Dealing with Drought

Short Version: Drought or other natural disasters can cause even really smart people to fail badly if they don't get enough help. However, with plenty of fossil-fueled tools and trade, the dangers of natural disasters have been reduced greatly. Here, we consider two cases of people responding to severe droughts — one before the age of fossil-fuel energy, the other during the age of fossil-fuel energy.

Friendlier but Longer Version: We could tell many stories about the benefits of fossil fuels. Here is one. The details of this story are not especially important, but the basic idea is greatly important—our ability to use fossil fuels to power our tools makes us much better off.

A few years ago, a great group of Penn State students, faculty, and film professionals toured many of the national parks of the US southwest. We hiked to the bottom of the Grand Canyon, rafted the Colorado below the Glen Canyon dam, slept on the slick rock at Canyonlands, and otherwise had a truly wonderful trip.

Many of us were especially fascinated by Mesa Verde. Ancestral Puebloan (often called Anasazi) people lived at that site for roughly 700 years—much longer than the history of the Americas since Columbus—first on top of the mesa, but then moving to build intricate dwellings in caves down the mesa sides, commuting up ladders and steps carved in the rock to work the fields on top. But, after most of a millennium, the people left.

Archaeological sites are almost always open to interpretation and argument. We know what was left behind, and we can learn much of what was going on around the area, but the record is necessarily incomplete and viewed through the lens of who we are.

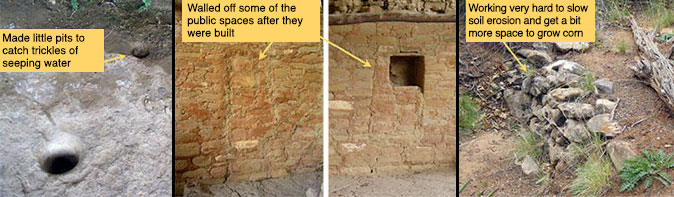

Still, much of the Mesa Verde story is rather clear. The national park rangers showed us the little holes that the people painstakingly carved in the rock in the dwelling caves to capture a trickle of water. We marveled at the carefully constructed check dams, stones set to stop the erosion of the mesa top and catch a little soil and water to grow a little more corn. Food-storage structures were built in places that were very difficult to reach. And, toward the end, windows between different parts of the cliff dwellings were blocked with rocks, dividing people.

Video: Mesa Verde Story (8:29)

PRESENTER: This is a wonderful, but a little bit disturbing, story of some really smart people living in southwestern Colorado, ancestral Puebloans, at a place called Mesa Verde. They lived there for hundreds of years and left shortly before Columbus got to the New World. A lot of their farming was done on top of a mesa, and they lived in caves down the side of the mesa in these wonderful structures made mostly out of stone. Here is a modern ladder with a person for scale.

And what I want you to notice here, in addition to the great buildings, is up here on top. This fairly clearly was a granary-- this is where they kept their food late in their existence there. It's probable, not certain, but it's probable that this is a little bit like a modern person putting the cookies way up on the upper shelf, so they won't eat them before they're ready to. Accept this wasn't the cookies, this was the food. And that might be something you'd do if food was really getting scarce.

Now that structure we just looked at, if you go behind it, you find it's actually built in a cave. And this is sandstone, and there's a little bits of shale and water sort of percolates down through here. And then it hits the shale, and it seeps out. So it's a little bit damp back there, in a generally dry climate.

And if you look around back here on this rock, do you see? You see things like this-- little holes they dug in the rock so that when water came seeping out, it would fall into these holes, drip in, and you could take a cup and get a little bit of water. And that's what you do if you're really thirsty because that doesn't look like the best water for us. But if that's all the water you have, that's what you do.

Now they built these wonderful structures, and some of them had windows between, say, your house and mine, or your room and mine. And late in the occupation, it appears that they walled the windows off. And usually, when you're walling the window off, you're trying to keep something out. And it is possible that they were not getting along with their neighbors quite as well as they might once have if they're walling off the windows within the structure.

Now if you go up on top where they grew the corn, this actually was built by the ancestral Puebloans, hundreds of years ago. And it stops erosion. So there's a little tiny stream comes through here, but this little dam of rocks catches a little bit of soil, where you could grow a little bit of corn. And it traps a little bit of water, and a little bit of soil. And so you're looking at people that really were shepherding what they had, conserving. And apparently, they needed this.

What you see then, is people who were living on the edge. Hard to get enough food, hard to get enough water, life was getting hard. If you look around the structure, it's mostly made of stone, because there weren't many trees. But there's a little bit of wood in the houses there at Mesa Verde.

