Whistleblower Anonymity and Protection

Documentation is Not Action

In a public SEC filing dated Tuesday, June 3, 2008, a company's CEO referred to a document called "Winning With Integrity: Our Values and Guidelines for Employee Conduct," which read like a proto-sustainability report. It covered the code of conduct in a plainspoken and straightforward manner, and included straightforward "Do" and "Don't" guidance. It was a powerfully worded piece, including passages such as:

It all comes down to personal responsibility–mine, yours, and all of ours–for the way we work and conduct ourselves as [company] employees. Winning with integrity requires a commitment by every member of the [company] team. I know I can count on all employees to do their part; you have my commitment to do the same. [...]

The Winning With Integrity guidelines are organized by major themes: Personal Integrity, Integrity in the Workplace, Integrity in the Marketplace, Integrity in Society and Our Communities, and Integrity Toward the Environment.

In a 19 page document, it would use the word "integrity" 67 times.

It is a document which addresses themes found in many Codes of Conduct as nested into sustainability reports. The language could come from almost any CSR of a major corporation, as it reflects many common themes, guidance items, and areas of emphasis. To put it bluntly, this document could be found within practically any Fortune 500 company. In this specific case, the company is General Motors.

Two years after this specific document was released, the death of a 29 year old woman related to a defective ignition switch and findings from the ensuing lawsuit would lead to one of the most visible product recalls in American history. As the recall, lawsuits, and congressional hearings would progress, reports of internal whistleblowers–in some cases years before–would begin to arise. In some of those cases, the whistleblowers were believed to have been either suppressed, ignored, or both.

We need look no further than some of the headlines over the last year to see some of the impacts of suppressing potentially negative information:

"GM Ignition Switch Death Claims Rise to 67"

"GM Whistleblower was told to 'not find every problem,' report says"

"GM Officials Ignored Alert on Car Stalling"

"Just How Much Will the Recall Storm Cost GM?"

"Attorney Says Legal Action Against GM will Continue"

While we may be making ourselves dizzy shaking our heads with righteous indignation at GM's failure to elevate the early signs of a major engineering flaw, we should each take a moment to introspect and be honest with ourselves:

This could happen anywhere.

Maybe the scope and scale would be far smaller, maybe it wouldn't result in deaths, but these types of situations can happen anywhere. All it takes is one person or a very small group of people. Perhaps even more disconcerting is that the actor's position within the company doesn't matter: It could be a line worker not reporting a chemical-contaminated batch at a food processing facility out of fear for their job, it could be a product quality inspector overlooking flaws so that a time-crunched factory could meet its production targets, it could be a CEO hiding negative findings to elevate share value.

Consider that if even five employees were directly complicit in the General Motors ignition issue, this would represent some 0.00024% of General Motors employees. Put in physical terms, if you were to fill the average bathtub with water, those employees would represent one fifth of one drop. Such is the potential toxicity of a tiny fraction of the whole.

In the efforts to encourage honest, and potentially anonymous whistleblowing, it is essential for one to realize that the goal is not to necessarily persuade or otherwise move masses of people, it is to provide the pathways and process to enable a single person to call attention to a dangerous situation they otherwise might not.

How Sustainability Relates to Whistleblower Protection and Anonymity

While whistleblower protection may seem to be one very tactical concern in the very broad field of sustainability, consider the types of issues on which a whistleblower could report, and the direct impacts to sustainability aspects:

| Potential issue raised | Sustainability aspect |

|---|---|

| Financial fraud or misappropriation | Profit: Overall health and financial viability of the organization |

| Illegal disposal of chemicals | Planet: Responsible disposal and use of hazardous materials |

| Forced overtime and other improper labor practices | People: Fair labor practices and working conditions |

| Changes in important materials or safety specifications | Planet: Potentially dangerous chemicals; People: Potentially unreported hazards to employees or customers |

| Use of sweatshops or child labor | People: Working conditions |

While some may consider whistleblower programs and measures to ensure anonymity as little more than an evolution of the trusty "Comment Box," The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners offers an interesting forensic view on the importance and impacts of whistleblowers and programs designed to facilitate anonymous whistleblowing. Below are a few whistleblower related tables and commentaries from the 2014 version of their fascinating Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse:

