So far, we’ve considered the ways that identities are relational and complex. We have determined that people identify in multiple ways simultaneously, that the process of identification creates relationships (in the most basic sense of the word) of inclusion and exclusion, and that our emotional engagement with identity may vary. Now we turn our attention to what it means for something (and in particular, for identity) to be socially constructed.

Social construction

As discussed in the Dictionary of Human Geography, social construction can be briefly defined thus:

The idea that the social context of individuals and groups constructs the reality that they know, rather than an independent material world. Knowledge is always relative to the social setting of the inquirers, the outcome of an ongoing, dynamic process of fabrication. (Gregory et al. 2009, p. 690).

In other words, to say that things are socially constructed is to say that they “are real if people think they are” (Jenkins, 2008, p. 45). On first glance, this is an unsettling idea; students are quick to argue that it suggests that all of reality is based only on people’s opinions, and thus it follows that everyone is right about everything and there is no objective reality. This response, common as it is, is a misunderstanding of what social construction means.

To say that something is socially constructed is to say that the forces or structures within our environment — the social and cultural context in which we live — have identified it as something meaningful or worthy of note, and that there is broad enough social and cultural consensus about the thing that people accept the thing as real, and have agreed on what that thing means, and how to perceive, discuss, or engage with that thing. A couple of examples will help illustrate what we mean here.

First, consider money. No one would dispute that the $5 bill one might use to buy a cup of coffee exists. Yet there is nothing inherently valuable about a $5 bill. We generally agree that we can exchange it for goods or services, but objectively speaking, it is nothing more than a piece of paper with some symbols on it, and while we can use it freely within the United States, no one outside the US is required to accept it as legal tender (though we might exchange it for euros, yen, pesos, lira, etc., depending on where we are). One might argue that it is inherently valuable because the US government says it is — but here’s the catch: there’s nothing inherently valuable in it if our entire ability to use it is predicated on some human collective’s decision that it’s valuable. The fact that the power of a $5 bill to buy things fluctuates over time as prices increase or decrease is an indicator that there is nothing objective about its value. That value — and, indeed, the concept of money itself — is socially constructed.

Second, consider the Olympic Games. The games exist only because a group of people decided to hold them, yet there is no single, canonical list of sports that belong in the Olympics, nor is there a single location where they take place, nor is there a natural ordering of events within the Olympics; these are all decided by the International Olympic Committee. While no one would dispute the prestige that countries take when their athletes medal in Olympic events, that prestige exists only because people collectively agree that medaling is a desirable and prestigious thing. The Olympics as an event, the games that take place during the Olympics, and the social, cultural, and political capital associated with winning — all of these are socially constructed.

To reiterate: no one taking a social constructionist view would argue that money or the Olympics are fictional or nonexistent. On the contrary, they would agree that these things are very real, and that they have real uses, meanings, or consequences for people (and nations). Likewise, a social constructionist would not hesitate to agree that features on the landscape (e.g., rivers, mountains, etc.) are real — but that person would remind us that the thresholds that determine which bodies of water are rivers (as opposed to creeks or streams) and what constitutes a mountain (as opposed to a hill) are somewhat arbitrary and socially constructed.

Identity, social construction, and discourse

Just as money, the Olympics, and features on the landscape are socially constructed, so are identities. Both the broad categories that we use (e.g., age, religion, race) are socially constructed, as are the relative positions within those categories (e.g., Black, White, Asian, Middle Eastern, etc.). To illustrate how these are socially constructed, consider, for example, how we determine what constitutes religion as opposed to myth or philosophy. Or, as in the exercise below, consider how we think about race.

Exercise 3:

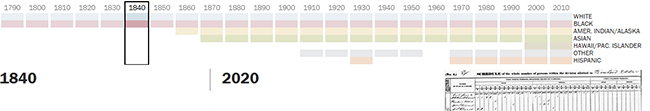

Use the following link (or click on the image below) to examine this interactive timeline from the Pew Research Center.

On it, you can trace the racial identities included in the decennial census since 1790. Compare the various racial designations that appeared on the census in the past to those on the 2020 census. How have these racial designations changed? Which designations have been consistent, and how consistent have they been? There are some that are no longer used today; do you recognize these as racial categories?

What this tells us about social constructs is that, while they are meaningful and consequential, they are not natural, but are instead contingent on some external factors. You might be wondering who determines, for example, what constitutes a social category that’s worthy of recognizing? And who determines, again, which positionalities exist within that category?

