Oil and Gas Exploration

For over a century, exploration for oil and gas—finding the next big field full of valuable fossil fuels—has involved locating oil and gas traps and drilling into them. Most commonly, this has involved “seismic” exploration (see the figure and explanation below). Nature figured out how to use this technique long before humans did. For example, a bat flying around in the dark “looking” for a moth to eat will make a noise, and listen to the echo off the moth, using the time and direction to locate the flying dinner. Dolphins can find their food the same way.

Video: Air Gun Vessel to find Oil (:55)

PRESENTER: If you're a bat, a nocturnal mammal looking for flying bugs, you make a noise, and you listen to the echo that comes back off of the bug. And then you know it's out there and where it is.

Humans have adapted similar sorts of technologies to look for oil. So in this case, being done in the ocean-- this is ocean water along here. And we have a ship going along, and it makes a noise. It uses an air gun. They used to use dynamite.

And the noise is bounced off of various layers down below and then is listened to back here. And by looking at how bright and how long and other things about the arrival, you can learn a lot about the rocks that are down underneath.

And people do this both on land and in the ocean. And they're looking for those special places where oil has accumulated, and we can go in and drill into it and get it.

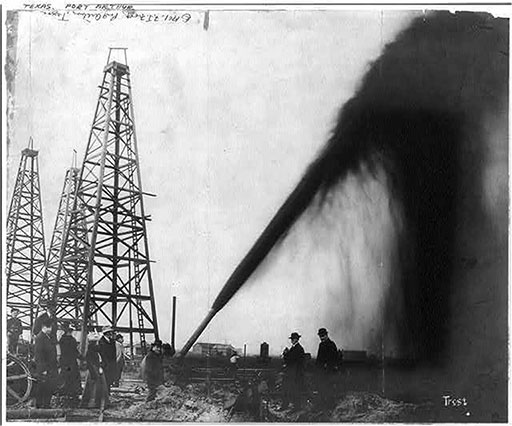

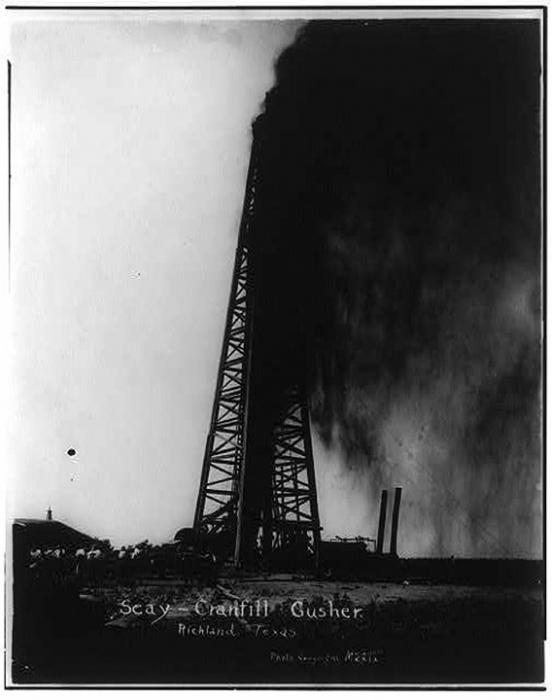

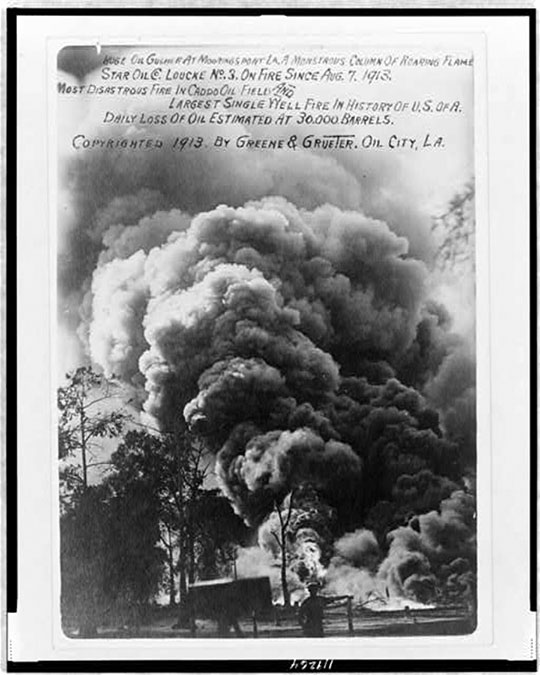

Oil explorers make noises, and listen to the reflections from layers in the Earth, using the time and direction to locate the oil-and-gas-filled traps. Then, drillers drill into the traps, and pump the oil and gas out. (Sometimes, the pressure is so high in the trap at the start that the oil comes out of the hole without being pumped, as a “gusher,” see figures below.)

But, soon, the pressure down there is reduced, and a pump is needed. Occasionally, a gusher catches on fire, with sometimes disastrous consequences, see the figure below.

