuine clarity of interpretation.

ACH has evolved into an eight-step procedure based upon cognitive psychology, decision analysis, and the scientific method. It is believed to be particularly appropriate for establishing an audit trail to show what an analyst considered and how they arrived at their judgment. (Heuer, Richards J. Jr. & Center for the Study of Intelligence 1999, Psychology of intelligence analysis, Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, Washington, DC.).

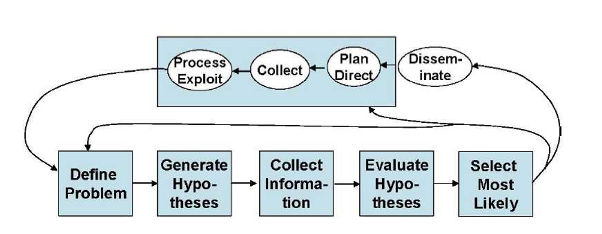

Heuer’s approach is the prevailing view of the analysis process. Figure 1 by the 2002 Joint Military Intelligence College (JMIC) illustrates the integration of the fundamentals of ACH into the intelligence process (Waltz, E. 2003, Toward a MAUI NITE intelligence analytic process model, Veridian Systems, Arlington, VA.).

Figure 1 is particularly significant since it shows the intelligence cycle steps of:

- planning and direction,

- collection,

- processing,

- analysis, and

- dissemination

Which incorporates the following analytic process steps within the analysis steps:

- define the problem,

- develop hypotheses,

- collect information,

- evaluate hypotheses, and

- select the most likely alternative.

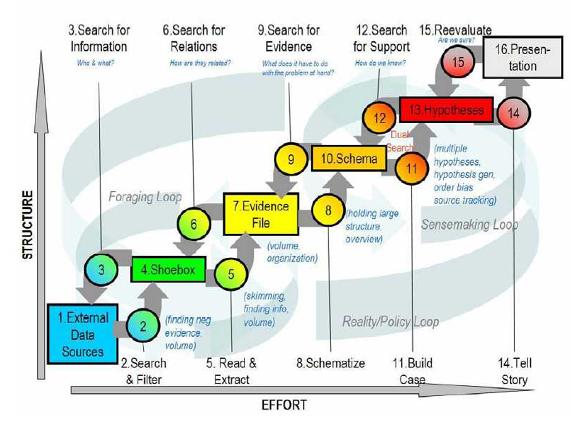

Since Heuer’s development of ACH, another model of the intelligence analysis process is proposed by Pirolli in 2006 which was derived from the results of a cognitive task analysis of intelligence analysts (Pirolli, P.L. 2006, Assisting people to become independent learners in the analysis of intelligence: final technical report, Palo Alto Research Center, Inc., Palo Alto, CA.). The analytic process is described as “A Notional Model of Analyst Sensemaking,” with the cognitive task analysis indicating that the bottom-up and top-down processes shown in each loop are “…invoked in an opportunistic mix.” (Pirolli, P. & Card, S.K. 2006, The sensemaking process and leverage points for analyst technology identified through cognitive task analysis, Palo Alto Research Center, Inc., Palo Alto, CA.). Figure 2 illustrates this process./p>

The term “sensemaking” is used as a term to describe the analysis process.Sensemaking is defined “…as the deliberate effort to understand events,” describing the elements of sensemaking using the terms “data” and “frame.” A frame is “…an explanatory structure that defines entities by describing their relationship to other entities” (Klein, G., Phillips, J.K., Rall, E.L. & Peluso, D.A. 2007, "A data-frame theory of sensemaking" in Expertise out of context, ed. R.R. Hoffman, pp. 113-15). The Klein article further explains that “The data identify the relevant frame, and the frame determines which data are noticed. Neither of these comes first. The data elicit and help to construct the frame; the frame defines, connects and filters the data.”

Pirolli and Card contend that many forms of intelligence analysis are sensemaking tasks. As figure 2 illustrates, such sensemaking tasks consist of information gathering, re-representation of the information in a schema that aids analysis, the development of insight through the manipulation of this representation, and the creation of some knowledge based on the insight. The analyst proceeds through the process of:

They also suggested that the process may be reversed to:

In other words, in terms of Figure 2, the process can be a mix: top-down and/or bottom-up.

Schemas are the re-representation or organized marshaling of the information so that it can be used more easily to draw conclusions. Pirolli and Card note that the re-representation “may be informally in the analyst’s mind or aided by a paper and pencil or computer-based system” (Pirolli, P. & Card, S.K. 2006, The sensemaking process and leverage points for analyst technology identified through cognitive task analysis, Palo Alto Research Center, Inc., Palo Alto, CA.).