There are a number of forces and agents that create structure and define various constructs within society and what they mean for us. These guide the construction of some of the most pervasive and fundamental social constructs in society. We trace this idea to Michael Foucault, a French philosopher and historian who developed a theory of discourse. Writing from structuralist and post-structuralist traditions, Foucault’s major works — including Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity In the Age of Reason (originally published in 1961), Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (originally published in 1975), and The History of Sexuality (originally published in five volumes between 1976 and 1984) — laid out a historically-grounded explanation for the ways that institutions such as government, law, medicine, and education use their power to create and shape social constructs through the strategic use of language and terminology.

For example, in Madness and Civilization, Foucault follows the historical treatment of people who were constructed as ‘mad’ or ‘insane’ by European societies, noting they were regarded as a source of wisdom during the Renaissance, as morally-corrupt outcasts in need of confinement during the Enlightenment, and as sick people who might be cured during the Modern era. The changing social construction of mental illness, he argues, was brought about by institutional shifts that entailed new terminologies, institutional attitudes, legal constructions, and social beliefs about mental health (see Foucault, 1995). In fact, my very use of the terms ‘mental health’ and ‘mental illness’ reflect what Foucault might describe as our contemporary discourses of ‘madness’: discourses that codify diagnoses of ‘mental disorders’ in documents like the ICD-10 and the DSM-V, and that entail treatment such as medications, therapy, or short-term hospitalization (as opposed to earlier discourses that might have revolved, instead, around the marginalization and imprisonment of people with mental health issues).

Just as identities are socially constructed through a critical mass of everyday activity that creates new positionalities through activism and visibility via popular culture and social media, identities are also discursively constructed. We have seen this already in the example of racial designations in the US Census. The Census Bureau, as an arm of the government, has the ability to determine which positionalities count as legitimate through its use of language and terminology. As we see in the readings by Krogstad (2014) and Wang (2018), discussion about whether to include Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) as a racial category in the census provides an excellent example of discursive processes that have taken place within the last decade.

It is crucial to recognize here that both social and discursive constructions of phenomena (especially identity positions) vary from culture to culture. This is in large measure due to differences in things like migration histories, the presence of different minority populations, and institutional policies that determine which groups of people should be recognized for protection or persecution. That is, social constructions (and discursive constructions) are rarely universal. Even if the same designations exist in two different cultures, the policies, beliefs, and expectations surrounding those designations may vary drastically.

Normalization

As a final note about both the social and discursive constructions of identities, it is important to be aware that some identity designations or positions become normalized through the processes of construction. That is, certain designations take on the connotation of being ‘normal’ and are assumed to be the standard, neutral, or ‘unmarked’ (see Tannen, 1993 and Brekhus, 1998) positions — and because of this, these positions are sometimes left as undefined or are presumed to be self-evident, and thus unworthy of inquiry. These positions are typically dominant within a particular culture; those positions that are considered different or other are given new terms.

We can see a clear example of this at work in the US Census Bureau’s racial designations that you explored in the exercise above. Notice that the designation ‘White’ barely changes throughout the entire history of the census. In the earliest years, the designation is “Free white males and free white females,” which changes to “White” for the 1850 census and remains unchanged from that point forward. Contrast this with the very visible and more rapidly changing racial designators for everyone else. This is an indicator (along with its status at the top of the list) that “White” is the dominant, unmarked racial designator.

It is important to bear in mind that normalized identities still qualify as identities, even if they are dominant. They may be less obvious because of their dominance, but this does not make them any less effective or important an identity than any other designation.

Read:

Krogstad, J. M. (2014, March 24). Census Bureau explores new Middle East/North Africa ethnic category. Pew Research Center.

Wang, H. L. (2018, January 29). No Middle Eastern or North African category on 2020 census, bureau says. NPR.

Recommended:

Foucault, M. (1995). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Vintage Books.

Additional References:

Brekhus, W. (1998). A Sociology of the unmarked: Redirecting our focus. Sociological Theory, 16(1), 34-51.

Foucault, M. (1995). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Vintage Books.

Foucault, M. (1973). Madness and civilization: A history of insanity in the age of reason. Vintage Books.

Gregory, D., Johnston, R., Pratt, G., Watts, M. J., and Whatmore, S. (Eds.). (2009). The dictionary of human geography. Wiley-Blackwell.

Jenkins, R. (2008). Social identity. London: Routledge.

Tannen, D. (1993, June 20). There is no unmarked woman. The New York Times Magazine.