Join Dr. Alley and his team as they take you on "virtual tours" of National Parks and other locations that illustrate some of the key ideas and concepts being covered in Unit 5.

TECH NOTE - Click on the first thumbnail below to begin the slideshow. To proceed to the next image, move the mouse over the picture until the "next" and "previous" buttons appear ON the image or simply use the arrow keys.

Virtual Field Trip #1: Good Things in the Badlands

Image 1: Sunrise over the Badlands. A first look at breaking rocks to make sediment, and transporting that sediment to make beautiful and informative places.

Image 2: Children sitting on jackalope statue at Wall Drug tourist area in Badlands. Most folks who drive to the Badlands are enticed by the seemingly endless signs for a particularly well-known tourist trap, shown here.

Image 3: Badlands rock landscape. The badlands are muds and sand beds put down by ancient rivers draining the Rockies, together with volcanic ashes blown in on the wind. All of these materials were made by the breakdown of older rocks in the Rockies.

Image 4: Badlands clay landscape. The clays of Badlands soils expand and contract as they wet and dry, tearing out plant roots. Flat areas maintain vegetation, but steep areas are mostly bare sediment.

Image 5: Large weathered rocks in Badlands. Breakdown of rocks to make smaller pieces and new types such as clay minerals is called weathering. Movement of these smaller pieces is called transport. Together, weathering and transport make erosion.

Image 6: Tree roots in Bryce Canyon exposed by soil erosion. Finding evidence of erosion is not hard. This tree, on the rim of Bryce Canyon, started with its roots covered by soil, but the soil has eroded away. The very soft, steep rocks here have eroded by more than a foot in the few decades of this tree’s life.

Image 7: Ancestral Puebloan rock carving showing surface flaking. Arrow points to half-spiral. Petrified Forest National Park. Ancestral Puebloan people carved this rock in Petrified Forest National Park almost a millennium ago. A little of the rock surface has flaked off since then; the artists did not carve a half-spiral on the left (arrow added).

Image 8: Ancestral Puebloan rock carving damaged by fall of rock. Petrified Forest National Park. As in the previous picture, the thousand-year-old artwork of Ancestral Puebloan people has been damaged a little by fall of rock, showing that rocks do change, but slowly.

Image 9: Rock split in two as a result of frost grown in crack. Coast of Greenland. And in a very different environment, in the remoteness of the coast of Greenland, frost growth in a crack has split this rock in two. The rock is in the deposits from about 1850, and most of its surrounding rocks have not been split, giving some insight to the rate of weathering.

Virtual Field Trip #2: The Redwoods and Death Valley

Image 1: Two contrasting photos. Top photo of Redwoods, bottom photo of Death Valley. A Contrast in Weather… Redwoods and Death Valley. Some pretty pictures by R. Alley, with a message at the end.

Image 2: Close-up of Sequoia trees in Redwood National Park. Redwood National Park is another of the parks established primarily for biological reasons. Sequoia sempervirens, the ever-living sequoia, will live for two millennia, and then sprout new trees from its fallen trunk.

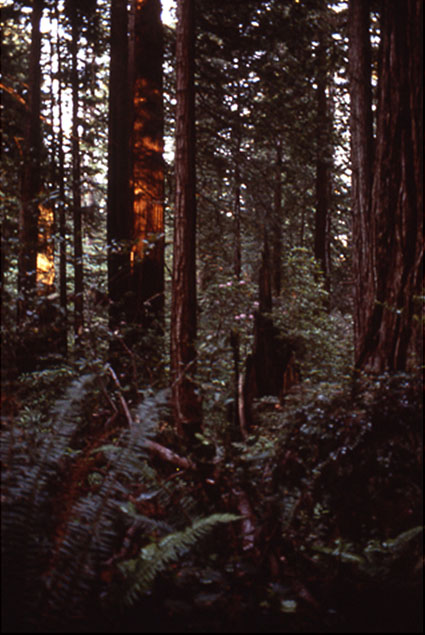

Image 3: Redwood forest, with ferns, rhododendron and azaleas in the understory. The redwood forest, with ferns, rhododendron and azaleas in the understory, look like a magnified version of an eastern hemlock forest.

Image 4: Rhododendron in Redwoods. The acids in redwood needles help produce soils that favor rhododendron (shown here) and ferns, as well as more redwoods.

Image 5: Sequoia tree standing more than 370 feet tall. Reaching heights of more than 370 feet (well more than a football-field standing on end), the redwoods are the world’s tallest trees.

Image 6: Ocean view at the Redwood coast. The redwood coast is rainy and foggy; the huge trees couldn’t exist in a drier environment. The coast is also beautiful.

