Materiality and Sustainability Imperatives

What Was Once Intangible Now Becomes Immediate

In discussing sustainability with colleagues–or frankly anyone, after discovering you work in the field of sustainability–you may find two questions tend to be asked in one form or another:

- "Where is all of this sustainability stuff coming from?"

- "What does it mean to our organization?"

In both cases, materiality is a significant part of the answer, and there are two definitions of materiality which are equally important in stating our case: the formal Supreme Court definition of materiality in reference to financial reporting, and the functional definition of materiality as applied to each organization. Both are extremely important for shaping sustainability within the organization, and these two cores of materiality tend to be invaluable in explaining sustainability to anyone from a classroom of 10-year-olds to your organization's leadership (which may have strikingly similar attention spans!).

What is fascinating about the two cores of materiality is that they tend to capture much of the essence of sustainability as practiced in organizations today, as the Supreme Court definition captures the external requirement, and the functional definition tends to capture internal imperatives and what makes the sustainability program unique to the organization. For this reason, materiality is also what makes the practice of sustainability so varied from one organization to another, as there is no standard "sustainability playbook" an organization can dust off and execute. For example, an excellent sustainability program for Nike would, at best, be a poor fit for Ford.

The Formal Supreme Court Definition of Materiality

In 1976, the U.S. Supreme Court rendered a judgment in TSC Industries, Inc. v. Northway, Inc, creating a more defined definition of what information should indeed be considered material in financial disclosures, especially for publicly traded companies.

In summary, the case dealt with a merger between National Industries and TSC Industries where there had been some intermingling of board members and a significant share of company stock had traded hands before a merger vote, but this interaction was not disclosed to shareholders. In the case, Northway, a TSC shareholder, argued that the various pre-merger intermingling of TSC and National could have been construed as a conflict of interest, and would have caused them to therefore vote against the merger.

The earlier definition of materiality, as interpreted by the Court of Appeals in this case and recalled in the Supreme Court judgment was that, "...material facts include all facts which a reasonable shareholder might consider important." The Supreme Court believed that this Court of Appeals interpretation of material information was far too broad, and in a unanimous decision, Justice Thurgood Marshall penned an extremely important line in the Case Opinion:

...there must be a substantial likelihood that the disclosure of the omitted fact would have been viewed by the reasonable investor as having significantly altered the "total mix" of information made available.

This simple line would, in time, be the sentence that launched a thousand sustainability programs. This line is why sustainability programs are no longer "optional" for publicly traded companies, and why those publicly traded companies, in turn, "push down" sustainability requirements and audits into their suppliers. What those third-party suppliers do–for example, manufacturing shoes with child or indentured labor–is indeed a risk and material concern for the company purchasing from that supplier.

Let's all put on our black hats and question this in practice.

With our blackest-black CFO hats now firmly secured atop our collective consciousness, let's assert that nothing a company does with 'carbon emissions' or 'recycling soda cans' is going to change either the top or bottom line of the company, and that only "activist" investors would ever care about sustainability in determining whether to invest in a company or not.

What is the likelihood that not disclosing information such as the following would 'significantly alter the total mix of information made available to a reasonable investor'?

- that 20% of a company's branded apparel (accounting for 40% of revenue) is made in factories utilizing child labor

- that a highly-respected premium consumer brand is a human rights violator

- that a company has nearly 10x the reportable injuries of peers

- that a company suppressed whistleblowers from reporting a potentially-fatal product flaw

- that a company's product portfolio energy performance lags peers by 50%, with no plans to improve

- that a company relying heavily on green badging and "sustainable sourcing" has absolutely no proof of claims

If these types of issues indeed affect the "total mix" of information made available and have bearing on share value, then sustainability aspects are indeed material to the organization... and are, therefore, legally required public disclosures.

The Sustainable Accounting Standards Board (commonly referred to as SASB in text, pronounced 'sass-bee'), a 501(c)3 created to help create uniform standards for materiality disclosures (and chaired by Michael Bloomberg), further illustrates the point, bridging the Supreme Court finding with existing required disclosures for public companies (SASB, 2015):

Disclosure of material sustainability issues is important to investors, companies, regulators and the public for the following reasons:

- The SEC already requires disclosure of material issues in the Form 10-K, 20-F and other filings in use by investors.

- Institutional investors have a fiduciary duty that requires them to consider material issues.

- Companies have limited resources, and must therefore focus on disclosing and managing the performance of material issues.

- The potential for negative social and environmental impacts of operations can present high costs to investors, companies and society.

