In the previous section, we argued that landscapes are not only produced, but also consumed. More specifically, following Duncan and Duncan (1988), we took the position that landscapes can be thought of as texts that we can read. With this in mind, we can consider landscapes as having both authors (those who produce them) and readers (those who consume them).

As Bellentani (2016) demonstrates, the idea of landscape as text has its roots in the field of semiotics (the study of signs and symbols). Initially, in geography, the concept of landscape-as-text focused on authorship—but geographers assumed a single “author” with clear intentions that they wished to express in the landscape. Today, we put greater emphasis on the “readers” of landscape, arguing that readers have the ability to challenge the established meanings imposed on texts by their authors.

As Bellentani observes, individuals interpret texts “according to their own system of values and cultural identity” (2016, p. 83). When people share an identity, they may also interpret texts in similar ways, based on their shared knowledge and experiences. We refer to groups who share both an identity and an interpretation of texts as textual communities. This concept is important because it “is a meaning-based approach to consider readers as an active part of the meaning-making process” (Bellentani, 2016, p. 83).

In short, a person observing a landscape may see its features and interpret that landscape in ways that reflect their experiences in the world. In some cases, some aspect of their identity may lead them to interpret the landscape in a way that is shared by other members of that identity group. For example, people with a strong sense of place identity may collectively interpret signs of gentrification on the landscape of their hometown as a threat to the old order of things, while people who work as real estate developers may collectively see that same landscape as “blighted” and primed for redevelopment.

Now that we have some sense of what we mean by landscape as text, and of textual communities, we turn to what it means to read the landscape.

Foundations

Before we can talk about how to read landscapes, it’s helpful to understand what purpose this exercise serves, and what its limits are. A cultural landscape in its current form is always the product of a long series of overlapping choices made by people (collectively or individually), and mediated by the culture in which it exists. Careful reading can thus produce a wealth of information that extends from the present backwards in history.

It is also important to understand the difference between actively and passively reading the landscape. For many of us, the landscapes we see every day are so familiar that we have internalized their elements and hardly think about them. When navigating somewhere, we might actively seek a particular feature on the landscape (e.g., a specific building number, street sign, or landmark), but when we do so, we tend to disregard the rest. Some features, such as markings for lanes or parking spaces, or street signs, we use in a referential way, but their visual aspects are generally unremarkable unless something about them has changed (or unless we go to a place where the markings are stylistically different. This kind of engagement with the landscape is passive, and it is likely only to reveal the most obvious information.

Actively reading the landscape is a process that requires both an attention to detail and the ability to understand the specific collection of features as a whole. For example, focusing on a single element of a landscape, as in figure 6.7a below, tells us only that there is a Shake Shack somewhere in the world.

Yet, as figure 6.7b shows us, when we consider that single element with regard to other elements in the landscape, we are better able to situate it. In this case, the presence of signage in Turkish and the Turkcell banner in the upper right hand corner indicate that this is part of the Turkish landscape. Yet the elements in isolation tell us little; when we (actively) synthesize those elements, we might notice first, that there is a US-based fast food restaurant in this neighborhood, and second, that it belongs to one of the smaller American fast food chains. This might suggest to us first that this is a tourism-dependent area, and second, that there are American tourist dollars flowing into this landscape. (This was a Shake Shack that Dr. Livecchi encountered on İstiklal Caddesi during a visit to Istanbul in 2016. To the best of his knowledge, that Shake Shack is gone, but others have sprung up in the city.)

The rest of this lesson will address what the landscape can tell us, and presumes an active reading of the landscape. Note that while identifying the visual elements is an integral part of reading the landscape, an in-depth landscape analysis typically involves observation of individuals within the space, and often entails additional research to fully appreciate the history and social significance of the space.

NOTE:

Many of the examples that follow come from Kingston, New York, where Dr. Livecchi currently lives. We’re using these as examples in part due to ease of data collection (it’s easier to provide photos that display the relevant information), and in part because it affords a fair amount of diversity in its landscapes, and thus can provide a variety of examples.

Whose culture?