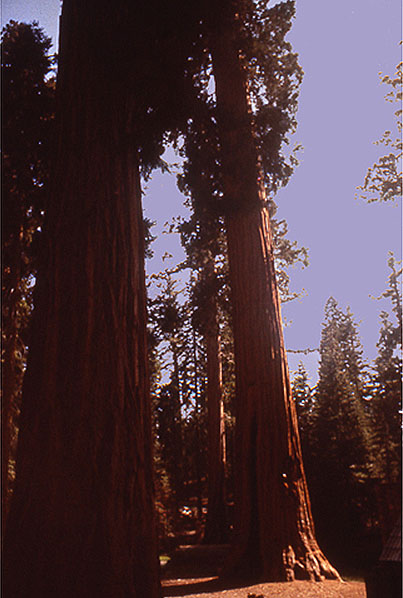

Image 7: Giant Sequoias representative of those found in Yosemite, Kings Canyon and Sequoia National Parks. Up the mountains from the redwoods are the giant sequoias of Yosemite, Kings Canyon and Sequoia National Parks. Although not as tall as the redwoods, these trees are more massive--generally considered the largest living things on Earth--and live more than a millennium longer.

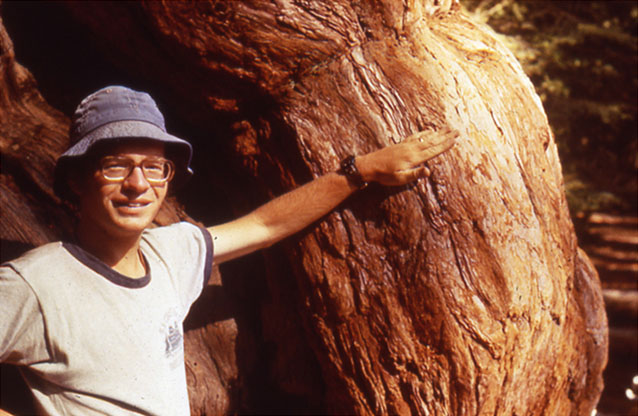

Image 8: Close-up of man standing next to Sequoia tree, showing thick bark. The thick bark of the sequoias is nearly fireproof. The trees need fire to clear out faster-growing trees so young sequoias have room to grow, and to trigger sprouting of those young sequoias.

Image 9: Death Valley landscape. At about the same latitude as the sequoias and redwoods, and with the same sunshine above the clouds, is Death Valley and the rest of the Great Basin. This huge weather difference is discussed in the textbook--Death Valley is warmed by tropical sunshine, set loose by redwoods rain.

Image 10: Topographical map showing Coast Redwood range with arrow pointing to Death Valley behind the mountain range. Link: http://data2.itc.nps.gov/hafe/hfc/carto-detail.cfm?Alpha=REDW# At about the same latitude as the sequoias and redwoods, and with the same sunshine above the clouds, is Death Valley and the rest of the Great Basin. This huge weather difference is discussed in the textbook--Death Valley is warmed by tropical sunshine, set loose by redwoods rain.

Virtual Field Trip #3: The Grand Tetons!

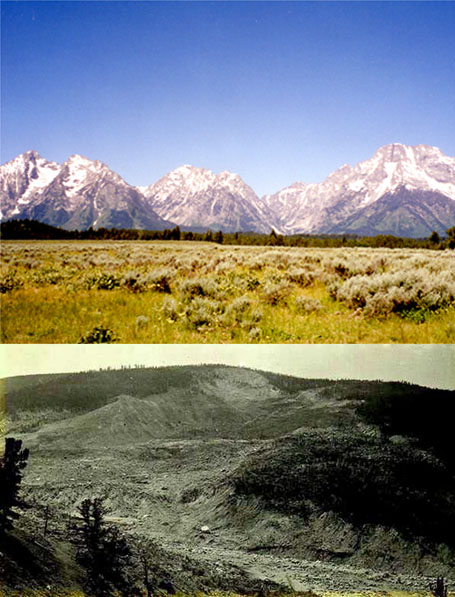

Image 1: Two contrasting images: Top photo of Grand Tetons. Bottom photo of Gros Ventre slide. (Top) The Grand Tetons--Surely one of the finest views in the west (Bottom) And the Gros Ventre slide--A reminder that the west is ever-changing.

Image 2: The Grand Tetons with evergreens in the foreground. The Grand Tetons. This is real mountain scenery.

Image 3: Close-up of Grand Tetons showing pull-apart-type faulting. Pull-apart-type faulting has dropped the valley and raised the mountains a total of several miles.

