Central Valley/San Joaquin Valley Aquifer System

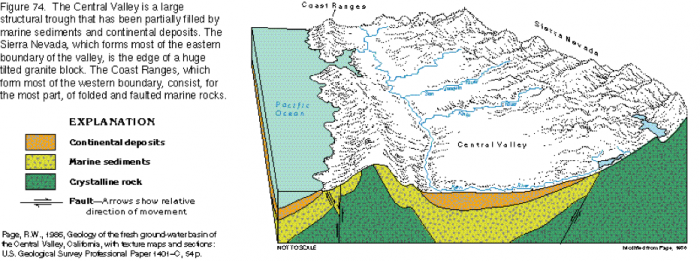

The Central Valley Aquifer system of Central CA lies in a large structural basin running approximately North-South, between the Coast Ranges to the West and the Sierra Nevada mountains to the East (Figure 22). The deep elongate basin is infilled with marine and continental sediments, primarily composed of interlayered sands and clays. The basin itself is formed by tectonic processes caused by East-West extension (these are the same forces that are causing continued uplift of the major mountain chains throughout the Basin and Range province of the Southwestern US, and which are one major control on orographic precipitation patterns in that region).

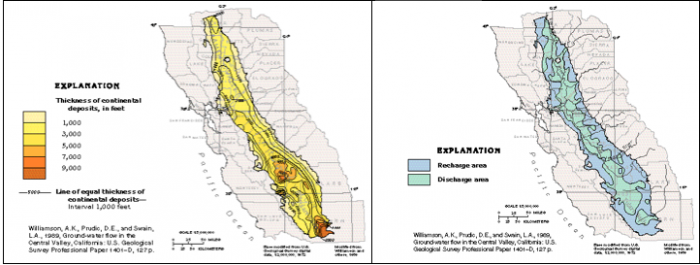

The continental deposits (Figure 22, orange) comprise the main aquifer units and range from one-half to over two miles in thickness. As is the case in the Valley and Ridge, the recharge is primarily focused around the valley perimeter as runoff over the flanks of surrounding high topography infiltrates and enters the groundwater system. Groundwater flow is primarily inward, toward valley center, with a component of flow down-valley to the North, parallel to surface water flow in the San Joaquin River.

The thick sedimentary sequence has formed a vast expanse of flat topography on the natural floodplain of the San Joaquin River. This, in combination with a mild climate that allows a year-round growing season, has made the Central Valley one of the most productive and largest agricultural centers in the world. The Central Valley aquifer system is highly utilized, primarily to augment limited allocations of surface water for irrigation. Since the mid-1920s, groundwater withdrawals have generally outpaced natural recharge to the aquifer, leading to dropping water levels, irreversible aquifer compaction, and land subsidence (as will be discussed in more detail next week, in Module 6.2). Until recently, groundwater withdrawals were neither heavily monitored nor regulated. However, in the face of an ongoing multi-year drought, a 2014 bill was signed into law that restricts pumping and implements groundwater sustainability plans (See What to Know about California's New Groundwater Law; see also New California Groundwater Pumping Rules Signed Into Law). Shallow aquifer units in the valley are also plagued by a wide range of water quality concerns associated with irrigation and return flow of irrigation water to the aquifer via infiltration; these include leaching of selenium, boron, and other constituents from soils; salinization; and high concentrations of pesticides and fertilizers. We’ll discuss all of these issues in more detail in upcoming modules about water quality and the effects of climate change.