Please read the following sentences, and think about the message(s) each one is giving you. Imagine that you don't know anything about the person who is making the statements other than what you read. Treat each example separately.

- I think solar panels are a wonderful technology, don't you?

- I have been in the energy business for almost 40 years, including 30 in the oil and gas industry. But like you, I'm a cost-conscious homeowner with bills to pay. I've never seen technology as potentially game-changing as solar panels. Those things are going to change the world, and better yet, they will save you money.

- Did you know that Tesla Energy will install and maintain solar panels on your roof for no extra cost? You don't have to lift a finger, and you will end up paying less for electricity than you do now. You can save money and get inexpensive, clean electricity. And all of it is guaranteed by contract! I had them install panels on my house, and couldn't be happier. They'll do the same for you.

- You know, every time I see that old coal-fired power plant I think of all of the innocent children living nearby that are probably having asthma attacks because of the pollution. That's why I added solar panels to my roof.

Each of these statements exhibits an attempt to convince you that solar panels are a good idea, but each in a different way. Think about the language devices employed in each of the sentences. What part of your psyche does it attempt to address? Is it logic, emotion, or something else? Are they obvious attempts to gain your agreement, or do they seem reasonable?

Rhetoric

Each of these sentences uses a different rhetorical strategy. Rhetorical strategies are the subject of this lesson, specifically the rhetorical triangle. At the root of all of this is rhetoric, so let's start there. This is just a quick video introduction - no need to take any notes or anything like that.

About 28 centuries ago, people really admired wisdom. They called it Sophos and people admired it so much they were willing to pay for it. They would hire Sophists to teach them all manner of things particularly law and politics, so the Sophists were traveling teachers and poets who roamed the countryside of Greece, and they taught anyone willing to pay to learn. As time went on, these Sophists became the most effective lawyers and gave advice to those governing the new Athenian democracy.

After a while, however, Socrates and his student Plato brought up the idea that the Sophists were not all that wise. In fact, they argued, what they were good at was structuring their lessons to simply sound wise. In essence, Socrates and Plato said the Sophists spoke so persuasively and so falsely that they could make listeners believe black was white. Also, Socrates and Plato objected to the fact that the Sophists charged for their services while they being both wise and noble dispensed their wisdom for free. They created such an uproar that even to this day the term Sophists is an insult. "You're a Sophist."

Not long after, Aristotle, a student of Plato, finally developed some rules for publicly dispensing wisdom and using language persuasively. He put down all his rules in a book, which he called The Art of Rhetoric. In The Art of Rhetoric, Aristotle separated out the wisdom from the skill needed to dispense it. He wrote down rules for arguing whence it required arguers to be ethical as well as persuasive. Aristotle laid out three appeals: logos, pathos, and ethos. He said the arguer should be logical, appeal to emotion, and build his trustworthiness with the audience by being ethical. He also listed 13 tricks or fallacies to avoid in arguing and laid out the ethics he thought an arguer should have.

Later, the Romans based their concepts on the Greeks. A Roman named Cicero came out with a text in the first century listing five canons of argument: (1) invention - creating ways to be persuasive; (2) arrangement - structuring an argument effectively; (3) style - presenting an argument so as to appeal to emotions; (4) memory - speaking extemporaneously; and (5) delivery - effective presentation. Cicero had so much to say that he put it into five books. When you understand that the Romans were very eager to practice law and politics, you understand why they cared about public speaking and argument enough to need five books.

Cicero's five canons influenced Europe for centuries. All students were taught grammar, logic, and rhetoric. After the Roman Empire fell, rhetoric existed only in the writing of letters and sermons. After a bit, people started preaching, and rhetoric became oral again. During the Renaissance, however, oral rhetoric became very popular once more (that's Shakespeare's time) far beyond preaching. The art of rhetoric became essential to lawyers, politicians, priests, and writers. Anyone who wished to persuade a wide audience sought to train in it, and this continues today.

