Introduction

Cross Examining the Witness

Stated preference methodologies are not necessarily a cleanly and distinctly defined set of research tools, they are instead unified by the fact that they rely on gleaning insight, quite literally, from a test audience's "statements." Most commonly in our application, this test audience will be one or more groups of target customers whom we think could create the foundation of the purchase and use of our final offering.

As we will see in the following lesson, the questions underlying stated preference models can sometimes take on the feel of a courtroom examination on paper, and one could consider the goals to be somewhat similar at times. Stated preference models will sometimes ask the participant several very similar questions in hopes of finding any inconsistencies. They may ask what could be considered confusing or overly hypothetical questions in hopes of revealing your inclinations.

These mechanisms are by design, and lie at the heart of stated preference models, as they tend to be highly dependent on very specific research design and statistical analysis. We will be asking the witness batteries of related questions, and then statistically analyzing the results across a statistically significant number of witnesses.

Flawed Recall

One of the weaknesses of stated preference methods is, indeed, that they rely on statements as opposed to actions. These methods rely on not just the participant's recall of their own actions (which are famously biased and subject to post-rationalization), but on their hypothetical decisions on hypothetical products presented in isolation and purchased with hypothetical money participants hypothetically have.

You can perhaps see but a glimmer of a methodological weakness here.

If participants' self reporting was indeed highly accurate, consider the extension of the concept: products and businesses utilizing these methodologies in their offering research would indeed never fail, as there would be no financial risk or uncertainty. They would but simply send out batteries of surveys, and have consumers tell them exactly how much revenue they can expect.

