Greenhouse Emissions and Carbon Taxes

The Most Contentious Facet of Sustainability

I'd like us all to temporarily cleanse our minds of any preconceived notions of greenhouse gases or carbon. Deep breath in, hold for 5 counts, deep breath out. Go to a serene place. Get a beverage and come back. I'll wait.

There are entire swaths of the practice of sustainability which, with discussion, rationale, and logic, can be met with incredible support in virtually every corner. Waste minimization and energy reduction tend to fall into this category. It's about living lean, reducing waste, and saving money while saving the planet. It's about responsibility, stewardship, and not wasting all of the work it took to create that aluminum can. It takes a little messaging and discussion, but, invariably, success can be had with even the most skeptical among us.

And then comes the issue of greenhouse gases (GHG) and carbon taxes.

In this topic, I would like us to explore a concept known as The Tragedy of the Commons (Hardin, 1968) as an entry point to help us understand why carbon regulation is a logical step which can help drive innovation and eliminate the market-biasing subsidies mentioned in the last section. For more about this please watch the following 6:36 video.

Video: Tragedy of the commons | Consumer and producer surplus | Microeconomics (6:36)

Let's say that we have three small ponds. This is pond A, this is pond B and this is pond C over here. Let's say that this first pond right over here, it's a privately owned pond. It's owned by Al and this pond over here is owned by Carol.

But this middle pond, pond B I guess we called it to start off with. This is common land, or I guess this is a common pond or this is open to the public.

Let's say that Al and Carol, they're both fishers. I guess Carol would be a fisherwoman. They both like to fish, that's how they make their living. Al in his pond, he has fish in there and he does some fishing in his pond. But he makes sure not to overfish because he doesn't want to deplete the stock of fish he has. He fishes just enough that he can pay his bills and whatever else but not so much that it depletes the fish and essentially makes them extinct in his pond. He doesn't want to overfish, and Carol does the same thing. She's got fish in her pond and she uses them to make a living. She gets them out and sells them and eats them and whatever else but she's careful not to overfish because if you overfish then there wouldn't be fish. There wouldn't be a next generation of fish.

Over here in this public pond, there are also fish. I'll draw their fish in orange. There are also fish in this public pond over here. They're smiling, maybe they won't be smiling for long. What is going to happen? Anyone can go and fish in this public pond. Al might say, and we'll just assume we’re in a world of two people. Obviously, the real world has more than two people.

Al will say, "Okay. I'm going to be very careful in my own pond. I'm going to fish just enough that I don't deplete the fish there. But any extra fish I need, I could go over here to this public pond and fish all I want." And I might be concerned about depletion in the public pond except for the fact, if I'm concerned about depletion, that's still not going to help the situation because other people might come and still not be so concerned and so I won't even get the benefit of the depletion if I hold back and other people come and deplete the pond.

When you have this pond that is open to the public, all of the surrounding people whether it's Al or Carol or I guess you could have other people here, they would say, "Look. I'm going to fish here. I'm going to get some benefit and even if I overfish the benefit of overfishing I'm going to get. In the near term I'm going to get all of those fish." Then the cost of that overfishing which is in the future there won't be as many fish or no fish at all, that's going to be spread out amongst everyone else.

So you have the situation where, because there's no one, I guess you could say, either owning this land or there's no one protecting this lake or however you want to describe it, there's a rational. And I want to be clear, rational does not always mean good. Rational actors might decide to overfish.

Essentially, by doing that, everyone's going to be worse off. They're going to destroy the productivity of this pond. They're going to destroy the productivity of the pond right over here. This idea that if there's this common land or common resource, in this case it was a pond and people can spread out the cause and they get the benefits directly. Essentially, you have a situation where that shared resource can get abused and this is called the tragedy of the commons.

This is the tragedy of the commons where in the example we did here, the pond is the common space that's being abused. It's especially a tragedy and I've already hinted at this already, is that even if Al decides that, "Hey, you know what? I'm going to hold back a little bit. I'm not going to fish so much because I don't want to deplete it." He'll say, "But wait. If do that, other people are going to come and deplete it so I have no incentive to hold back." So other people are also going to have the same logic and then this thing is going to get overfished here.

The classic example of tragedy of the commons where the example was first given was common grazing lands. Same exact idea. If this was private grazing land over here where I can keep my cows and my sheep and this is private grazing land over here where someone else has their cow and sheep but this over here is literally a commons where anyone can graze their cow and sheep. Then, just like the fishing, huge incentive for people to let their cow and sheep maybe overgraze the land, destroy the land, make it not sustainable but the cost of it are going to be shared by everyone else and the benefit of overgrazing, at least in the near term, you, the person who's overgrazing is going to get from it. You might even say, "I'm not even the one overgrazing it. It's all of us collectively overgrazing." So you don't blame me.

Now, what is the solution to the tragedy of the commons? How does a government or jurisdiction or a group of people avoid this type of destruction of a resource?