Increasingly, a new technique is being used to recover oil and gas. Shale layers often have a lot of hydrocarbon left in them that did not escape in the past. Drillers have learned how to bore down to a shale layer, then turn the drill and bore along in the layer. When the hole is long enough, the drillers pump fluids at high pressure into the hole, breaking the shale in a process called “fracking” (from “fracturing”) that mimics the natural process by which oil and gas escaped the shale. Human use of this process was apparently first invented by a veteran of the US Civil War, Col. Edward Roberts, who saw the fractures in the ground caused by an exploding Confederate shell, and went on to patent the technique of using explosives to fracture rocks and allow more flow into wells. The technique has been improved in many ways since.

In many ways, fracking is not revolutionary but evolutionary from older techniques for recovering oil and gas. Under best practices, fracking probably isn’t inherently more risky or dangerous than those other methods. The biggest difference is that fracking is used to recover oil and gas that are spread out over large areas rather than having a large quantity concentrated in one place. So, fracking takes lots more drilling and pumping and installing pipelines in more places. Fracking is more likely to be in someone’s backyard, or near it, so there are more people seeing it and hearing it and complaining about it.

The more drilling there is, the more chances there are for mistakes to be made, contaminating groundwater or otherwise causing problems for neighbors. The drilling can also bring other problems, including lots of traffic. For example, back on Sept. 23, 2011, an article by Cliff White in the Centre Daily Times, State College, PA noted “A review of inspections performed by state police on commercial motor vehicles used in support of Marcellus Shale gas drilling operations in 2010 revealed 56 percent resulted in either the vehicle or driver being placed out of service for serious safety violations” but that “Thanks to heavy enforcement, the noncompliance rate has dropped to about 45 percent in the most recent study.” And, in the same article, “…a trooper in gas-rich Bradford County, said during the initial ramp-up of activity in that area a few years ago, almost all of the vehicles used for gas drilling-related purposes that he stopped had “some degree” of noncompliance.”)

Fracking is done with high-pressure fluids to which certain chemicals have been added, as noted above, and some of those chemicals may be dangerous to humans. The fracking fluids plus salty brines from the rocks “flow back” out of the wells, and these flowback fluids must be disposed of in some way. Much of that disposal recently has involved injecting the flowback fluids into the Earth in special deep wells. This has caused numerous earthquakes, some of them damaging. (See, for example, USGS: Induced Earthquakes.) Fluid injection for other reasons also has caused earthquakes; fracking is especially important in this only because it generates so much fluid that is being injected. Note that while fracking has probably triggered a few small earthquakes directly, the main cause of earthquakes is this injection of flowback fluids.

Fracking is likely to be with us for a long time. And, it is likely to remain at least somewhat controversial.

Video: Process of Fracking (1:01)

PRESENTER: If you're a bat, a nocturnal mammal looking for flying bugs, you make a noise, and you listen to the echo that comes back off of the bug. And then you know it's out there and where it is.

Humans have adapted similar sorts of technologies to look for oil. So in this case, being done in the ocean-- this is ocean water along here. And we have a ship going along, and it makes a noise. It uses an air gun. They used to use dynamite.

And the noise is bounced off of various layers down below and then is listened to back here. And by looking at how bright and how long and other things about the arrival, you can learn a lot about the rocks that are down underneath.

And people do this both on land and in the ocean. And they're looking for those special places where oil has accumulated, and we can go in and drill into it and get it.

![]() Earth: The Operators' Manual

Earth: The Operators' Manual

Fort Worth: Gas, Waste & Water (9:08)

If you want to see a little more on fracking, much of the clip is relevant, but the first 3 minutes and 40 seconds especially fit here.

Narrator: Today, in some ways,we're in danger of repeating the past. As the easy oil was all used up, we're drilling in challenging conditions up in the Arctic. We're considering an increasing reliance on tar sands, which are plentiful in our northern neighbor, Canada, but which are dirtier to process. But once more, America has been fortunate to find a new, abundant, domestic and potentially cleaner source of energy. Several regions from North Dakota to the mid-atlantic and northeastern states have large amounts of natural gas deep underground in shale rock formations. And the city of Fort Worth sits literally on top of the Barnett Shale. For the first time, a new source of energy is emerging when there's an awareness of the urgent need for sustainability. Can Fort Worth and America figure out how to make shale gas a significant part of our energy future, without repeating the mistakes of our energy past? Folks used to call this cowtown. Today, there are more than 2,000 gas wells right under the city of Fort Worth. This city's grown by 200,000 people in 10 years and estimate it will gain another 200,000...

Narrator: Rapid growth has brought congestion on the roads and pressure on fresh water resources at a time of record drought all across Texas. That has motivated the city to be part of the sustainability roundtable, bringing together developers and planners, energy executives, university researchers and even the commander of the local naval air station.

Mayor Price: We have to begin to develop a master vision for how do we be sustainable? It has to be a concentrated effort on every department's to think about their water use, their electric use.

