“Urban segregation is not a frozen status quo, but rather a ceaseless social war in which the state intervenes regularly in the name of “progress,” “beautification” and even “social justice for the poor” to redraw spatial boundaries to the advantage of landowners, foreign investors, elite homeowners, and middle-class commuters” (Mike Davis, 2006, Planet of the Slums, p. 98)

Many of the ways that cities have been planned contribute to inequities such as educational quality and occupational opportunity. Well-known federal policies such as redlining and Jim Crow laws may no longer be legal, but the effects of these segregationist practices endure in cities today, impacting various dimensions of life including access to quality education, economic prospects, and good health. And while these overtly racist policies no longer exist, other less-obvious practices still contribute to differential access to resources, the built environment, and social opportunities within cities and their suburbs. As you read the following material, consider the cities you know and think about the different opportunities that residents might have based on where they live within those cities. Social inequalities in metropolitan areas stem from past as well as continuing practices that determine where and what types of roadways and transit opportunities are implemented or improved, assign specific uses (e.g. industrial, commercial, or single family or multi-family residential) to certain neighborhoods, and influence where parks and greenways get built or streetscapes maintained.

Jim Crow Laws & Residential Covenants

From the time of reconstruction after the U.S. Civil War until 1968, Jim Crow Laws in the Southern United States enforced racial segregation in places such as parks, public transit, and schools, among many other places. While Jim Crow laws were enacted in Southern states, residential covenants in other states kept people of color from moving into certain neighborhoods. For example, in Minneapolis one of the city’s first segregated residential areas stated that residences “shall not at any time be conveyed, mortgaged, or leased to any person or persons of Chinese, Japanese, Moorish, Turkish, Negro, Mongolian, or African blood or descent.”

Red Lining

Beginning in the 1930s, the U.S. government, through the Home Owners Loan Corp (HOLC), the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), and the Veterans Administration (VA), created color-coded maps for every metropolitan area in the United States. These maps divided cities into areas based on the risk of making loans and assigned colors for risk, with red being “hazardous.” Areas where African-Americans lived were systematically marked red and deemed too risky to insure for mortgages. Additionally, the FHA openly argued in their Underwriting Manual that racial groups should not be integrated, even stating that highways would serve as a good barrier for keeping white and Black communities separated.

Legacies of exclusion still persist from Jim Crow Laws, racially-based covenants, and redlining. These practices of the past continue to impact opportunities for people of color of today. Please watch this short, seven-minute video on housing segregation and some of the impacts past policies have on access to resources today.

Required video: Housing Segregation and Redlining in America: A Short History, NPR Code Switch (6:36 minutes)

Chris Rock, Comedian/Actor: You know what's so sad, man? You know what's wild? Martin Luther King stood for nonviolence. Now what's Martin Luther King? A street. And I don't give a f*** where you at in America, If you on Martin Luther King Boulevard there's some violence going down.

Gene, Narrator: That, of course, is Chris Rock’s famous joke about streets named for Martin Luther King Jr., which tend to be in -- let's say distressed areas. And he’s not wrong, because if you look at the way housing segregation works in America you can see how things ended up this way. Once you see it, you won't be able to unsee it. OK, let’s look at MLK Boulevard in Baltimore. I want to show you how to see housing segregation in schools, in health, in family wealth, in policing. But first, an explanatory comma.

It’s the 1930s in the wake of the Great Depression. FDR is president. He wants to bring economic relief to millions of Americans through a collection of federal programs and projects called The New Deal.

One part of that "new deal" was The National Housing Act of 1934, which introduced ideas like the 30-year mortgage and low, fixed interest rates. So now you have all these lower-income people who can afford homes, but how do you make sure they don't default on their new mortgages? Enter the Home Owners Loan Corp. The HOLC created residential security maps. And these maps? They're where the term redlining comes from. Green meant “best area, best people,” aka businessmen; blue meant “good people,” like white-collar families; yellow meant a “declining area,” with working class families; and red meant “detrimental influences, hazardous," like “foreign-born” people, “low-class whites," and -- most significantly -- “Negroes.” Again and again on these HOLC maps, one of the most consistent criteria for redlined neighborhoods is the presence of black and brown people.