First and foremost, the cultural landscape gives us some indication of the dominant culture, as well as the economic circumstances of the place. For example, compare the images below.

is licensed under (CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication)

The architectural styles, signage, width of the streets, and infrastructure in these landscapes give us hints as to where they are. Although these landscapes may share some similarities, the visible qualities of each set them apart from one another. Even if we cannot readily identify the locations of these landscapes, we can be certain that they were produced within different cultural contexts. These images were chosen because they provide relatively clear indicators of location; it is important to remember that in some cases the differences may be small enough that they require close attention to detail — street lane markings, curb cuts, sidewalk and crosswalk design, and the (in)visibility of things like telephone or electrical lines are all indicators that observers often overlook because they are either meant to be overlooked or they are so familiar that we only passively recognize them.

All of these landscapes are situated in tourist areas of different cities. The differences in architecture, street design, and visible infrastructure (e.g., street lights, signage, bike racks, etc.) offer some idea as to where they were taken; they also suggest the histories of the places. The types of structures and decorative flourishes tell us that these are spaces where people either congregate or intend to spend money — and the condition of the structures indicates that someone (or several someones) has invested money into upkeep, presumably to maintain an inviting space that welcomes tourists.

Form follows function, sometimes

Second, the landscape can tell us something about the intended function of the space, and for whom the space is intended. For example, consider the landscapes in figures 6.12 and 6.13.

The landscape in figure 6.13 will be familiar to anyone who has visited a rural cemetery in the United States. Even without knowing the location, the language used on the stones, or the visual culture associated with the landscape in figure 6.12, even a casual observer would recognize it as a cemetery (despite the obvious differences with regard to density and groundcover). In both of these images, the kinds of features and their arrangement give us information as to these landscapes’ functions.

In some cases, function also entails some assumptions about for whom the landscape was designed. Figures 6.14 and 6.15 below provide two contrasting examples.

is licensed under (Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International).

is licensed under Attribution 2.0 Generic

These two landscapes physically express their intended functions and audiences. The playground is sized for children, and surrounded by apartment buildings. The red-light district relies on an established visual signal (red lights) to denote the availability of sex workers. Although the playground landscape is deserted, we would expect to see children playing. Adults without children might seem out of place and suspect. Likewise, the notable absence of children in the red-light district is in line with our expectations; their presence might be puzzling or concerning, as they might seem out of place.

As a corollary to this, elements on the landscape sometimes broadcast not only who is expected within them, but who is welcome within them. Consider, for example, the Old Dutch Church in Kingston, New York.

Even casual observers familiar with the United States will instantly recognize the building as a Christian church (and as an old church, given the presence of the churchyard and the stone and style of the headstones); we can surmise without real question that the space has a religious function and that members of some Christian denomination are welcome there. What stands out, however, is the flagpole, from which four flags fly: the American flag, a Black Lives Matter flag, a Pride flag, and a Transgender Pride flag. These symbols on the landscape are a visible means by which the church proclaims its identity as both American and as welcoming to members of social groups who have historically been marginalized.

Resistance

Third, landscapes can tell us a little about resistance to the local social order or to local conventions. Some activity leaves traces that indicate a use other than what was intended. For example, municipal officials may install benches in public spaces with the intent that people will sit on them — yet those same benches might also be used by homeless populations as somewhere to sleep. Likewise, skateboarders find particular joy in sliding across benches and low walls of concrete or granite. The presence of hostile or defensive architectural features such as spikes (figure 6.17), or less obvious features such as extra rails on benches (figure 6.18) visibly indicate the contested nature of some landscapes.

is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

is licensed under Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International.

What matters most?

Fourth, the landscape can tell us what is important to a particular community — both in terms of what a community claims is important in an official capacity, and in terms of resistance to that official line by smaller subgroups within that community. With regard to the former, things like monuments and street signs are visible, physical markers that reflect the values officially embraced by the community (discursively constructed or mediated by people in power). Choosing to commemorate individuals by naming or renaming streets after them is an established practice. Consider, for example, streets in cities with which you are familiar that were named for former political leaders such as presidents, governors, or mayors — or streets that are given secondary names to honor individuals, especially those fallen in combat. Later renaming of streets and alterations or removals of monuments can reflect cultural changes, as with the removal of Confederate monuments or the names of Confederate generals from military bases. Till (2004) captures this dovetailing of culture, politics, and space in the ways that landscapes are manipulated to political ends on both national and local scales.

It is perhaps easy to overlook street signs; we are accustomed to using them as references for navigation and to ignoring them at other times. Monuments, by contrast, are designed to stand out on the landscape. Their placement, size, and construction provide some indication of their importance to a given community. The Ulster County Courthouse in Kingston, New York (fig 6.19) provides an interesting example here.