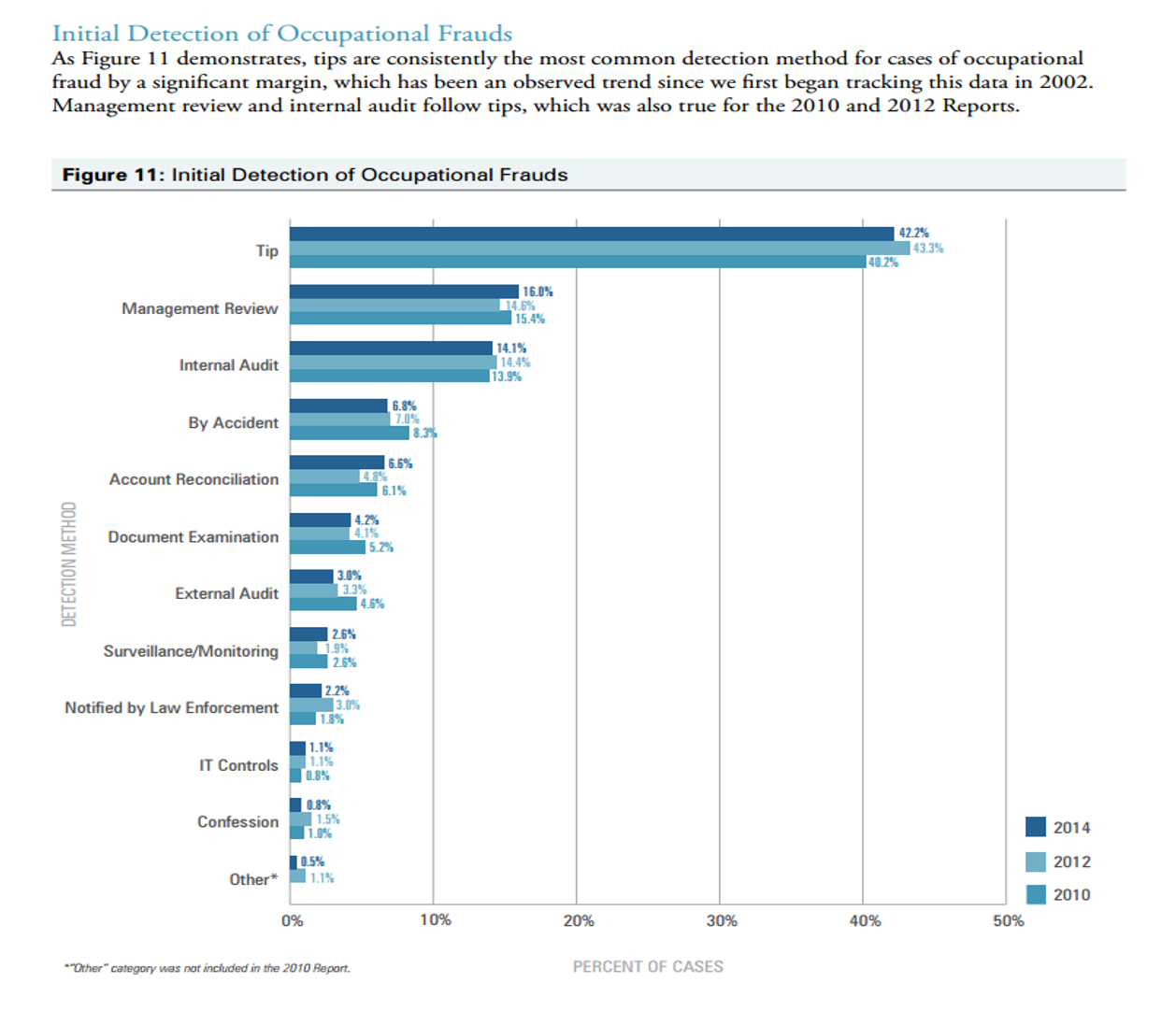

Figure 11: Initial Detection of Occupational Frauds

As Figure 11 demonstrates, tips are consistently the most common detection method for cases of occupational fraud by a significant margin, which has been an observed trend since we first began tracking this data in 2002. Management review and internal audit follow tips, which was also true for the 2010 and 2012 reports.