Now, we've skipped over more than 1500 years of rhetoric and argument, but you have the basics. Today, unfortunately, the word rhetoric has taken on some of the negative connotations of sophistry. People think of it as eloquent speech designed to deceive, especially when politicians are involved. Calling something rhetoric is a pejorative.

And that is the history of argument in just over three minutes

Optional Viewing

Purdue University's Online Writing Lab (OWL) provides a lot of publicly available resources that are designed to help students and others become better writers. They do not allow embedded videos, so please click on the link below if you'd like to watch.

- "Introduction to Rhetoric." Purdue OWL.

Rhetoric/rhetorical arguments are designed to convince an audience of whatever the speaker is trying to say, or as Purdue OWL notes, it is "about using language in the most effective way." You most often hear this when referring to a politician, or at least someone acting politically or disingenuously, for example: "That speech was all rhetoric." When you hear or read this phrase, it is meant in a negative way and implies that the speaker was using language to trick the audience into believing the argument they were presenting. As noted in the video above, this negative connotation goes back centuries. But rhetoric has a few connotations, not all of them negative. It can refer to "the art of speaking or writing effectively," and "the study of writing or speaking as a means of communication or persuasion." These two definitions do not necessarily connote deceit. But it can also mean "insincere or grandiloquent language" (Credit: Merriam-Webster).

So, contrary to popular belief, rhetorical arguments are not always "insincere." That said, in this course, we are most concerned about seeing through rhetoric (rhetoric in the negative sense, that is) to evaluate arguments. Please note that rhetorical strategies can also be deployed visually - for example in images, photos, and video - and audibly. Advertisers do this all the time.

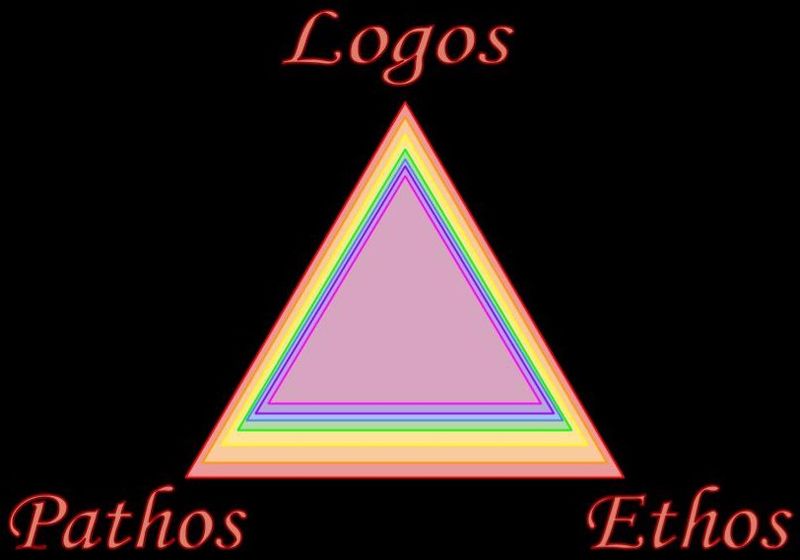

Ethos, Pathos, and Logos

Rhetoric is used to persuade people, and there are three general strategies used to do this: ethos, pathos, and logos. Please watch the video as an introduction to these strategies. We will then go into more detail in each in the following lessons.

Persuasion is an art. Great speakers throughout time have been able to change their listeners' minds and even move their audiences into action through the art of persuasion. Consider these persuasive speakers and how they changed the world through what they said.

For example, JFK in his speech where he said: "Ask not what your country can do for you but what you can do for your country." Or Ronald Reagan, twenty years ago when he said: "Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall," or Obama who inspired a nation to believe in hope instead of fear. Nelson Mandela, Gandhi, and even Oprah who persuades people every day to know better and to do better, or how about these leaders: Hitler, Stalin, Jim Jones, who brainwashed his congregation leaving 900 of them unknowingly to their deaths through a mass suicide order? Now, obviously, not all of these speakers are viewed as positive voices of change. These last examples even change the world for the worst, but let's face it: they did it through the art of persuasion.