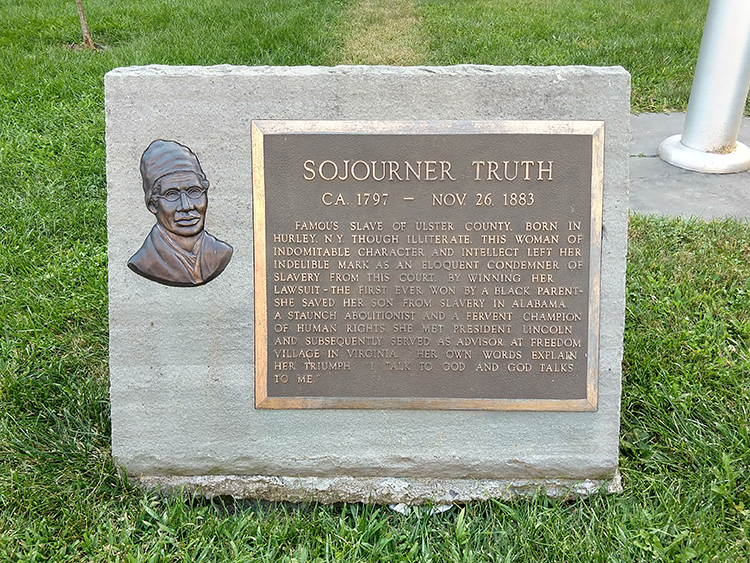

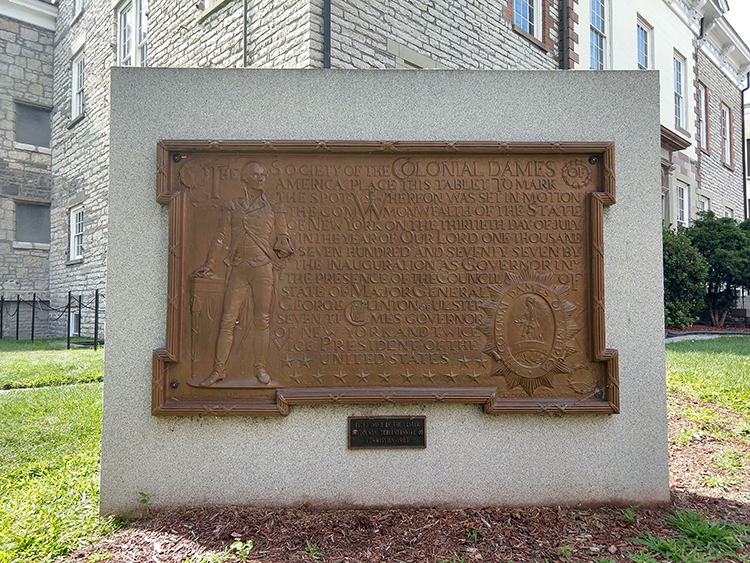

On the courthouse grounds stand two monuments. One of these (figure 6.20) is just visible just beyond the fence, near the base of the flagpole. The other (figure 6.21) stands just beyond the left edge of figure 6.19.

The text of this monument reads:

“SOJOURNER TRUTH

CA 1797 - NOV 26, 1883

FAMOUS SLAVE OF ULSTER COUNTY, BORN IN HURLEY, N.Y. THOUGH ILLITERATE, THIS WOMAN OF INDOMITABLE CHARACTER AND INTELLECT LEFT HER INDELIBLE MARK AS AN ELOQUENT CONDEMNER OF SLAVERY. FROM THIS COURT, BY WINNING HER LAWSUIT - THE FIRST EVER WON BY A BLACK PARENT - SHE SAVED HER SON FROM SLAVERY IN ALABAMA. A STAUNCH ABOLITIONIST AND A FERVENT CHAMPION OF HUMAN RIGHTS, SHE MET PRESIDENT LINCOLN AND SUBSEQUENTLY SERVED AS ADVISOR AT FREEDOM VILLAGE IN VIRGINIA. HER OWN WORDS EXPLAIN HER TRIUMPH: “I TALK TO GOD AND GOD TALKS TO ME.”