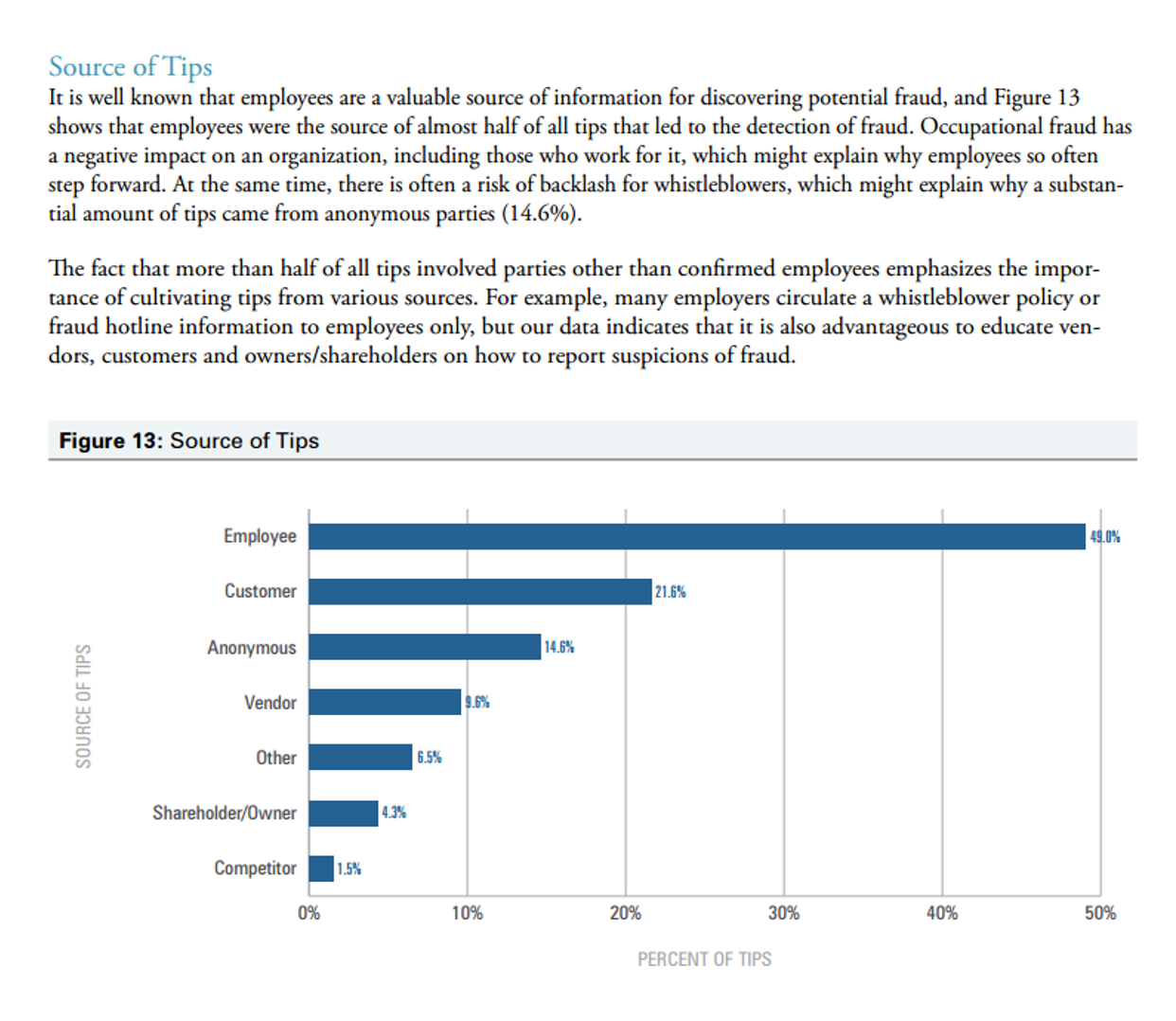

Figure 13: Source of Tips

It is well known that employees are a valuable source of information for discovering potential fraud, and Figure 13 shows that employees were the source of almost half of all tips that led to the detection of fraud. Occupational fraud has a negative impact on an organization, including those who work for it, which might explain why employees so often step forward. At the same time, there is often a risk of backlash for whistleblowers, which might explain why a substantial amount of tips came from anonymous parties (14.6%).

The fact that more than half of all tips involved parties other than confirmed employees emphasizes the importance of cultivating tips from various sources. For example, many employers circulate a whistleblower policy or fraud hotline information to employees only, but our data indicates that it is also advantageous to educate vendors, customers, and owners/shareholders on how to report suspicions of fraud.

