The Human Factor

Team Dynamics and Managing Teams

Just because a project manager has used all of the tools, discussed in previous section, to manage human resources in the most efficient manner possible, it is no guarantee that the project team will be effective. To be effective, a manager should understand how a team works together, what motivates people, have a detailed understanding of team memer skills and limitations, and develop management skills to efficiently delegate and oversee work.

Much has been made of teamwork and building effective teams. Synergy is a popular concept; it means that the efforts of the team are superior to the sum of what all of the individual efforts would have been. Achieving such a lofty goal is only possible if project team members have a good understanding of themselves, their teammates, and the methods by which they tend to work together.

Team-building activities can be physical in nature and may only be possible to achieve when multiple members of a team work together to achieve a goal, underscoring the very definition of synergy. Unfortunately, we won't be able to build teams this way in this class. What we will be able to do is to attempt to increase our understanding of ourselves and other members of the class.

Tests to gauge personality types and employee motivational factors are sometimes used to help understand work styles, motivational factors, personality characteristics that impact project team member interactions provide a basis for assignment of project roles and task assignments. Two of the most popular of these are the Meyers-Briggs Type Indicator and the Social Styles Profile. Meyers-Briggs includes four dimensions of personality, meaning that everyone falls somewhere between the two logical ends of each dimension. The first dimension indicates where people fall on the scale between introverts or extroverts. The second dimension ranges from sensation to intuition, reflecting the way one takes in and process information. The third dimension goes from thinking to feeling, and measures how objectively or subjectively a person tends to judge people or things. The final dimension moves from judgment to perception, and is meant to reflect attitudes towards structures and plans."

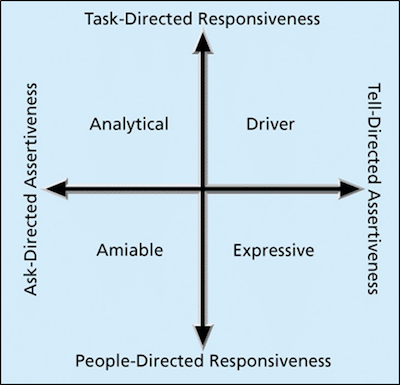

The Social Styles Profile defines four zones, with the assumption that most people operate primarily in one of these zones. The zones are based on assertiveness and responsiveness. In this scheme, people are drivers (proactive and task-oriented), expressives (proactive and people-oriented), analyticals (reactive and task-oriented), or amiables (reactive and people-oriented). A GIS project manager may be a driver, but should appreciate and be able to work effectively with the team's analytical GIS Analyst, amiable GIS Technician, and expressive end user. Figure 4-4 below, diagrams how these social styles can be mapped.

Click for text description of Figure 4-4: Social Style Profile

This figure explains the concept of a person's social profile. It has two gold double-arrow lines that meet in the center and form 4 quadrants labeled Analytical (upper left), Driver (upper right), Amiable (lower left), and Expressive (lower right). The vertical arrow points to a label at the top called Task-Directed Responsiveness (referring to the top two quadrants). The vertical arrow points to a label at the bottom called People-Directed Responsiveness (referring to the bottom two quadrants). The horizontal arrow points to a label at the left called Ask-Directed Assertiveness (referring to the left two quadrants). The horizontal arrow points to a label at the right called Tell-Directed Responsiveness (referring to the right two quadrants).

Formal testing takes time and often money if an outside service is contracted to administer the tests and process the results. For this reason, it is not frequently used as part of project team member selection. But, in large projects, formal testing should be considered. It can help an organization assemble the right mix of people and provide insights to the project manager for work delegation and team management.

Another useful testing method, designed to gauge key factors that motivate people for certain types of job assignments, is the Kolbe A Index. The Kolbe Corporation states that this test "measures the conative faculty of the mind — the actions you take that result from your natural instincts, and is the foundational instrument used in Kolbe reports. It validates an individual's natural talents, the instinctive method of operation (M.O.) that enables you to be productive.

You may be wondering if there is a particular personality or motivational type that makes one best suited to be a project manager. The answer is an emphatic "NO". A successful project manager leverages his or her attributes and personal approach in project planning and execution. Project managers do need to be organized, acquire management skills, and become familiar with methodologies that work in a range of project scenarios. A natural introvert may need to learn and apply some communication skills of an extrovert, and the reverse is also true. But most of the key skills and methods of a successful project manager are learned—through appropriate training and application in real-world environments.

An important part of the project manager's job is organizing the work for team members and ensuring that team members are maintaining a high level of productivity—always with a focus on the project objectives. As discussed in Croswell (2022), subsections 4.1.7 and 4.1.8, effective team management has a lot to do with work delegation and maintaining team member morale. In summary, the following best practices make practical sense and should be applied in all GIS projects:

- Be open to communication from staff members. Take their concerns seriously, listen, and take appropriate action

- Be clear in work assignments and provide the resources employees need to do their jobs

- To the extent possible, make adjustments to the physical work environment (furniture, workstation location or layout, supplies) to increase efficiency or to simply address employees’ esthetic or personal needs

- Be prompt and clear when conveying information. Even when it is necessary to explain bad news or changes, it is best to be upfront and present a constructive way to deal with it

- Don’t micromanage. When employees have the necessary skills for a job, a manager should clearly define objectives, help in the planning and defining scope specifications, provide resources necessary for the work, put in place a sensible process for status review, and be available for support and clarification. But, assigned project team members should be encouraged to move ahead with the work without unnecessary oversight

- Be fair and don’t show personal favoritism

- Be sensitive to staff members’ personal situations and the “work-life balance” that might affect work. To the extent possible, provide support and be flexible when scheduling work and leave. Make use of the organization’s employee assistance programs if they are available

- Establish realistic milestones with points for review of performance

- Find ways to give regular feedback to employees and to offer performance incentives and rewards when performance justifies it