The Functional Definition of Materiality

GRI offers a short explanation of materiality principle as applied to an organization's sustainability program, stating it as aspects that "Reflect the organization’s significant economic, environmental and social impacts; or Substantively influence the assessments and decisions of stakeholders" (GRI, 2013). While this is certainly accurate, I tend to favor the more picturable definition of the GRI Materiality Tests:

In defining material Aspects, the organization takes into account the following factors:

- Reasonably estimable sustainability impacts, risks, or opportunities (such as global warming, HIV-AIDS, poverty) identified through sound investigation by people with recognized expertise, or by expert bodies with recognized credentials in the field

- Main sustainability interests and topics, and Indicators raised by stakeholders (such as vulnerable groups within local communities, civil society)

- The main topics and future challenges for the sector reported by peers and competitors

- Relevant laws, regulations, international agreements, or voluntary agreements with strategic significance to the organization and its stakeholders

- Key organizational values, policies, strategies, operational management systems, goals, and targets

- The interests and expectations of stakeholders specifically invested in the success of the organization (such as employees, shareholders, and suppliers)

- Significant risks to the organization

- Critical factors for enabling organizational success

- The core competencies of the organization and the manner in which they may or could contribute to sustainable development

Capturing Materiality: The Materiality Matrix

To set the boundaries of what aspects and considerations an organization considers specifically material to their operation, they create a materiality matrix. What is interesting about this chart or table is that it bridges the two cores of materiality in a rather illustrative and easy to understand format. We will do a bit of comparative analysis in a moment, but I'd like to briefly cover the process underlying the creation of a materiality matrix.

The organization begins by creating a full list of issues and aspects it faces, doing so both by internal meetings and external stakeholder engagement. These issues could range from minor concerns raised by an NGO to aspects which could potentially trigger the Supreme Court definition of materiality insofar as the omission of the information could alter "the total mix of information made available." Each aspect's materiality is then rated according to two standards, arranged on the X and Y axis:

In the X axis, usually referred to as "Organizational relevance" or "Organizational impact," the organization rates the importance of a given issue to its operations and viability. The act of creating this evaluation tends to be voted and argued by a broad team representing the various functions of the organization from marketing to EHS. Some companies are extremely scientific in this regard, creating weightings for the various functions based on their knowledge of each specific issue at hand, while other organizations essentially throw the issues up on the wall and vote to create a rank order.

In the Y axis, usually referred to as "Stakeholder concern" or "Stakeholder relevance," the organization then engages external stakeholder groups to understand how they would rate the importance of a given aspect.

Interestingly, there are issues which organizations consider a significant risk given their knowledge of operations, but which stakeholders may have no idea of, and vice versa. This is what makes materiality matrices so powerful, as they represent the entire field of issues and aspects to be considered, in turn guiding them toward the most important for both the organization and stakeholders.