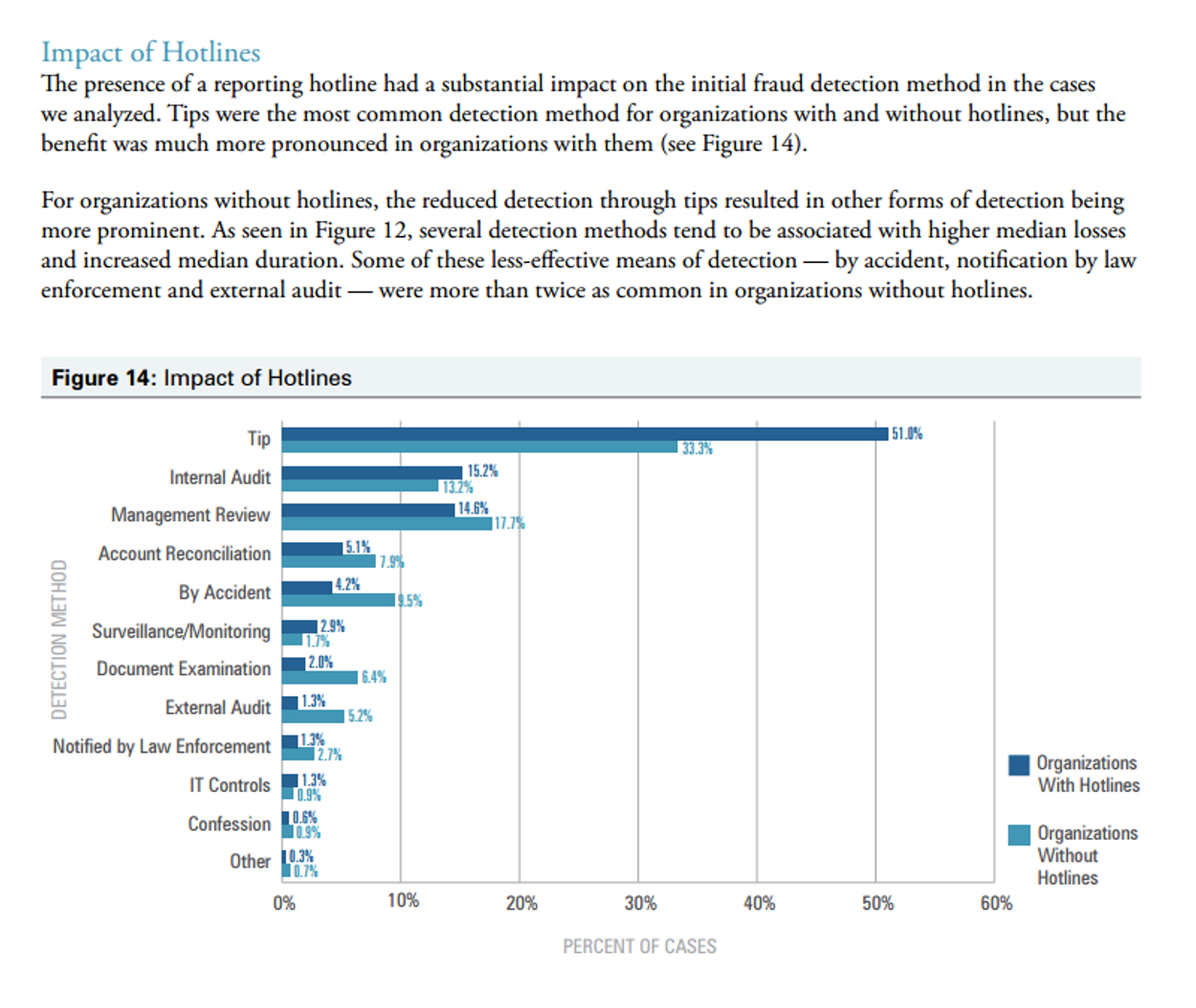

Figure 14: Impact of Hotlines

The presence of a reporting hotline had a substantial impact on the initial fraud detection method in the cases we analyzed. Tips were the most common detection method for organizations with and without hotlines, but the benefit was much more pronounced in organizations with them (see Figure 14).

For organizations without hotlines, the reduced detection through tips resulted in other forms of detection being more prominent. Several detection methods tend to be associated with higher median losses and increased median duration. Some of these less-effective means of detection - by accident, notification by law enforcement, and external audit - were more than twice as common in organizations without hotlines.

Although many of the cases in which we are interested may not necessarily be considered "fraud," it could be expected that the same reporting and whistleblowing mechanisms unearthing fraud within the organization would similarly unearth any potentially damaging issue facing the organization.

A Brief View of Organizational Practices to Facilitate Whistleblowing

Credit: From Ravishankar, 2003:

Steps for Creating a Whistleblowing Culture

Create a Policy

A policy about reporting illegal or unethical practices should include:

Formal mechanisms for reporting violations, such as hotlines and mailboxes.

Clear communications about the process of voicing concerns, such as a specific chain of command, or the identification of a specific person in the organization, such as an ombudsman or a human resources professional.

Clear communications about bans on retaliation.