Let’s be clear. Studies show that people who lived in redlined areas were not necessarily more likely to default on their mortgages. But redlining made it difficult — if not impossible — to buy or refinance. So landlords abandon their properties. City services become unreliable. In most places, crime increases. And property values drop. All of these conditions fester for 30 years as white people flee to the brand new suburbs popping up all over the country. Many of those suburbs institute rules, called covenants, that explicitly forbid selling homes to black people. And all of this was perfectly legal.

Now it’s 1968. And MLK is assassinated. News Report: Good evening. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, 39 years old, The apostle of nonviolence in the civil rights movement has been shot to death in Memphis, Tenn. Martin Luther King was shot and was killed tonight in Memphis, Tenn. In the aftermath, Congress passes the Fair Housing Act of 1968. It's a policy meant to encourage equal housing opportunities regardless of race, or religion or national origin. And it offers protections for future homeowners and renters, but does little to fix the damage already done.

Over the next 50 years, the Fair Housing Act is rarely enforced. So you can still see housing segregation and its effects, in Baltimore and often along any MLK Boulevard in any U.S. city. Like its effects on wealth. So homeownership is the major way Americans create wealth, right? Well, discrimination in housing is the major reason that black families up and down the income scale have a tiny fraction of the family wealth that white families do -- even white families with less education and lower incomes. For almost 30 years, 98 percent of FHA loans were handed out to white borrowers. Not only were black neighborhoods redlined, and not only was the Fair Housing Act selectively enforced, if at all, but it is still today much harder for a black person to get a mortgage or home loan than it is for a white person.

John P. Comer, Architects for Justice Advocate: Families are fearful of speaking up about a basic human right that should be afforded to everyone in the world but definitely in the richest country in the world. And housing segregation in schools. The primary way that Americans pay for public schools is by paying property taxes. People who live in more valuable homes have better-funded local schools, better-paid teachers, better school facilities and more resources.

Here’s a feedback loop: The better the schools in a neighborhood, the more those homes in that neighborhood are worth. And the higher the property values of those homes, the more money there is for schools. And so on and so on. And housing segregation in health. Because of urban planning that benefited those richer, whiter neighborhoods, people of color are more likely to live near industrial plants that spew toxic fumes; they're more likely to live far away from grocery stores with fresh food, and in places where the water isn’t drinkable. They're more likely to live in neighborhoods with crumbling infrastructure, and in homes with toxic paint.

Karen Holliday, Baltimore Resident: When you're living with rats, roaches, and things like that -- that's deplorable. You cannot have that kind of stuff with children running around in the building. A building that may be full of lead. And, not coincidentally, people of color have higher incidences of certain cancers, asthma and heart disease.

And housing segregation in policing.Housing segregation means we are having vastly different experiences with crime and vastly different experiences with policing. Because our neighborhoods are so segregated, sometimes racial profiling can be camouflaged as spatial profiling — where living in certain areas can make you more likely to be stopped by the police. And it means people have a lot of unnecessary contact with the criminal justice system just because of where they live.

Reggie Green, Baltimore Resident: The problem in our city? The police and the citizens are fighting. They keep targeting my brothers and sisters who don't really have nothing. And that heavy, aggressive kind of policing that you see in black neighborhoods in particular makes people feel like they can’t trust the police. And when people don’t trust the police, crimes go unsolved and people have to find other ways to keep themselves safe.

But, of course, it’s not just Baltimore. Because housing segregation and discrimination fundamentally shape the lives of people in nearly every major American city. It really is in everything. To hear more about how race shapes American life, visit npr.org/codeswitch. I'm Gene Demby. Be easy.

Urban Design, Development, & Exclusion

Redlining, racially-based covenants, and Jim Crow laws may no longer be legal means of segregation, however, less obvious strategies of exclusion persist in urban and suburban environments today. The design of cities and the built environment determines how residents can use and benefit from the city. Some factors that contribute to who lives where include the presence of sidewalks, access to public transportation, or even residential restrictions allowing only single-family homes to be built in certain areas. These less obvious forms of segregation impact who can access certain places based on car ownership or economic factors. Highways are also a tool used as a physical barrier separating neighborhoods by race or class. Using urban design and the built environment as tools to regulate public behavior and activities are not limited to the United States.