Well, one way that you could do is you could make this somehow into private land. If that was owned by the government, it could sell it, auction it off to private people who could then sell access to this. Or if the government does retain control of it, it could sell permits to the land. In this situation, you could sell permits. I could figure out hey, if someone fishes responsibly in a given day, they're going to get, I don't know, $200 of value by doing this. We're going to make a permit cost, I don't know, $150 so that someone still has an incentive to do it but that will also limit the amount of fishing that can be there and we can have some conservationist that makes sure that not too many permits are given for this space over here. We see that happening.

If you wanted to go hunting, there are permits you need to have. If you want to go fishing in a lot of places, there are permits that you want to have. If you want to go camping in a lot of places, there are permits because you could even over-camp an area if too many people are walking there, too much trash is there. It could ruin the camp grounds.

So this tragedy of the commons, the best way or the way most often seen, the best way of preventing the tragedy of the commons is through some type of a permitting process.

If you would like, you can read Hardin's original 1968 article setting forth this concept.

The Tragedy of the Commons is an intuitive explanation of something that happens every day in the world around us: finite, common-access resources–such as air, water, or fisheries–are depleted when individuals are given unrestricted access. In this regard, we must remember that the concept of "maximizing gain" is not necessarily restricted to physical benefit, but to any erosion of public resources by the self-interests of individuals. Regardless of the specific expression of the Tragedy of the Commons, the ultimate result is the same: the resource is either depleted or eroded to the point of collapse.

Greenhouse gases could perhaps be the purest expression of The Tragedy of the Commons: a byproduct which is invisible and created in thousands of ways in daily life and that will damage entire systems of common resources, worldwide. The idea of a finite, tangible resource, such as a pasture or pond being depleted is quite accessible, but when it comes to impacts on the scale of greenhouse gases, it can be so large as to be almost inconceivable.

Greenhouse Gases

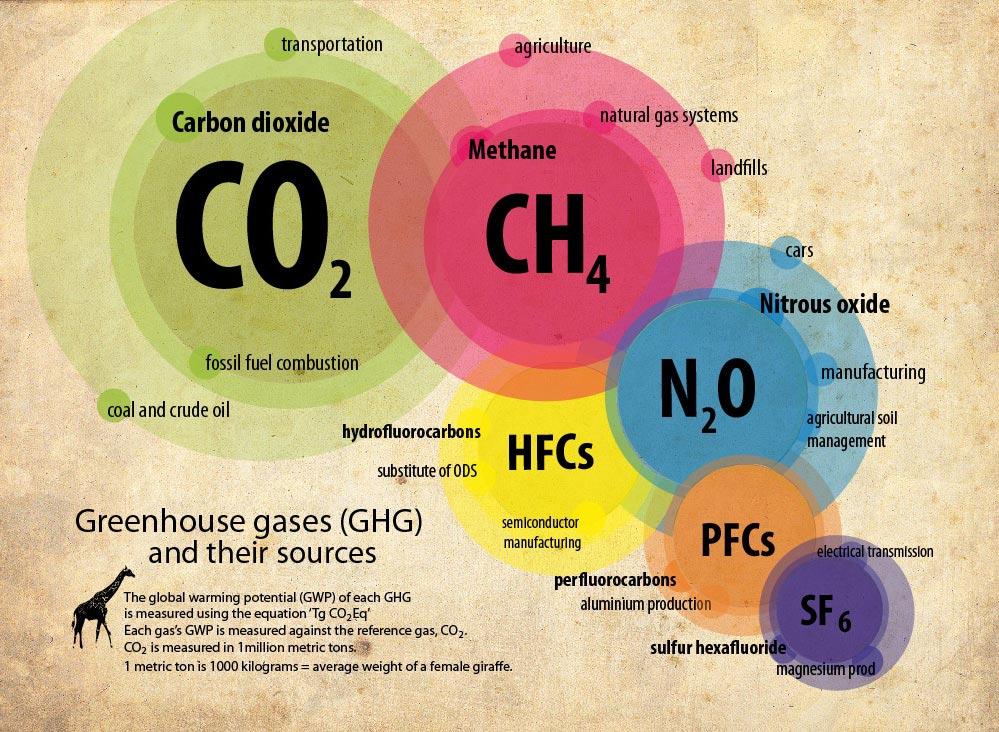

Greenhouse gases refer to a group of seven gases found in the atmosphere: carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs), and sulfur hexafluoride. There is also some level of discussion about other potential greenhouse gases, one of which is perfluorotributylamine, a man-made chemical which currently exists in extremely small quantities in the atmosphere, yet is "7.100 times more powerful at warming the Earth over a 100-year time span than CO2" (Goldenburg, 2013). Typically, the discussion on greenhouse gases tends to center squarely on carbon dioxide, as it is the most prevalent greenhouse gas and is generated heavily through the combustion of fossil fuels. In total, greenhouse gases share a common attribute in that they trap heat (infrared radiation) in the atmosphere and work to elevate temperatures.

