Electric power in the United States is a $350 billion per year business and touches literally every corner of the economy. The "power grid" in North America is massive in scale and scope.

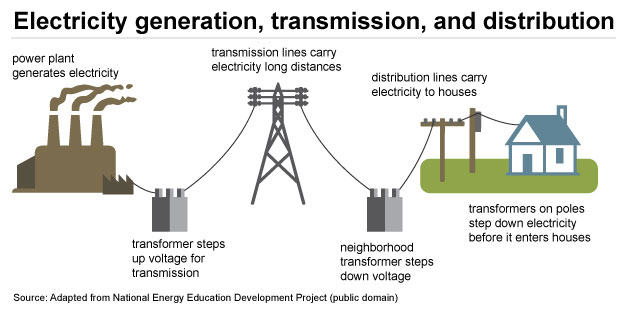

The figure below shows the three segments of the electricity supply chain - generation, transmission, and distribution. For nearly a century in the United States, there was one type of vertically integrated company performing all three of these functions. This company, called the "electric utility," generated its own electricity, moved that electricity over its own transmission lines within its geographic service area, and then delivered the power to its customers using its distribution lines. The electric utility usually had its prices, investments, and business practices tightly regulated by individual states. The federal government in the United States did not have a dominant role in the electric utility business until the process of deregulation and reorganization began in the 1990s.

This is a flowchart. Power plant generation > transformer which steps up voltage for transmission > transmission lines carry electricity long distances > neighborhood transformer steps down voltage > distribution lines carry electricity to houses > transformers on poles step down electricity before it enters houses.

Prior to the process of electricity restructuring, the primary players in the electric power business in the United States were vertically integrated utilities and their state regulators.

Electricity reforms in the United States began in the 1990s. Not all states elected to reform their electric utilities, but most of the states in the northeastern U.S., along with California and Texas, did choose to reform and restructure the electric utility business. Most states in the southern and western US did not choose to undertake electric utility reforms and still have vertically integrated utilities with tight state regulation.

Broadly, the process of electricity reform (sometimes called "deregulation" and sometimes called "restructuring") consisted of the following:

-

The vertically integrated electric utility was broken up into three separate companies - one each for generation, transmission, and distribution. Oftentimes, the same parent company owned all three businesses as independent subsidiaries.

-

Price regulation on power generation was removed or substantially loosened. Rather than charging regulated prices, power generation companies could charge whatever price the market would bear. These new electricity markets would be regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission rather than by the individual states.

-

Electric transmission would mostly retain its regulated pricing, but much responsibility for setting transmission prices was shifted away from the states, into the hands of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

-

Some financing processes for power plants were loosened, allowing for faster accounting depreciation of new equipment.

The process of electricity reform has dramatically widened the number of types of companies and regulatory agencies involved in electricity supply.

Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs)

Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs) are non-profit, public-benefit corporations that were created as a part of electricity restructuring in the United States, beginning in the 1990s. Some RTOs, such as PJM in the Mid-Atlantic states, were created from existing “power pools” dating back many decades (PJM was first organized in the 1920s). RTOs are regulated by FERC, not by the states. There are seven RTOs in the U.S., covering about half of the states' and roughly two-thirds of total U.S.'s annual electricity demand. Each RTO establishes its own rules and market structures, but there are many commonalities. Broadly, the RTO performs the following functions:

- management of the bulk power transmission system within its footprint;

- ensuring non-discriminatory access to the transmission grid by customers and suppliers;

- dispatch of generation assets within its footprint to keep supply and demand in balance;

- regional planning for generation and transmission (see below for limitations to this function);

- with the exception of the Southwest Power Pool (SPP), RTOs also run a number of markets for electric generation service.

RTOs have responsibility for ensuring reliability and adequacy of the power grid. They must perform regional planning, meaning that they determine where additional power lines and generators are required in order to maintain system reliability.