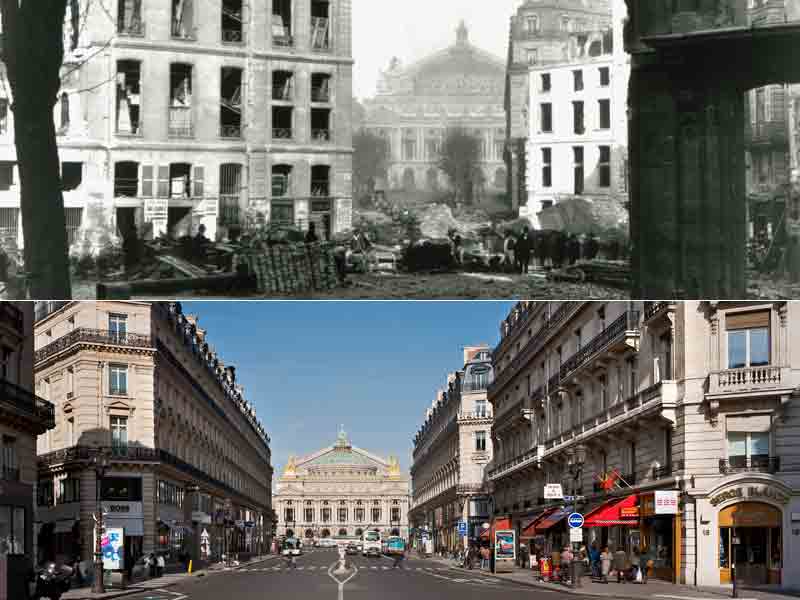

Haussmann’s Paris

In the 1850s, Emperor Napoleon III hired Georges-Eugène Haussmann to build grand boulevards through Paris’ most densely populated neighborhoods. In an effort to eradicate squalor and improve the health and appearance of Paris, Haussmann widened many of Paris’ streets and created a uniform design for the exterior of buildings. Today we think of these large, grand streets and the unique architecture of the center of Paris as emblematic of the city, but Haussmann also argued that his strategies prevented civil unrest and armed uprisings in Paris’ dark, crowded center-city. The wide streets would enable the military to easily navigate through the city, preventing Paris’ tightly built quarters from easily erecting barricades and serving as fortifications in uprisings. There may have been a military argument to these design changes, but the main effects of Paris’ widened streets decreased population density, increased rents, and forced low-income residents to relocate to outer suburbs.

Moses’ New York

Just as Haussmann shaped contemporary Paris, Robert Moses is credited with shaping New York City’s built environment. One of Moses’ greatest critics, the historian Lewis Mumford, wrote, “In the twentieth century, the influence of Robert Moses on the cities of America was greater than that of any other person.” Moses pushed through the building of almost 500 miles of urban highways, including the Triborough Bridge. He also built parks and playgrounds and developed beaches such as Jones Beach State Park for public use. His vision for an automobile-oriented city influenced cities across the country, ushering in a mode of urban planning focused on automobile use. Similar to Haussmann, Moses’ vision of a city had little sympathy for poorer residents and people of color. He used strategies such as building bridges too low to allow for public transit buses, thus limiting the access of poorer residents to places such as the newly developed public beaches. Often poorer residents were forced to relocate for the building of urban highways.

For an extensive history of Robert Moses’s impact on New York, and politics in general, read Robert Caro’s biography The Power Broker, which is available through the Penn State Libraries.

Environmental Impact

Systemic racism and classism also have implications for biodiversity and the ecological health of cities. Read this passage from the University of Washington discussing a review paper written by scientists from three universities:

“For example, several studies the authors included found fewer trees in low-income and racially minoritized neighborhoods in major cities across the U.S. Less tree cover means hotter temperatures and fewer plant and animal species. Additionally, these areas tend to be closer to industrial waste or dumping sites than wealthier, predominantly white areas — a reality that was put in place intentionally through policies like redlining, the authors explain.

Fewer trees, over decades, has led to pockets of neighborhoods that are hotter, more polluted, and have more disease-carrying pests such as rodents and mosquitoes that can survive in harsh environments. These ecological differences inevitably affect human health and well-being, the authors said.”

You can read the full review paper here: https://science.sciencemag.org/content/369/6510/eaay4497