Image 4: Close-up of Grand Teton peaks with dark thunder clouds above. Rockfalls are common, especially during intense summer thunderstorms.

Image 5: Mount Moran with Darn Yellow Composites (wildflowers) in foreground. Mount Moran is framed by summer wildflowers (DYCs, or darn yellow composites, because yellow composites are often so hard to identify accurately).

Image 6: Oxbow Bend with view of Mt. Moran and other Tetons in the background. Oxbow Bend is a favorite site for viewing Mt. Moran and the rest of the Tetons.

Image 7: Grand Tetons with lake in the forefront. Numerous lakes, many glacier-carved, dot the park.

Image 8: Gros Ventre slide, near the Grand Tetons. Historical photograph of the Gros Ventre slide, near the Grand Tetons.

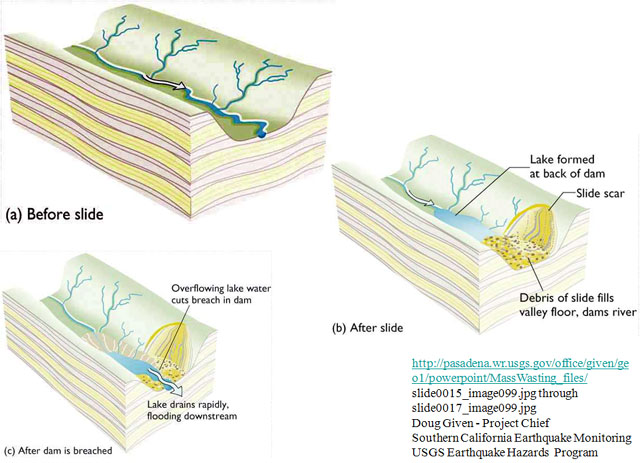

Image 9: Cross-section drawings of before Gros Ventre slide, after the slide, and after dam is breached.

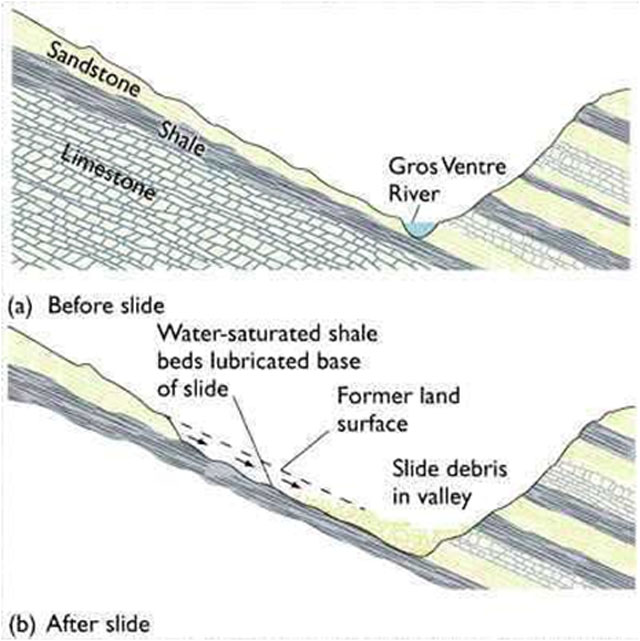

Image 10: Valley cross-section drawing showing geological setting of the Gros ventre slide. Valley cross-section showing geological setting of the Gros Ventre slide.

Image 11: Historical photo of lower slide lake shows a person standing on the roof of a submerged building. Historical photo of lower slide lake. Catastrophic drainage of the slide-dammed lake destroyed the town of Kelly, killing six and destroying the hotel, mercantile store, automobile garage, blacksmith shop, livery stable, and homes, but sparing the Episcopal Church and local school.

Virtual Field Trip #4: Landslides!

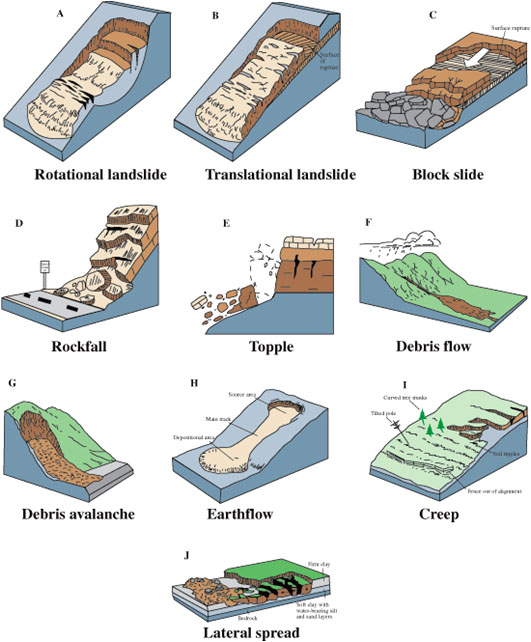

Image 1: Drawings labeled A through J representing 10 types of mass movements. http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2004/3072/images/Fig3grouping-2LG.jpg. There are many types of mass movements, ranging from hundreds of miles per hour to less than an inch per year, and from whole mountains to single grains of sand.

