Working Conditions

Creating Sustainable Working Conditions Worldwide

While some of us could associate "sustainable working conditions" with compensation, benefits, diversity and the like, I would like us to focus our attention specifically on working conditions at the most basic level: workers are not beaten, they have the right to leave and quit on their own accord, and they have an expectation of safe working conditions. Basically, sustainable working conditions are to ensure that people are treated as humans regardless of where they work. Unfortunately, even in this day, this is not happening worldwide, and we do see some striking occasions of history repeating itself. In many cases, the repetition we see are some of the struggles facing workers in the United States in the 1800s-1900s being relived today in places like China and Bangladesh.

Today, with the worldwide prevalence of the internet and nearly a quarter of the world's population owning smartphones, poor working conditions and worker abuses are far more likely to be captured in realtime and disseminated instantly to a worldwide audience. Informed and aware consumers are also more likely to place pressure on those international companies operating in these countries to improve working conditions, and, as a result, many of the sustainability efforts of garment and electronics companies with offshore operations place heavy emphasis on working conditions in their supply chains. As we will see in the specific case of Nike, the reputational damage is swift in action and lasting in impact.

Working Conditions: History Repeating Itself

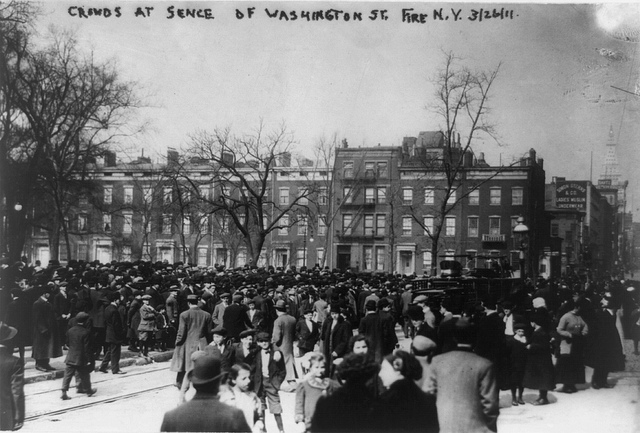

1911: New York City, USA

It was the deadliest workplace accident in New York City's history. On March 25th, 1911, a deadly fire broke out in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York's Greenwich Village. The blaze ripped through the congested loft as petrified workers–mostly young immigrant women–desperately tried to make their way downstairs. By the time the fire burned itself out, 146 people were dead. All but 17 of the dead were women and nearly half were teenagers.

The workers in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory were among the hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers who toiled in the city's garment factories at the time. They came from countries such as Italy and Russia in search of a better future, and all around them they saw the riches promised by the American Dream. New York was in its Gilded Age and the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory was not too far from the limestone mansions of millionaires and the elegant shops of the famed Ladies Mile. Two men who had achieved the dream were the wealthy owners of the thriving Triangle factory. Isaac Harris and Max Blanck, immigrants who had arrived from Russia only 20 years earlier, had become known as New York's "Shirtwaist Kings," and each owned fully staffed brownstones on Manhattan's Upper West Side.

[...]

When a tossed match or lit cigarette ignited a fire on the eighth floor of the building, flames spread quickly. Blanck and Harris received warning by phone and escaped, but the 240 workers on the ninth floor continued stitching, oblivious to the flames gathering force on the floor below. When they finally did see the smoke, the women panicked. Some rushed toward the open stairwell, but columns of flames already blocked their path.

A few workers managed to cram onto the elevator while others ran down an inadequate fire escape, which crumbled under the weight, crashing to the ground almost 100 feet below. The only remaining exit was a door that had been locked to prevent theft. The key was tucked into the pocket of the foreman, who listened to the women's cries for help from the street. Hundreds of horrified onlookers arrived just in time to see young men and women jumping from the windows, framed by flames.

In the days that followed, a temporary morgue near the East River was set up for families to identify the bodies of their loved ones. Nearly 400,000 New Yorkers filled city streets to pay tribute to the victims and raise money to support their families. The ensuing public outrage forced government action. Within three years, more than 36 new state laws had passed regulating fire safety and the quality of workplace conditions. The landmark legislation gave New Yorkers the most comprehensive workplace safety laws in the country and became a model for the nation.

2013: Savar, Bangladesh

From Manik and Yardley, 2013:

A building housing several factories making clothing for European and American consumers collapsed into a deadly heap on Wednesday, only five months after a horrific fire at a similar facility prompted leading multinational brands to pledge to work to improve safety in the country’s booming but poorly regulated garment industry.