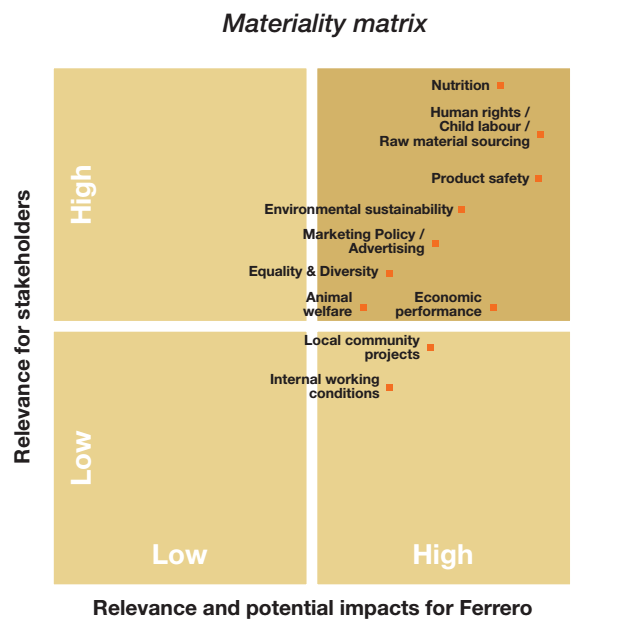

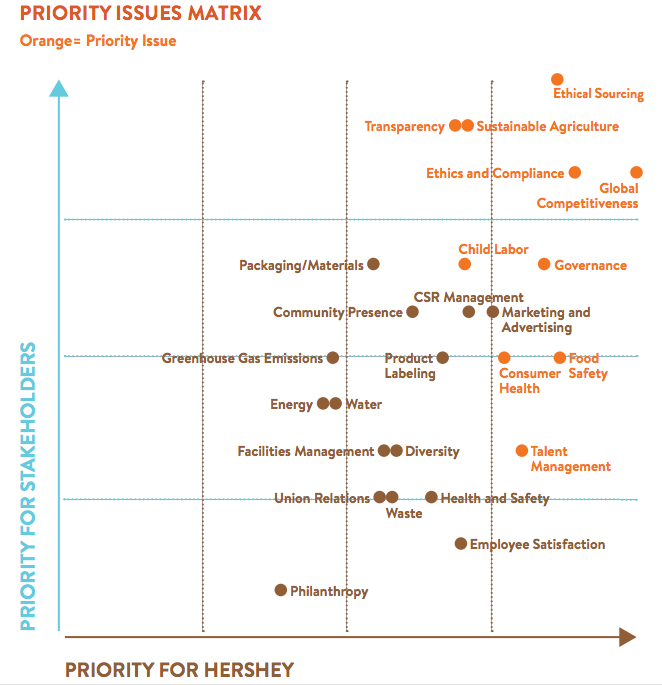

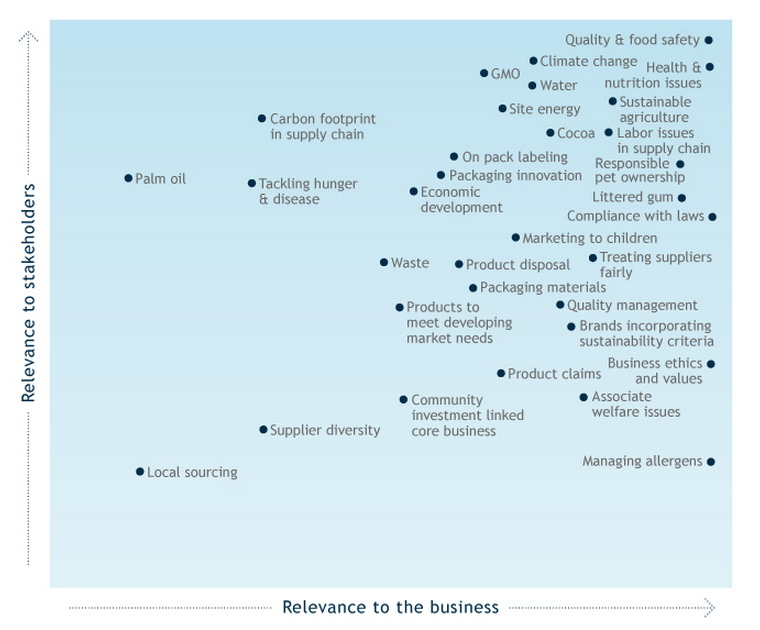

Similarities and Differences in Materiality: An Example in Chocolate

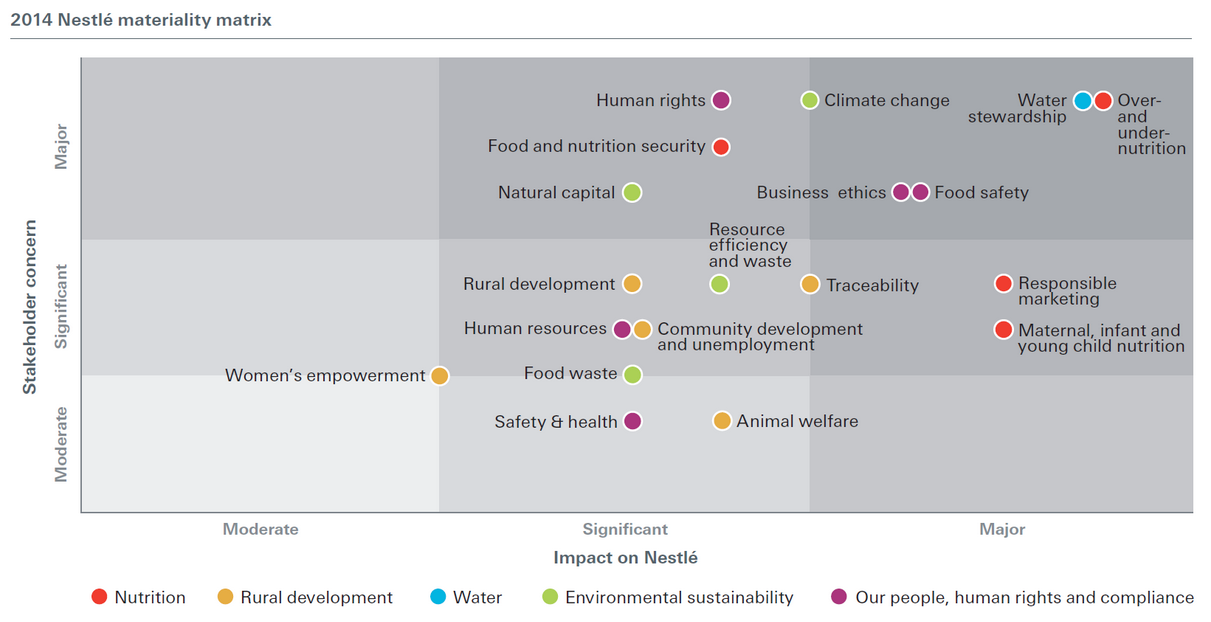

To illustrate how varied material issues can be in similar organizations, let's examine the materiality matrices of four of the world's leading chocolate companies: Mars, Nestle, Hershey, and Ferrero. As we will explore in later lessons, comparative analysis of materiality matrices is an excellent way to unearth shared issues and opportunities for innovation, as well as revealing aspects an organization may be ignoring that its peers are addressing.

Check Your Understanding

Look through the four materiality matrices below and consider underlying similarities and differences.

- Is there untapped potential or shared need which could be used as a platform for innovation?

- Are there issues being ignored based on your understanding of the industry?

- Any interesting disconnects or ratings which would merit further exploration?

- Are there potential entry points to displace existing suppliers or reinforce existing relationships?

If you would like, jot a few notes below... and then click the link to reveal sample areas of interest.

Click for areas of potential interest.

- Health/Nutrition is a top 2 concern for all companies, except Hershey's, where it is ranked below aspects like "Governance" and "CSR Management" for stakeholders, which is odd given the heavy public emphasis on obesity, food deserts, and other nutritional concerns. Furthermore, Hershey itself shows it as their #6 issue. This is interesting and bears research.

- All have some flavor of food/product safety in mid-pack, but Ferrero rates it as #2 overall. This may be a very fitting approach given their past experiences with their popular Kinder Eggs (chocolate eggs with toys inside) being banned in the US as a choking hazard for nearly 40 years. Notably, Ferrero takes a head-on approach to this issue, devoting 10 pages in its CSR specifically to Kinder Egg toys (beginning p.17 in linked PDF, p.30 on printed page).

- "Littered gum" is unique to Mars, and may be an interesting read. Another example of how tailored materiality is to each organization, even within subsets of industries (Mars owns Wrigley Gum).

- "Community presence/economic development" was a bit lower than one might expect, given that much of the supply chain is in impoverished areas. This may be either a function of robust programs in place, or simply of a lower relative priority. Bears investigation.