The text of this monument reads:

“THE SOCIETY OF THE COLONIAL DAMES OF AMERICA PLACE THIS TABLET TO MARK THE SPOT WHEREUPON WAS SET IN MOTION THE COMMONWEALTH OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK ON THE THIRTIETH DAY OF JULY IN THE YEAR OF OUR LORD ONE THOUSAND SEVEN HUNDRED AND SEVENTY SEVEN BY THE INAUGURATION AS GOVERNOR IN THE PRESENCE OF THE COUNCIL OF STATE OF MAJOR GENERAL GEORGE CLINTON OF ULSTER SEVEN TIMES GOVERNOR OF NEW YORK AND TWICE VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES.”

Both monuments stand on the grounds of this historic courthouse — one to commemorate the founding of the State of New York (relying on the image of President Washington to establish its connection to the nascent United States), and one to commemorate the legal success of a Black woman abolitionist from the region. Both commemorate events that took place here, and both events are significant to the region’s history — though for vastly different reasons. These elements on the landscape symbolically represent some value or idea that officials were trying to communicate publicly at the time the monuments were erected.

Landscapes with monuments such as these are often the sites of celebrations — and protests. Event organizers and speakers frequently make reference to the symbols visible in the landscape around them in order to appeal to the emotions of the onlookers, whether to instill a sense of pride or to inspire them to protest.

One final example will help illustrate this point. There is a park in Kingston, New York, called Academy Green. The park is a large triangle of grass bounded by Clinton Avenue, Albany Avenue, and Maiden Lane. This space is situated in a liminal part of Kingston, outside the historic Stockade District and on the edge of a residential neighborhood, with a major thoroughfare (Albany Avenue) defining its longest side.

On the green are three 11-foot-tall bronze statues on plinths, all of historic figures: Peter Stuyvesant (the director general of the New Netherland colony before it was given to the British in the mid-17th century), George Clinton (first governor of New York State, and still not the funk musician), and Henry Hudson (English explorer who navigated up what is now the Hudson River). Cast in 1898, the statues were initially part of a set adorning a bank building in New York City, and were rescued from a junkyard by an individual in 1943, who donated them to Ulster County (Schwarz, 2018).

The park generally functions during the day as a space of socialization for adults within Kingston’s Black community. Given its visibility along Albany Avenue and its position relative to other neighborhoods, it also serves as one of several active sites of protest within Kingston. In 2020 and 2021, the park has seen nonviolent protests against police brutality (particularly in the wake of George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis), hosted weekly walks for Black lives, and has served as the rallying point for a protest and march against the sale of Chiz’s Heart Street — a large group home for mentally ill people — to a wealthy hotel developer (a common theme; Kingston is experiencing a wave of pandemic-enhanced gentrification as affluent New Yorkers leave Manhattan and Brooklyn for the Mid-Hudson Valley).

In 2020, Kingston-based community organizer Frances Cathryn began a project to point out the historically racist actions of the figures commemorated by the statues in the park. In an op-ed piece, she notes that there is an inherent irony as “local activists of color and young Black students gather at Academy Green and call for the acknowledgment of their basic civil rights in front of an enslaver” (Cathryn, 2020). Yet perhaps it’s not an innocent irony: event organizers or participants who are aware of the landscape might use those features as references to stir up stronger emotions among participants.

Landscape is not something that simply exists in the background. An understanding of the landscape can enable individuals and groups to deploy symbolically across a wide range of readings, and to make a variety of different public statements.

Read/Listen:

Davis, C. and Mars, R. (2018, August 14). It’s Chinatown. 99% Invisible. Podcast audio. [listen to the first story; 23 minutes]

Recommended:

Norton, A. and Mars, R. (2013, January 23). In and out of LOVE. 99% Invisible. Podcast audio.

Schein, R. (1997). The place of landscape: A conceptual framework for interpreting an American scene. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 87(4), 660-680.

Stilgoe, J. (1998). Outside lies magic. Walker and Company.

Additional References:

Bellentani, F. (2016). Landscape as text. In C. J. Rodrigues Higuera and T. J. Bennett (Eds.), Concepts for semiotics (pp. 76-87). University of Tartu Press.

Cathryn, F. (2020). The Kingston Monument Project: A community organizer on replacing the monuments in our public spaces. Chronogram.

Duncan, J. and Duncan, N. (1988). (Re)reading the landscape. Environment & Planning D: Society and Space, 6(2), 117-126.

Schwarz, A. (2018, September 12). An appreciation of Academy Green’s statues. Hudson Valley One.

Till, K. (2004). Political landscapes. In J. S. Duncan, N. C. Johnson, and R. H. Schein (Eds.), A companion to cultural geography (pp. 347-364). Blackwell.