By early Thursday, the Bangladeshi news media reported that at least 142 people died in the rubble of Rana Plaza, a building in Savar, an industrial suburb of Dhaka, the capital. Police officials put the death toll at 134, with more than 1,000 of 2,500 workers injured, many of them still trapped. Soldiers, paramilitary police officers, firefighters and other citizens clawed through the wreckage, searching for survivors and bodies.

Brig. Gen. Ali Ahmed Khan, head of the National Fire Service, said that an initial investigation found that the Rana Plaza building violated codes, with the four upper floors having been constructed illegally without permits.

“There was a structural fault as well,” General Khan added, noting that the building’s foundation was substandard.

The collapse followed a fire in November that killed 112 workers making shorts and sweaters for export and that led importers, including Walmart, to vow to do more to ensure the safety of factories where goods they sell are manufactured. The building collapse on Wednesday quickly revived questions about the commitment of local factory owners, Bangladeshi officials and global brands to provide safe working conditions.

The Bangladeshi news media reported that inspection teams had discovered cracks in the structure of Rana Plaza on Tuesday. Shops and a bank branch on the lower floors immediately closed. But the owners of the garment factories on the upper floors ordered employees to work on Wednesday, despite the safety risks.

Labor activists combed the wreckage on Wednesday afternoon and discovered labels and production records suggesting that the factories were producing garments for major European and American brands. Labels were discovered for the Spanish brand Mango, and for the low-cost British chain Primark.

Activists said the factories also had produced clothing for Walmart, the Dutch retailer C & A, Benetton and Cato Fashions, according to customs records, factory Web sites and documents discovered in the collapsed building.

[...]

“The front-line responsibility is the government’s, but the real power lies with Western brands and retailers, beginning with the biggest players: Walmart, H & M, Inditex, Gap and others,” said Scott Nova, executive director of Worker Rights Consortium, a labor rights organization. “The price pressure these buyers put on factories undermines any prospect that factories will undertake the costly repairs and renovations that are necessary to make these buildings safe.

The final death toll of the Rana Plaza accident would be more than 1,100.

Offshore, But No Longer Out of Mind

In some cases, what makes countries like China and Bangladesh attractive to low-cost offshoring are the same factors which can make them dangerous for workers: few environmental regulations, little concern for worker safety, lax enforcement, and little fear of worker litigation. Regardless of if a factory in one of these countries is complying with local regulations, it is becoming more and more common for companies to hold all factories in their supply chain–domestic or foreign–responsible to meet standards which may be far more stringent than any local law. The reason for these stringent standards is that the companies with offshore production are being made painfully aware of the tremendous financial and reputational risk of being associated with "sweatshops" or factories with substandard–or deadly–working conditions. In the case of Rana Plaza, brands such as Walmart, Benetton, and The Children's Place were linked to past or current production at the factory, and the public reaction was by no means positive.

Few brands want to have images of their logo and clothing tags associated with working conditions that left 1,100 dead. Needless to say, the primary and secondary reputational damage to a brand from such an occurrence could be significant.

An example of offshore facilities being held to newly stringent standards happened just after the Rana Plaza tragedy, when the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh and other international auditing initiatives specific to the garment industry in Bangladesh were created. In the case of the Accord, signatory companies from around the world agreed to support and help share costs for what would act as a private international regulatory body working within Bangladesh. Some notable signatories include Puma, Abercrombie & Fitch, Helly Hansen, and H&M. The Accord's primary charter is to audit, inspect, and report on the working conditions of factories in order to create CAPs, or Corrective Action Plans.

To provide some scope of the current working conditions present, in one inspection of 1,326 factories, it found a staggering 95,293 structural, electrical, and fire hazards. In the specific case of structural failure as happened in Rana Plaza, the Accord found that "Most buildings are not constructed in accordance with the structural design drawings. In just over 10% of the factories inspected, this resulted in an immediate requirement to reduce the loads in the building, such as storage, water tanks and other weight" (Accord, p.7).

Supply Chain Auditing Becoming the Norm

With the tremendous reputational risk of being associated with "sweatshops," intensive, unannounced supply chain auditing is becoming the norm in some industries, with consumer electronics, shoe, and garment production being among the most intensive. It would also seem that the responsibility is so serious that these companies do not rely on self-reporting or even local auditing capabilities... many go to significant effort and expense to execute all international audits with dedicated staff from headquarters to ensure valid, consistent inspection without potential for bribery or conflicts of interest.

We will delve more into this topic later in this lesson, specifically in examining the GRI aspects and indicators related to working conditions. As we will see in the case of Nike, there are many opportunities for companies to make real, deep, immediate impacts to improve working conditions if they commit to action.