Applying Lessons Learned from Kyoto

Scientists and policymakers alike understood that 2015 was the year a new global climate treaty needed to be forged in order to start aggressively addressing emissions at a level commensurate with what the science was telling us about necessary reductions to avoid catastrophic impacts.

Surprisingly, they came together and developed the Paris Agreement.

Key Differences Between the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement

- No differentiation between developed vs. developing - everyone agrees to binding commitments. Recall this was a key point for the United States going all the way back to the Kyoto Protocol. This aspect of the agreement was an important and historic step in international climate policy because it recognized the point that as it is one atmosphere, exempting some countries' impacts progress for all.

- Countries set their own targets - these were called Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) in the Agreement. After each country formally entered the Agreement, they are referred to as also referred to as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Each country submitted its INDCs as part of the Agreement to detail how it would achieve their emissions reduction goals per the Agreement. Put together as a whole, these pledges determine whether or not broader emissions goals will be met. Each country commits to self-reporting on its progress. This gives nations the flexibility to choose strategies that align with other strategic priorities and opportunities. These are the core of the Agreement because they outline how the emissions goals will be met. You can read more about INDCs from the World Resources Institute here and from the United Nations here.

- Degrees not percentages - The Paris Agreement focuses on limiting warming to no more than 2 degrees Celsius (relative to pre-industrial levels) by mid-century based on IPCC scientists' collective recommendation that this is really the threshold for avoiding the more catastrophic and irreversible impacts of climate change. It goes on to say more ambitiously that while limiting the warming to 2 degrees is good, containing it to 1.5 degrees is much better. This is further reiterated by the IPCC 2018 Special Report on 1.5 degrees. This WRI summary also explains how big a difference just half a degree can make. Focusing the conversation around degrees instead of percentages serves to ground the policy more in the science that's guiding it than the politics of what countries think they can or cannot do.

- Financial support for developing countries - establishes a minimum annual commitment of $100 billion (from developed countries) in climate finance by 2020 to assist Least Developed Countries (LDCs) in developing more sustainably and adapt to the impacts they're already committed to feeling. This is a fundamental step toward helping LDCs meet their climate goals, though it is likely inadequate, and even this target has not been reached (see here for some analysis from WRI). In addition, this is significantly less than the estimated $5.9 trillion of annual subsidies to fossil fuels. Further, funding that has been provided is possibly overstated. (For example, loans that incur debt are counted in full, and the debt payments are not considered.) Note that some of the $100 billion per year is an investment, not a donation, and ironically has contributed to more debt for already financially-strained budgets in low-income countries.

Nationally Determined Contributions - Are They Enough?

While an important step, some criticisms of the INDC process include:

- Lack of an enforcement mechanism. There is no penalty for not meeting targets or not having aggressive enough targets. This was also true of Kyoto and is an inherent shortcoming of these international treaties.

- As detailed above, the specificity of how to reach goals may vary widely among participating countries.

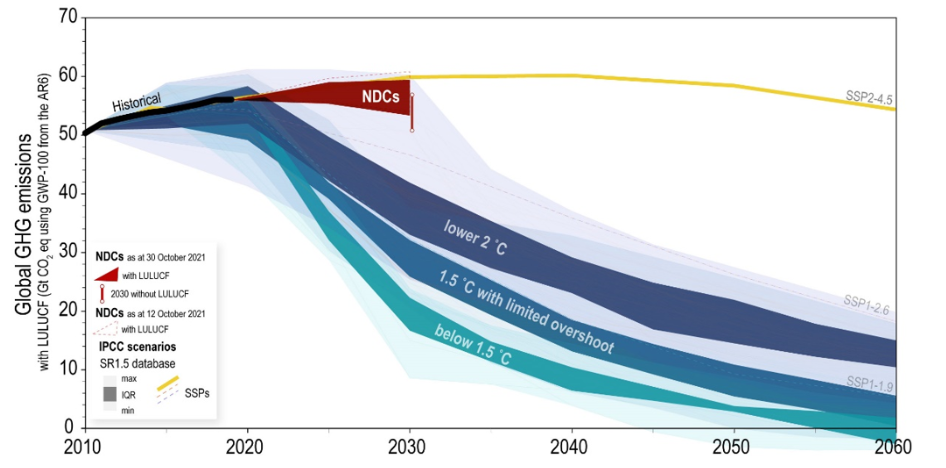

- Some contend the goals are not aggressive enough. In the most recent synthesis report, the UN determined that the updated NDCs taken as a whole would only reduce 2050 emissions levels by 70-79 percent, and further that they will only drop 5.2% by 2030 instead of the 25% required to be on a 2º C pathway or 45% to be on a 1.5º C pathway, and this assumes countries meet these goals. The full synthesis report is available here and the key findings here.

Credit: COP26 NDC Synthesis Report, 4 November 2021.

Credit: COP26 NDC Synthesis Report, 4 November 2021.

INDCs play an essential role in the ability of the Paris Agreement to achieve its goals. They provide the most detailed descriptions of how individual countries will meet emissions targets. However, some INDCs do this in a more detailed way than others, which is one criticism of the Agreement. Skim through the following INDCs and note the difference in detail between the countries' "plans" to reduce emissions in their 2021 INDC. Note also how much more detailed the 2021 plans are than the initial submissions in 2015. Clearly, progress has been made in the detail provided over the past 6 years, and climate goals have become more ambitious, but you can also see the difference in the details provided with regard to how to make this happen. All 2015 INDCs can be accessed here, and all 2021 INDCs can be accessed here.

"Differentiation, Financial Support, and the Paris Climate Talks" (Stowe, 2015) - this provides a nice summary of some of the key differences between Kyoto and Paris, which are really key to understanding the possibility for more extensive success. "Is the Paris rulebook sufficient for effective implementation of Paris Agreement?" (Sun, et al., 2022) provides a very detailed look at NDCs and whether or not the Paris Agreement is capable of reaching climate goals.