Lesson 8.1: Orebody Access

There are three common methods to access an orebody under deep cover. They are shafts, declines, and adits/drifts.

Shafts

A shaft is a vertical or nearly vertical opening driven from the surface to the deposit. The cross-section of a shaft is usually elliptical or circular, as these shapes are stronger than square or rectangular openings, provide less resistance to airflow, and maximize the useful space per dollar spent on the shaft. The diameter or dimensions of the opening are based on the purpose for which the shaft will be used, and the diameter can commonly range from around 6’ to 30’, and sizes outside of this range occur occasionally. The shaft may be used solely to hoist ore to the surface, provide ventilation, or to transport people and supplies. Commonly, shafts are partitioned and serve more than one purpose.

Declines

A decline can take the form of a slope, which is a straight opening driven at an angle, or a ramp, which is similar to a slope except that it is generally helical in shape. The angle of the slope, as well as the design radius and the angle of the ramp, depend on their intended use. The dimensions of a decline will depend on the purpose for which it is to be used. A slope may be outfitted with a belt conveyor to move ore out of the mine, or perhaps there will be track for rail haulage. The slope may be partitioned with a top and bottom compartment to facilitate multiple uses, including ventilation. A ramp, on the other hand, is used primarily for access, to move people, supplies, and ore between levels or to the surface, and it will be sized to accommodate the largest piece of equipment in use. The ramp may also be used for ventilation and utilities, e.g., electric power cables and water lines.

Adits/Drifts

Openings that are driven within the ore and follow the seam or vein are known as adits when they are driven in metalliferous veins or drifts when driven in coal and nonmetal seams. Functionally, there is little difference between a slope and a drift or adit. It’s simply that one, the slope, is driven in the country rock, i.e., the nonmineral-bearing rock around the ore, whereas the other, the adit or drift, is driven in the ore. In the past, it was common to find veins or seams that intersected the surface. The practice, as you would expect, was to begin mining the ore where it intersected the surface, and then to follow the vein or seam and continue mining. In some cases, this led under a mountain, in other cases, with a vein or seam that was dipping at some angle, the driven opening could go quite deep. Regardless, the opening at the surface, or the entry point into the mine, is known as an adit or drift. Thus, when you hear the term slope, you will know how that differs from drift or adit. To be honest with you, I find some of these definitions and the subtle differences among them to be a bit tedious. But, they are in common use, and you should know what they mean, and you should use the correct term.

And number 4: the Box Cut

There is a fourth means of access that is used infrequently, but is common enough to warrant its own category. It is known as a box cut. You may recall learning this term earlier, as this term is taken from surface mining, and specifically the open cast mining method known as area mining. In that method, an initial cut is made to start the process, and the material from this cut is hauled away. Typically, this cut looks like a box: it is few hundred feet wide and several hundred feet in length, and may be up to a few hundred feet in depth. However, the dimensions are specific to the application. You’ll find this method of access being used in coal and limestone, and often the depth of the box is less than 100’. The idea is to have the floor of the box at the same level as the seam. This allows openings to be driven into the seam. And what would these openings be called? Yes, drifts. Of course, roadways need to be constructed to allow equipment, supplies, and personnel to be transported down into the box cut, and into the mine. Sometimes, the box will be enlarged to allow placement of buildings, crushers, and so on within the box cut.

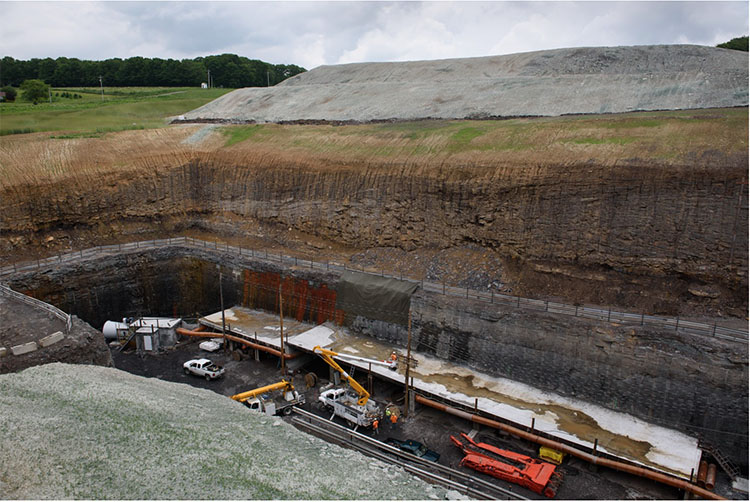

Here is a photo of a box cut to access a coal seam. You can see the overburden that was removed and carefully place in the background. Note the overburden layers and the rock overlying the coal seam. In the front left side of the picture is an access road into the box, although it is difficult to see clearly.

The choice of an access method is generally limited. The following list illustrates the factors that go into the selection.

- If the seam or vein intersects the surface, a drift or adit will be the choice.

- If the seam is close to the surface, i.e., typically within a few hundred feet, a box cut will receive serious consideration.

- The construction cost of a shaft is about three times the cost of a slope; however, the construction footage of a slope is generally at least three times that of a shaft.

- The deeper the orebody, the more likely that a shaft will be used.

- Transporting large equipment into a mine is more easily accomplished with a slope rather than a shaft. Large equipment must be cut into pieces and reassembled underground if there is no slope access.

- Construction of a slope is more challenging in difficult ground conditions, and could sway the decision to choose a shaft.

- A shaft limits the materials handling to batch operations, which is a serious limitation, as discussed earlier in the semester.

- Quite a bit of real estate is required to put in a slope, and a ramp can be constructed under a much smaller surface footprint.

- A ramp precludes continuous haulage, which can be a disadvantage.

- Coal mines require two means of access, and it is common for deep mines to use both a slope and a shaft. This allows them to realize the benefits of both means of access.

This is not an exhaustive list of considerations, but it is representative. As you progress in your studies and learn more about ground control, ventilation, and materials handling, the decision criteria will become even clearer to you. These openings must serve as primary conduits for ventilating air – either fresh air intakes or exhaust air returns, and that will impact the size and configuration of the choice. The material handling options, which center around batch versus continuous, will be important factors in the decision, as well as the need to move very large equipment on a regular basis. You’ll recall from our discussion of auxiliary operations that we have several materials handling options. These can be summarized here by access type.

| Shaft | Slope/Drift/Adit | Ramp | Box Cut |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hoist | Rail | Rubber-tired haulage | Rail |

| Vertical belt | Belt | Belt | |

| Elevator | Inclined hoist | Rubber-tired haulage | |

| Rubber-tired haulage |

Placement of the Access Opening

What about the placement of the access opening on the property? All things being equal, you’d probably want the access to be near the centroid of the orebody. The location of roads and rail service to your property could affect the decision, as could topography. You wouldn’t want your shaft to be located at the lowest natural drainage point of your property, and permitting constraints limit the placement as well. In general, you cannot place an access opening down dip from the seam that you are mining because any water accumulation in the mine would then drain out of the mine. That can be an environmental issue that you have to address. Ground conditions may affect your placement decision as well. Unless there are overriding circumstances, logistical considerations will weigh heavily in your decision of where to locate the shaft, slope, ramp, or box cut.