In addition, a clear connection should exist between an organization's code of ethics and performance measures. For example, in the performance review process, employees can be held accountable not only for meeting their goals and objectives but also for doing so in accordance with the stated values or business standards of the company.

Get Endorsement From Top Management

Top management, starting with the CEO, should demonstrate a strong commitment to encouraging whistleblowing. This message must be communicated by line managers at all levels, who are trained continuously in creating an open-door policy regarding employee complaints.

Publicize the Organization's Commitment

To create a culture of openness and honesty, it is important that employees hear about the policy regularly. Top management should make every effort to talk about the commitment to ethical behavior in memos, newsletters, and speeches to company personnel. Publicly acknowledging and rewarding employees who pinpoint ethical issues is one way to send the message that management is serious about addressing issues before they become endemic.

Investigate and Follow Up

Managers should be required to investigate all allegations promptly and thoroughly, and report the origins and the results of the investigation to a higher authority. For example, at IBM, a long-standing open-door policy requires that any complaint received must be investigated within a certain number of hours. Inaction is the best way to create cynicism about the seriousness of an organization's ethics policy.

Assess the Organization's Internal Whistleblowing System

Find out employees' opinions about the organization's culture vis-à-vis its commitment to ethics and values. For example, Sears conducts an annual employee survey related to ethics. Some questions are: Do you believe unethical issues are tolerated here? Do you know how to report an ethical issue?