- There are a few "entrance points" for suppliers... "Packaging innovation" and "Packaging/Materials" both ranked fairly high priority for Mars and Hershey's, respectively. I would be interested, of course, if I were an industrial designer, packaging company, or existing supplier to either of those companies. Furthermore, these are likely bellwethers that those companies are also concerned with waste minimization in their own manufacturing operations... again, an opportunity. If I supplied disposable goods to those manufacturing operations, I would proactively reach out to see what we could do to understand/partner/improve performance.

- 'Responsible marketing' is a fairly high priority all around, which would be interesting to anyone from an ad agency with specific expertise to a consumer behavior research firm proposing a study to understand what responsible marketing is.

If we wanted to deep dive, we could begin by breaking out equivalent issues in a pivot table or spreadsheet and looking at average ranks, etc. to find further "threads to pull."

As covered in the "areas of potential interest" link in the exercise above, when a company lists its organization-wide strategic and tactical needs in a tidily prioritized form, it acts as a beautiful opportunity to innovate, find entry points, identify needs, and even to deepen relationships.

Here's the metaphor I would like to use: Imagine if you were a contractor, and you could freely walk into every house in town, and every owner had clearly marked their construction needs (i.e., "energy savings," "new paint," "child safety improvements") along with how important each project was to their family. Not every project would fit your expertise or strategy, but you could imagine that maybe... perhaps... it might be possible to find some opportunity there.

Needless to say, we will be exploring how to leverage materiality in innovation and creating offerings in later Lessons.

An emerging tool for both setting and evaluating an organization's material aspects is the SASB Materiality Map, which seeks to standardize material aspects by industry and sub-industry, as well as weighting relative importance. It's an interesting tool, and you can take a look at an early version in the linked page (red "Launch Map" link lower on page).

While organizations will always have unique issues to address (for example Ferrero's emphasis on product safety due to Kinder Egg line), the adoption of materiality standards could at least help create uniformity for the core aspects to make comparisons and benchmarking a bit more straightforward.