Now, considering the fact that persuasion can be used for many purposes, it is important that individuals exercise ethical persuasive methods when seeking to persuade an audience. Let's face it: you could get an audience to believe anything you want them to if you have the right facts, a persuasive approach, and sometimes a willing audience. Some people accuse Obama of this, others accuse Rush Limbaugh of the same thing, but the fact remains that both of these men have been persuasive to certain people and groups by using information and motivational appeals. However, presenting facts on only one side of an issue without being transparent about the other side of the issue is sometimes unfair and unethical in seeking to persuade an audience. Think about it: I'm sure you've been on the receiving end of gossip: perhaps someone twisted a truth about you into something that wasn't true because they didn't share the whole truth or the full story. When people use information to make it say what they want it to say without sharing the other side, this can sometimes be considered unethical persuasion. It is important to use information and motive or motivational appeals ethically.

So let's talk about some specific motivational appeals summarized by the Greek philosopher Aristotle thousands of years ago. He believed that to be a truly effective speaker or writer, you had to appeal to three things when giving information to an audience or reader. The first is ethos or credibility. Ethos refers to the way in which a person convinces someone else to believe him or her simply by his or her character, credibility, and trustworthiness. We tend to believe and follow people we can respect. One can often increase ethos by being knowledgeable about your topic so that you have the authority and right to speak on the subject matter you are presenting. Another way to increase ethos is to appear thoughtful, fair, and respectful of alternative points of view. Your accuracy and thoughtfulness in crediting your sources, professionalism, and caring about your speech and its structure, your proper use of grammar, and your overall personal neatness are all part of the appeal to ethos.

The second motivational appeal described by Aristotle is pathos. Pathos refers to persuading by appealing to an audience's emotions, values, and beliefs. Word choice affects the audience's emotional response, and emotional appeals can effectively be used to enhance persuasion. This means that your speech should not only be someone else's words or research. You must tie together your research by crafting your speech with your own words in a way that is persuasive and interesting for your audience.

The third emotional appeal is logos. As you may assume from the term, logos is an appeal to reason or logic. This will be the most important technique you will use in your persuasive speech, and it was Aristotle's favorite. It includes the internal consistency and clarity of your speech. It requires that you make a claim and use quality reasons and evidence to support your claim. Just like a lawyer crafts his or her argument with a logical flow that appeals to the minds of the jury, so too must you put together a speech that has a logical flow of persuasion. Giving reason is the heart of persuasion and cannot be emphasized enough. You simply cannot and should not seek to persuade without strong information and a strong logical flow of that information.

Using ethos or credibility, pathos or emotional appeals, and logos or logic is important for any persuasive speaker. If you're seeking to truly persuade an audience, it's important to have all three: like one leg missing from a three-legged stool would cause the stool to collapse, so will your argument or persuasion collapse if you're missing one of these important motivational appeals. Remember, persuasion is not just standing in front of an audience and rattling off facts in hopes that your information will get an audience to change. The speaker must play an active role in persuasion. You are part of your persuasive message and your credibility, emotional appeals, and logic are important when preparing your speech.

So, good luck as you prepare to persuade. Changing minds, hearts, and actions isn't easy, but with the right attitude and preparation, you can succeed. Prepare for your own success and have fun while doing it.

Optional Reading

Purdue University has an excellent online writing lab. It has a lot of very helpful information, including how to use rhetorical strategies.

- "Ethos, Pathos, and Logos Definitions and Examples," PathosEthosLogos.com

- "Using Rhetorical Strategies for Persuasion," Purdue University Online Writing Lab

Good to Know

Ethos, pathos, and logos are rhetorical strategies, but these are not rhetorical devices. Rhetorical devices are specific methods that can be deployed to make a persuasive argument, whereas rhetorical strategies are general strategies. You have likely picked up on many of these devices when listening, reading, or speaking. Politicians are particularly fond of them. The "Mental Floss" website goes over some of them. If you Google around, you will find more.