In sustainability reporting and in the calculation of the greenhouse gases generated from an entity (commonly referred to as the "carbon footprint"), the common measure used is carbon dioxide equivalent or "CO2e", which accounts for the emission of carbon dioxide and methane. The amount of these gases generated is typically normalized as "kilograms of CO2e" per (hour, mile, kilowatt or other measure of usage or operation) and can be utilized in measuring the emissions of virtually any direct or indirect activity, from operating a tractor to composting. Measuring and reporting carbon emissions is made easier by the excellent availability of data to calculate Scope 1 (direct) carbon emissions, but measurement becomes far more complicated in the calculation of Scope 2 and Scope 3 (indirect) emissions. These emissions are generated in the creation of energy utilized (Scope 2) or as consequences of transport, production, supply chain, and other outside activities (Scope 3). As we will see in many issues of sustainability in coming lessons, measuring and reporting Scope 2 or 3 emissions many times requires one to make estimations and judgment calls based on the best information available... and many times, comes down to being transparent about the assumptions made.

If you would like to see an example of Scope 1, 2, and 3 carbon emissions created in the brewing of beer, take a look at New Belgium Brewing Company's graphic representation of their GHG emissions.

In general, NBB, Sierra Nevada, and Full Sail Brewing Co. have some rather innovative approaches to sustainability, measurement and messaging.

Carbon Taxes

We may consider that any currency, be it the US Dollar or any other, is not inherently "good" or "bad". It is simply a mechanism by which the market accepts and unifies around a means of trade. We may consider the sheer mechanism of CO2e measurement in a similar way. It is a mechanism which the world at large accepts as the unified measurement of greenhouse emissions from virtually any activity from lighting a baseball field to burning off a wheat field. CO2e is so able to be empirically measured, we can even go as far as discerning the difference in emissions from burning the wheat straw residue vs rice straw residue:

| Biomass type | CH4 | CO2 | CO | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emission factor (g/kg) | ||||

| Agricultural residue | 2.70 | 1515±177 | 92±84 | 44 |

| Wheat straw | 7.37± 2.72 | 156±22 | 45 | |

| Rice straw | 5.32±3.08 | 82±20 | 45 | |

| Wheat straw | 3.55±2.66 | 1787±35 | 28±20 | 43 |

| Wheat stubble | 21.1±1.9 | 89 | ||

| Wheat fire | 38.20 | 89 | ||

| Wheat | 44.1±7.4 | 89 | ||

| Wheat | 59.00 | 89 | ||

| Wheat | 35.00 | 89 | ||

| Cereal waster | 1400 | 35.00 | 53 | |

| Wheat residue | 2.62-8.97 | 959-1320 | 61.1-179 | 86 |

| Wheat residue | 0.59-2.04 | 1540-1614 | 26-64 | 87 |

| Wheat straw | 0.41 | 34.65 | 88 | |

| Defalt emission ratio | ||||

| Agricultural residue | 0.01 | 0.06 | 20 |

The versatility of CO2e is that it can be a universal mechanism of measurement which may be applied to help us avoid The Tragedy of the Commons, and furthermore which may be used to eliminate the market biasing effect of subsidies. For example, imagine that, in attempting to avoid The Tragedy of the Commons, a government would like to tax the negative impact of emissions from antiquated power generation operations and use the funds to research alternative fuels.

Without measuring CO2e, the government in question could attempt to modify behavior in a few different ways, all of which are somewhat removed from the actual goal of reducing damaging emissions:

- Tax on a per-site basis. This is flawed in that a power company could have a shuttered facility which is in no way contributing to the negative impact of carbon emissions. Furthermore, the emissions of the restricted class of plants could be drastically different, yet they would all be taxed in the same way.

- Tax the revenue of the site. This approach is difficult in that the accounting can be quite complex, and therefore prone to loopholes.

- Subsidize clean energy. This may sound appealing, but consider that these subsidies are reducing price signals in the market, and therefore distorting market balance. This would also not deter a profitable company with antiquated plants from continuing their operations.

- ... and so on

Taxing CO2e emissions directly, on the other hand, would be considered a Pigovian tax, so named for British economist, Arthur. C. Pigou. Pigovian taxes are defined by the shared trait that they are designed to mitigate "negative externalities" (such as overgrazing, or greenhouse gas emissions) with the application of taxes specifically valued to offset the negative impacts. If you think back to The Tragedy of the Commons, it is an almost perfect parable of negative externalities: an activity where individual use of a shared resource is of detriment to others. In their purest form, we may think of Pigovian taxes as not artificially choosing "winners or losers" as subsidies may, but simply acting as an unbiased, unemotional accountant. These taxes essentially say, "You can build whatever kind of powerplant you prefer, but you will pay your share of any damage to shared resources."

The classic issue with Pigovian taxes is the valuation of the negative externality, essentially placing value on the erosion of a shared resource which is already difficult to valuate. For example, imagine placing a value on the shared visual damage wrought by a new residential development in a picturesque area, or the Pigovian price tag of a kilogram of carbon emissions. These are not easy determinations, but they may indeed change the landscape of daily life in the coming decades.

Professor Robert H. Frank, of Cornell University, wrote an excellent, short explanation of Pigovian taxes and mutual benefit for The New York Times.