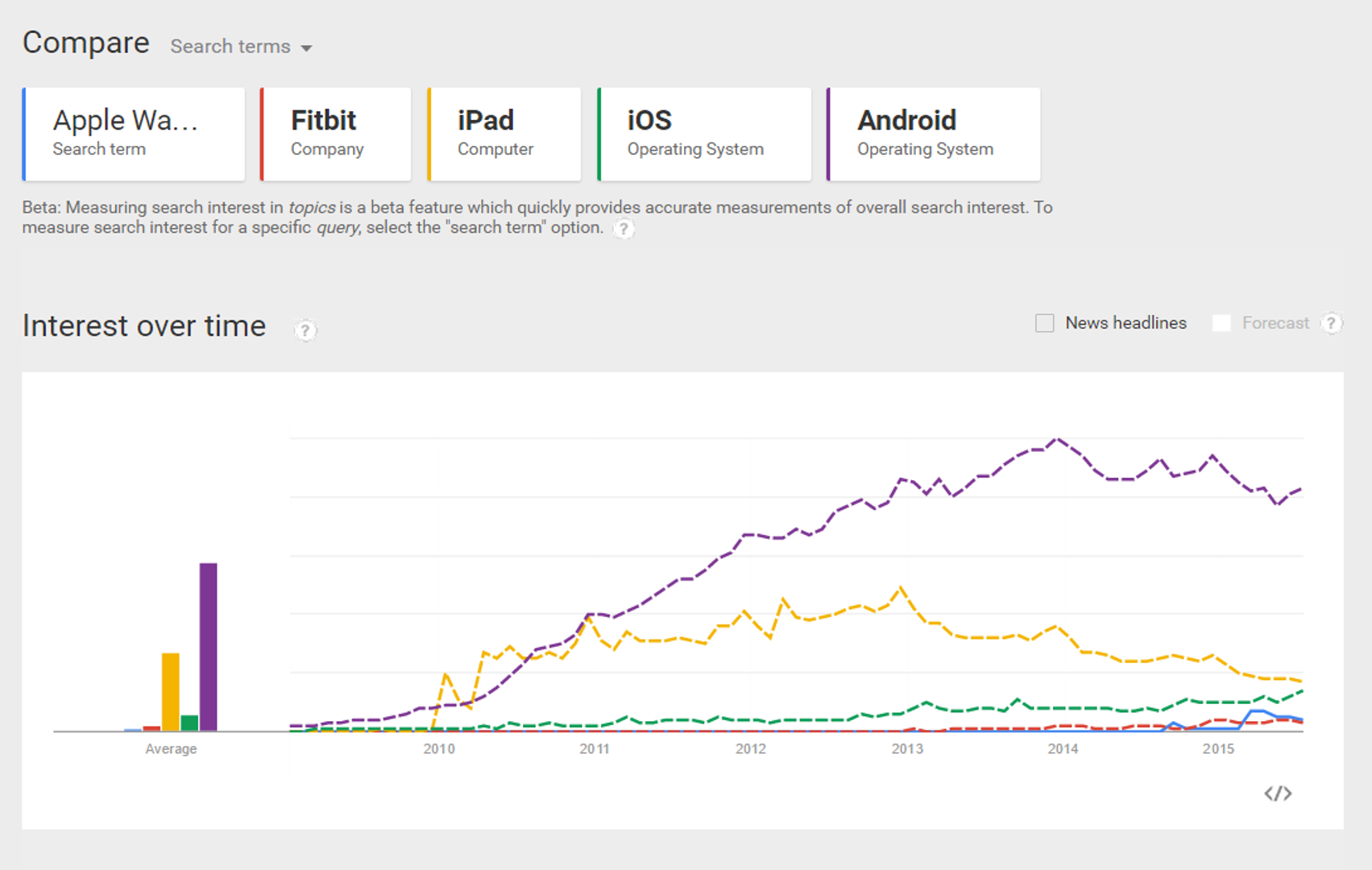

If that were the case, the below would never happen to a company like Apple, the world's 5th largest corporation, upon the release of the Apple Watch:

The fact that one of the most touted product releases from Apple in the past decade (2014 revenue: $183 billion) is struggling to create the same level of interest of a far more limited product from a company .04% the size of Apple (Fitbit estimated 2014 revenue: $754 million), or that sales have dropped 90% since release week, is likely something that Apple did not forecast.

And make no mistake, Apple is arguably one of the most successful companies on the planet, especially in regard to innovation, supply chain, forecasting, and new product rollout.

Biased Witnesses

Sustainability-driven innovation specifically faces a unique set of obstacles in stated preference research, and that is the social pull of sustainability creating positive social approval bias in participants. In essence, what this means is that if someone sees sustainability as socially desirable, they will likely self-report their willingness to engage in sustainability-related behaviors and purchases that they actually would partake in "in the real world." In considering the tremendous social influence sustainability can have on people, this is a very real research concern for us in developing sustainability-driven offerings.

To provide some context for how much influence this may have, consider the influence of social approval bias in something as simple as reporting how many fruits and vegetables you consumed the day before.

From "Effects of social approval bias on self-reported fruit and vegetable consumption: a randomized controlled trial" by Miller et al. [emphasis is mine]:

Methods

A randomized blinded trial compared reported fruit and vegetable intake among subjects exposed to a potentially biasing prompt to that from control subjects. Subjects included 163 women residing in Colorado between 35 and 65 years of age who were randomly selected and recruited by telephone to complete what they were told would be a future telephone survey about health. Randomly half of the subjects then received a letter prior to the interview describing this as a study of fruit and vegetable intake. The letter included a brief statement of the benefits of fruits and vegetables, a 5-A-Day sticker, and a 5-A-Day refrigerator magnet. The remainder received the same letter, but describing the study purpose only as a more general nutrition survey, with neither the fruit and vegetable message nor the 5-A-Day materials. Subjects were then interviewed on the telephone within 10 days following the letters using an eight-item FFQ and a limited 24-hour recall to estimate fruit and vegetable intake. All interviewers were blinded to the treatment condition.

Results

By the FFQ method, subjects who viewed the potentially biasing prompts reported consuming more fruits and vegetables than did control subjects (5.2 vs. 3.7 servings per day, p < 0.001). By the 24-hour recall method, 61% of the intervention group but only 32% of the control reported eating fruits and vegetables on 3 or more occasions the prior day (p = 0.002). These associations were independent of age, race/ethnicity, education level, self-perceived health status, and time since last medical check-up.

Using Research Intelligently

That said, there is not a research methodology in existence which does not have significant flaws or limitations. The key for us is to understand the limitations of each methodology and be intelligent in the use of additional research methods to create a well-rounded understanding of the offering.

There are a few significant functional advantages to stated preference methodologies:

- They are time and cost efficient.

- You do not need to have a final product, making it useful for testing product renderings or even concept statements.

- You can change or modify proposed offerings and retest.

- It can provide a useful set of boundaries to guide your decision making in later phases.

- When statistically significant, findings can provide an initial "gate" for the offering development process.