Differences Between Writing an Academic Paper and a Brief

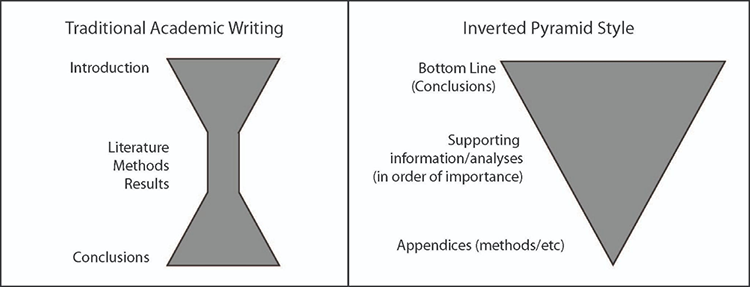

Throughout your academic life, you’ve been told to start with a broad concept and work your way to more specificity about your research and topic. You’re expected to write eloquently, sometimes for many pages at a time. The traditional academic paper is written more like an hourglass: you introduce your topic and hypothesis, provide an overview of relevant literature, discuss your methods, then get to your results, and finally your conclusions and implications. A reader must read all the way to the bottom in order to gain your insights and conclusions.

When writing a brief, you want to forget that construct. Remove it from your brain. Do the opposite.

I know, easier said than done.

The purpose of a written brief is to be…well…brief. You need to be able to convey the most important information to your customer as quickly, concisely, and clearly as possible. The key here is knowing who your customer is, what they need to know to do their job, and putting your bottom line up front. Many refer to this style of writing as the “inverted pyramid,” where your conclusions are actually the first sentence of your paragraph (Brown, 2020) (Figure 3.1). This can be difficult for academically trained analysts to wrap their minds around.

© Penn State University is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Important Aspects of a Written Brief:

According to the Analyst's Style Manual (Welch, 2008), there are six rules to intelligence writing:

- Put your bottom line, main message, or most important conclusion first

- Write short paragraphs

- Use the active voice

- Avoid verbose language

- Write short sentences

- Pay attention to your credibility:

- Spelling and grammar are important to building your credibility.

- Make sure your arguments are based in fact and logic.

- Use citations.

Elements of a Successful Brief

© Penn State University is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

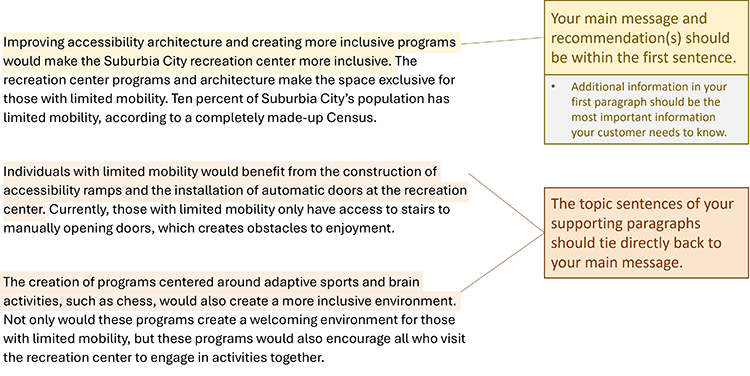

Improving accessibility architecture and creating more inclusive programs would make the Suburbia City recreation center more inclusive. The recreation center programs and architecture make the space exclusive for those with limited mobility. Ten percent of Suburbia City’s population has limited mobility, according to a completely made-up Census.

- Your main message and recommendation(s) should be within the first sentence.

- Additional information in your first paragraph should be the most important information your customer needs to know.

Individuals with limited mobility would benefit from the construction of accessibility ramps and the installation of automatic doors at the recreation center. Currently, those with limited mobility only have access to stairs to manually opening doors, which creates obstacles to enjoyment.

The creation of programs centered around adaptive sports and brain activities, such as chess, would also create a more inclusive environment. Not only would these programs create a welcoming environment for those with limited mobility, but these programs would also encourage all who visit the recreation center to engage in activities together.

- The topic sentences of your supporting paragraphs should tie directly back to your main message.

References

Brown, Z. T. (2020, July 16). How you can write like an intelligence analyst. Zachery Tyson Brown.

Welch, B. (2008). The Analyst’s Style Manual. Mercyhurst College Institute for Intelligence Studies Press.