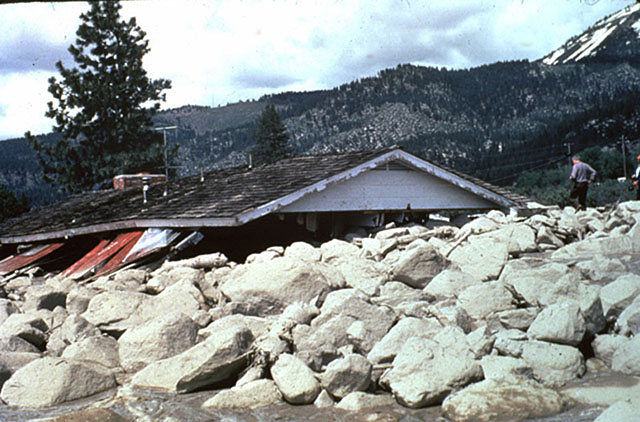

Image 2: Slide Mountain, Nevada. House buried beneath slide, only roof above surface. http://landslides.usgs.gov/html_files/landslides/slides/slide2.htm. Slide Mountain, Nevada. Snowmelt-triggered debris flow, May, 1983, killed one and injured several. USGS had publicly identified the hazard a decade earlier, but good science is often ignored.

Image 3: A car in the mud of a 1994 landslide near McClure Pass, Colorado. http://landslides.usgs.gov/html_files/landslides/slides/slide11.htm Photograph by Terry Taylor, Colorado State Patrol. Landslide near McClure Pass, Colorado, 1994. The driver did not see this nighttime slide in time to stop, but fortunately was not injured

.Image 4: 1995 Landslide under the only road to lodge of Zion National Park. http://landslides.usgs.gov/html_files/landslides/slides/slide19.htm. Photograph by R.L. Schuster, USGS Landslide under the only road to lodge of Zion National Park, April, 1995, stranded 100 people for two days. The broken sewer pipe, shown in lower part of photo, didn’t help.

Image 5: Aerial view of 1995 landslide at La Conchita, California along highway 101. http://landslides.usgs.gov/html_files/landslides/slides/slide21.htm. Photo by R.L. Schuster, U.S. Geological Survey. Spring, 1995 landslide at La Conchita, California, south of Santa Barbara along highway 101. Many homes were destroyed, but no one was injured.

Image 6: Home crumbled and destroyed by La Conchita, California slide. http://landslides.usgs.gov/html_files/landslides/slides/slide24.htm Photograph by R.L. Schuster, U.S. Geological Survey Home destroyed by La Conchita, California slide from previous picture.

Image 7: 1981 Winter Park, Florida sink hole opening. Car, truck and destroyed building in the sink hole. Caption: http://landslides.usgs.gov/html_files/landslides/slides/slide10.htm This is the Winter Park, Florida sinkhole, which opened in one day in 1981. We’ll return to sinkholes when we visit caves, which occur with sinkholes.

Image 8: Half-mile-high landslide scar, Tracy Arm/Ford’s-Terror Wilderness Area, Alaska. Caption: Half-mile-high landslide scar, Tracy Arm/Ford’s-Terror Wilderness Area, Alaska. Steep slopes caused by mountain building or rapid erosion (in this case, by glaciers) often fail catastrophically. A slide similar to this made the immense tsunami in nearby Lituya Bay that we discussed last week. Photo by R. Alley

Image 9: Landslide near Sitka, Alaska. Caption: Most landslides don’t make the news, such as this one near Sitka, Alaska. Photo by R. Alley.

Image 10: Numerous landslides on the mile-high, glacially carved cliffs in Milford Sound, New Zealand. Caption: Milford Sound, New Zealand. The numerous landslides down the mile-high, glacially carved cliffs give it the pretty, striped appearance. Photo by R. Alley.

Word Document of Unit 5 V-trips

Want to see more?

Here are some optional vTrips you might also want to explore! (No, these won't be on the quiz!)

Death Valley National Park

(Provided by UCGS)

Grand Tetons National Park

(Provided by UCGS)