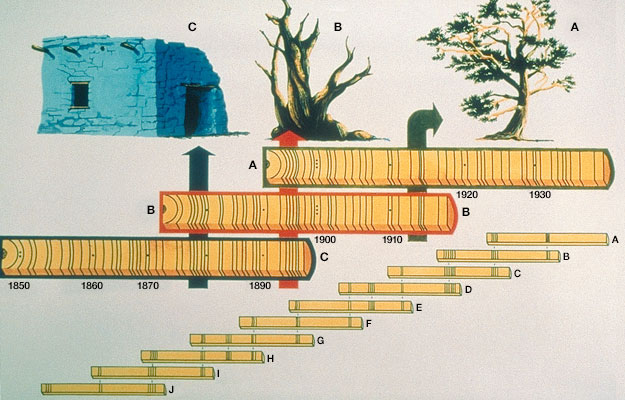

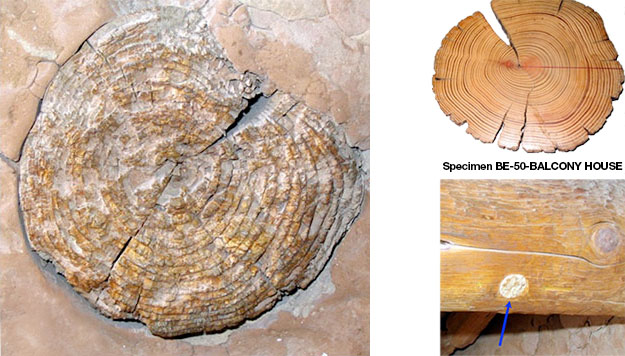

If you know anything about wood, you know that it has layers. And the layers, when the tree is happy, it grows a thick ring. And when the tree is unhappy, it grows a thinner ring. And you can see different thicknesses of rings in this.

And you can take cores, and you can count the layers, and count how thick the layers are. And in a place like Mesa Verde, where it's very dry, a happy tree is one that has rain. And an unhappy tree doesn't.

It's also possible, if you have a living tree, you can take a core from it, and you can see the pattern of thick and thin rings in that core. There might be dead trees nearby, and you can see the pattern of thick and thin rings in that, and you can match them up between trees. And you can go back to the wood in the archaeological sites, and you can find the same pattern. And so you can make a tree ring record, which is longer than the life of any given tree, with the thickness of the ring telling you how much it rained.

So now what can you do? Archaeologists and tree ring people got together. And they made the plot that you're going to see here. The year 800 is on your left, the year 1200, 1300 there, which is sort of the crash.

And so first of all, you have in green here, a history of how many people could live in the area. And this is actually done just down the road from Mesa Verde, at a place called Long House Valley that had less trade, so it was easier to work on. And what they did is they looked at the trees, and they said how thick a layer is, is how much it rained.

Rain also tells you how much corn could be grown, and corn is how many people could live there. So the green curve is from trees and from knowledge of the people-- how many people could live in this place. Independently, archaeologists went in and they looked at the classical things-- how many people were living there? You know, how many burials, and how many houses, and that sort of thing. And so they looked at how many people were living there, and that's this curve.

And what you'll notice is within the scientific uncertainties of all this, these are the same record. How many people lived there, and how many people could live there, are essentially the same. When it got wet, population went up. When it got dry, we don't know whether they died, or whether they left, or whether they quit having babies. But the population went down.

And the rains came back, and so did the people. And then the rains left. And at some point, the people said, we are out of here. We're going to become environmental refugees, and we're going to go someplace it rains more. And they left.

And so these are very smart people, doing amazing things. But they were controlled by the climate, ultimately. And it got them in the end.

Now, this is more recent. This is Oklahoma from the year 1900 to the year 2000. And the red curve here now is a history of drought.

And down is really dry, and this thing right down here is the Dust Bowl. And that made great literature, but it made lousy living, and you've probably seen the pictures of the Okies headed for California to get away from the dust. But look at the population history of Oklahoma, and you'll see that while the Dust Bowl kicked them-- and then World War II, some probably going off to war-- it's not nearly the disaster it was for the ancestral Puebloans.

Now, these are also smart people, but these are people that when the drought hit, some of them got in gasoline-powered cars and they drove away. But some of them had food delivered in gasoline-powered cars, or in diesel-powered trains. They had diesel-powered well drilling, that they could drill a well, and they could run motors, or run windmills to pump water out. And so they had more tools, and they had more stuff-- and those were fossil-fueled.

And more recently, when other droughts have occurred, it really hasn't affected the population much at all. Little tiny changes, but really not too much. And so what you can see is our having fossil fuels, and having machines, and having trade has greatly insulated us from what otherwise would be disasters for even very smart people.

Some of the evidence we saw at Mesa Verde of people dealing with hard times caused by a drought.

The evidence is very clear that the people were conserving water and soil, working to maintain and improve their ability to grow food. The hard-to-reach food storage might be a truly serious version of someone hiding something on the top shelf so they don’t eat it before they should, and the window-blocking is at least suggestive of increasing social stresses.

To learn more of this story, scientists went to Long House Valley in Arizona, a simpler place nearby that was occupied by the same people. Recall that the age of a tree can be learned by counting its yearly rings. These rings are easy to see in places where there are pronounced seasons because trees grow rapidly during the spring and early summer, putting on a lot of new wood that appears lighter in color, and then during the fall and winter, the growth slows way down and very little wood is added; this late-season wood is denser and darker. So, one thick light band and a thin darker band make up one year. This is sometimes not the case for trees that grow in the tropics, where there may be little difference between summer and winter, however, if tropical settings with defined wet and dry seasons, trees do develop annual rings. The important thing is that there needs to be a seasonality for trees to develop annual rings. In the dry climate of a place like Long House, trees grow better when it is wetter in the growing season, so a tree will thicker annual rings — the ring thickness is directly correlated to the amount of rainfall. In colder climates, the ring width can be correlated to temperatures during the growing season — warmer temperatures lead to thicker rings.

Thus, tree rings preserve a record of the climate history — rainfall in drier regions and temperature in colder regions. And, living trees overlap in age with trees that were used in construction, or trees that died but haven’t rotted yet. Using the pattern of thick and thin years to match the modern and older wood (a technique called cross-dating), the history of rainfall can be extended beyond the life of a single tree. Cross-dating has enabled us to produce continuous tree ring records that go back about 12,000 years even though the oldest living tree is just a bit over 5,000 years.