Interactive Maps

We briefly discussed interactive maps in the previous lesson on multivariate mapping—interactivity is often used to solve problems related to multivariate mapping, such as the challenge of fitting all the necessary data into one map frame. New technologies (most notably, mobile smart phones) have both increased the challenge of designing maps and contributed their own solutions. Creating a map that can be viewed on a 4.7-inch screen, for example, can be quite a difficult design problem. Yet, accessibility to mobile cell data and location-aware devices have enabled the creation of zoomable, pan-able, user specific maps—thus reducing the amount of map content required in-view at any one time.

Web maps such as the one in Figure 8.4.1, which allow the user to zoom and pan around the extent of the map, are commonly called slippy maps. While they may serve as general purpose maps themselves, these maps are most often used as basemaps that provide location context for a variety of thematic or functional overlays—such as the traffic volume data or navigational functionality of Google Maps.

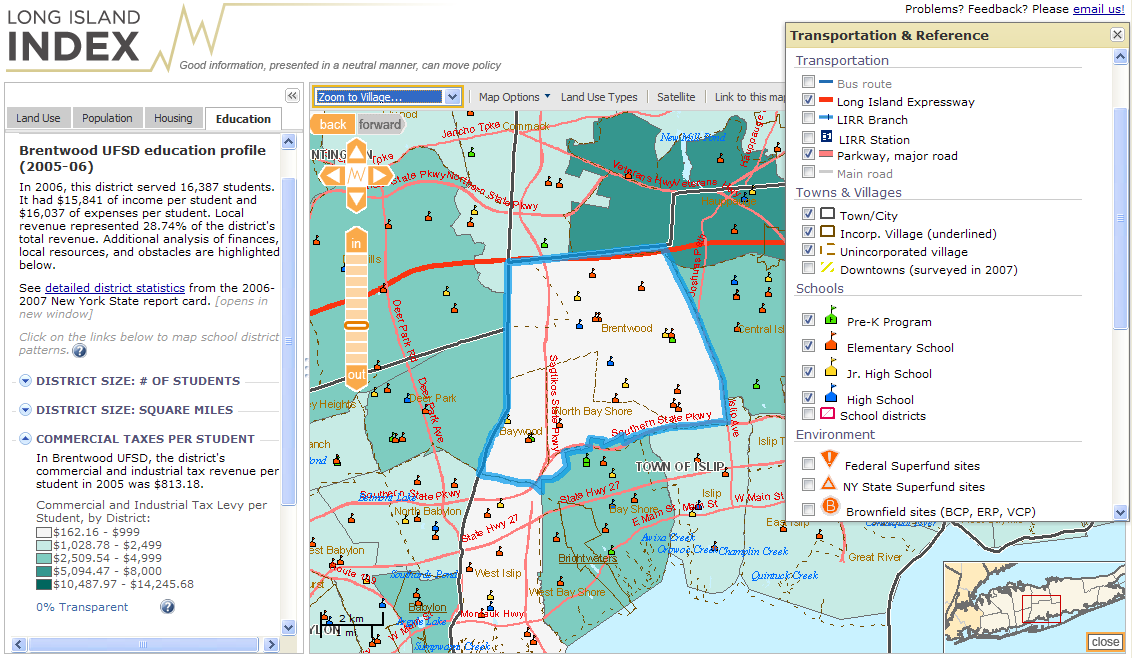

We often categorize interactive maps by the level of user interaction (low to high) they permit. Some maps allow only simple interactions such as panning or zooming, or perhaps show additional information about features on mouse hover or click. Others may be developed for expert users, and include the ability to search, filter, and analyze data, as well as the option to upload the user’s own data for exploration and analysis. Many interactive maps, such the one in Figure 8.4.2, fall somewhere in the middle of this continuum.

While the term interactive map is most often used to describe maps such as the one in Figure 8.4.2, other maps are better characterized as containing passive interactivity. These are maps that respond to actions of the user, though not in the traditional sense of a user interacting with tools via a map interface (Monmonier 2018). An example of this is an automotive personal navigation device (PND).

Though these devices also contain traditionally interactive components, they are primarily designed to respond to one particular user behavior—movement through space and time. Such mapping tools provide navigation, real-time traffic, and safety-zone warnings; some even provide advanced notifications such as lane departure warnings via unit-mounted cameras and other sensors.

Interactive maps have the potential to be useful in any geographic decision-making context, wherein the map can provide an appropriate interface between the human and the machine (Monmonier 2018). Due to the complexity of many of these products, however, the effectiveness of an interactive map is often dependent not only on the design of the map itself, but on its interface and related functions. This has made interactive map-making a particularly interdisciplinary subset of cartography, as successful approaches borrow increasingly from research in data visualization, human-computer interaction (HCI), and computer science. We will discuss the interface between maps and their users in more detail in Lesson 9.

Recommended Reading

Roth, Robert E. 2013. “Interactive Maps: What We Know and What We Need to Know.” Journal of Spatial Information Science 6: 59–115. doi:10.5311/JOSIS.2013.6.105.