Objectives

The objectives of a nonmarket strategy accomplish two things: they focus attention on the issue, and they help clarify alignment between stakeholders (those who are on the same side, who have the same or similar objectives). It is often helpful to specify a primary objective (stop this bill from getting passed!) but also a contingency objective (if it does pass, attempt to get, or avoid, some key wording). "For example, the domestic auto industry abandoned its primary objective of preventing higher fuel economy standards and adopted its contingent objective of obtaining flexibility in meeting the standards and measures to protect U.S. jobs" (Baron, 2010, p. 191).

Institutional Arena

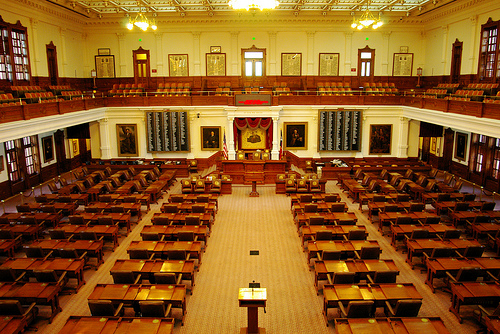

Government arenas exist at many levels, including local, state, federal, and international, and they may take many different forms, from legislative to judicial and all the oversight agencies in between. Often, stakeholders may have some say in the arena where the issue will be addressed. Determining the desired arena can be a significant step in the development of a nonmarket strategy for resolving an issue.

Usually, nonmarket issues are initiated by interest groups. For example, in the case of electric vehicles that are too quiet, the issue was raised by consumer complaints. And typically, the stakeholder(s) that initiate an issue are the ones that determine where the issue will be addressed. But this is not always the case. Sometimes other stakeholders, including firms, may have an opportunity to drive the selection of an institutional arena.

To Read Now

Carbon border taxes are an emerging issue in climate change policy. As more countries enact emissions limits, they may begin taxing certain imports to maintain fair competition. Please read the following article for some insight into this issue:

- "Europe Is Proposing a Border Carbon Tax. What Is It and How Will It Work?" New York Times, July of 2021. (Here is a link to a .pdf if you cannot access the article.)

Optional Reading

During the Trump Presidency, tariffs had become a major topic of discussion. Former President Trump repeatedly threatened tariffs on countries that manufacture goods outside of U.S. borders since early in his presidency, and enacted a number of controversial tariffs on a variety of goods. This is a very contentious issue, and is a prominent example of public politics.

- "Is Trump's Tariff Plan Constitutional?" by Rebecca M. Kysar in the New York Times (January 3, 2017) (Download the .pdf version here if necessary.) This provides some insight into some of the intricacies of U.S. tariff policy. This is an opinion piece, but note the different institutional arenas mentioned in the article.

- "President Trump's steel and aluminum tariffs raise two big questions." from CNN Money (March 9, 2018) for updates on this issue, and for details on an additional (international) arena, the World Trade Organization (WTO). Note that the WTO is not considered a public sector organization because it is intergovernmental and thus not run by a single governmental entity, and membership is voluntary. For the purposes of this course, it will be considered quasi-public and intergovernmental.

- Read this short article about the market impact that the steel tariffs have had on oil pipeline businesses in the U.S.: "U.S. shale shippers will pay surcharge for Trump steel tariffs" (Reuters, August 2nd, 2019)

- Read about some of the complexities involving energy infrastructure, farming, international trade, lobbying, and more related to the Trump Administration's tariffs: "Trump's Tariffs Set Off Storm of Lobbying" (New York Times, March 16th, 2018).

Nonmarket Strategy Approaches

There are three general approaches to nonmarket strategy in institutional (government) arenas: Representation, Majority Building, and Information Provision. Each type of strategy involves its own set of tactics, or activities, to execute the strategy.

- Representation Strategies are strategies that build on the connection between elected officials and their constituents. The elected official seeks to represent the “will” of the voters and wishes to be reelected. In this type of strategy, the stakeholder (a firm or interest group) takes action to mobilize voters in support of candidates that are favorable to the stakeholder. A firm may establish a presence in a region or district—for example, by building a facility contributing to the local economy and creating jobs or by forming an alliance with another stakeholder with constituents in the area.

- Majority Building Strategies are strategies that directly recruit the votes of public officeholders. This may be done through a variety of means, including vote trading between legislators (I’ll vote this way on A, if you’ll vote that way on B), stakeholder pledges of electoral support (voter mobilization and volunteers), other endorsements and advertisements, and campaign contributions.

- Informational Strategies are strategies that use advanced data, insights, or understandings that a firm or an interest group has about an issue. For example, a report that shows hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) for natural gas is costly to local municipalities may be used by fracking opponents to argue for a tax on fracking. The strategic use of information is a principal component in lobbying, legislative or regulatory proceedings, and public advocacy.

Please keep in mind that these are general approaches, not specific strategies. Strategies are explained on the next page.