Narrator: Roundtable members realize their push for sustainability is happening against the backdrop of the natural gas boom. It's quite remarkable how rapidly shale gas has developed from being basically zero percent of our production to being more than a third of our total natural gas production and going up.

Narrator: Depending on how quickly we use it, experts say America could have enough gas for several decades. To some, this is a huge bonanza.

Larry Broaden: We've found so much gas here and in other areas, that the price has been driven down.

Narrator: To others, shale gas is an environmental disaster waiting to happen. There has to be a more robust discussion with the public about risk and risk benefit. Very few discussions start that way. Most of them start with, "here's a source we must use." or "here's a source of energy we must not use." The real issue is, what is our desired end state?

Narrator: Geologists have known about shale gas for more than 20 years. But that didn't mean the gas was easy or economical to extract. In this industry video, you can see that hydraulic fracturing or fracking uses a mixture of water, sand and chemicals. This is injected deep underground to break up the rock and let the gas flow up to the surface more easily.

Mayor Price: We say we've been punching holes in the ground in Texas for 100 years.

Narrator: What was new was drilling down and then out horizontally, and the locations of the pad sites.

Mayor Price: We've been fracking wells for 50, but we've not done it in your backyard.

Narrator: Larry Brogdon is an oil and gas man who made money by acquiring and selling drilling rights. Now he teaches a course that touches on energy, economics, and environment at Texas Christian University. The economic benefit to this area in the last 10 years has been about over $65 billion.

Narrator: And when natural gas is used to generate electricity, some estimates are that it's 50% cleaner than coal. The advantage that natural gas has is that it's much lower carbon in terms of its footprint.

Narrator: Industry insiders say Americans need to recognize that the power we all use has to come from somewhere. Somebody goes over there and they flip on that light switch and they think they're just using electricity, well, natural gas is generating a whole lot of that electricity.

Narrator: However, public concern, here in Fort Worth and nationally, has focused on worries that the entire cycle of drilling, fracking, production and fluid disposal can contaminate drinking water, trigger earthquakes, and leak methane. It is an industrial activity, and that means the management of water. That means air quality. And the third thing is just the community impact, that suddenly areas that were not being developed for natural gas, now have this development coming in.

Narrator: Daniel Yergin was a member of a special committee tasked by the U.S. Secretary of Energy to study the potential environmental impacts of natural gas drilling. The committee came up with 20 recommendations of best practices, with number one being better sharing of information with the public. Number 14, disclosure of fracking fluids, and number 11, studies about possible methane contamination of water supplies. One has to do the full life cycle analysis, kind of cradle to grave kind of thing, to really understand where the points of vulnerability are including full environmental costs and to then weigh the risks and the benefits. And that will help us lay out what the panoply of sources would look like.

Narrator: Only if safeguards are in place can this fossil fuel really serve as a bridge to a more sustainable future. Right now best practices would focus on things like how do you handle the water that is produced out of the well as the result of hydraulic fracturing and making sure that it's disposed of in a very environmentally sound way. Narrator: As the name, hydraulic fracturing, implies, massive amounts of water are required for fracking and in Texas where water is a precious resource, this is a major concern. Water is huge, facing the city. And I think that water is one of those things that most people don't think long term about.

Narrator: Although mayor price says local breweries use more water than the drillers, with sustainability in mind, there's no reason why fracking has to use potable water. So now we're able to use reclaimed water to frack these wells and thereby use less of our potable water and it can take 3 million gallons of water to frack one well.

Narrator: Once thought of as a sewage treatment plant, Village Creek is now the water reclamation facility. Until recently, 50% of Fort Worth's potable water was used for irrigation. Now the city's distributing treated grey water in distinctive purple pipes to irrigate golf courses and playing fields and for industrial uses at the giant Dallas-Fort Worth Airport. Every day in the city of Fort Worth, about a million people put water down the drain. This is where it ends up.

Narrator: The water treatment process itself is becoming more sustainable and less energy-intensive. And in a twist, this new approach relies on a truly natural gas. Methane is the primary component of natural gas but it's also a by-product of our daily lives, found in human waste. One of the first steps in the process is to remove solids from the waste and put it into digesters where methane gas is generated. Under normal circumstances, you may consider methane to be a greenhouse gas which would be bad for the environment, but here we're using it as a renewable resource to power our engines, possibly getting up to as much as 90-95%, of the energy required for the operation of this facility.

Narrator: Fort Worth is aiming for sustainable growth and an energy boom without a following bust. But the energy we all surely need will more easily be found by tapping another resource that's found in Fort Worth, and every community. When we talk about energy, we talk about the various major energy sources. You talk about oil, natural gas, coal, nuclear. Increasingly also, of course, the renewables, wind and solar. But there's one fuel that gets left out of the discussion and yet it's one that has enormous impact on the future. That's the fifth fuel, energy efficiency, conservation.